John looked closely at the grain of things: the grain in weathered wood in wrecks, the grain of the sea, the grain in conversations, and the everyday exchanges of life – even the sacral grain that runs through life and work. […] John’s work can make you see it. Sit yourself before The Guadalhorce Leaves Bayonne Forever and you will see that grain. John looked at life from an odd angle, so that the light would catch the grain of these things.

– Peter Stanford, Former President, National Maritime Historical Society

Leaving Bayonne

Backed by a dazzling purple sky and sailing upon dusky blue waves that reflect the rich hues of the clouds, a brilliant white ship stretches beyond the confines of the canvas. Its sails billow gently in the wind and glow with the warm light from the sun. This ship was beautiful once – it still is in a way, although perhaps more in what it represents than in its appearance.

The longer we look, the more the metaphorical cracks begin to show. Rust stains mar the bow, streaking down the bowsprit and hawesholes. The sails, once pristine, are stained and dabbed with green mildew. The old vessel sails farther and farther from the city in the background that has now become just a dot on the horizon. We sit low in the water, looking up at the bow of the white ship. Soon it will sail past us, leaving Bayonne, New Jersey as it has many times before, but this time it won’t return.

A Hidden Secret

Metaphors in art can feel like a fun little bonus – like you’ve discovered a secret meaning hidden beneath the layers of the paint. Sometimes they’re a little more obvious than others. In this work, however, the metaphor was so, so subtle until – through context and research – it became wildly apparent. I’ve said it about a number of works but this was one that stuck with me. The brilliant gleam of the sails and the rich, romantic purple called me to it. There was a mysterious air about it that said that this isn’t just a portrait of a ship leaving a port. There was something more, something deeper, an intense emotion worked into the painting with every stroke of the artist’s brush. And I wanted to know what that secret was.

The Life of Guadalhorce

Our catalog record of the painting told the story of a ship with a fascinating life and crew. A book on the artist, John Alexander Noble, noted that the artist had been enamored with the Spanish bark ever since he was a boy. This work suggested a connection deeper than just admiration, though.

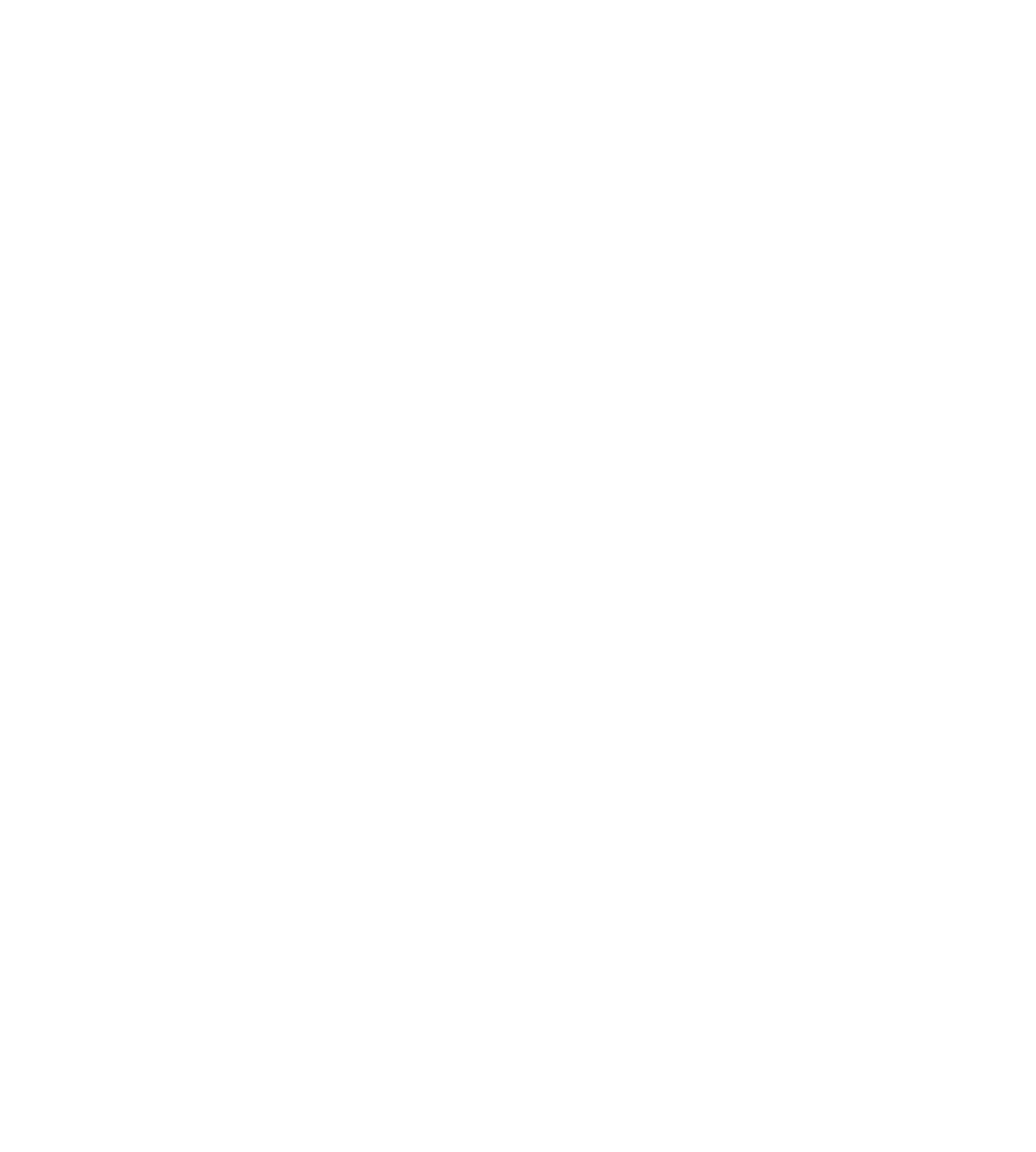

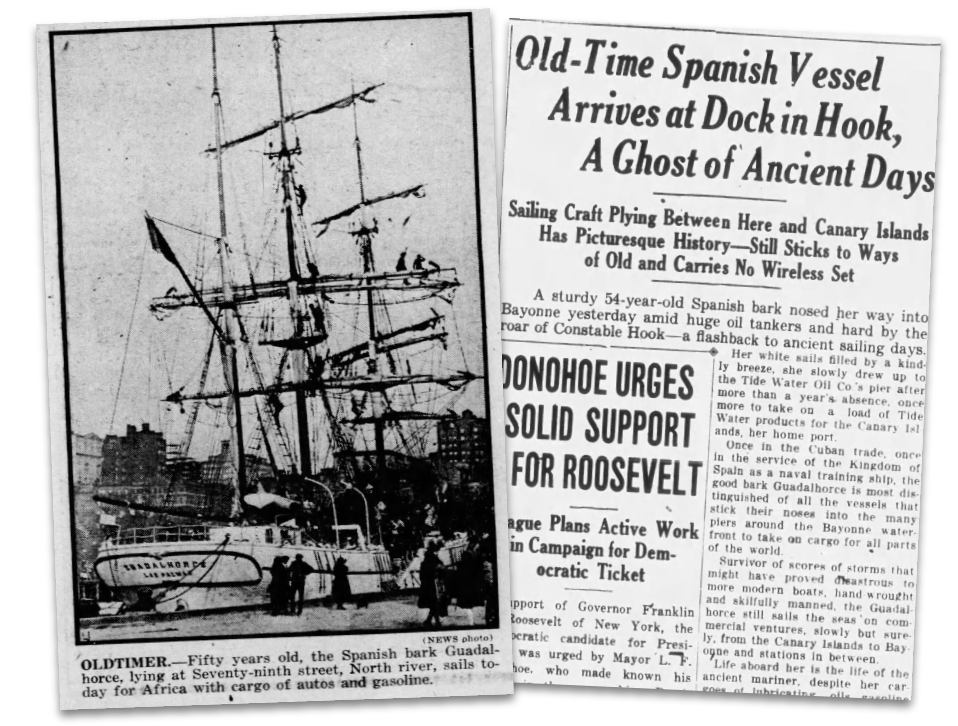

In 1867, on the Spanish island of Palma de Mallorca, the ship was built; its name was first Anibal and it was intended for use in the Mediterranean and African trade. It changed hands – and names – a few times before being renamed Guadalhorce around 1910. It was described as a three-masted vessel with a full, flaring white bow and adorned with several carved decorative elements, lovely but not ostentatious.

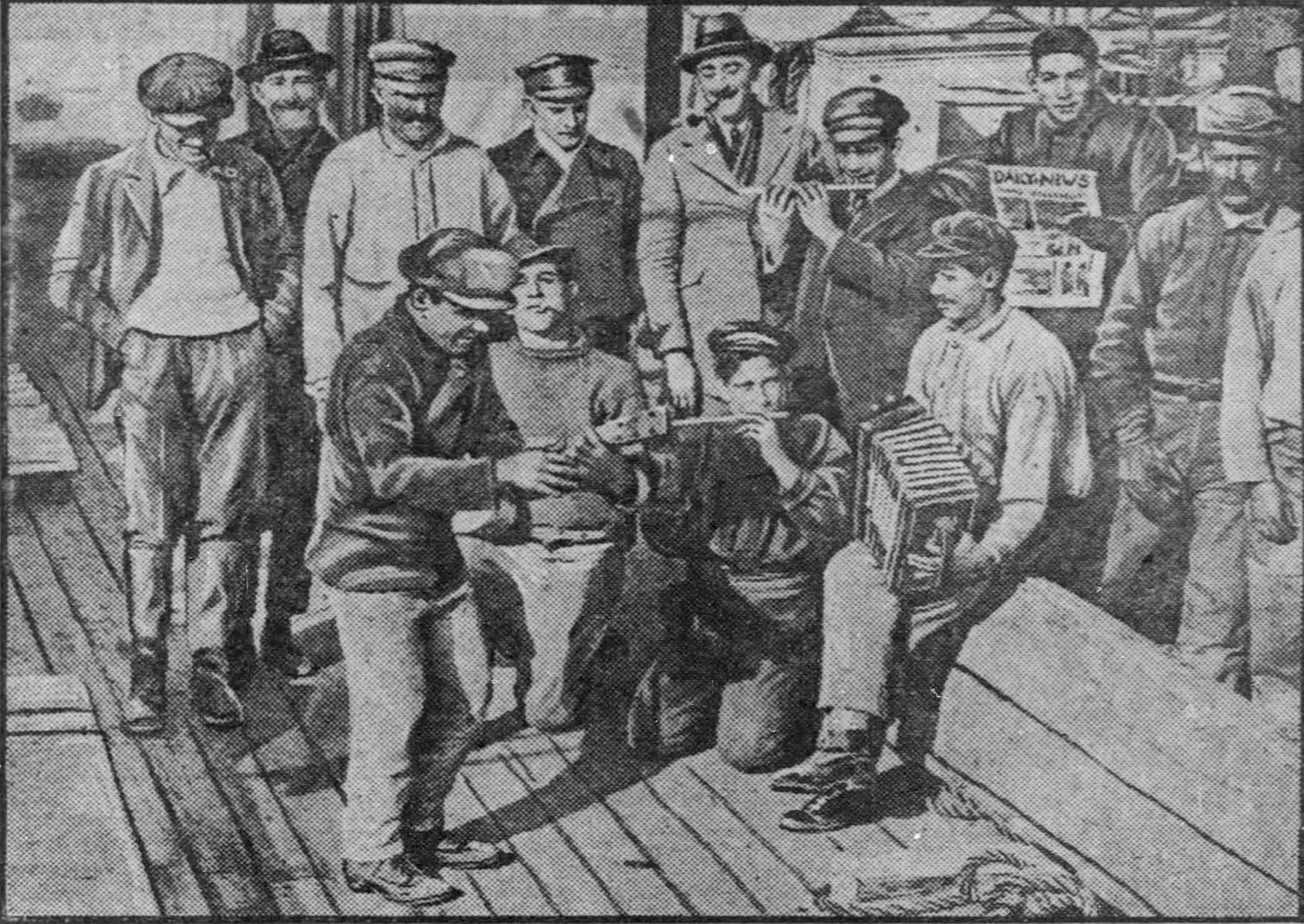

It and its crew, who were reported to be a lively, friendly bunch, were welcomed by locals and press alike whenever the ship docked in New York or Bayonne, New Jersey, where it would pick up its cargo of primarily oil, gasoline, and kerosene in its later years.

His Life was Devoted to the Sea

In 1913, three years after Guadalhorce was named, Noble was born. His young life saw moves to and from several countries and was marked by maritime travel including an Atlantic crossing to New York in 1919 at just age six, which had a deep and lasting impact. That very same year, though, marked the beginning of the end of the era of sail.

This concept was something Noble grappled with throughout his life. He felt that his existence was deeply entwined with the sailing ships that he spent his life on and loved so truly. A friend later recalled:

…his eyes would glow as if from an inner fire, and he would speak of the Sea as if of a goddess. He was passionately in love with her, even knowing the cruel hardships she imposed on her servants. It was a true love affair that never died. His life was devoted to the Sea.

– Bob Galbraith, Hulls and Hulks pg. 20

His identity as a mariner bonded him to these ships, but it’s because of that bond that he knew all too well that his lifetime would also see the end of life for the beloved vessels. It was the slow end of the age of sail that Noble captured so often in his works, especially later in his lithographs. In them he captured haunting and dramatic compositions of decaying shipwrecks, the rise of modern cargo ships, and scenes of mariners at sea that he knew would be lost as well.

His lithographs carry a heaviness that is an effect of the simple black and white printing of the works, but also in his use of chiaroscuro or the intense contrast of light and darkness to create drama. They seem dystopian in a way, like a post-apocalyptic wasteland. It echoes the heaviness of loss that Noble felt throughout his tumultuous life. Even the 1969 lithograph that reflects the same subject as this work feels heavier with the oil refineries depicted so close on the shore.

A Cherished Memory

This work, on the other hand, has a reminiscent and dreamy feel to it. If we compare it to the other treatments of the same subject – the two other paintings Noble did of this scene as well as the lithograph – we can immediately notice the difference in how these works feel. It becomes apparent how much of an impact color and artistic choices such as brushstrokes or choice of media can have on a subject – even relatively the same composition.

In this painting, he’s chosen an overall palette of rich but muted purples, something that was typical for the artist early in his career. But these dusty hues of lavender are also used to create a nostalgic, romantic feel.

This feeling is something that is emphasized by the way he has depicted the light, it’s warming and bright but not at all harsh – and contrasted against the gentle shadows, it almost gives the same effect as the warm swell of one’s chest when they bid a loved one goodbye. We’re set at such a low, close angle that we feel present in this scene. And Noble was present – this work and the other versions of this scene are all based off of a photograph that the artist took of the ship.

The artist described the moment he captured the photo and the emotion that is so palpable in this piece, saying,

I was standing on the fantail of the tug Charles Kennedy Jr. after she had dropped the bark. […] The end of the bowsprit had actually passed over my head before the engines were rung up. This collision perspective of a square rigger made an impression which time could never erase, but it was in vain that I strove to recapture it here. Guadalhorce… was the most beautiful thing on the water that I have ever seen. She radiated an aura about her, an aura of the Mediterranean Sea of a century or more ago.

A Ship and A Symbol

In looking at the color, treatment, and composition and reflecting on Noble’s life, we see what this ship meant to him, not only as a beautiful sailing vessel, but as a familiar friend, and one of the last of its kind. This work of remembrance and reflection titled Guadalhorce Leaving Bayonne Forever captures an exhilarating eye witness moment for the artist, but it also serves as a metaphor, a symbol of the passing of an era.

Its composition echoes how close it is to its end, as the ship has already begun to sail out of the scene, and soon it will slip beyond the confines of the canvas and the frame. Within a year or so after Noble bade farewell to his beloved friend, Guadalhorce was lost in a category 5 hurricane while sailing from Las Palmas to Tampa, Florida. A storm that is, still to this day, considered the worst storm in Cuba’s history.

Seven years after this iconic ship was lost, Noble painted this work. And through this work, we see the cracks that come from age, yes, but also from a life at sea, of hard work, adventure, and experience. He showed us the grain that he saw in all things, the grains that run through life. But he didn’t focus on the decay, instead, on the emotion that is in that grain that comes from living. Perhaps he painted this work as a way to say goodbye, but perhaps it was also to reminisce, to immortalize his familiar friend, and the age of sail as he saw it and wanted to remember it – glowing and beautiful, forever.

About the Artist: John Alexander Noble

John Alexander Noble was born in Paris, France on March 17, 1913 and died on Staten Island, New York in 1983. He was the son of the painter John “Wichita Bill” Noble and grew up surrounded by art, though he came to dislike the elitism of his father and his contemporaries. In 1919, the family moved to the United States. By 1929, Noble had begun to draw and filled his freetime on the water, exploring wrecks, and docks by rowboat. Seeing the “graveyard of wooden sailing vessels” (The Noble Maritime Collection) at the Old Port Johnson coal docks in 1928 was an experience that deeply shaped the young artist’s life and he returned to the site throughout his life. The artist recalled seeing the area in one of his 1977 essays, saying:

I first laid eyes on these acres of new, old, and dead vessels as a boy in 1928 from the deck of a stone schooner… I must say the sight affected me for life — and shortly thereafter I was drawing them… Well, it was but a few years more, and I was making my living there, keeping the vessels which had not yet sunk pumped out and watching their lines…

Noble’s education was, in part, funded by a family friend as his father’s alcoholism frequently left the family on shaky financial ground. After graduating from the Friends Seminary in New York in 1931, Noble returned to France where he met his beloved wife, Susan Ames. In 1932, the couple returned to the US where he continued his studies at the National Academy of Design for an additional year.

From 1928-1945, John Noble worked on the water, sailing on schooners and also working in maritime salvage it was likely his experience in salvage that led him to return to the Old Port Johnson Coal docks on the Kill van Kull (the waterway at Constable Hook separating Staten Island from New Jersey) where he salvaged parts of ships to build himself a houseboat studio, which he referred to as his “own little Leaking Monticello.”

Reflected in his accessible and relatively affordable choice of primary medium, lithography, Noble created his works for the working people:

“I’m with factory people, industrial people, the immigrants, the sons of immigrants[…] It gives life to it.” (The Noble Maritime Collection)

According to The Noble Maritime Collection’s Executive Director, the artist made 79 lithographs in a variety of numbered series and painted approximately 200 known works. The palette of his earlier works consists primarily of the purple-hued palette that can be seen in The Mariners’ depiction of Guadalhorce Leaving Bayonne Forever. Interestingly, The Mariners’ Catalog record of the painting notes that the work was made for a patron who had helped Noble secure oil paints early in his career. Upon speaking with The Noble Maritime Collection, we learned that this was not uncommon for Noble as he was known to barter and trade his works throughout his career.

Sources:

- The Noble Maritime Collection: https://noblemaritime.org/

- The National Maritime Historical Society: https://seahistory.org/award/john-a-noble/

- The Brier Hill Gallery: https://brierhillgallery.com/john-alexander-noble-1913-1983

- Hulls and Hulks in the Tides of Time – The Life and Work of John A. Noble, The Mariners’ Museum and Park Call no. N6537.N64 U7 1993 O