What You Thought You Knew

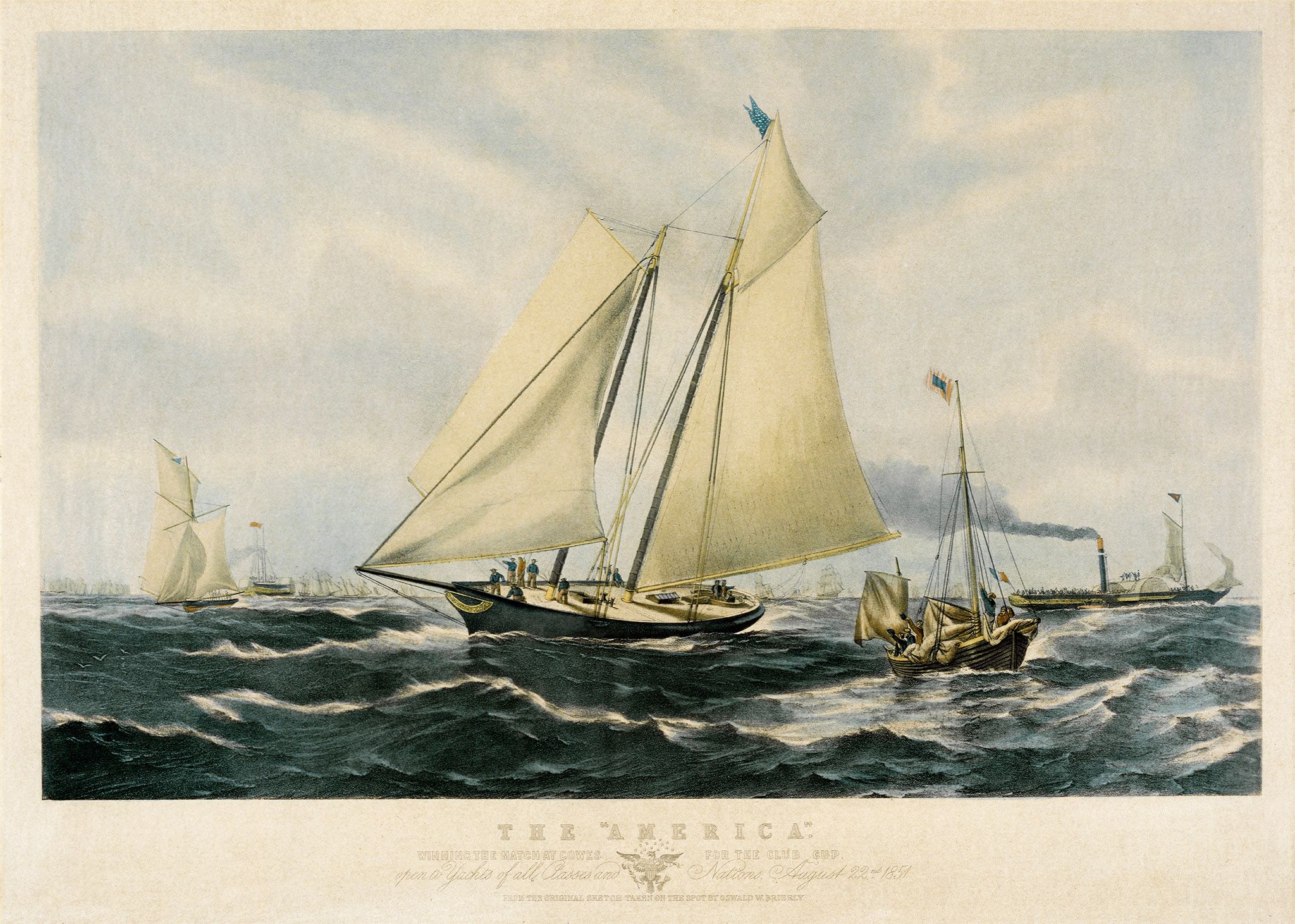

The sun begins to peek through the gray clouds as the yachts speed through the misty drizzle. It’s been an exciting race even before the starting shot rang out. The dark-horse British challenger, Galatea, along with its colorful owners and crew, defied the odds when they raced off the starting line, quickly and easily taking the lead.

That is, until it and the American defender, Mayflower, veer off course. Galatea slows, barely clearing a course buoy, and the spectator ships watching the race. It loses the lead, and Mayflower overtakes it, rounding the famous Sandy Hook lightship marking the farthest point of the course. But in this moment of fierce competition, even as it has lost the lead, the yacht in the foreground looks ephemeral. The sails are illuminated as warm light beams through a cherry blossom-pink pocket in the clouds. The vessel seems to stretch, reaching forward, and we can feel its speed and the intensity of the competition. This is the defining moment in the September 7, 1886, America’s Cup race… Or so we thought.

Reality

Reading, Researching, Re-cataloging. It might sound mundane, but it is anything but. Because within museums, this means learning, discovering, growing. It means feeling just about every emotion as you chase down a lead, a fact, or a source to find the truth. Sometimes it means finding out that what you thought you knew about something was totally wrong. And yeah, it’s frustrating, sitting there with the pages scattered around you, a journal that looks like chicken scratch, a stack of books, and about 15 tabs open. But that’s where the beauty is. At the core of this mess of searching, questioning, and consulting, there is tremendous opportunity. A chance to read, research, and re-catalog. To find out something new and start fresh.

This journey is one that I’ve been on with my Mariners’ team while preparing for this episode. We knew it would be exciting to share the story of Lt. William and Susan Henn and their yacht, Galatea, racing in the sixth America’s Cup.

(L) Clipping from Crew of the Galatea. Photographer Unknown, n.d. Albumen Print. | The Mariners’ Museum and Park. P0001.016-01–PP0410.

(R) Susan Matilda Cunninghame-Graham Bartholomew Henn on deck with pet raccoon. Photographer Unknown, ca 1885. Albumen Print. | The Mariners’ Museum and Park. P0001.022-01–PY0353.

This stunning work by beloved maritime artist James Edward Buttersworth came to the Museum with this attribution. But this is not a painting of that race.

It started with a question from one of our curators, Jeanne Willoz- Egnor, who is a valued source of knowledge on America’s Cup history here at The Mariners’. While double-checking a line of the script regarding a part of the race, she found something odd — Galatea’s hull is the wrong color in the painting.

Red flag! She alerted our team, and we dove in. But she picked apart the narrative in the painting more and more. We arrived at the center of that tangle and knew that the original attribution was wrong. So from there, we pivoted. Jeanne began to return to primary sources — eyewitness newspaper accounts and photos of the race, to books and online sources, and even consulting with one of the world’s leading experts on America’s Cup history. And everything pointed to a new story.

A New Story to Tell

Top Left: Genesta (Yacht 1884), J.S. Johnston, September 1885, Albumen Print from P.J. Grant Collection. | The Mariners’ Museum and Park. MS0267–01-08.

Top Right: Puritan (Yacht 1885), Photographer Unknown, n.d. Albumen Print from P.J. Grant Collection. | The Mariners’ Museum and Park. MS0267–01-07.

Bottom Left: Galatea, Photographer Unknown, 1886. Albumen Print. | The Mariners’ Museum and Park. P0001.022-01-145-PY0381.

Bottom Right: Mayflower, Photographer Unknown, n.d. Albumen Print. | The Mariners’ Museum and Park. MS0267–01-19-A.

Two pairs of sister ships. Two challenges for the Cup. Two America’s Cup races in New York Harbor. One year apart. The American pair, Puritan and Mayflower. The British pair, Genesta and Galatea. Taking into account that Buttersworth’s painting has included a bit of artistic liberty and several inaccuracies, we now believe that this is not a race from the sixth America’s Cup in 1886, but instead, the first race of the fifth America’s Cup, which occurred on September 14th, 1885. During this race, the other set of sister-ship competitors, Puritan and Genesta, raced in similar conditions, with a similar outcome — Puritan managed to beat out the British challenger, defending the Cup. This work captures the action in that race as Puritan rounds the Sandy Hook lightship with only a slight lead over Genesta.

Onward

So, where do we go from here? Onward. There’s beauty in being wrong, which is reflected in Buttersworth’s work. Even if it does depict the 1885 race, as we currently believe, Buttersworth has still gotten several elements wrong: the subtle differences in the sail colors, the details of one of the hulls, the yachts’ proportions, and the owner’s private signal flag on the vessel in the foreground.

It’s not perfect; it’s likely not an eyewitness account as we thought it could be. But that’s okay. We can learn from it and appreciate it for what it is—a story, a work of art.

We’re not perfect, either. We get things wrong sometimes, but it is part of our charge and our purpose here at The Mariners’ to seek the truth, to not be complacent and blindly accept the information presented to us. We are called to question, to read, research, and re-catalog. To learn, discover, and grow. And that’s exactly what we’re going to keep doing.

The Journey: An Interview with Jeanne

Special thanks to Curator of Maritime History and Culture and Director of the Ifland Center for Exploration, Jeanne Willoz-Egnor, for sitting down with me. We went through the research process together, but wanted to take this opportunity to dive a bit deeper into what led us to this re-attribution and share the full scoop with our readers and viewers!

Kyra: So, Jeanne, we’ve been on a bit of a wild ride with this piece. But before we dive into our research journey, can you tell us a little bit about the America’s Cup?

Jeanne: The America’s Cup is the world’s oldest international competition. It started after an innovative American yacht entered and won a race against boats of Britain’s Royal Yacht Squadron in 1851. The trophy won by George Steers’ yacht America was donated to the New York Yacht Club to be used as a perpetual trophy in a sailing competition between foreign countries, and the competition to possess that big silver cup is still going on today.

K: And that story is told in our Speed and Innovation gallery, correct?

J: Yes, Museum guests can experience the thrill of the America’s Cup and learn about the astounding technologies used to design and sail the contest’s racing yachts.

K: Awesome, so let’s get back to the big question — what’s the real story behind this painting? We always want to make sure we’re telling the correct story when interpreting our Collection. So, Jeanne, what caught your eye and started the questioning of the attribution of this piece?

In the original script for this Beyond the Frame episode, we relayed an event in which a spectator boat blanketed Galatea which allowed Mayflower to pull into the lead. While reviewing the history of the race in several publications I discovered an inconsistency in the reporting of the event. Curious as to whether the event had even occurred I decided to read the original newspaper descriptions of the races to see if it was discussed.

As I was reading, I realized there was a discrepancy between the physical description of Galatea in the newspaper articles and other sources and how she appeared in our painting. Everything I was reading indicated the hulls of both Mayflower and Galatea were white.

Knowing that artists do make mistakes and artistic choices in their portrayals of vessels I decided to look at original photographs of the race in our collection. Those photographs showed that the hulls of both vessels were indeed white during 1886 races and that convinced me that the boat in our painting couldn’t be Galatea.

K: So, what did you do next?

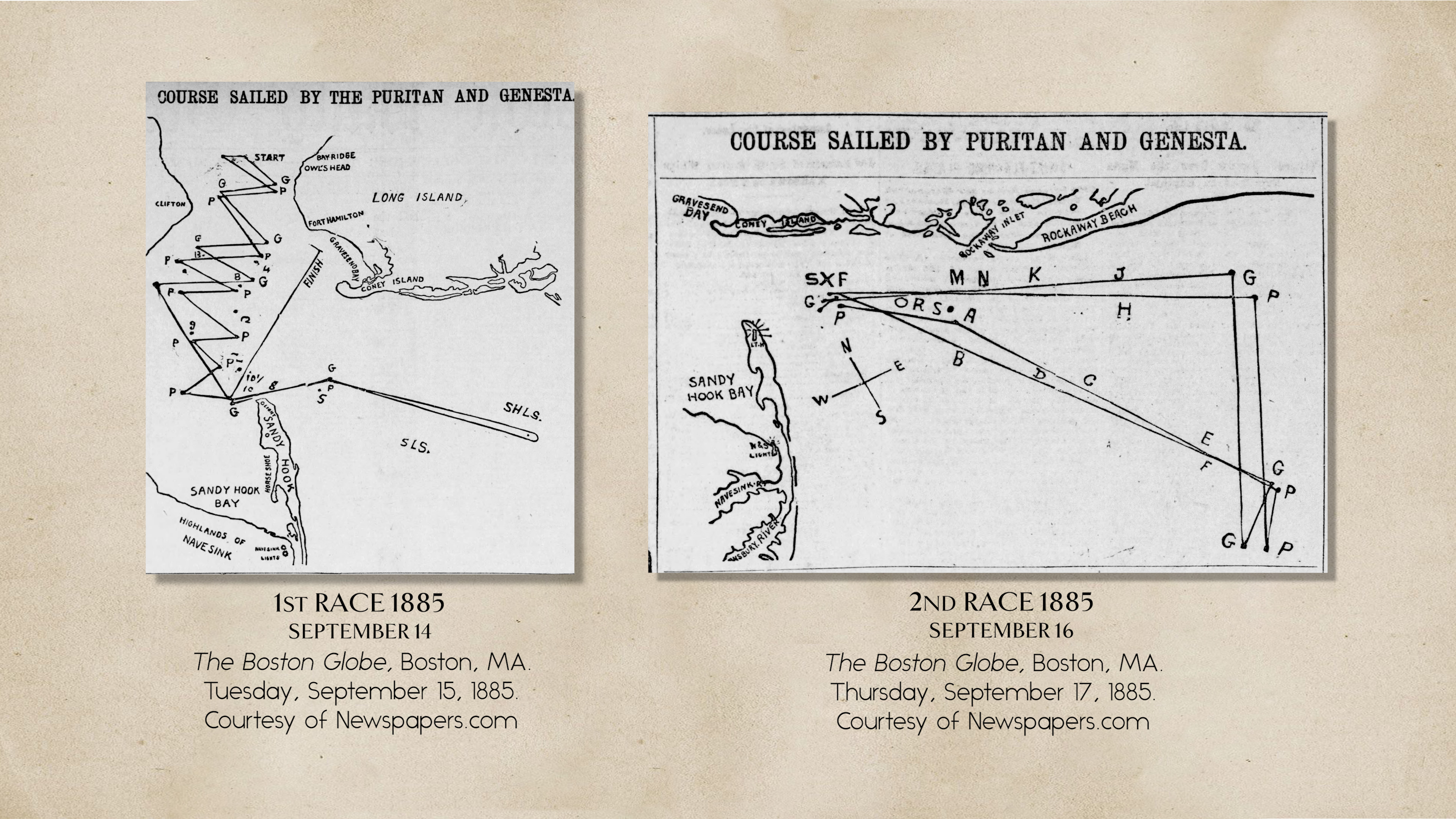

J: I continued researching and learned that there were only three other races sailed by single-masted cutters in the history of the America’s Cup. Only one of those races featured boats with the right hull shape and colors and those boats matched our painting. At this point we began to theorize that our painting actually depicted the 1885 contest between Puritan and Genesta.

K: So the painting might actually show an America’s Cup race that happened one year earlier than we originally thought?

J: We believe so, yes. But, Buttersworth’s painting does include some features that made me unsure of the new attribution, namely that presence of so many schooners and sloops sailing in the background. This made me wonder if the scene might portray a New York Yacht Club regatta.

Whenever my research hits a wall like this and it involves the New York Yacht Club and the America’s Cup I always turn to my friend Steve Tsuchiya for help. Steve is a very knowledgeable America’s Cup and New York Yacht Club historian.

K: What did Steve think?

J: Steve had a few ideas after looking at photographs of the painting. The first thing he noticed was that the boats in the foreground aren’t flying national flags like the boats in the background. To him this suggested the scene shows a match race.

And because the scene includes the Sandy Hook lightship he felt it was a race occurring on the New York Yacht Club course or another local club course.

He also noted that the rig and hull design shows boats circa-1880s and that the black-hulled boat has several features indicating it is British such as:

1) a quadrilateral club topsail which the English tended to use more than the American’s, and

2) a rectangular private signal which is an English style

Considering this, Steve agreed with our theory that the painting depicts the 1885 America’s Cup match between Puritan and Genesta. After reading original accounts of the two race days, I learned that the race on September 16th used a course that didn’t include the Sandy Hook lightship; this convinced me the painting can only depict the midpoint of the September 14th, 1885 race.

Even after talking to Steve, I was still curious about the number of sailing boats present in the scene. I returned to the original newspaper accounts and discovered that it was typical to have hundreds of steam and sailing boats following the racers around the course. While the steamboats were fast enough to reach the Sandy Hook lightship and watch the racers rounding it, the sailing boats were not, so they tended to sail part way out to the lightship and then turn around and head back to the next buoy on the course.

K: Wow. So, now we have a new attribution. And possibly an entirely different story to interpret, which is exciting, because that’s what it’s all about. Continuing to ask questions, finding the truth, all so that we can better connect our Collection with the world.

J: Exactly! I learn new things about the objects in our Collection every single day. Making sure the information we put out into the world is factual is one of the most important things we Mariners’ can do. A 2021 survey by the American Alliance of Museums found that museums are the most trusted source of information in the United States, so increasing our understanding of the objects in our Collection is always one of our highest priorities.

Watch the full episode here!

About the Artist: James Edward Buttersworth

James Edward Buttersworth was born in 1817 near Greenwich, England. His father was the British maritime artist Thomas Buttersworth, from whom he drew much inspiration. James emigrated to America with his family between 1845 and 1848 and settled in Hoboken, New Jersey, which provided him easy access to view the races in the New York harbor. He is considered one of the premier maritime artists. It is estimated he painted more than 500 works of ships that chronicle the evolution from sail to steam. As a maritime artist who lived near a hub of American yachting during the sport’s “Golden Age,” it makes sense that more than 250 of those known paintings depict the vessels and racing around New York. The Mariners’ Museum and Park’s Collection includes 26 works by the artist and two additional works attributed to the artist. Many works, especially those of yachts, are quite small – this particular work measures just 12” x 18” without its frame. Smaller works like this were profitable for artists as they could be commissioned and purchased by the yacht owner and then hung in the vessel’s cabin.

James Edward Buttersworth is best known for his paintings of ships that are painted with a fine and dramatic treatment of light and action to help carry the narrative through the painting. His brushstrokes are very precise, even in these small works, and he includes a great amount of detail. Though some works are possibly eyewitness accounts, he likely painted others from accounts of races, so some details are more subjective. Buttersworth died of pneumonia at the age of 76 on March 2, 1894, at his home in New Jersey.

Sources:

- The Mariners’ Museum and Park, B is for Buttersworth Exhibition files, October 2015-April 2016.

- J.E. Buttersworth: 19th Century Maritime Painter, Mystic Seaport exhibition catalog. June 7 – September 3, 1975.

- “J. E. Buttersworth: Painter of Sail and Steam” by J. Revel Carr. Nautical Research Journal, September 1976, pg 111-

- Christie’s, New York City. May 23, 1996 Auction Catalog.

- Ship, Sea & Sky: The Marine art of James Edward Buttersworth, NY: South Street Seaport and Rizzoli Press, 1994.

- Museums and Trust by the American Alliance of Museums. September 2021