Howdy folks! If you’ve read my previous blog post, then you already know that this summer, I’ve been working in the Conservation Department at The Mariners’ Museum and Park as The Bronze Door Society’s Conservation Science Intern. For 10 weeks, I’ve had the privilege of working with Research Scientist Dr. Molly McGath on a variety of analytical projects related to the care and research of the Collection. As I wrap up my last week here at the Museum, I thought I’d take some time to give you an idea of the type of work conservation scientists do by writing up an overview of the things I’ve done this summer. When I started back in May, the plan was for me to work on eight or nine projects (they were put neatly into a calendar and everything). Since then, things have ballooned, as they always seem to, and I’ve now worked on 12 projects (17 if you count individual sub-projects). I figure the best place to start is at the beginning.

Project 1: Riverboat Analysis

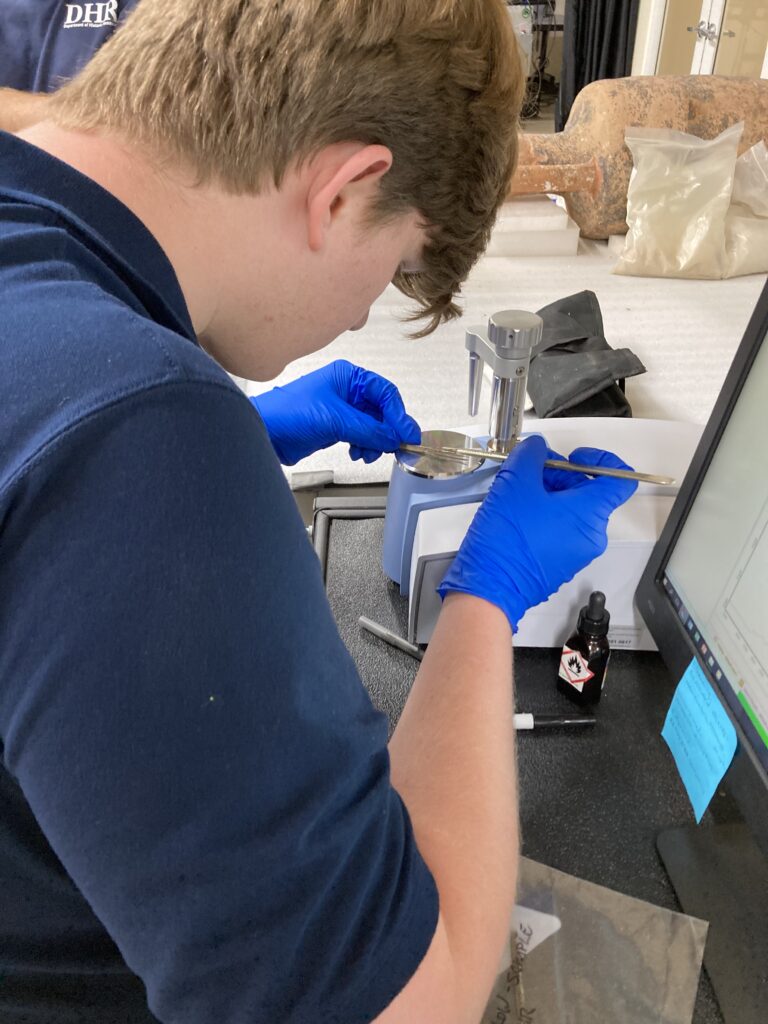

I won’t spend too much time on this project, as I’ve already written a full blog post about it. Since the beginning of my internship, I’ve been working to identify a flakey white material on the surface of an old riverboat, as its identity may have consequences on how the boat is interpreted. We’ve been looking at it with attenuated total reflectance-Fourier-transform infrared spectrometry (ATR-FTIR), x-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF), and polarized light microscopy (PLM), and two months later we’re still working on it. I’ve learned an inordinate amount about riverboats in the Shenandoah Valley though, so I guess there’s that.

Project 2: Reference Samples

Whenever the Conservation Department receives new reference materials, the Lab needs to analyze and document them so that they can be effectively referenced. In support of project one, the department bought a number of reference materials, and I was tasked with getting them ready for use. This includes measurement with ATR-FTIR and XRF, slide mounting and analysis in PLM, and research into the origin of the substance and its use. I was also tasked with designing a new form to hold all of this information.

Side Project 1: Ink Analysis/Removal

Back in early June, Paper Conservator Lindsey Zachman was preparing an object and found an ink spot that wasn’t supposed to be there. She found that it wouldn’t clean with the solvents she would normally use, so she asked Molly and I to look at the spot and, if possible, determine what materials would work best to clean it. We put the spot under ATR-FTIR, but our findings were inconclusive.

Following this experiment, Molly did some research and found that old pens and markers commonly contained diethylene glycol, which is soluble in glycerol. This led us to do some experiments to assess the impact of glycerol on paper (by adding glycerol to paper samples and examining under ATR-FTIR) and the solubility of modern marker ink in glycerol (by writing on a piece of paper and adding glycerol). There is more work to be done here, but unfortunately, this won’t be finished before my internship is complete.

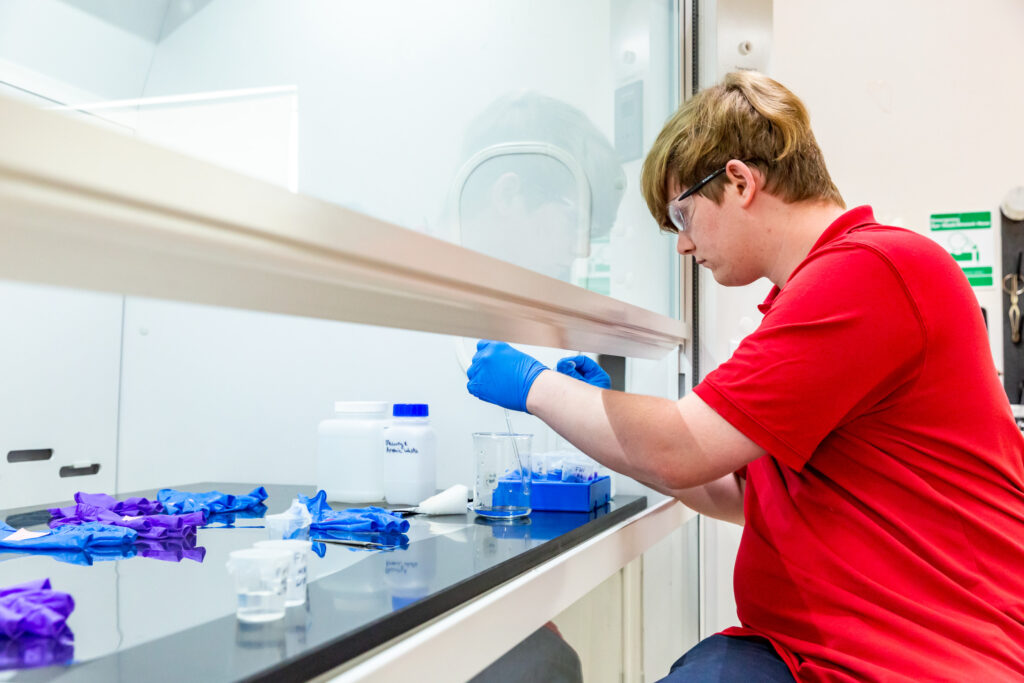

Project 3: Arsenical Books

Sometime last year, it was found that one of the books in the Collection (a volume of beautiful Chinese watercolors depicting fish) had arsenic in its pages. Working with Library and Archival Materials Conservator Emilie Duncan, we devised a method for testing how well-bound the arsenic is to the object. Wearing gloves, we performed some controlled handling of the book, then we removed the gloves, cut the fingers off, and soaked them in deionized water for 24 hours. We then tested the water for arsenic using mercury bromide spot test papers, which turn yellow/brown when exposed to arsenic. Ultimately, we found that no measurable amount of arsenic transfers to the gloves, which allows us to dispose of gloves used to handle the object in normal waste streams instead of specialized hazardous materials waste.

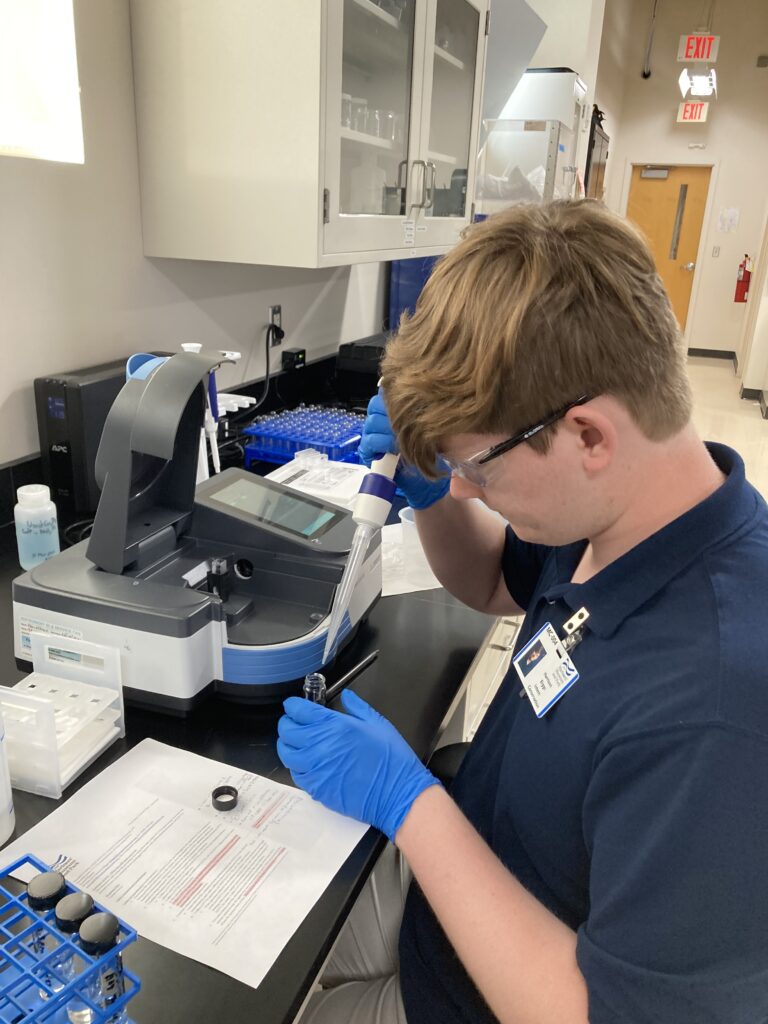

Project 4: UV-Vis Standard Operating Procedures

Ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry (UV-Vis) is a useful procedure for determining what’s in a liquid sample. It works by shining various wavelengths of light through a liquid and measuring what wavelengths are allowed to pass through and at what intensity. Different chemicals absorb different wavelengths, and the intensity that’s absorbed depends on the amount of the chemical in solution. By creating and measuring solutions of known concentration, it’s possible to correlate the intensity of absorption with the concentration of a species in solution.

My task for project four was to learn how to operate the UV-Vis spectrophotometer and then write a standard operating procedure to simplify the measurement process for others in the Lab. My work was specifically focused on measuring iron compounds in solution to help with the treatment of organic objects exposed to iron while buried in marine contexts.

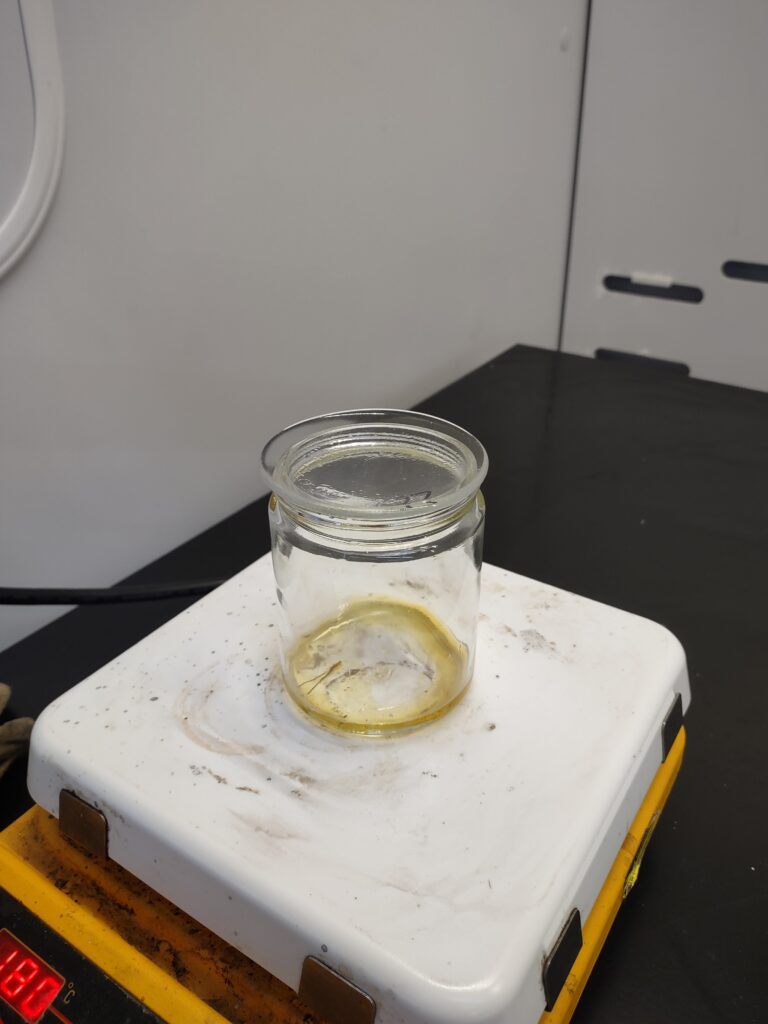

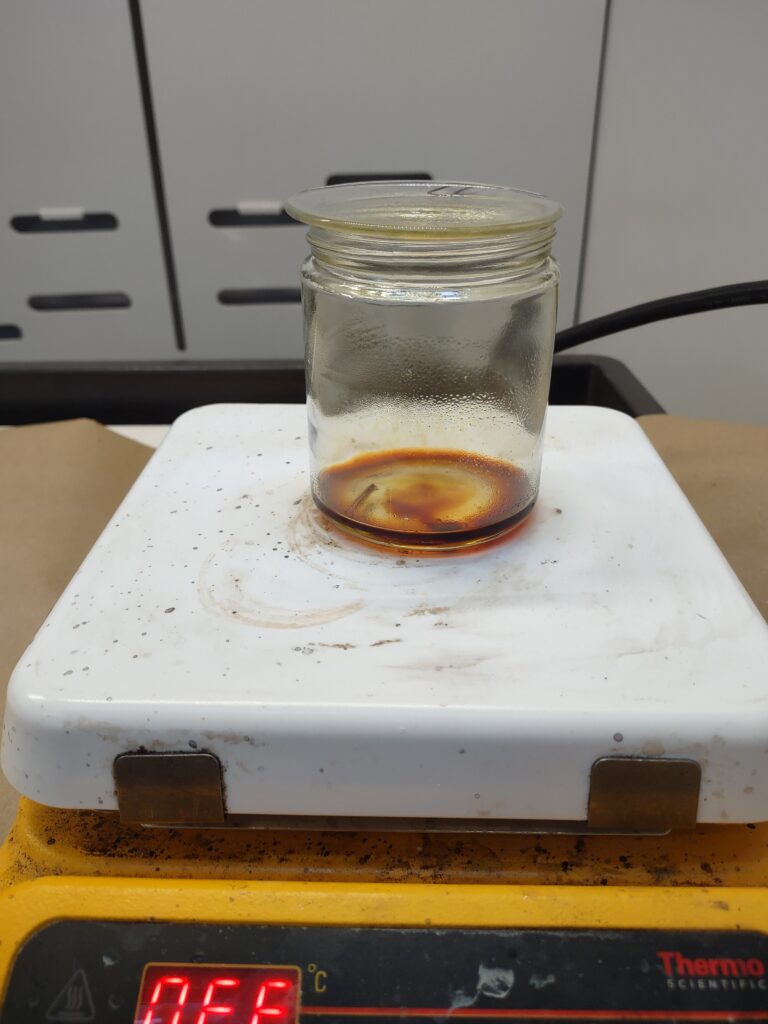

Project 5: Amphora Resin

During conservation of the amphora that’s currently on display in the Exploration Gallery here at the Museum, its interior was found to be coated in a dark resinous substance. Based on what is known about the amphora, the substance is most likely a natural pitch, a product of heating tree resin traditionally used for waterproofing. In Mediterranean amphorae, pitch was commonly applied to seal the interior for the transport of wine and olive oil.

In project five, I was tasked with shining some light on the amphora’s history by comparing the material found inside to tree resin of known origin. We acquired a sample of resin from the aleppo pine, a species of tree in the coastal Mediterranean whose resin was commonly used for coating amphorae in antiquity. The idea was to heat our raw resin until it became pitch, and then use ATR-FTIR to compare raw resin, the cooked product, and the material found in the amphora. If a good match was found between the cooked resin and the material from the amphora, then we could assume that the amphora was coated with pitch derived from the Aleppo pine. Unfortunately, our ATR-FTIR results showed that the heated resin never underwent the transformation to pitch (the spectrum was practically identical to the one gathered from the raw resin). Further experiments will probably be conducted with different cooking times and heating methods, but that will probably be after I complete my internship.

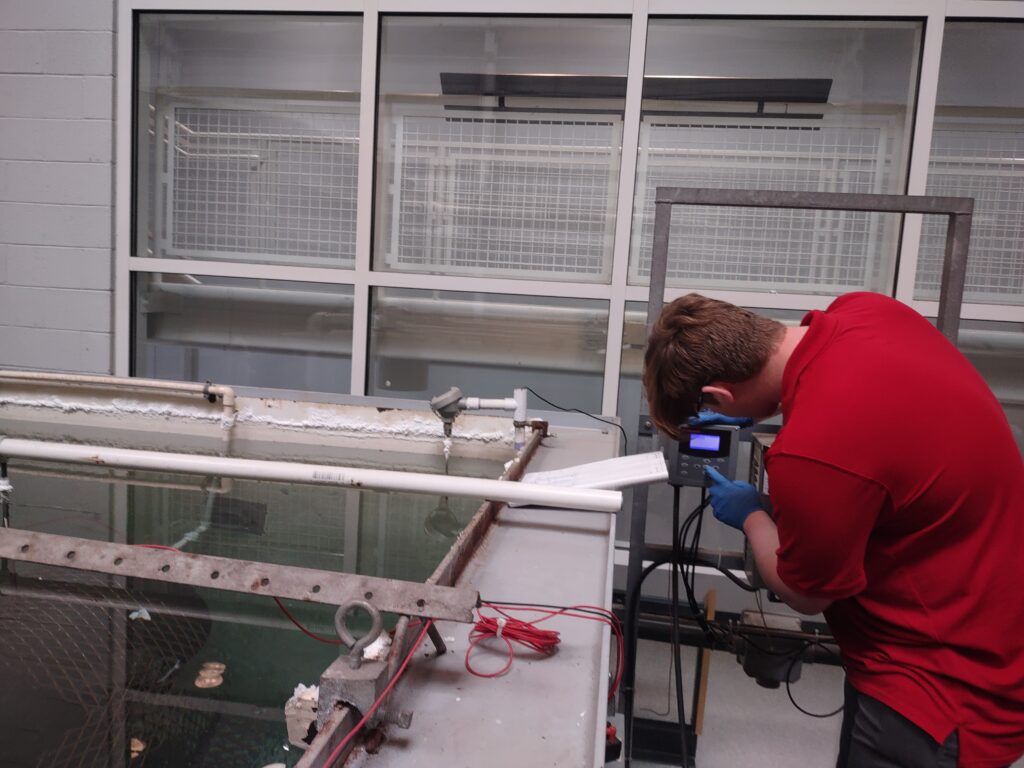

Project 6: Electrolytic Reduction Monitoring

Project six was the first of the routine projects I worked on. Once a week, Molly goes down into the Wet Lab and out to the tank farm to check the voltage on the treatment tanks that are undergoing electrolytic reduction (check out this blog post from David Krop, the former Director of the USS Monitor Center for more info on this technique) and pH on the tanks that have pH monitors. For project six, and on a few other occasions afterwards, I got to help! Checking voltage ensures the health of the objects and ensures the process isn’t too intense and forming hydrogen gas or too low, allowing corrosion to occur.

Project 7: Lake Water Monitoring

For project seven, I got to help Molly and Kelly Garner, Mariners’ Lake program manager, with the biweekly testing of Mariners’ Lake. I traveled with Kelly to the eight sites where he monitors water quality and helped take water samples and measure turbidity, dissolved oxygen, pH, water temperature, and bacteria count. The water samples were brought back to the Lab for Ion Chromatography (IC) which allows us to measure the amount of certain ions in the Lake. For more information, check out this blog post from Molly and Erica Deale, director of the park department.

Project 7.5: Lead Testing

While we were preparing for project seven, Kelly asked whether we had the capability to test for lead. Lately, the Lab has been using sodium sulfide to test for lead in some of USS Monitor’s metal treatment solutions, so Molly decided it would be fun to try testing the lake water. Once all of the lake water samples had been run through IC, we spot tested with sodium sulfide and, as expected, we found no lead in the lake water, but I got to try out a new experiment!

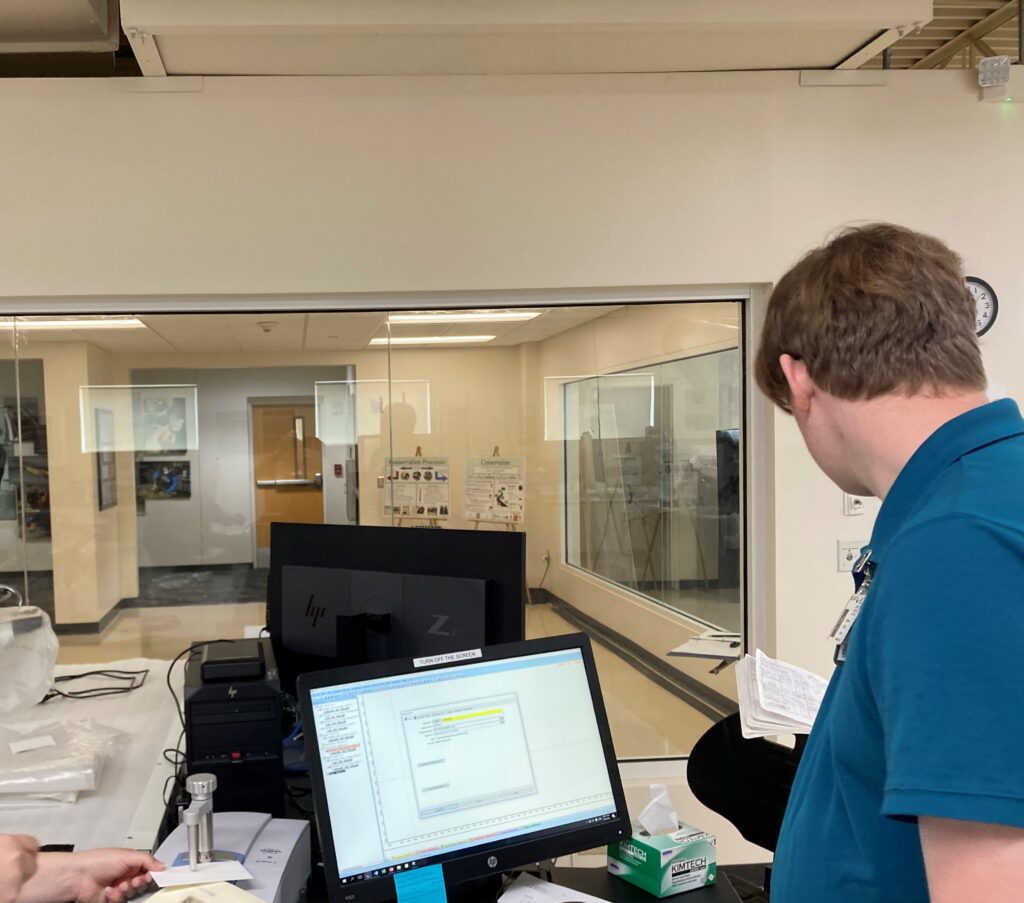

Project 8: Large Tank Survey

For my last scheduled project, I got to help with the Large Tank Survey. Similar to Electrolytic Reduction Monitoring, the Large Tank Survey is a routine check of the chloride content and pH of the tanks in the Wet Lab and the tank farm. This process occurs every two months and includes a solution sampling step and recalibration of the pH monitors. Collected treatment solution samples get brought back to the Lab for analysis in IC (we mainly look at chloride ions here, as they are a primary cause of marine metal corrosion) and measurement with a more accurate pH probe (this lets us check the quality of measurements received from the pH monitors for the tanks that are always being measured and ensures that the majority of the large tanks are basic enough).

Side Project 2: Light Testing

Recently, in support of the ongoing preventive care program at the Museum, Preventive Conservator Adam Novello has been testing a set of new UV blocking films. As part of this project, Adam, Molly, and I walked around the Museum with a light sensor, testing the films in various places and looking for hotspots where collection items might be exposed to too much light or UV. The information we gathered will help Adam prepare effective plans to care for the Collection.

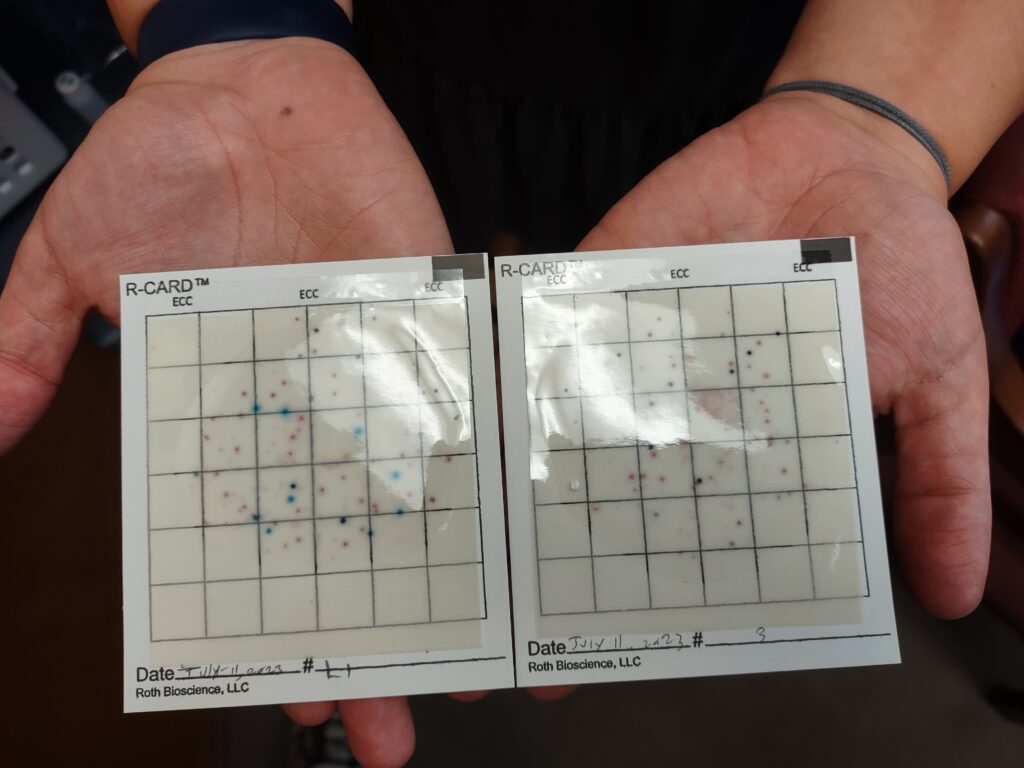

Side Project 3: Acid-Detecting (AD) Test Strips and Colorimetric Measurement

The last project I worked on was helping Molly test new conservation materials. Before any materials are allowed to come into contact with a collection item, a conservation scientist will test them to ensure that they won’t cause damage. One way to do this is to put the material in a sealed environment with an AD test strip (a type of acid-base indicator paper) for 24 hours. This tests the material to see if it’s off-gassing acids. The test strip will change color based on the acidity of what’s released.

Overall, conservation science is an extremely varied, highly collaborative discipline that does a lot to increase the knowledge of our Collections and improve our care for them. I find it especially exciting for the variety of topics and people it gives me the chance to work with. Plus, the questions and problems that get tackled are always fascinating to me. I hope you’ve all enjoyed this overview of my time at The Mariners’ Museum and Park. If you found these projects as fascinating as I do, I’d encourage you to take some time and visit the Lab to see what Molly is working on next!

ENDNOTES:

Special thanks to the Conservation team at The Mariners’ Museum and Park for welcoming me into the Lab this summer, teaching me, and giving me the chance to work with them. Their patience, kindness, and support has meant the world to me.