Preparing for a tour to members of The 1805 Club I have been researching Collection items related to one of the world’s most renowned naval leaders, Britain’s Vice Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson. Our Collection holds about 665 items related to Nelson — mostly mass-produced commemorative pieces like ceramics and prints. I assumed the Club members were already familiar with the typical pieces of Nelsonia (the term applied to this sort of item) so I focused my research on the Museum’s more unique items like paintings and other artwork.

One of the more unique segments of our Nelson Collection is a scrapbook of watercolors compiled by the family of Rear Admiral William Henry Webley-Parry (1764-1837). Webley joined the Royal Navy in 1779 and served until 1825. He was promoted to rear admiral in 1837 but died just a few months after reaching this lifelong goal. Webley painted watercolors of scenes he witnessed throughout his career and kept the images painted for him by others.

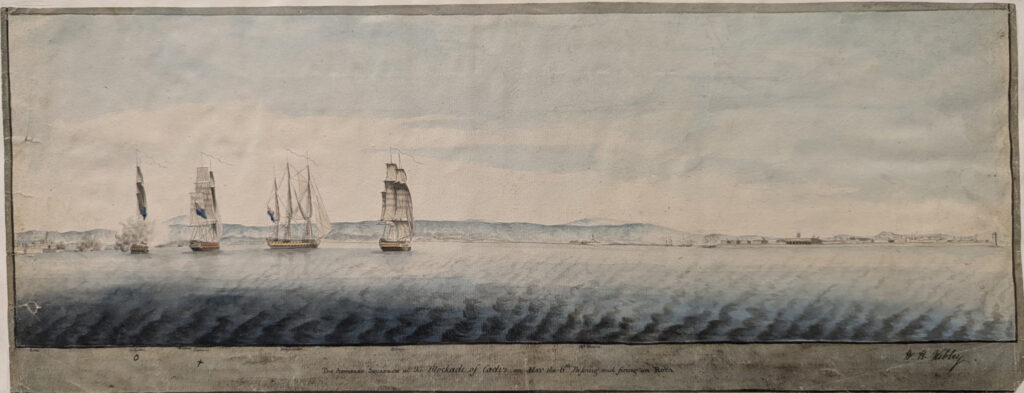

Part of what made Webley’s naval career interesting is that it overlapped Nelson’s and their paths crossed several times between 1794 and 1801. Webley first served under Nelson during the actions on Corsica in 1794 while he was stationed on HMS L’Aigle. When stationed on HMS Zealous, Webley was part of Nelson’s inshore blockading squadron at Cadiz in 1797 and fought in Nelson’s fabulous victory at the Battle of the Nile in 1798. Their last interaction occurred in the summer of 1801 while Webley commanded the sloop HMS Savage. The sloop was part of Nelson’s ‘Squadron on a Particular Service’ but as a smaller vessel, its duties were primarily focused on convoying and scouting.

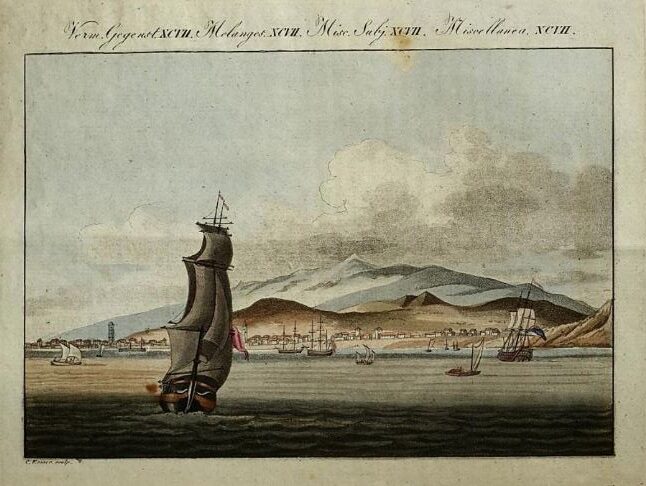

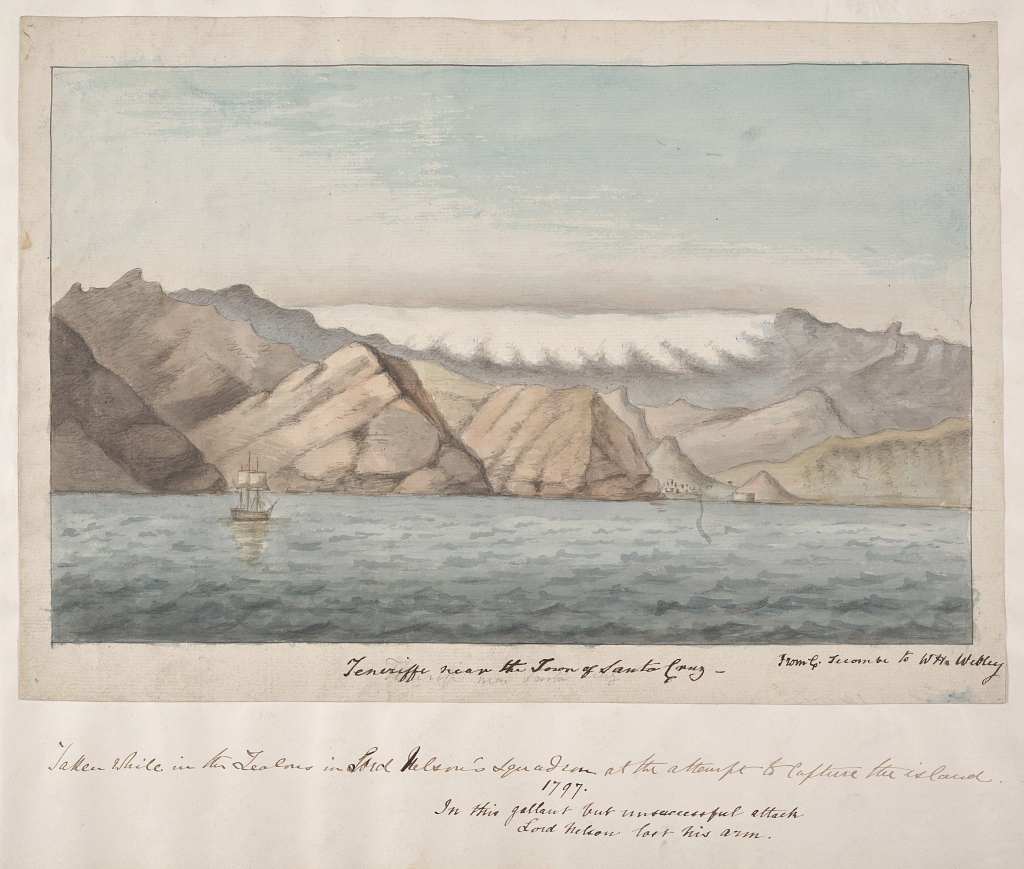

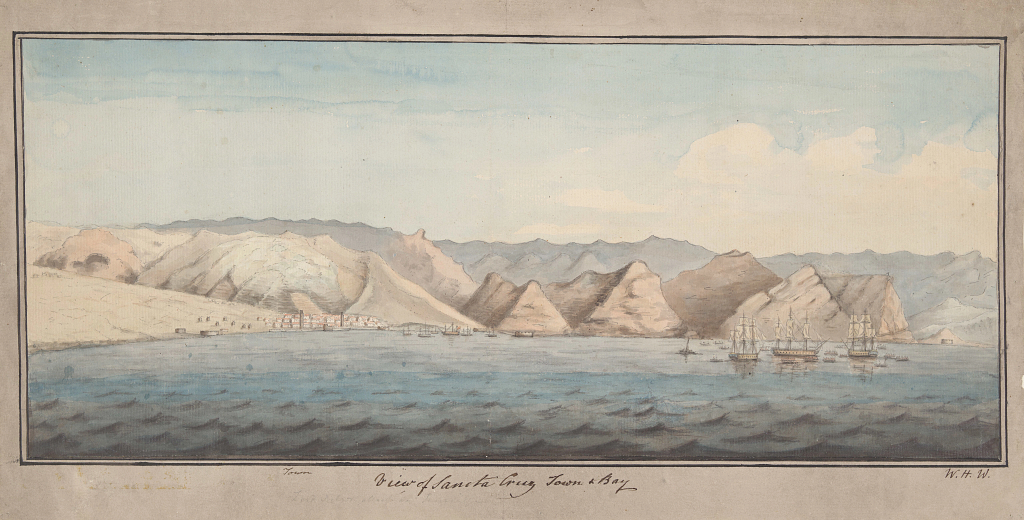

Webley participated in another of Nelson’s actions while stationed aboard HMS Zealous and it happened to be one of Nelson’s rare failures — the July 1797 attack on Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Webley’s scrapbook contains two watercolors documenting events that occurred during the attack and they are currently the only known eyewitness views known to exist. Because of the extreme rarity of images documenting this aspect of Nelson’s career, I definitely wanted The 1805 Club members to see them. By coincidence, the 226th anniversary of the action is rapidly approaching.

As first lieutenant of HMS Zealous, Webley participated in all three landing attempts at Santa Cruz and described the actions in letters to his mother. Our Archival Collection also holds a letter from third Lieutenant William Hoste to his father. Hoste was stationed aboard the squadron’s flagship, HMS Theseus, and was particularly close to Nelson. While he did not participate in the land actions, he was on board Theseus when a desperately wounded Nelson arrived there at about 2:00 AM on July 25.

I think the combination of the letters and Webley’s images provides a distinctly personal account of the action. I’ll set the story up and then let lieutenants Webley and Hoste take over telling the story of the British attack. Because I’m pulling text from multiple letters the story may feel a little disjointed but I’ll jump in periodically to make sure the events Webley and Hoste are describing are understandable.

It all started at the end of February in 1797 when the British fleet in Lisbon learned that Spain was expecting the Viceroy of Mexico with two treasure ships from Havana and Vera Cruz. Rumors suggested the value of the silver aboard the vessels was about £6 million. In an attempt to intercept the vessels before they reached a Spanish port, Admiral John Jervis detached 11 warships under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson with orders to cruise for two weeks between Cape St. Vincent on the southwest tip of Portugal and Cape Spartel in Morocco. When the treasure ships didn’t appear, Nelson’s squadron sailed to Cadiz where Jervis was establishing a massive naval blockade of the Spanish fleet.

On April 11, after hearing a rumor that the treasure ships had sought refuge at Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Nelson and friend Thomas Troubridge, captain of HMS Culloden, formed a plan to attack the island. The plan aimed at landing troops, seizing the heights over the town, severing its water supply, and threatening the town with destruction in an effort to “persuade” the Spanish to surrender the treasure ships and their cargo.

Around this time, the British frigates Terpsichore and Dido scouted the island and discovered there weren’t any treasure ships in Santa Cruz’s port, but there were two heavily loaded merchantmen belonging to the Philippines Company. The two British ships managed to cut out the smaller of the two vessels, which had £30,000 of cargo on board. The two captains later speculated to Jervis that the larger ship might be even more valuable.

In May, two more British frigates, Lively and La Minerve, visited the island and discovered the larger merchant ship was being unloaded. Again, the British conducted a cutting out — this time of the French corvette La Mutine. One of Lively’s officers told Jervis he believed Santa Cruz could be taken with “the greatest ease,” which encouraged Jervis to think that Nelson and Troubridge’s plan might succeed.

In July, when every attempt to goad the Spanish fleet into leaving the port of Cadiz had failed, an operation against Santa Cruz de Tenerife began to look much more attractive to the frustrated Jervis. On July 14, he pulled the inshore squadron blockading Cadiz and handed Nelson three 74-gun ships (Theseus, Culloden and Zealous), three frigates (Seahorse, Terpsichore and Emerald), the 50-gun ship Leander, the cutter Fox, and the mortar launch Terror, and ordered him to proceed to Tenerife. Once there, Nelson was to demand the surrender of the town, all government property and forts, and the cargo of the treasure ships, and any other cargo not intended specifically for the islanders.

Hoste: We left the fleet off Cadiz the 14th day of July in company [with] two line of battle ships, three frigates, Fox cutter & a mortar boat. Admiral Nelson’s orders were (I have this from himself) to make a vigorous attack on the island of Teneriffe at the town of Santa Cruz.

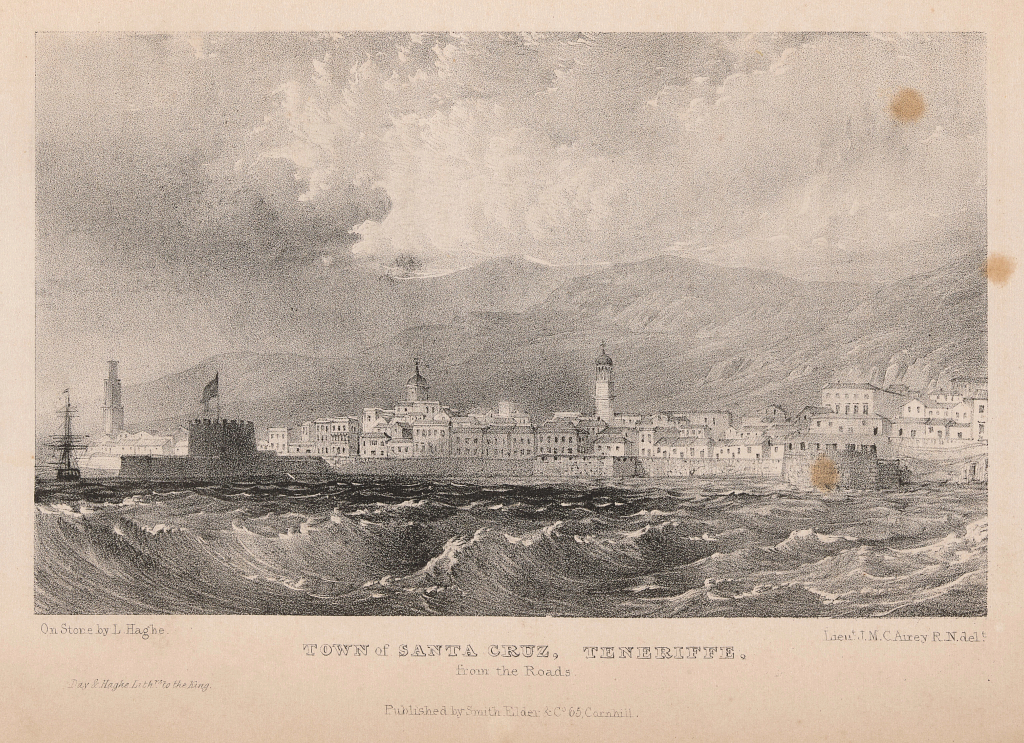

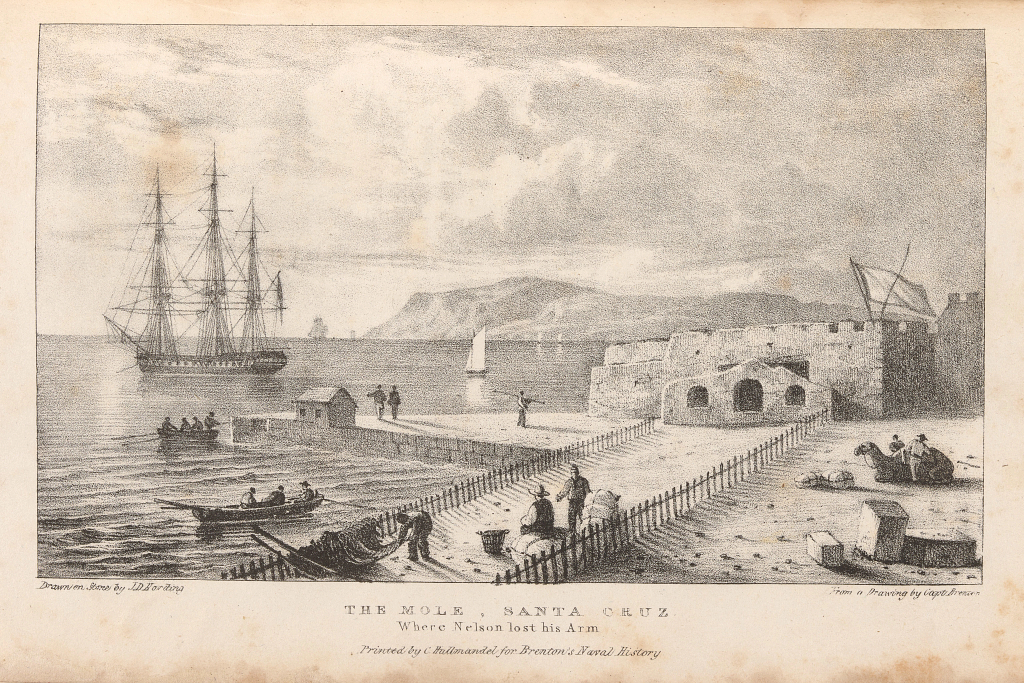

What the British don’t seem to have taken into account in their planning was how well Santa Cruz’s natural environment protected the town. Being volcanic, the island’s shoreline is sheer, the water offshore is deep, and a heavy surf pounds the slippery, broken beaches. These features make suitable landing places and anchorages hard to find. Once found, strong currents make reaching these places difficult. On the landward side, the town is protected by steep, rugged mountains. The only viable directions of attack in 1797 were from the northeast or in a direct frontal assault. To protect the town, 16 fortifications of varying sizes containing 84 pieces of artillery had been erected along the six miles of the town’s coast. An ancient castle called San Cristóbal guarded the town’s principal landing place — a low stone mole or quay that projected into the sea near the town square.

In his planning, Nelson considered the strength of the town’s defenses and felt his strongest weapon was the element of surprise (although you have to wonder how much of a surprise the attack was since the British had raided the port twice in recent months). The plan called for landing a force led by Thomas Troubridge on a beach on the northeast side of Santa Cruz. The force would storm a fort called Paso Alto and secure the heights above it to provide the squadron with a safe anchorage. Nelson gave Troubridge the latitude to decide whether to storm the town or threaten it by turning the guns of Paso Alto onto the town once the fortress was secured. Faced with Paso Alto’s guns plus those on the British ships, it was believed the Spanish would surrender to prevent the destruction of the town.

The British sighted Tenerife on the evening of July 20 when they were 35 to 40 miles northeast of the island. At that point, they hove to and spent a few days preparing for the attack. Just after midnight on July 22, the frigates of the squadron anchored about two miles away from the Castillo de Paso Alto. The squadron’s boats were filled with nearly 1,000 men and rowed to the chosen landing spot near the fort. To prevent the boats from being separated, they were linked together with tow ropes.

Unfortunately for the men in the boats, a strong gale funneling through the Bufadero Valley had raised a steep swell and a strong current close inshore delayed the landing. In the early morning light, vigilant Spanish lookouts spotted the British ships, raised the alarm, and began manning the town’s defenses. Surprisingly, rather than push their advantage while the Spanish defenses were still undermanned, Troubridge called off the landing and sent the boats back to the squadron. Considering Nelson’s character, I’m not so sure he would have made the same decision if he had been with the landing party.

Webley, with the landing party, described the event: I loose [sic] not a moment to assure you of my health and escape from some warm work at the Island of Teneriffe [sic]…On our arrival we were careful to keep at such a distance as not to be observed and embarked 900 Seamen and Marines on board the Frigates who pushed in, in the Eve so as to have attacked and stormed a strong Fort of 20 guns that commands the Anchorage of the Bay and Town of Santa Cruz, but with all our exertions we could not make good our landing before day light and therefore failed. Otherwise I have no doubt but that we should with ease and without loss of life have accomplished all our wishes.

On his return to the squadron, Troubridge consulted with Nelson and suggested trying a different landing spot to the east of the Paso Alto where he felt the men might easily scale the heights and force the fort to surrender. Nelson consented to Troubridge’s plan and sent his three frigates and the cutter Fox inshore until they were just 600 yards from the beach. The boats were reloaded and sometime after 10:00, they headed for shore.

The British forces faced little opposition as they hit the beach, but yet again the landing was made in vain. The climb to the top of the steep Mesa del Ramonal was absolutely dreadful and several men died. Once at the top Troubridge realized a deep valley separated the British from the fort. Even worse, the promontory above Paso Alto was already occupied by Spanish and French men from the town. The British dejectedly headed back down the mountain and it wasn’t until 10:00 p.m. that the exhausted, thirsty, and understandably angry men made it back to the ships.

Webley: Being now discovered, and likewise the Men of War, our mode of attack changed, and therefore landed to gain a height that commanded this Fort, intending to harrass [sic] them with Musquetry [sic] and then have stormed it. In this we were also crossed, from the excessive heat, want of water and extreme difficulty of ascending it, from which one man died and many fainted. We again embarked.

Hoste: On the 20th we made the island and early on the 22nd the Marines and small arms men belonging to the squadron (in all between 6 or 700 men) landed about 2 miles to the Eastward of the Town, but were obliged to embark again on board the frigates before night. The inhabitants being alarmed & not any appearance of success from that quarter.

At this point, the prudent thing would have been to call off the attack, but the arrival of HMS Leander and encouragement from his captains convinced Nelson to make a frontal assault on the town. With two failed landings under their belt and the element of surprise lost, Nelson, looking for redemption and unwilling to be accused of cowardice, felt he had no choice but to lead the assault. He admitted afterwards “my pride suffered” and “I never expected to return.” Unfortunately for the British, Leander’s arrival raised the suspicions of the Spanish that an attack was imminent.

Webley: Two days after, it was determined by command of the most Brave and approved Commander in our service to storm the Town and Citadel in the front of more than 70 Pieces of Cannon. It was no sooner made known than as speedily executed, and the Admiral determined to head the whole Body and each Captain his own ship’s Company.

Around 5:15 p.m. on the 24th, the British ships sailed to the northeast and anchored near Paso Alto. About two hours later, the mortar launch Terror and the frigates began bombarding the fortress. This was merely a diversionary tactic aimed at shifting the focus of the town’s defenders away from the true location of the British attack — the stone mole near the center of the town.

Hoste: At 5 came to anchor to the Eastward of the Town in company with the Culloden, Zealous, Leander, line of Battleships & of Seahorse, Terpsichore, Emerald, Frigates, cutter & gun boat standing towards the town. At ½ past 7 the mortar boat began to throw shells into the Town” [Hoste is incorrect here, the mortar boat and frigates were standing towards and firing on the Paso Alto fort].

At about 10:30 p.m., the boats of the squadron filled with 700 men assembled around HMS Zealous (Webley’s ship). Additional troops were aboard the cutter Fox (about 180 men) and a small Spanish prize the British had taken the day before (70 or 80). Even Theseus’s little jolly boat carried a few men to the landing point. They set off about 11:00 and had to row more than three miles to reach the quay (I’m sorry, did they learn NOTHING from the first landing attempt???). Nelson thought concentrating the landing force on the jetty would quickly overwhelm the Spanish opposition and believed that once the mole, town square, and San Cristóbal citadel were taken, the town’s resistance would crumble. The Spanish, however, had been well organized by Commandant General Don Antonio Guitiérrez, and were fully prepared for the attack.

Hoste: At ½ past 10 the marines & seamen from the different ships put off & began to rowe [sic] towards the Mole head under the Command of our brave Admiral.

Webley: After a Feint being made by throwing shells into the same Fort we were going to attack, at Midnight the whole Body moved forward.

Hoste: At 1AM commenced one of the heaviest cannonading I ever was witness to from the Town upon our Boats, likewise a very regular fire of musquetry [sic] which continued without intermission for the space of 4 hours.

Webley: …we proceeded in four lines, Captains Troubridge, Hood and Captains Miller and Waller leading the Boats; Captains Bowen, Thompson and Fremantle attendant on the Admiral in their Boats. We proceeded on until 1 o’clock, the Bomb Vessel keeping up a constant fire upon the Fort and Heights, when we were ordered by Captain Bowen to lay on our oars as we had just passed the mole, the intended place of landing [emphasis mine] and, at this instant or a few minutes after, the Cutter was discovered and fired upon – and before the Boats could pull round in Order, the Admiral pulled in for the Mole with orders to follow.

Webley: Shortly after we were observed, the alarm was given and the forts and citadel on all sides and in front opened on us. The word was then given to pull in and as soon obeyed, cheering and shouting under the heaviest fire I ever remember to have seen both of cannon and musquetry [sic]…

Webley: At one the Fox cutter, that had on board 200 men our boats could not carry, was discovered and as soon sunk, half were drowned, the others miraculously saved. Webley: Unfortunately owing to the darkness of night but few landed with the Admiral. However the Boats pulled in the south side of the Mole [Nelson had landed on the north side of the mole] under the heaviest fire you can conceive and Captain Troubridge, Hood, Miller and Waller made good their landing with about 450 Men (among which I have the Honour to name myself) in a very heavy surf. Unfortunately many Boats did not land owing to mistaken orders…darkness, confusion, etc., attending such expeditions.

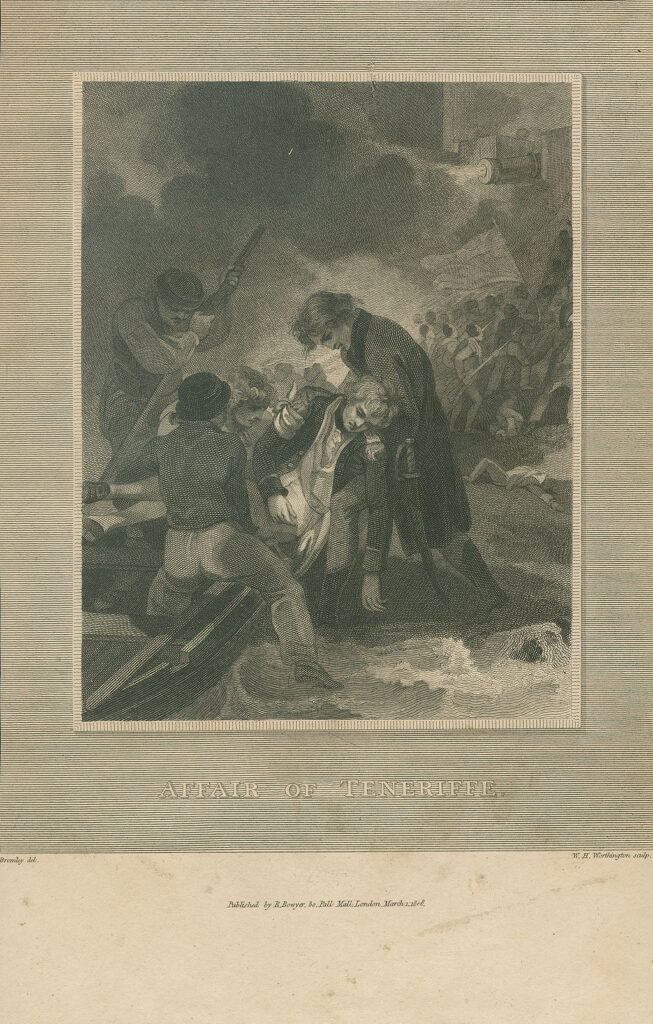

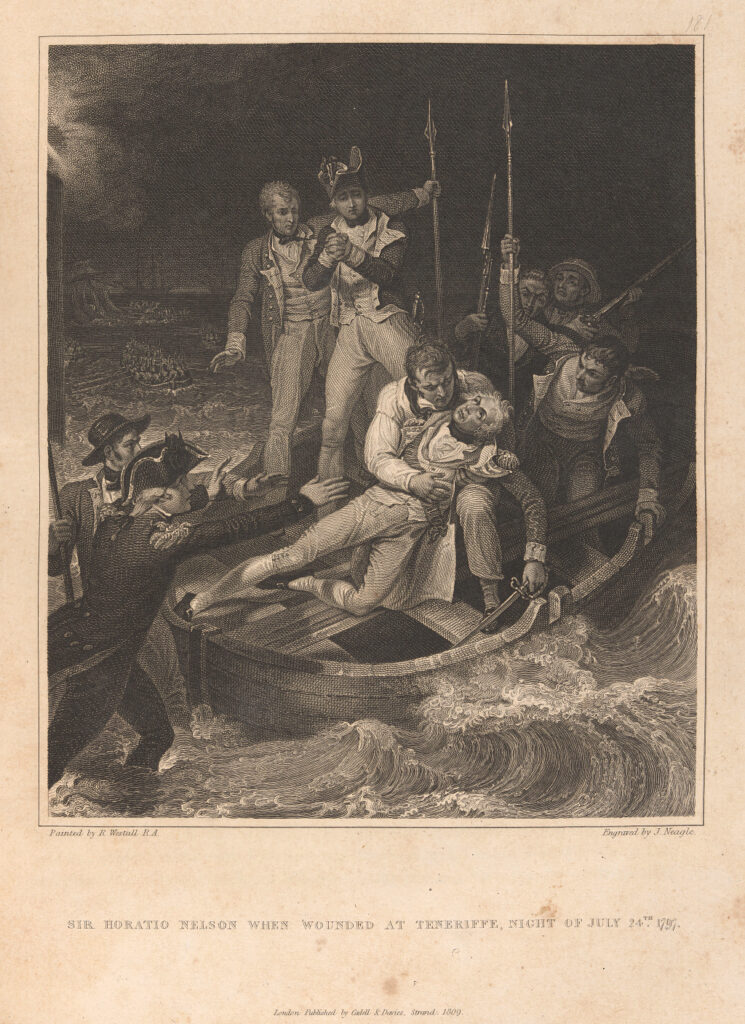

As the British approached the landing point, a small beach north of the mole, the Spanish unleashed a storm of metal from one end of the town to the other. Despite the obvious danger, Nelson ordered his division to land. Unfortunately, in the darkness and confusion, most of the other divisions missed the mole completely or were swept past it by the wind and current. Only one other division reached the mole on the north side, which left Nelson with very little support. Nearly all of the men who landed with him were killed or wounded, including him. Upon reaching the beach, Nelson’s men clambered over the bow and headed for the mole. As Nelson was climbing towards the bow, grapeshot shattered his right arm above the elbow severing the brachial artery.

Hoste: At 2, Admiral Nelson returned on board being dreadfully wounded in his right arm with a grape shot. I leave you to judge of my situation Sir when I found that the man, whom I may say has been a second Father to me. To see his right arm dangling by his side, while with his left he jumped up the ship’s side and with a spirit that astonished every one told the surgeon to get his instruments ready, for that he knew he must lose his arm & that the sooner it was off the better. He underwent the amputation with the same firmness & courage that have always marked his character…

On shore, the British attack was in shambles. Many boats were swamped in the heavy surf or dashed against the rocks and broken up. Equipment was lost. Powder was soaked. Undaunted and armed with pikes, cutlasses, and bayonets, the men who survived the landing plunged into the town from several points and fought their way to the town square to rendezvous with Nelson — neither he, nor any member of his division, arrived.

Webley: …, notwithstanding [the heavy fire of cannon and musketry] we landed 500 men in a very bad surf, which were with difficulty collected by light, having landed in different places, so that nothing material took place during the Night but continual skirmishing in the streets and the satisfaction of the inhabitants firing at us from holes and corners.

Hoste: At 4 several of the boats returned to the ship not having been able to land by reason of the fire kept up by the enemy. They gave us the unpleasant intelligence that [a] 24 pounder had struck the Fox & that she went down immediately with 150 souls on board the major part of whom were drowned. All the boats of the squadron employed saving the men. The batteries at the same time keeping up an incessant fire.

After an hour or more of waiting, the British who made it to the town square learned that other forces were sheltering in the convent of Santo Domingo. Ominously, Nelson’s division was not there, but the survivors of two other divisions were. The British in the convent made several attempts to push the action forward but ultimately found themselves surrounded and heavily outnumbered. Captain Troubridge attempted to deliver an ultimatum to the Spanish governor, threatening to fire the town if the royal treasury and the cargo of the treasure ships were not surrendered. Recognizing the weak position of the British, the Spanish ignored the threat. Troubridge then sent Captain Hood and Lt. Webley to negotiate terms of truce and withdrawal.

Hoste: At daylight, the enemy began to cannonade the shipping which we returned & soon silenced them. We now began to entertain bad hopes of our men on shore and not without reason, in less than half an hour afterwards a boat that had escaped from the shore informed us that all our people were obliged to surrender on condition that they were immediately sent on board their respective ships which was granted by the Governor.

Webley: Finding ourselves insufficient to [storm] the Citadel, a flag of truce was carried to the governor by Captain Hood, declaring that if he would provide us with boats to re-embark with our arms and colours flying, not to be considered as prisoners and likewise to give us such boats as were not destroyed by the surf. We in return promised not to re-attack that place but return from whence we came, otherways we would burn and ravage the town, which was in our power, and abide by the consequences. The whole was granted and we embarked before night with colours, etc., etc., having lost half our boats and 250 to 300 officers and men killed, wounded and drowned–among which the Admiral lost his right arm.

Hoste: At 9 A flag of truce came off from Santa Cruz with a Spanish Officer & the Captain of the Emerald…

Hoste: We left the island of Teneriffe [sic] the 27th and are now on our return to Cadiz.

The raid was a disaster. One hundred fifty-eight men were killed or missing and 110 were wounded. Despite the failure, when Nelson arrived in England he was greeted by a waiting crowd who gave him three cheers. The first lord of the Admiralty complimented Nelson on his “very glorious though unsuccessful attack on Santa Cruz.” Admiral Jervis, now Lord St. Vincent, also praised Nelson’s effort stating, “Mortals cannot command success; you and your companions have certainly deserved it, by the greatest degree of heroism and perseverance that ever was exhibited.”

No one blamed Nelson for the failure; in fact, he would soon be appointed Britain’s commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean fleet, and just a year after the disaster at Santa Cruz, he would pull off one of the greatest naval victories of the 18th century — the Battle of the Nile (August 1-3, 1798).

If you’re interested in reading the complete story of the British attack on Tenerife, I can recommend several great books. The first is 1797, Nelson’s Year of Destiny by Colin White. Another is John Sugden’s Nelson, A Dream of Glory, 1758-1797. The whole book is great, but chapters XXV and XXVI focus specifically on Santa Cruz. If you want to get the Spanish perspective on the action, try La Historia del 25 Julio de 1797 a la luz de las Fuentas Documentales by Luis Cola Benítez and Daniel García Pulido.

Endnotes

- Most of the items in our Nelson Collection came from three donors: Lily Lambert McCarthy, who founded the collection at the Royal Naval Museum in Portsmouth, England, and San Francisco collectors James Earl Jewell and David Alan Lauer.

- Nelson joined the Royal Navy in 1771 and died at the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805.

- I guess this statement isn’t technically true as I just discovered that the publication La Gesta del 25 de Julio de 1797 documents a watercolor by Webley nearly identical to our image showing the morning of July 22, 1797. The publication states the watercolor was acquired by Mr. Ernesto Groth (German consul in Santa Cruz de Tenerife) around 1920 from a German named Paulwitt, who had located it in a manor house in the west of Germany, possibly in Silesia. It is not known how the image came to be there. In comparing the two images it’s unclear which was created first. The labeling of the Groth image was done with printed characters while the text of our image is handwritten. There are also artistic differences between the two pieces such as the placement of the three frigates, which are closer to the coast in the Groth image; stylistic differences in the details of the landscape and water; and the Groth image shows Spanish flags flying on the Castillo de San Juan and the hill over the Barranco de Cueva Bermeja although it’s unclear if they are later additions.

- If I had been paying better attention, I would have put this blog out last year for the 225th anniversary. Don’t worry, the anniversary wasn’t forgotten, it was widely celebrated in Tenerife — if you had managed to beat back an attack by Nelson wouldn’t you crow about it??? There are a number of great websites and blog posts on the web if you can read Spanish!

- To “cut out” a ship means sending one or more small boats filled with men into an enemy port to board an anchored ship, overwhelm the crew, and sail the vessel from the port.

- The Castle of San Cristóbal was constructed between 1575 and 1577.

- “Hove to” essentially means putting the brakes on — sort of like pressing a car’s brakes at a stop light, the car is still running and ready to move forward once the brakes are released. You put the brakes on in a ship by turning the sails on the mainmast in the opposite direction of those on the other masts. This counteracts the drive being generated by the sails on the other masts which slows or stops the boat. Here’s a picture of ship hove to in the Mersey River: https://catalogs.marinersmuseum.org/object/CL8738

- The white stuff isn’t snow, its clouds flowing over and down the Anaga mountain range, a typical environmental feature seen on Tenerife.

- Three or four men died of heat exhaustion and two men died after falling down the mountain during the retreat.

- About 120 French sailors had been stranded on the island when the French frigate La Mutine was cut out by the British.

- From an August 9, 1797 letter from Nelson to Sir Andrew Hamond.