Well…probably not the kind of Amazons you’re thinking about, these were the Amazon-class steam screw sloop’s HMS Daphne, Dryad and Nymph of the Royal Navy and the “hunt” occurred off the East Coast of Africa as they worked to suppress the African slave trade.

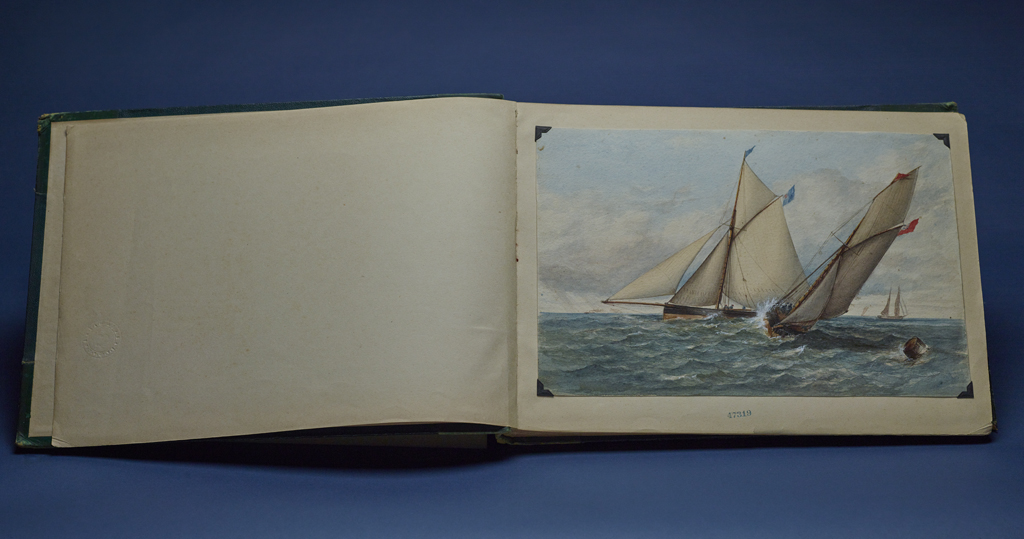

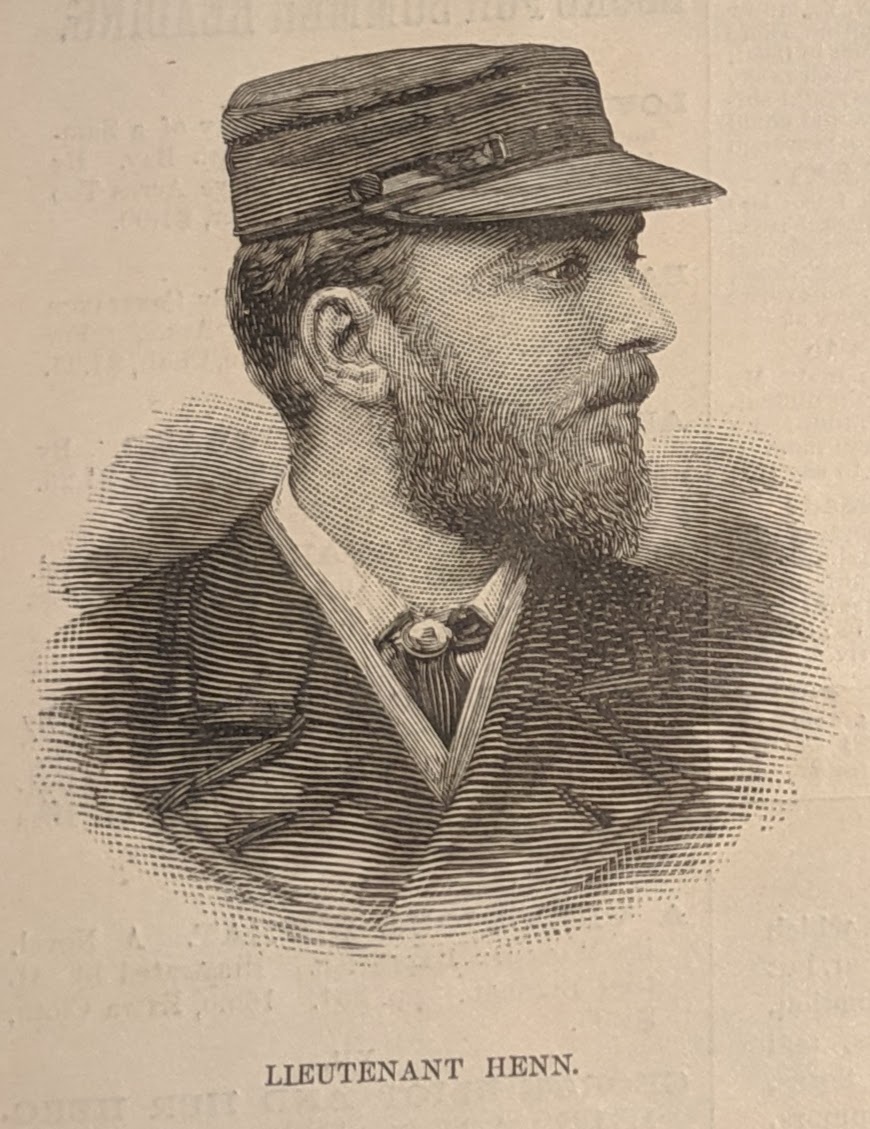

I became interested in this story after the library transferred an album of watercolors and sketches over to the object collection (which is where works of art normally live). The album contained thirty-seven images created by Lt. William Henn of the Royal Navy. For you America’s Cup fans that name should sound familiar. Henn and his wife Susan and their pet Maltese monkey, Peggy, raced their 90-ton cutter yacht Galatea (which was also their house!) against Mayflower in the 1886 America’s Cup.

Accessioning the images has taken me about eight months because the work presented several big challenges. First, the images had been scrambled and placed in random order in the album. Luckily, they weren’t glued down so I was able to remove them–but getting them into the right order has NOT been a walk in the park! Not all the works are dated or identified, and the majority are related to Henn’s career in the Royal Navy–something I didn’t know anything about. It’s also obvious that I am only looking at a small fragment of Henn’s original output. After some seriously extensive research to reconstruct Henn’s career, I have finally reached the point where I can reorder the artworks—or at least get really, really close–and the story the images tell is fascinating!

William Henn was born in Dublin in 1847. At the age of thirteen he entered the Royal Navy as a naval cadet aboard HMS Trafalgar. Between 1862 and 1866 Henn was stationed aboard HMS Galatea. He must have enjoyed his time aboard her because he named the yacht he sailed in the America’s Cup after her! During the Civil War, Galatea sailed throughout the Gulf of Mexico and along the East Coast of the temporarily un-United States. The ship even made a visit to the Chesapeake Bay in January of 1865. Other interesting events in Henn’s career included a stint with one of the Royal Navy ships that helped lay the transatlantic cable in 1866 and in 1872 he was second in command of the Royal Geographical Society’s expedition to find the missing Dr. David Livingston.

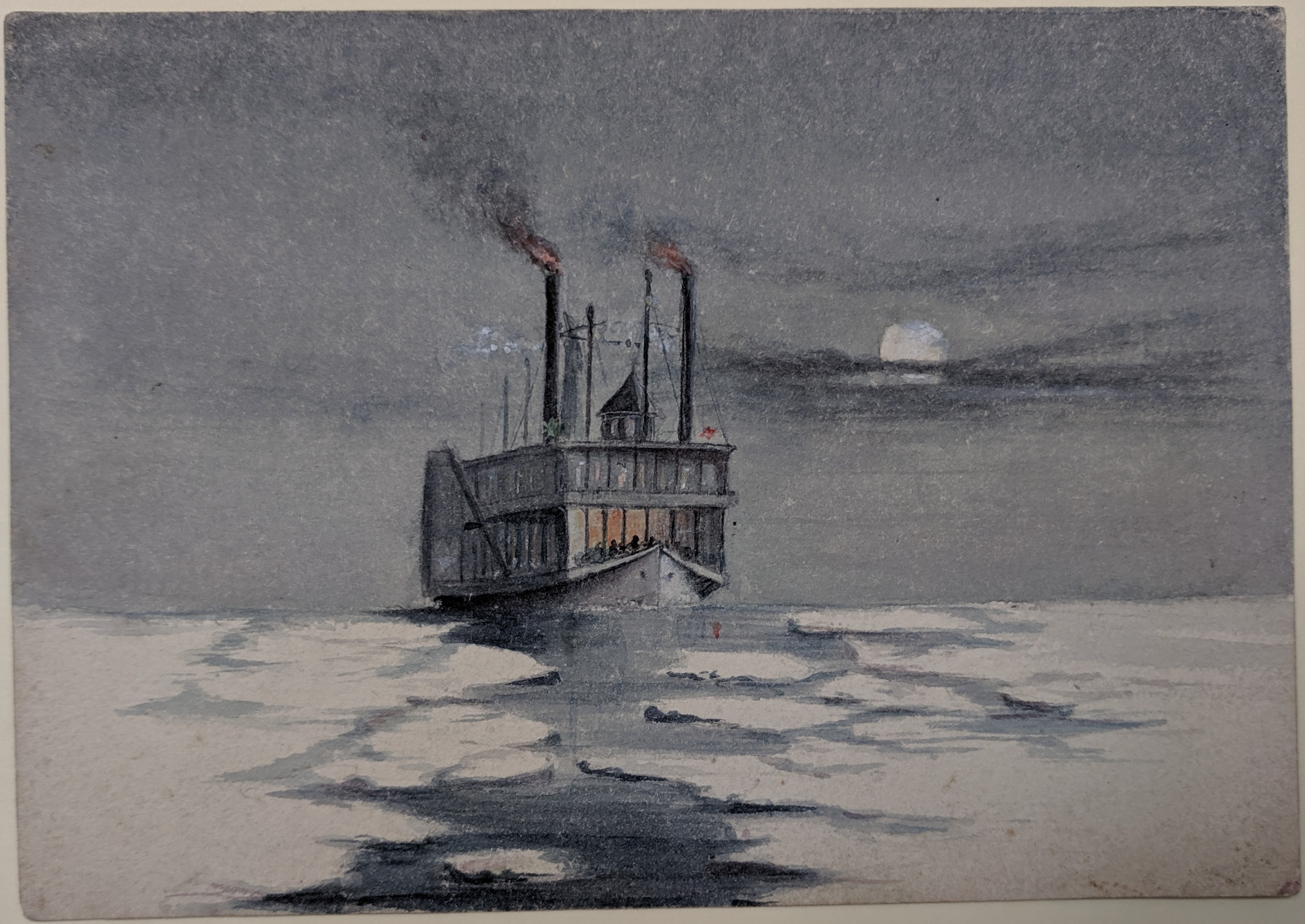

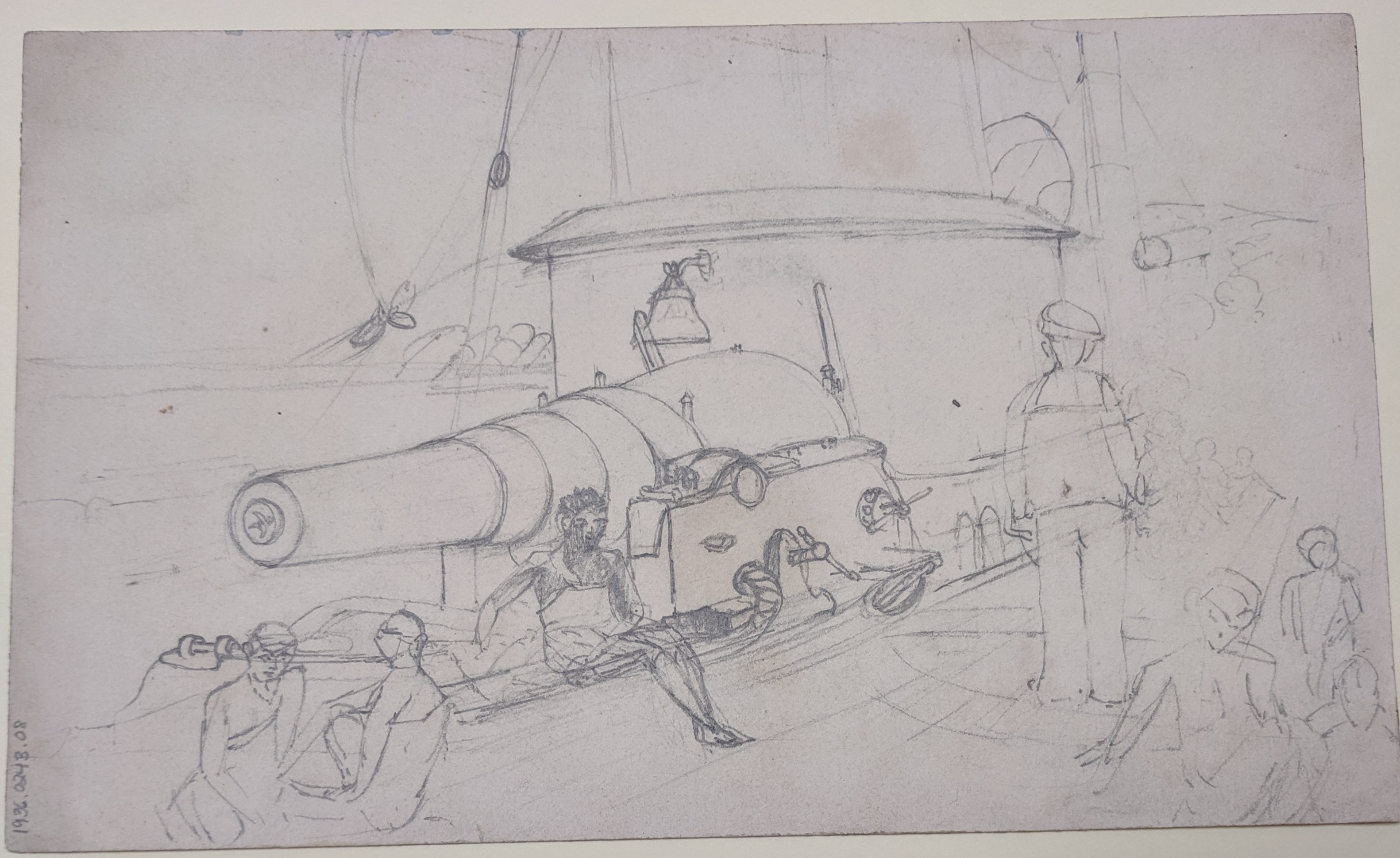

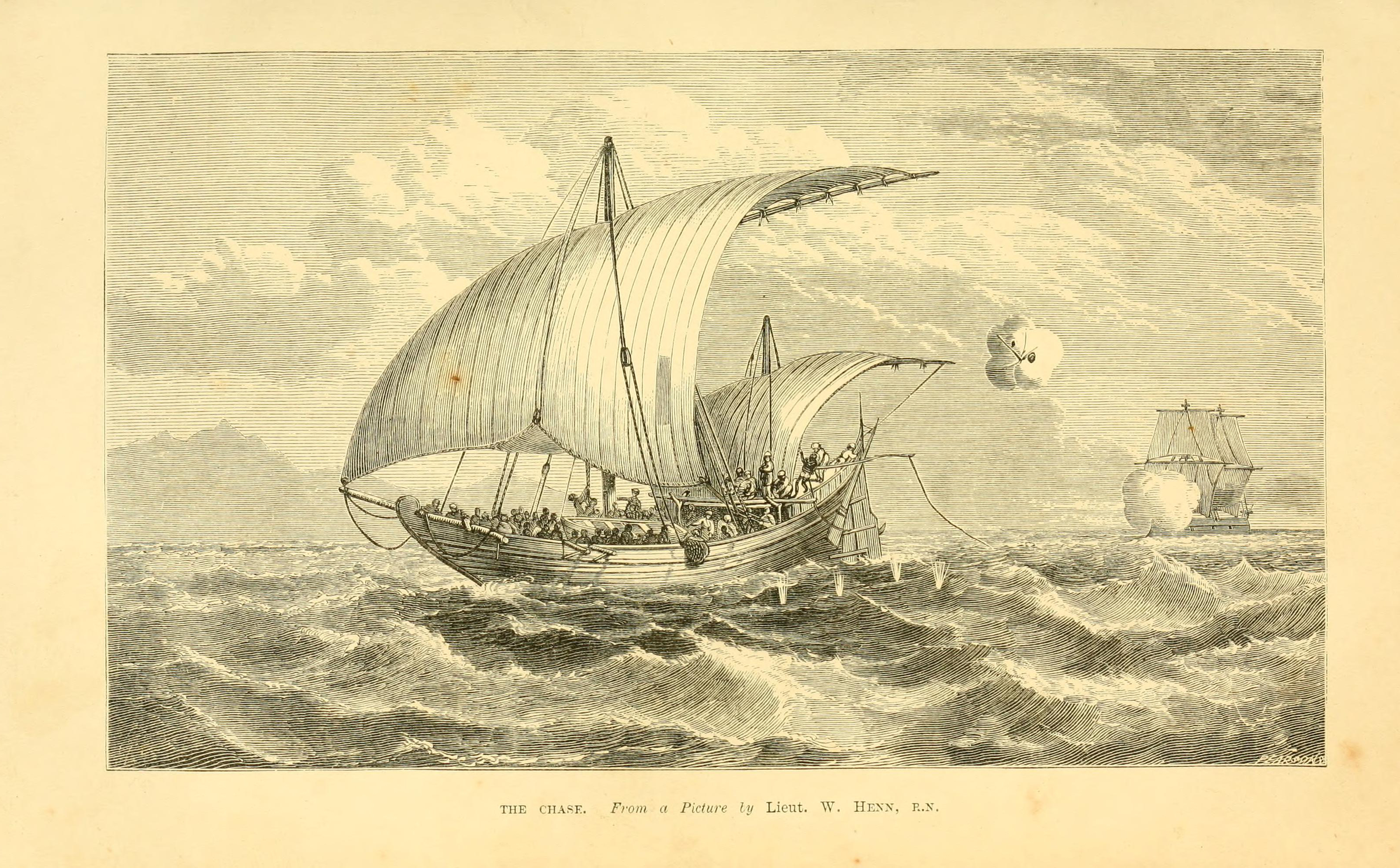

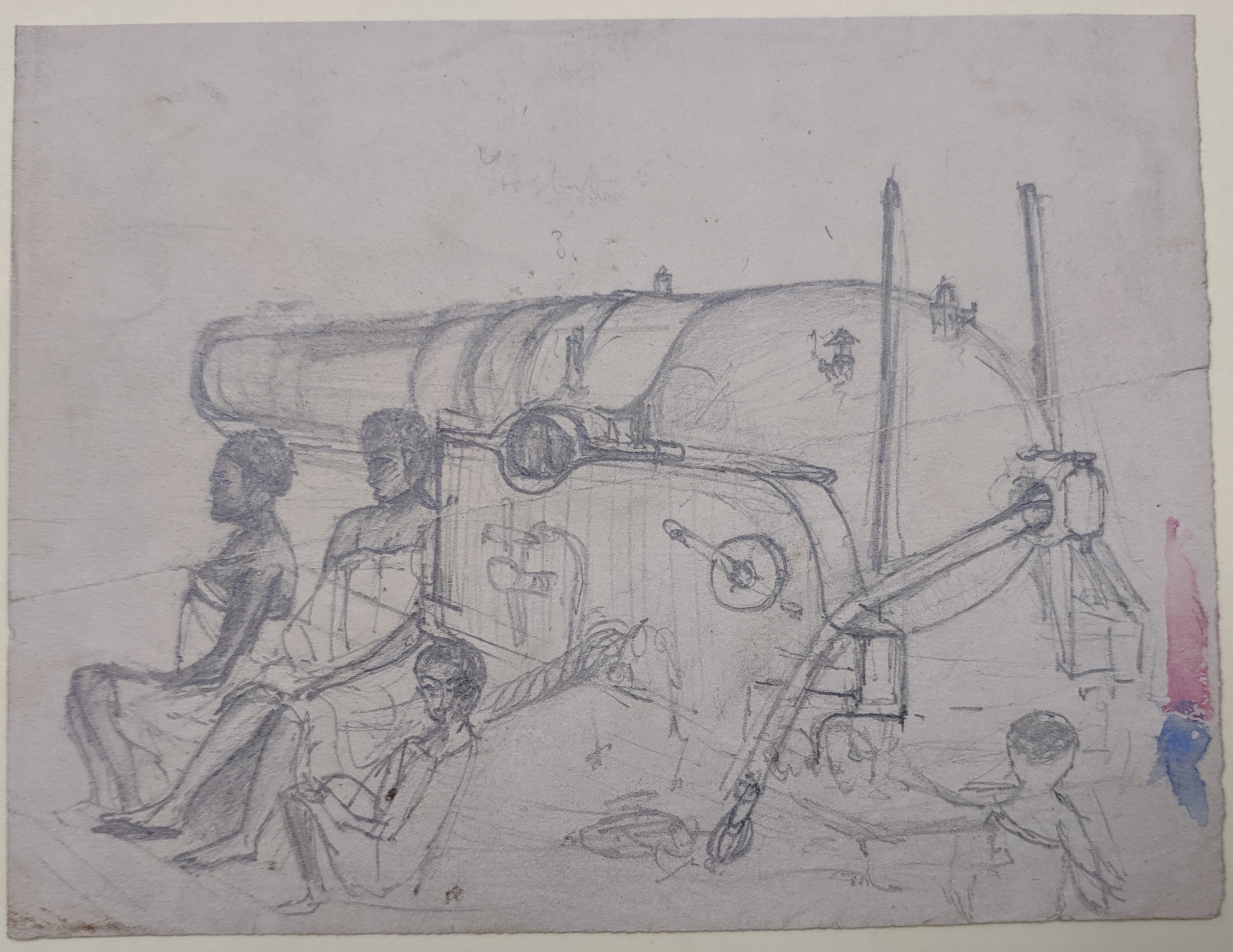

By August 1, 1867 Henn was a sub-Lieutenant stationed aboard HMS Daphne. This ship, along with her sister ships HMS Dryad and HMS Nymphe, were part of the Royal Navy’s new Amazon class. These new steam screw sloops carried square sails on their forward masts while the rearmost, or mizzenmast, carried a triangular sail. This sail arrangement meant they were particularly well-suited for operations in the waters off east Africa where sailing routes were ruled by the monsoon. With the capacity to efficiently steam and sail in the monsoon winds, Daphne and her sisters became Britain’s most formidable weapons in the fight against the slave trade in east Africa.

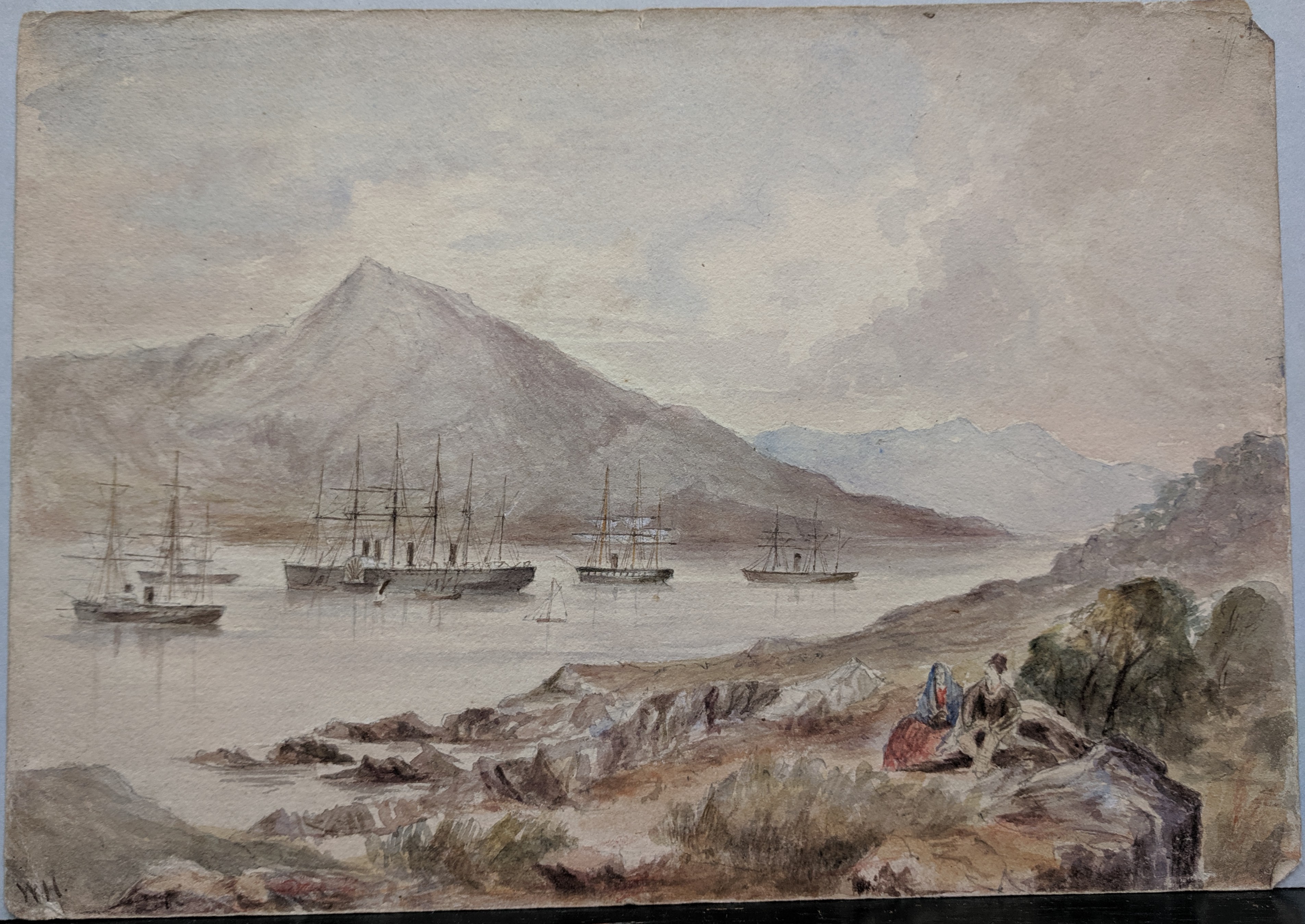

Their “hunt” was organized by Leopold Heath, commodore of the East Indies Station in Bombay. For quite some time, Heath had been developing a plan to stage his ships at natural choke points along the coast where their barque rigs and engines allowed them to maneuver against the prevailing monsoon winds and pounce upon unsuspecting slave trading dhows sailing along the shore.

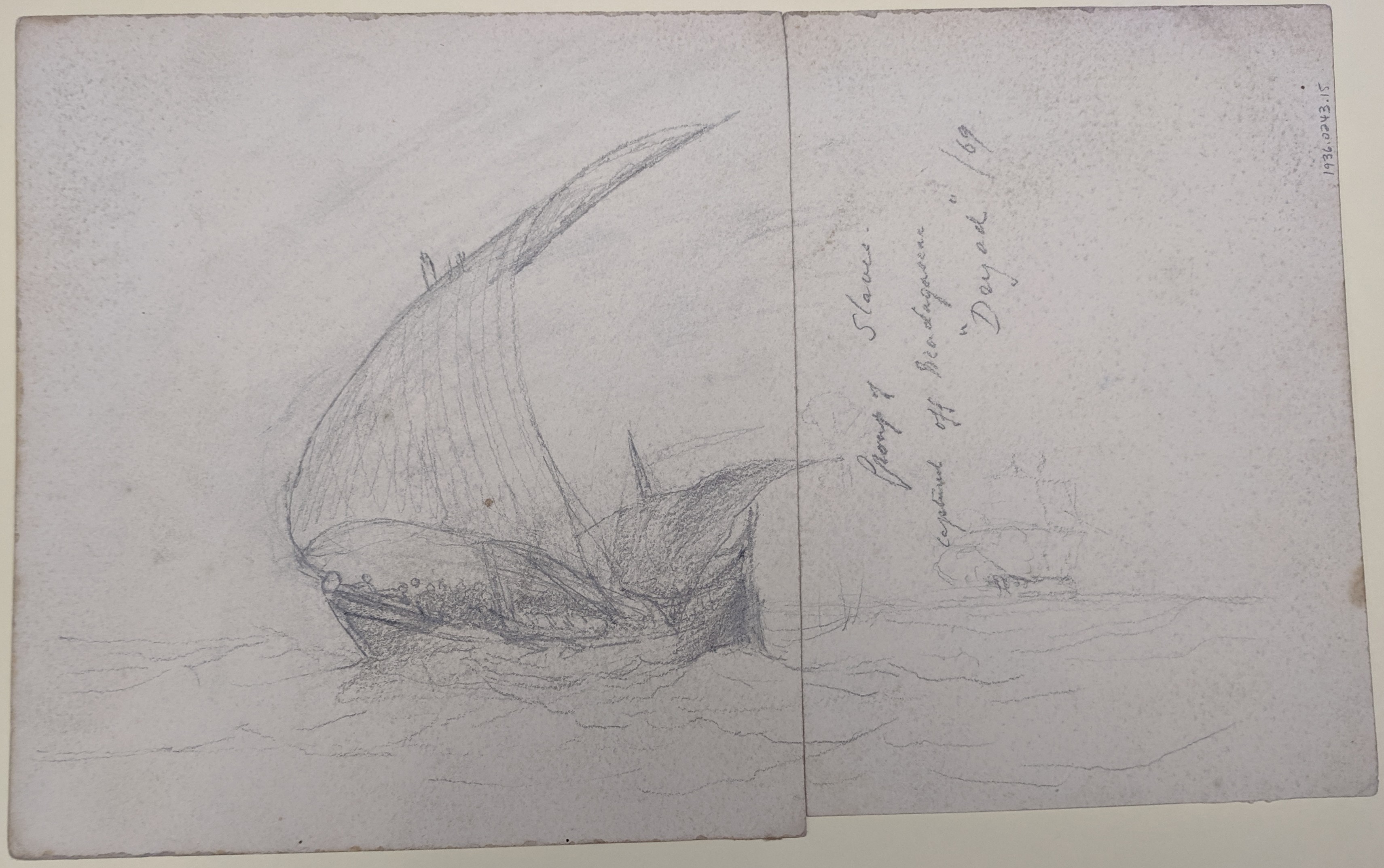

Daphne was the first Amazon Heath placed in action and by mid-September 1868 she and her crew were sailing between Zanzibar and Bombay actively sighting, stopping, searching and seizing dhows found to be carrying slaves. Heath’s tactic was obviously effective because slave traders desperate to evade capture began employing a particularly heinous method of escape. During a chase on October 28th, when the crew of a cornered dhow became desperate they ran their vessel through the breakers and onto the beach. Within just a few moments the dhow broke apart in the pounding surf. Daphne’s crew immediately sent a boat to save as many lives as possible. Sadly, once they reached shore it was too late for many of those trapped within the vessel or too weak to haul themselves ashore. The crew were able to save seven children, all around six years old, who had been unable to leave the wreck due to extreme weakness. Several were paralyzed in a fetal position from being packed between the vessel’s frames.

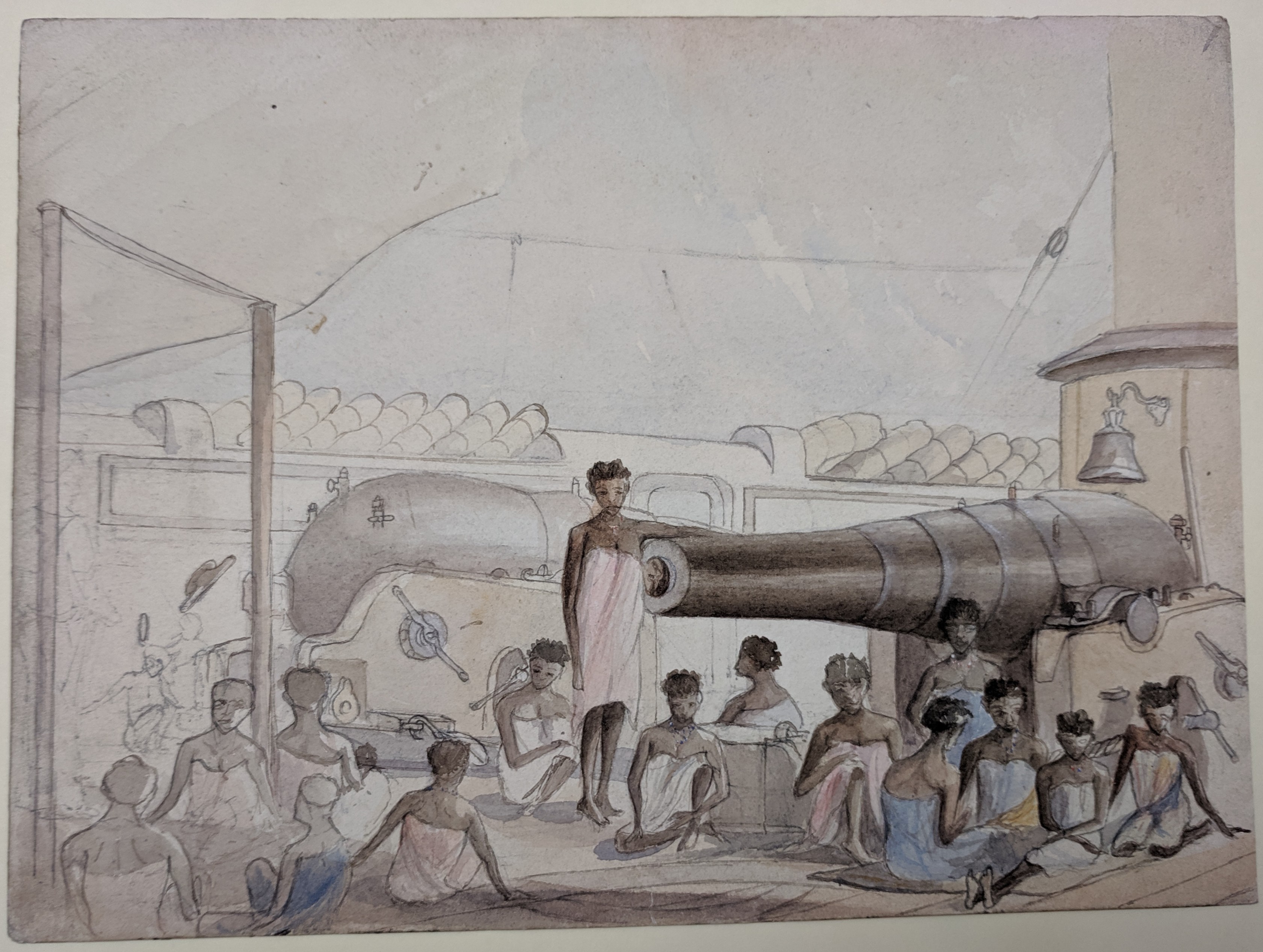

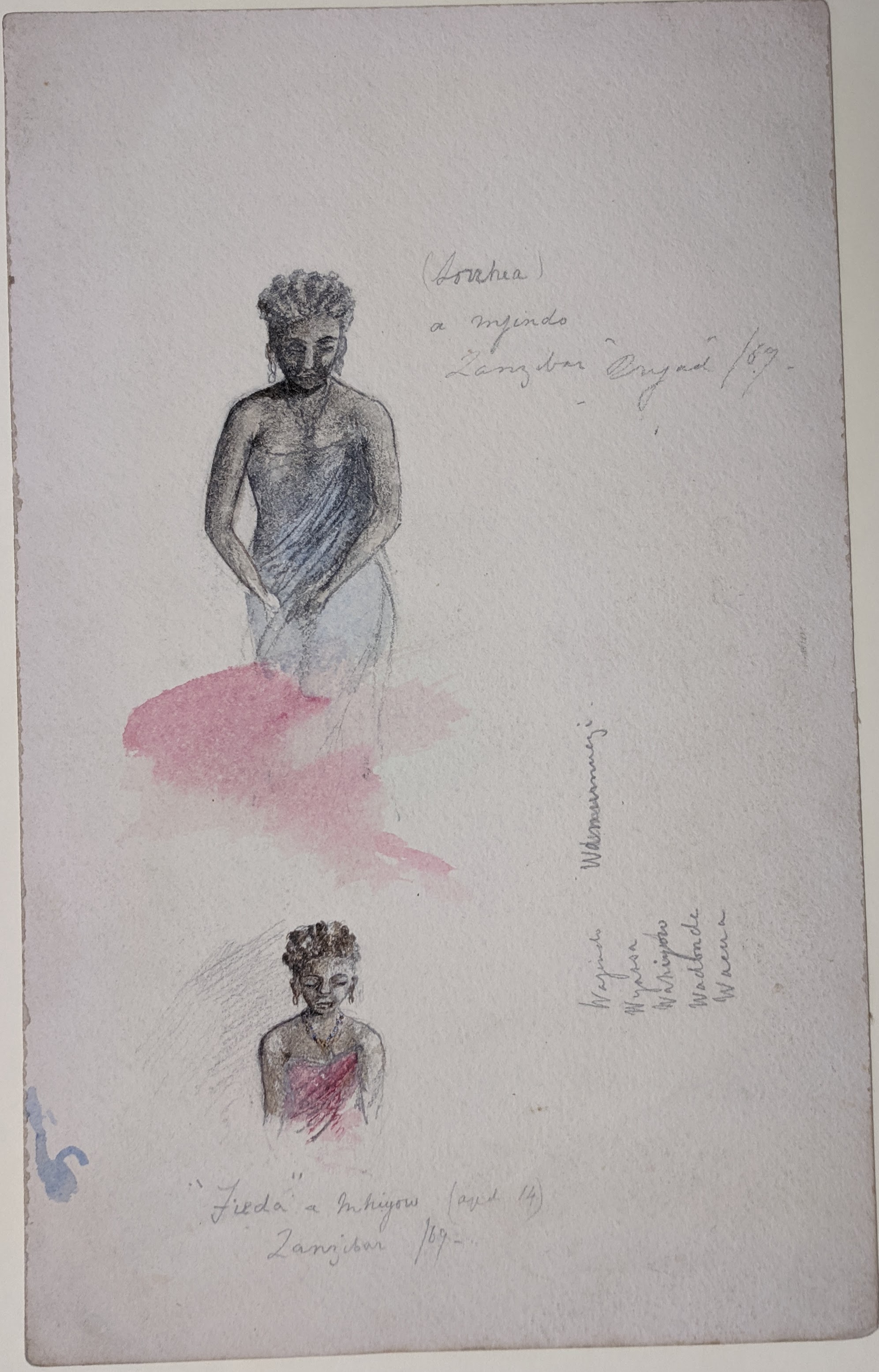

As Daphne continued her hunt, Lt. Henn was placed in charge of one of the ship’s cutters and tasked with intercepting dhows off the coast of Brava. On November 1st, Daphne observed Lt. Henn chasing and capturing a dhow. When the vessel was brought alongside it was discovered to be crammed with 156 men, women, and children. Daphne’s captain, George Sulivan, wrote “the deplorable condition of some of these poor wretches, crammed into a small dhow, surpasses all description; on the bottom of the dhow was a pile of stones as ballast, and on these stones, without even a mat, were twenty-three women huddled together—one or two with infants in their arms—these women were literally doubled up, there being no room to sit erect; on a bamboo deck, about three feet above the keel, were forty-eight men, crowded together in the same way, and on another deck above this were fifty-three children. Some of the slaves were in the last stages of starvation and dysentery.”

Before long, Daphne had intercepted so many dhows the crew found themselves struggling to take care of 322 liberated slaves. After a difficult voyage, the ship managed to reach the Seychelles, but not before an outbreak of smallpox had occurred. They landed their living cargo on the Quarantine Island and set about building a structure large enough to house everyone before heading to Bombay. Unfortunately, when they returned four months later they discovered that more than fifty of the former captives had died from the disease.

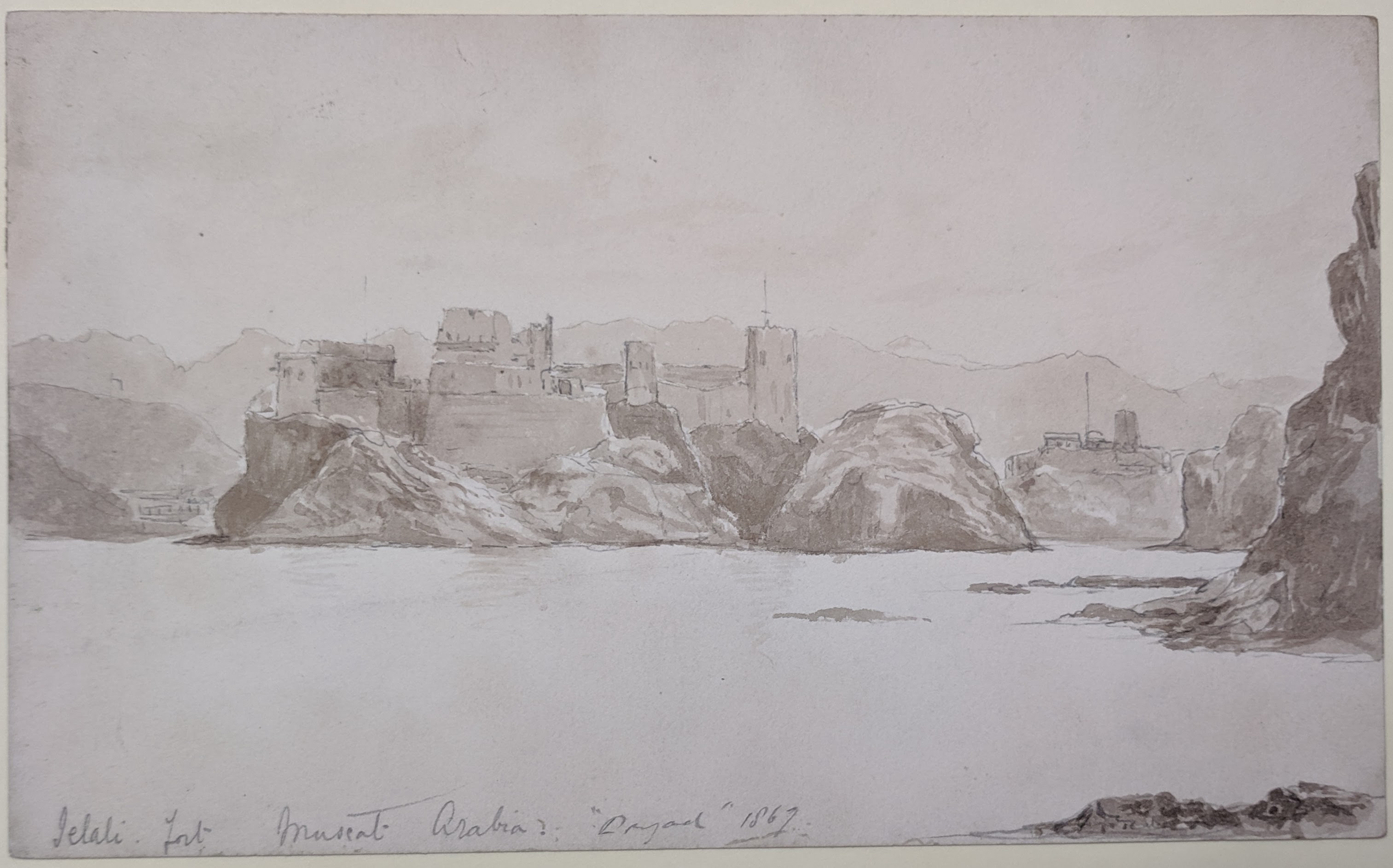

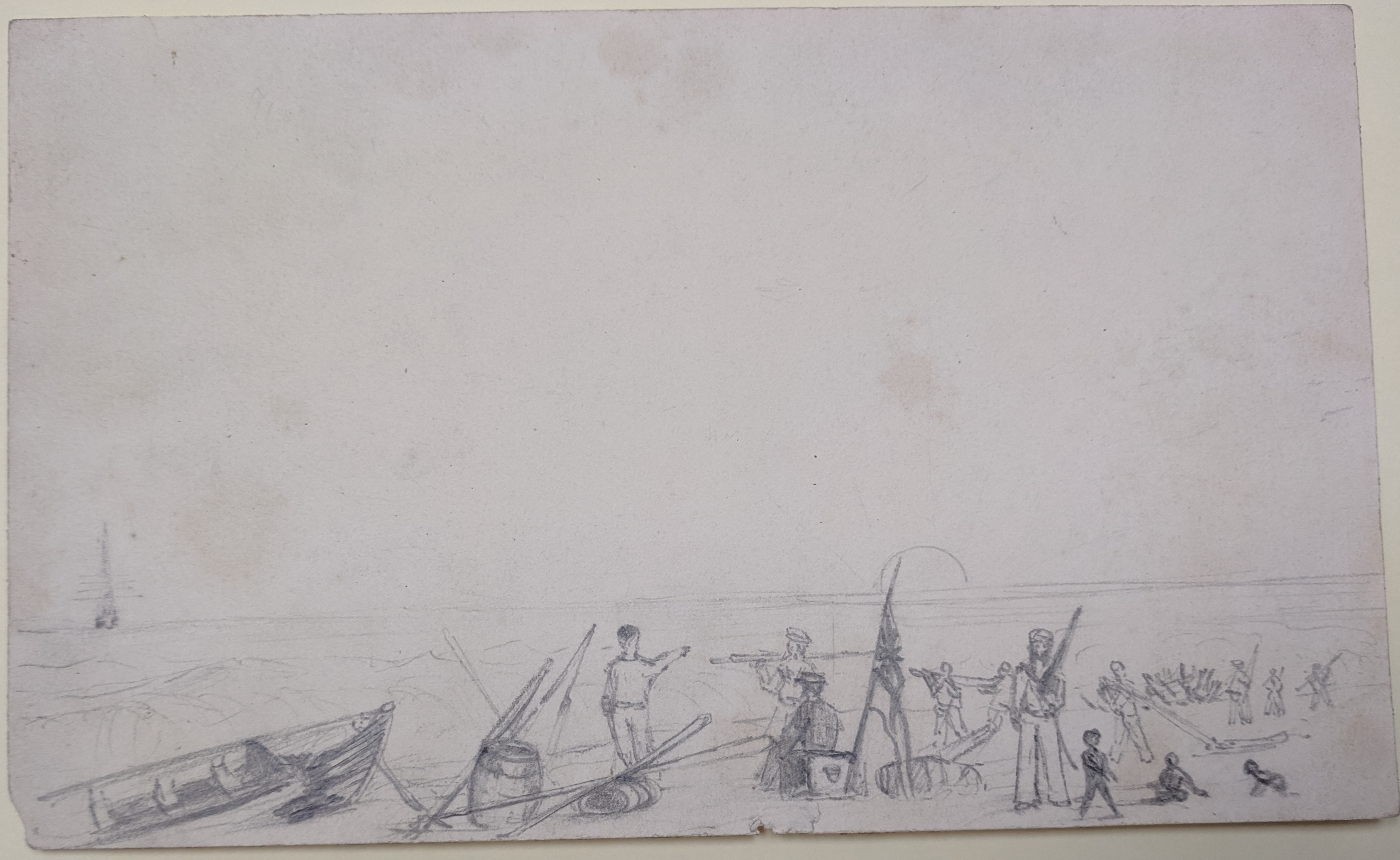

On February 6, 1869 Henn transferred to Daphne’s sister, HMS Dryad. Her main hunting ground was the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula. By May, Dryad was near the northeast corner of the Arabian Peninsula off Ras Madraka, Oman. Yet again, the crew of a dhow being chased ran the vessel ashore hoping to escape overland with any slaves that survived the wreck. Colomb sent Dryad’s cutter to a spot outside of the breakers to provide covering fire for two gigs that would land, rescue any survivors and ferry them back through the surf to the cutter. Our intrepid artist oversaw one of these gigs.

One of the gigs made it safely through the breakers but the second wasn’t so fortunate and swamped in the high surf. Luckily, Henn was in the gig that successfully landed and headed up the beach with six other crew to try and round up any survivors. When Dryad returned from yet another chase (that again ended with the dhow being run ashore), the crew found the cutter laboring through heavy wind and waves with fifty-nine men, women and children aboard. Neither gig was visible, but crew and wreck survivors could be seen on the beach. As it turned out, the surviving gig had managed to make three trips through the surf before a wave broke over the overloaded vessel and sent it to the bottom.

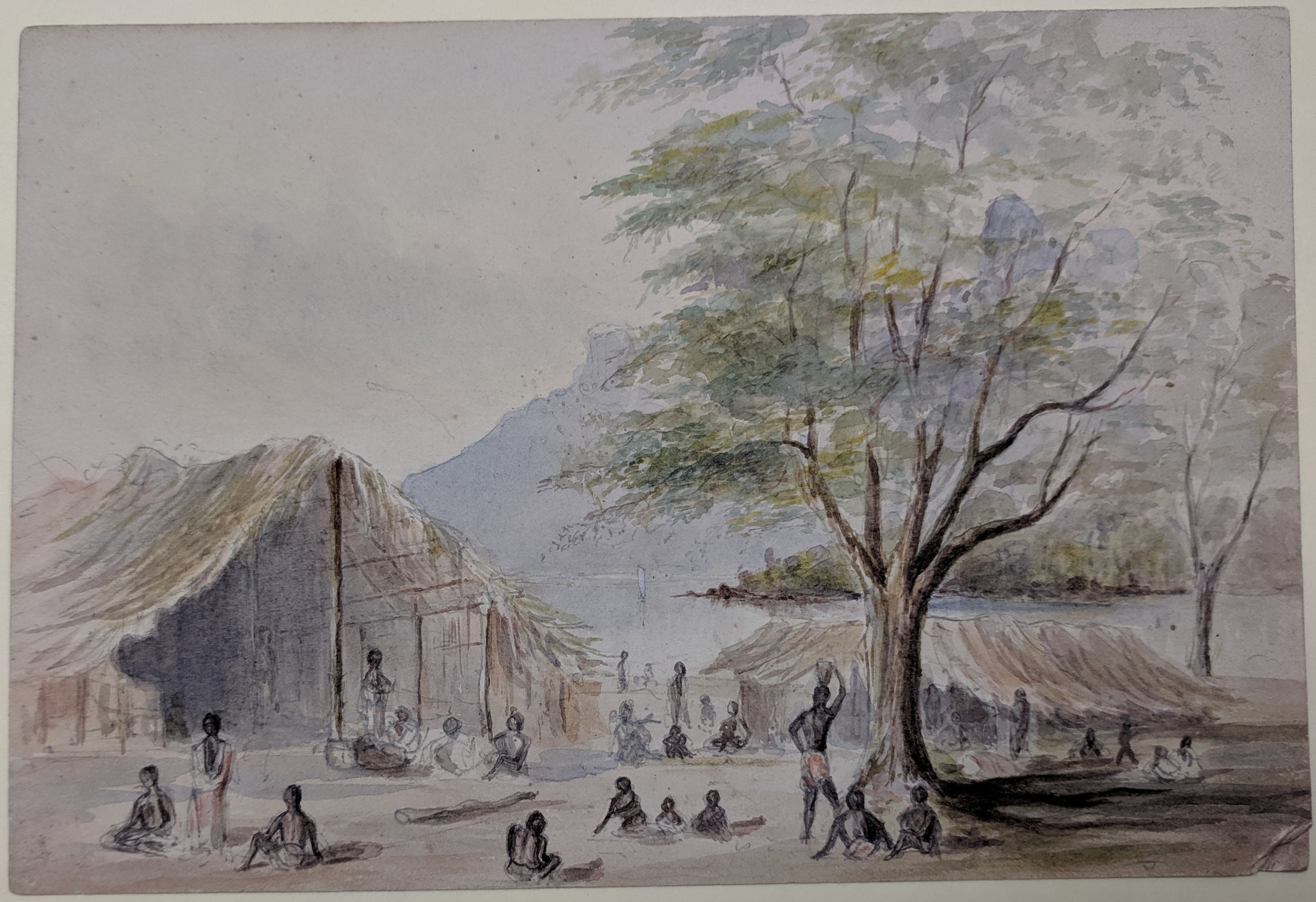

With no way to get through the high surf to Dryad, the survivors had to spend the night on the beach. To assist them, two West African men working aboard Dryad loaded their canoe with provisions and weapons and ran the gauntlet of the high waves to the shore. Although the canoe was swamped by the surf, they managed to haul it and the supplies ashore. The following day the crew and survivors marched ten miles through hostile territory to Dryad’s land base. The episode cost Dryad five crew and two boats. Of the two dhows that were destroyed only 60 of the estimated 300 enslaved East Africans held within them had been saved.

Sometimes, the Amazon’s battle against the East African slave trade didn’t involve so much chasing as much as political maneuvering with an opponent intent on concealing illicit trade. In March of 1869, Captain Edward Meara and HMS Nymphe visited the port of Majunga on the northwest corner of Madagascar. During the visit, the crew inspected dhows anchored in the harbor, but none appeared to be slaves. Towards the end of the visit, two escaped slaves swam to Nymphe and were taken aboard. After the ship left port, Meara questioned the men and learned that two of the dhows in the port had landed nearly 200 slaves a mere two weeks before Nymphe’s visit (slave trading to Madagascar was reputedly illegal). Meara immediately turned Nymphe around and headed back to Majunga. Upon anchoring, the crew were sent ashore to identify and destroy the offending dhows. Afterwards, Meara sent a note to the governor explaining that he had been “under the painful necessity of burning two dhows that had landed 200 slaves twelve days ago.”

Officials told Meara they had “reported” the landing of the slaves to their own government at Antannarivo and were awaiting a reply. None of this information had been reported to Meara during Nymphe’s official visit so he insisted the ship would not leave the port without the captives that had been landed. When the governor insisted it would take two or more months to receive a reply Meara became irate. Later that night Mears had Nymphe’s crew fire a warning shot across the fort guarding the port but didn’t dare send his men ashore to hunt for the captives. In the days that followed, Meara’s crew searched the dhows in port and managed to find another that was harboring slaves. The captives were taken aboard along with a cargo of rice and the dhow was destroyed. Unable to resolve the situation, Nymphe left Majunga leaving hundreds of Mozambique captives in the hands of the Madagascar government.

In July, when a complaint about Meara’s actions was received, Heath dispatched Captain Colomb and HMS Dryad to sort things out. While the ship was in transit, Meara and Nymphe returned to Majunga to determine whether the governor’s inquiry had been answered. While the situation was still unresolved Meara was told that 133 of the 174 captives were still alive and had been quartered among the town’s residents which, of course, prevented Meara from making any sort of search and recovery. A short time later Meara learned that an additional 120 slaves had been landed so it was obvious that the Majungan authorities were actively participating in the slave trade despite the treaty with the British indicating otherwise.

When HMS Dryad finally arrived in Majunga, Captain Colomb was armed with a letter bearing the seal of the Queen of Madagascar that stated the Mozambique captives were to be turned over to the British. After a great deal of diplomatic maneuvering that proved the Majungan authorities complicit in the illegal trade, Colomb delivered the Queen’s letter. Over the next few days 140 men, women and children were delivered to Dryad which transported them to Mauritius as refugees before continuing its hunt.

At that point, it appears Lt. Henn’s dhow chasing career ends as an article in Allen’s Indian Mail and Official Gazette dated March 8, 1870 shows Henn traveling back to England on board HMS Daphne.

According to John Broich in his book Squadron: Ending the African Slave Trade (which I whole heartedly recommend reading!) during their short “hunt” Captain Meara and HMS Nymphe released over 400 people (not including the 200 or so being illegally held in Majunga); Captain Colomb and HMS Dryad released over 360 people; and Captain Sulivan and HMS Daphne saved over 1,000.