The Monitor Story

An overview of the development and career of USS Monitor from conception by John Ericsson, through a short career as a warship of the United States Navy, to its loss off Cape Hatteras, NC, in December 1862, and its subsequent discovery and recovery.

On March 9, 1862, the Civil War battle of Hampton Roads between the ironclads USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (formerly USS Merrimack) heralded the beginning of a new era in naval warfare. Though indecisive, the battle marked the change from wood and sail to iron and steam.

Today, the remains of USS Monitor rest on the ocean floor off North Carolina’s Outer Banks, where the ship sank in a storm on December 31, 1862. Discovered in 1973, Monitor’s wreck site was designated as the nation’s first national marine sanctuary in 1975. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) manages the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary (MNMS). The sanctuary’s purpose is to preserve this iconic vessel’s historical record and interpret its role in shaping US naval history.

Creating Monitor

The efforts by the Confederates to construct an ironclad in Hampton Roads were well known to the federal authorities. Throughout the summer of 1861, newspaper reporters and the general public visited the Gosport Navy Yard to observe the work on Virginia. Newspapers throughout the South carried regular updates on the progress of the conversion of the former hull of USS Merrimack to an ironclad warship. Northern papers reported similar stories. As the work proceeded, it became evident to the North that if the Confederacy succeeded in launching an armored vessel, there was not a Union ship that could equally challenge it.

The need to offset this potential Confederate naval superiority moved the United States Navy Department to appoint an Ironclad Board of naval officers to seek and evaluate plans for the construction of ironclad vessels for federal service. On August 3, 1861, Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles published an announcement calling designers to submit plans for ironclad warships to the Navy Department. This was not the first time that the United States had toyed with the idea of building ironclads. Since the late 1840s, the Navy had considered plans for designing and testing ironclad vessels. In 1842, Robert L. Stevens won a contract to construct a floating iron battery for the Navy. However, the ‘Stevens battery’ was never completed.

The first successful launching of ironclad vessels for United States service occurred during the summer of 1861, not under the direction of the Navy but rather the US Army Quartermaster Corps. The War Department ordered the building of ironclad gunboats on the Mississippi under the direction of Samuel Pook and James Eads. These ironclad river steamers known as “Pook Turtles” or “Eads’ Gunboats” would be used throughout the war on the western rivers. Still, the command of the Union Navy remained conservative and cautious in approaching iron shipbuilding.

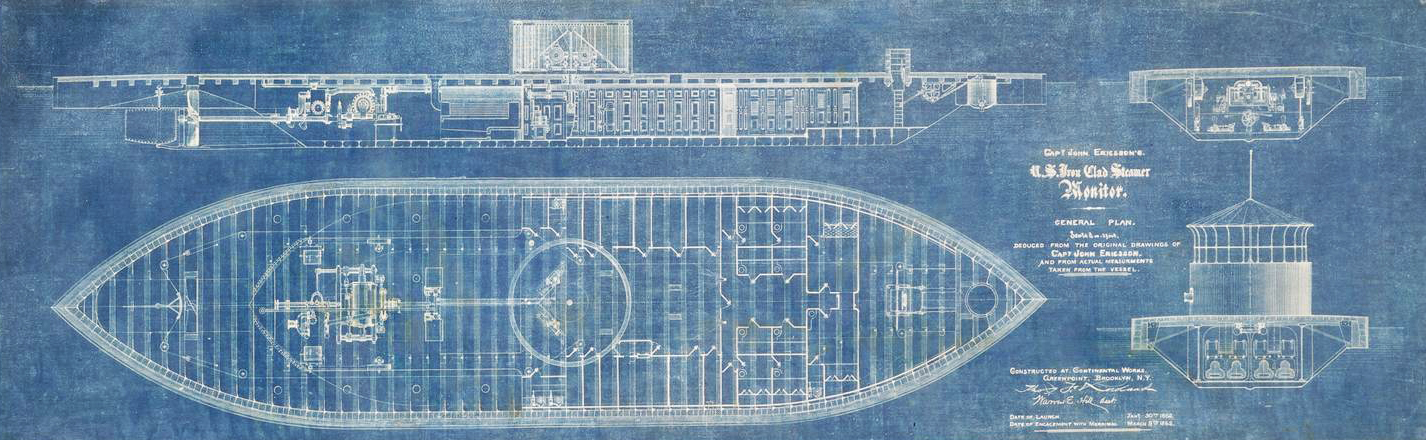

Following Welles’s call for plans, several designers presented proposals to the Ironclad Board for consideration. Among them was Cornelius Bushnell, who controlled several railroads in Connecticut and ventured to enter the world of naval architecture. With the help of naval constructor Samuel Pook, Bushnell developed a plan for an ironclad steamer, to be called Galena, a conventional vessel with armor constructed of iron bars laying over iron rails. To verify the seaworthiness of his ship, Bushnell sought out the advice of the renowned engineer John Ericsson. According to Bushnell, after Ericsson had confirmed that Galena’s design was sound, Ericsson produced a model of an “impregnable iron battery” that he had proposed to French Emperor Napoleon III in 1854. The model showed a ship with an almost submerged hull and a single revolving turret fixed to the deck, containing a single cannon. Though Napoleon had not accepted the plan, Ericsson emphasized to Bushnell that the battery’s design was viable and that the ship could be built quickly.

Bushnell was so impressed with Ericsson’s model that he took it to Secretary Welles, who agreed that the design had “extraordinary and valuable features” and it should be submitted to the Ironclad Board for consideration. Bushnell presented Ericsson’s model to the Board, but it was rejected as too outlandish. Bushnell then persuaded Ericsson himself to appear before the Board to defend the design.

Ericsson’s defense of his design was successful. When the Ironclad Board submitted its final report to Secretary Welles, Ericsson’s was one of three designs recommended for approval. The contract offered to Ericsson was for $275,000, but it stipulated that the ship must be completed in one hundred days and that it must prove successful in every stipulation outlined in the contract, or payment would be withheld.

Monitor Artifacts

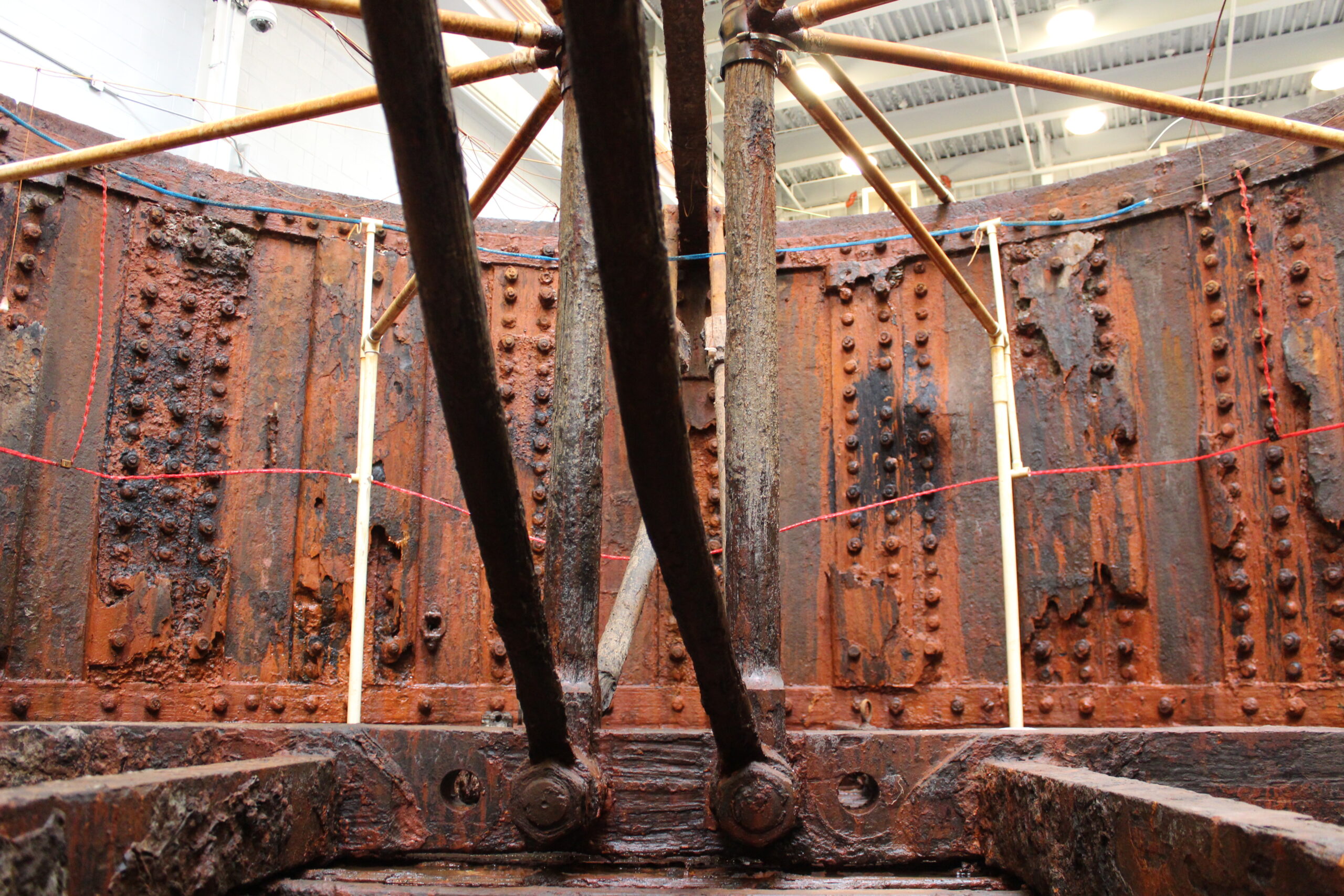

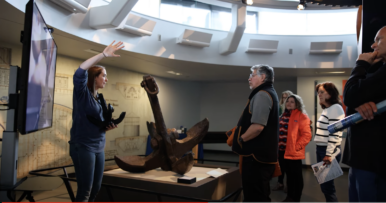

When the sea claimed USS Monitor in 1862, the world lost an irreplaceable piece of cultural heritage. Fortunately, 140 years later, one-fifth of the ship was recovered from the depths of the Atlantic. These one-of-a-kind artifacts now reside within the Batten Conservation Complex. View these items in our Museum catalog.

The Battle of Hampton Roads

The Mariners’ Museum 1945.0427.000001

In early March 1862, construction crews in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, New York, and Portsmouth, Virginia, were rushing to complete two vessels of radically different designs. In Greenpoint, the Union ironclad Monitor was completing its sea trials before heading south to Hampton Roads to counter the threat of the Confederate ironclad Virginia (formerly Merrimack). Virginia‘s first mission was to break the Union blockade of Hampton Roads and protect the waterways to Richmond from Union advances. Yet Stephen Russell Mallory, secretary of the Confederate Navy, had even grander plans for the ironclad. He hoped that Virginia could then continue onward to ravage the coastal cities of the Union. Washington, D.C., New York, and Boston were desired targets. In contrast, Monitor’s mission was very focused: destroy Virginia at its moorings if possible, but more importantly, protect the fleet at Hampton Roads and the District of Columbia from attack by the “rebel monster.”

Both ironclads achieved certain elements of their objectives. Virginia destroyed key Union vessels in Hampton Roads and kept the James River closed to Union advances for a time. Monitor saved the fleet from further destruction and kept Virginia trapped in Hampton Roads. However, the significance of March 8-9, 1862, went far beyond the immediate needs in Hampton Roads. Virginia demonstrated the power of iron over wood on March 8, and both Monitor and Virginia showed the world’s navies the future of warship construction when the two clashed on March 9. This first meeting of two ironclad warships in battle forever changed naval architecture, battle tactics, and the very psychology of the men who served within them.

Saturday, March 8, 1862, was laundry day for the crews of the Union’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron in Hampton Roads, Virginia. The rigging of the wooden vessels was festooned with blue and white clothing, drying in the late winter sun. Shortly after noon, the quartermaster of USS Congress, which was anchored off Newport News Point, saw something strange through his telescope. He turned to the ship’s surgeon and said, “I wish you would take the glass and have a look over there, Sir. I believe that thing is a’comin’ down at last.”

That “thing” was CSS Virginia. The Confederates had been converting the burnt-out hull of the steam screw frigate USS Merrimack into a casemated ironclad ram at Gosport Navy Yard on the Elizabeth River. It had taken nine months for the conversion, and Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan was impatient to strike at the blockading fleet. March 8, 1862, would be Virginia’s sea trial, as well as its trial by fire.

The men of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, had grown weary of waiting for Virginia to come out. They now scrambled to prepare for battle. In the panic of the moment and with the tide at ebb, several vessels ran aground, including USS Congress and USS Minnesota.

USS Cumberland was Buchanan’s first target. With his guns firing at the wooden ship, Buchanan rammed Cumberland on the starboard side. The hole below its waterline was large, and the ship immediately began to sink, nearly taking down Virginia. Scores of Union sailors from Cumberland died at their guns or went down with their ship. Guns were still firing and flags still defiantly flying.

Virginia broke free and steamed slowly into the James River. The men on the stranded Congress began to cheer, thinking they had been spared the same horrific fate. However, that cheer was cut short when they saw that Virginia had made a ponderous turn.

Virginia’s withering firepower tore into USS Congress for nearly two hours. With most of the crew dead or wounded, including the commanding officer Lieutenant Joseph B. Smith., the remaining men of Congress surrendered. Enraged at Union shore batteries which continued to fire upon the white flag, Buchanan ordered Congress to be set afire and then he began firing back at the shore with a rifle. He quickly became a target on Virginia’s exposed top deck. Wounded, he turned command over to his Executive Officer, Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones, who returned Virginia to its moorings that evening. Falling darkness of evening and a receding tide had saved the steam frigate USS Minnesota from the same fate as Congress and Cumberland.

The mood in Hampton Roads was one of disbelief and, for some, resignation. The hope of the Union Navy — USS Monitor — had arrived too late to sink Virginia at its moorings. Monitor, a radical vessel designed by Swedish-American genius John Ericsson, had been built in just a little over one hundred days, thanks to the combined muscle of the Northern iron industry. Launched in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, this strange little ship had only two guns — XI-inch Dahlgrens — housed in its most distinctive feature: a revolving gun turret that sat upon a flat deck. Commanded by Lieutenant John Lorimer Worden, Monitor and crew had left New York bound for Hampton Roads on March 6, 1862. A storm very nearly sank the vessel before they arrived at their destination on the evening of March 8.

The distant sound of booming guns greeted Monitor as it approached the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Nearing Fortress Monroe as darkness fell, Monitor’s Acting Paymaster, William Keeler, recalled that as Monitor drew closer to the scene, civilian vessels “were leaving like a covey of frightened quails & their lights danced over the water in all directions.”

Worden immediately received orders to protect the grounded Minnesota, still trapped on Hampton Flats. The burning Congress provided an eerie backdrop to the fevered activities in Hampton Roads, along with the “considerable noise” floating across the water from Confederate celebrations at Sewell’s Point. Union crews struggled in vain to tow Minnesota to safety. Exploding munitions from Congress pelted Minnesota throughout the evening.

After midnight, the flames of Congress reached the ship’s powder magazine and the whole of Hampton Roads was treated to a horrific fireworks display. Despite being more than two miles from the dying vessel, the explosion was so intense it “seemed almost to lift us out of the water,” William Keeler wrote. The blast was felt for miles around.

Just after dawn on March 9, the men of Virginia had a hearty breakfast made all the more festive by two jiggers of whiskey for each man. In contrast, Monitor’s exhausted crew sat together on the berth deck eating hardtack and canned roast beef, washing it down with coffee. Many of them had been awake for well over 24 hours.

Intense fog early that morning delayed Virginia‘s assault upon the stranded Minnesota, so it was not until 8 a.m. that Virginia was able to approach its prey. Virginia‘s crew saw what appeared to be “a shingle floating in the water, with a gigantic cheesebox rising from its center,” sitting alongside the frigate. Confederates following Northern newspapers’ reports knew that this “cheesebox” must be the anticipated Union ironclad. Virginia‘s first shot went through Minnesota’s rigging shortly before 8:30 a.m., while Monitor’s crew braced for battle inside their untested, experimental vessel.

Worden moved Monitor directly toward Virginia, placing his ship between Virginia and its prey. Within yards of Virginia, Worden called ‘all stop’ to the engines and sent the command to the crew in the turret : “Commence firing!” The “cheesebox” had found its voice.

A “rattling broadside” could have easily come from Minnesota as Virginia soon slammed into the turret. The gunners quickly realized that both they and the turret were unharmed. They also found that while the turret turned well, it proved difficult to stop revolving once in motion. Eventually, they let it continue to revolve, firing “on the fly” when the enemy target came in sight.

The conventions applied to traditional naval tactics soon went by the wayside. Though the men had carefully marked the stationary portion of the deck beneath the turret with chalk marks to indicate starboard and port bearings and bow and stern, the marks were soon obliterated by sweat, falling from the gunners “like rain.” Worden, stationary in the pilothouse, continued to give commands in the traditional way. When asked, “How does the Merrimac bear?”, Worden’s reply, “on the starboard beam”, was of little use to the turret crew.

For more than four hours, both vessels circled, testing each other’s armor and looking for vulnerabilities. Finally, just after noon, Virginia‘s rifled stern gun fired directly into Monitor’s pilothouse at a range of 10 yards, just as Worden was peering out. Stunned and temporarily blinded, Worden gave the order to “shear off” temporarily. He turned command over to his Executive Officer, Samuel Dana Greene, and told his officers, “to [s]ave the Minnesota if you can.” Returning to the damaged pilothouse, Greene observed that Virginia appeared to be in retreat and abandoned the chase to protect Minnesota. On Virginia, Catesby Jones interpreted Greene’s action as retreat and believed Monitor had broken off from the fight. With the tide receding, Jones made a course for Gosport to repair his vessel’s damage.

Both sides claimed victory.

Though the March 9 battle was largely uneventful, the long-term effect of the action was significant. Monitor’s timely arrival on the evening of March 8 ensured that Virginia would be unable to break the blockade in Hampton Roads. Monitor saved Minnesota outright, so much so that one Minnesota crew member had his tombstone designed to look like Monitor. An honor to the ship that saved his life, and helped keep Virginia forever trapped in Hampton Roads until the Confederate vessel was destroyed by her crew on May 11, 1862. An event that followed the surrender of Norfolk to Union forces.

The long-term impact of the battle was more profound, domestically and internationally. Both Monitor and Virginia served as prototypes for classes of vessels that drew upon their innovative designs. The ironclad rams of the Confederacy and the turreted monitors of the Union saw action in the Atlantic, Gulf, and Western rivers. The monitor design continued as the principal coastal and riverine warship in North and South America, Europe, and Russia until the turn of the century. While ironclads had certainly existed before Monitor and Virginia, their meeting on March 9, 1862, ushered in the next phase of naval warfare, where machine and armament become paramount, and the graceful wooden sailing ships of the age of fighting sail became forlorn relics of the past.

The author Herman Melville summed it up rather gloomily in part of his poem “A Utilitarian View of The Monitor’s Fight” published in 1866:

Yet this was battle, and intense —

Beyond the strife of fleets heroic;

Deadlier, closer, calm ‘mid storm;

No passion; all went on by crank,

Pivot, and screw,

And calculations of caloric.

Melville ends with the pronouncement, “War shall yet be, but warriors/Are now but operatives….”

In this way, the first battle of ironclads marked a shift in warfare that would be manifested in ship design, battle tactics, and the very psychology of the men involved. “There isn’t enough danger to give us glory,” lamented William Keeler, paymaster of USS Monitor, to his wife Anna. A Confederate officer of a later ironclad simply said, “the poetry of the profession is gone.” Life in the ironclad age would be very different indeed.

USS Monitor Conservation

The USS Monitor project is just one part of the Cultural Heritage Conservation efforts taking place at The Mariners’. More than 200 tons of archaeological material was recovered from the wreck of USS Monitor.