USS Cumberland, flagship of the US Navy’s Home Squadron, was dispatched to Gosport Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Virginia, upon the sloop’s return from a brief cruise to Veracruz, Mexico. It was hoped that the warship’s presence would deter any effort to capture the yard during the secession crisis. Gosport was the largest and most advanced navy yard in the United States. Besides its granite dry dock and other ship repair/construction facilities, Gosport housed 14 warships, including the steam screw frigate USS Merrimack awaiting repair and others in ordinary like USS Raritan. The Cumberland, then commanded by Captain Garrett J. Pendergrast, was anchored just off Gosport so its firepower could be utilized to defend the yard or cover the release of ships.

Three days after Virginia left the Union on April 17, the Union abandoned the yard. Cumberland’s crew helped to destroy the facility and various ships. By 4:20 a.m. on April 21, Cumberland, loaded with sailors and Marines, was towed out of the yard by USS Pawnee supported by the tug USS Yankee. Cumberland slowly passed the burning Merrimack, not realizing that what seemed to be a burning hulk would become the sloop’s death knell less than one year later.

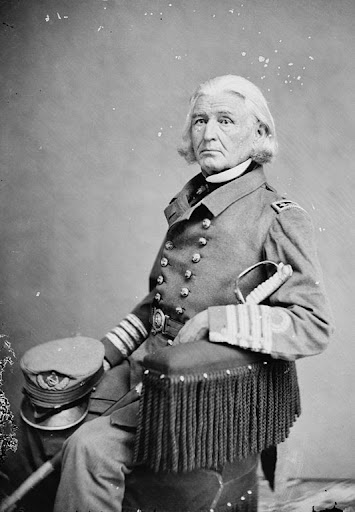

ca. 1843-1848. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Increase of the US Navy

Following the War of 1812, Congress passed an “act for the gradual increase” of the US Navy in 1816. Several ships of the line and frigates were to be constructed. One of these, USS Cumberland, was laid down in 1824 at the Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston. Designed by William Doughty along the lines of USF Constellation, the frigate was part of the heavily armed Raritan-class.

Money Troubles

Brady-Handy photographers, ca. 1860-1875.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Financial issues delayed Cumberland’s completion. The frigate was commissioned on November 9, 1842, and placed under the command of Captain S. L. Beese. The vessel became the flagship of Commodore Joseph Smith’s Mediterranean Squadron. After an uneventful cruise, Cumberland returned to the United States and was immediately pressed into service as the Home Squadron’s flagship. Commodore David Conner commanded the squadron; Thomas Dulay captained Cumberland. When Dulay became ill, Captain French Forrest replaced him. The Cumberland ran aground July 28, 1846, off the coast of Alvardo, Mexico. Eventually, the frigate returned to Hampton Roads, Virginia, for repairs at Gosport Navy Yard.

In the Mediterranean Sea

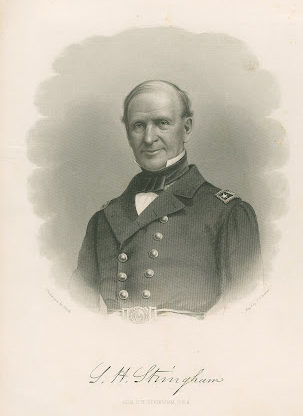

Cumberland then had two cruises as part of the Mediterranean Squadron: 1849 to 1851 and 1852 to 1855. The third deployment was action-packed as the frigate served as Commodore Silas Horton Stringham’s flagship. Cumberland supported the work of George Perkins Marsh, environmentalist and ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Marsh had to intercede with King Otto of Greece about the treatment of American missionaries. More importantly, was Marsh’s diplomatic work when the Crimean War erupted. March and Stringham offered the flagship as a safe place for Americans who needed assistance or protection when the conflict began.

After this three-year cruise, Cumberland was sent to the Charlestown Navy Yard, where the ship was razed into a sloop of war and rearmed. The warship was now better able to serve the needs of the US Navy as it was faster, lighter, and less expensive to operate. The new armament included twenty-two IX-inch Dahlgren shell guns and two X-inch Dahlgrens as pivot guns.

USS Cumberland (Razee) Characteristics

Length: 175 ft.

Beam: 45 ft.

Draft: 21.1 ft.

Armament:

one X-inch shell gun on fore spar deck pivot

one 70-pounder rifle (probably 60- or 80-pounder Parrott) on aft spar deck pivot

22 IX-inch Dahlgren shell guns

On Slave Patrol

The repairs were completed in 1857 and Cumberland was sent to the west coast of Africa as the flagship of the African Squadron. This squadron’s primary duty was the suppression of the slave trade. In 1859, the sloop returned to the United States and was named flagship of the Home Squadron and assigned to the Gosport Navy Yard.

Flashpoint Gosport

When Virginia left the Union on April 17, 1861, all eyes were on Gosport Navy Yard. Located on the Elizabeth River in Portsmouth, Virginia, and was capable of building any warship the nation needed. Gosport’s commandant, Flag Officer Charles Stewart McCauley, was not up to the task of defending the yard against the Virginians who were demanding control of Gosport. Union secretary of the navy Gideon Welles ordered McCauley to get USS Merrimack ready for sea. However, the commandant hesitated and refused to allow the steam screw frigate to leave Gosport. Flag Officer McCauley’s indecision and inaction were based on Welles’s order: “Do nothing to upset the Virginians.”

The 67-year-old McCauley had served in the US Navy since he was fifteen. Rumor had it that he had taken to drink, and he was ridiculed for being too old for active command. Recognizing that McCauley was unable or unwilling to defend the yard, on April 16, 1861, Welles ordered Captain Garrett J. Pendergrast to keep Cumberland at Gosport because: “events of recent occurrence and the threatening attitude of affairs in some parts of our country, call for the exercise of great vigilance and energy at Norfolk.”

Pendergrast then moved Cumberland up the Elizabeth River to a new position near the Portsmouth Naval Hospital just off the naval yard. The sloop could be utilized to defend the yard or cover the release of ships in port. Besides Merrimack, USS Dolphin, Germantown, and Plymouth were the only warships considered in relatively good condition to warrant saving. Welles needed every available ship for blockade duty.

On April 20, 1861, McCauley, believing his command was surrounded with no relief in sight, made the fateful decision to abandon and burn the yard. Local citizens clamored for the Federals not to destroy the yard. A group of firebrands tried to capture the tiny sidewheel steamer Yankee, which Pendergrast had commandeered to tow Cumberland out of the Elizabeth River. The attempt failed, according to Private Daniel O’Connor of Cumberland’s Marine Guard, because when “they seized her…they let her go very quick when we pointed our pivot gun at her.” O’Connor remembered the rejected trouble makers yelling “of massacring the whole of us or taking the navy yard that night and shipping but we intended to sell our lives as dear as possible.”

Lieutenant Thomas O. Selfridge Jr. remembered a more humorous incident. One particular steamer filled with Rebels continued to hover near the yard, shouting threats and abusive language at the loyal workmen busy destroying the yard. Selfridge and members of Cumberland’s crew rigged an underwater line from the yard to a tug on the other side of the channel. When the firebrand’s tug approached the yard for another round of abuse, the hawser line was pulled taut, raking the entire length of the tug, knocking off the vessel’s smokestack, and pushing several men overboard. After this episode, there were no other attempts to approach the yard by way of the Elizabeth River.

Cumberland Escapes

Gosport Navy Yard and most of the ships stationed there began to burn when a relief expedition commanded by Flag Officer Hiram Paulding arrived aboard USS Pawnee. The Cumberland’s crew joined in this destructive work until about 4:20 a.m. when Paulding ordered all the men to the ships. Flag Officer McCauley, demoralized, was taken aboard Cumberland in tears.

The small flotilla slowly made its way with the rising tide down the Elizabeth River. Now the Federal ships crossed the obstructions sunk in the channel by Southern volunteers before dawn. “We were dragged over the obstructions,” remembered Lieutenant Selfridge of Cumberland, “and anchored off Fort Monroe.” USS Cumberland immediately became the nucleus of the Federal Blockading Squadron blocking Hampton Roads and the lower Chesapeake Bay. The sloop had left three men behind at Gosport. Lieutenant John Maury and Paymaster John DeBree had joined the Virginia Navy when Virginia left the Union. As Cumberland left Gosport, Master Tailor Albert C. Griswold jumped ship and eventually served on USS Virginia.

Active Service

After the sloop escaped from Gosport, the vessel remained in Hampton Roads as a blockader. Cumberland captured several blockade runners between April 23 and May 11, including the tug Young America and sailing vessels like the Sarah & Mary, Elite, and Dorothy Haines. The warship was then sent to Boston for minor repairs at the Charlestown Navy Yard. Of great importance was the improvement to the Cumberland’s battery. The aft X-inch Dahlgren was replaced with a 70-pounder rifle. (Note: This type of gun was not in the US Navy ordnance inventory. The rifled gun was probably a 60- or 80-pounder Parrott gun). The sloop of war was assigned to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron and returned to Hampton Roads in time to participate in Flag Officer Silas Horton Stringham’s capture of Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina, on August 28-29, 1861. USS Wabash towed Cumberland as the powerful US warships turned in a circle to shell Forts Hatteras and Clark. Cumberland then returned to Hampton Roads and was stationed with the 52-gun sailing frigate USS Congress off Camp Butler on Newport News Point.

Defending Hampton Roads

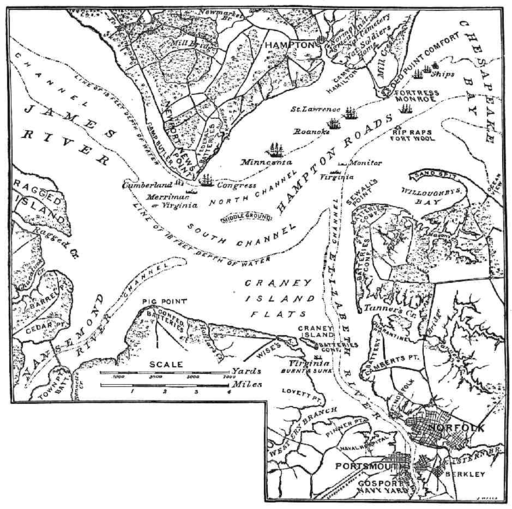

Stories about the conversion of the former USS Merrimack into the Confederate ironclad ram soon to be renamed CSS Virginia began to spread across Hampton Roads. Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, knew that the ironclad would be “exceedingly formidable” and stationed the 47-gun steam screw frigate Minnesota, the 42-gun steam screw frigate Roanoke, and the 50-gun sailing frigate St. Lawrence near Fort Monroe on Old Point Comfort where Hampton Roads emptied into the Chesapeake Bay. Two armed tugs, USS Zouave and USS Dragon, were assigned to support the two sailing warships at Newport News Point.

By March 1862, the Union anticipated the emergence of Merrimack almost any day. “Rumors of her expected appearance came so often,” Lieutenant Thomas O. Selfridge Jr. of Cumberland later wrote, “that at last it became a standing joke with the ship’s company.” The crewmen were ready for “a chance for active operations.” They had been on alert throughout the winter and drilled “until every man knew not only the duties of their station at quarters, but those of every station as well,” remembered Master Moses S. Stuyvesant of Cumberland.

While many were anxious to test the ironclad’s strength, others feared the impending attack. “She will most certainly commit great depredations to our armed and unarmed vessels in Hampton Roads,” wrote steam ram expert Lieutenant Colonel Charles Ellet. “Nothing I think,” wrote Flag Officer Goldsborough, “but very close work can be of service in accomplishing the destruction of the Merrimack.” There were concerns that the Union’s wooden warships, without the support of an armored vessel, might be unable to stop the Confederate ironclad. Goldsborough longed for USS Monitor to arrive in Hampton Roads and wrote Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, “I ask therefore if it would not be good to send the Ericsson to contend with that vessel on her own terms.”

The Eve of Destruction

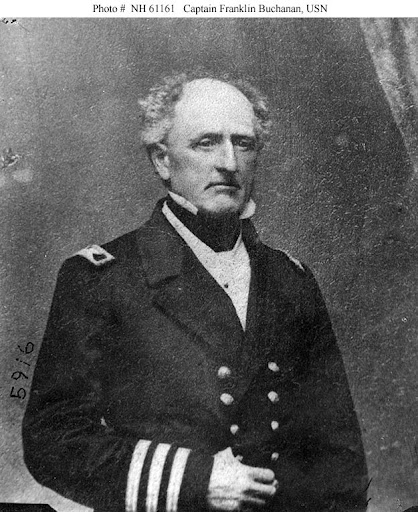

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH 61161.

A gale had blown through Hampton Roads on March 6 and 7, delaying Virginia’s plans to attack the Union fleet in the harbor. Captain Franklin Buchanan decided to take his ironclad down the Elizabeth River on a ‘shake-down’ cruise. During that voyage, Buchanan was told by Chief Engineer Ashton Ramsay that the machinery was securely braced and the engines were working beyond his expectations. Buchanan was satisfied with Ramsay’s opinion and declared, “I am going to ram the Cumberland. I am told she has the new rifled guns, the only ones in their whole fleet we have cause to fear. The moment we are out in the Roads, I’m going to make right for her and ram her.” He then called many of the crew onto the gundeck and gave them a speech with a Nelsonian flourish stating: the “Confederacy expects every man to do his duty.” According to Midshipman Hardin Littlepage, Buchanan reminded everyone that the “whole world is watching you today,” and commanded them, “Go to your guns!”

No one in the Union fleet expected the Confederates to attack that day. “The 8th of March 1862, came and a finer morning I never saw in that southern latitude,” wrote Seaman William Reblen of USS Cumberland. “The sun came up smiling in all of its splendor. It was ‘up hammocks’ that morning and then ‘holystone’ and wash decks as usual. After breakfast (it being Saturday) it was ‘up all bags’ and every old tar went through his bag mending and getting ready for the Sunday muster ‘round the capstan.’”

A Boston Journal correspondent noted: the “hours crept lazily along, the sea and the shore in this region saw nothing to vary the monotony of the scene.” He also reflected that many “a sailor might be noted, on ship board telling how much he hoped the Merrimack would show itself, and how certainly she would be sunk by our war vessels.”

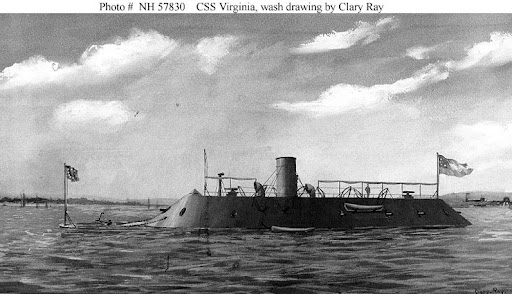

Emergence

The calm scene was quickly disrupted as CSS Virginia emerged from Sewell’s Point with two supporting armed tugs, CSS Beaufort and CSS Raleigh. The Confederate ironclad, “different from any vessel seen before,” was investigated by Zouave. “It did not take us long to find out,” noted Zouave’s Acting Master Henry Reaney, “…when we saw what all appeared to be the roof of a very big barn belching forth smoke from a chimney on fire.” The Zouave fired several shells from its 30-pounder Parrott at the ironclad and returned to Newport News Point.

“Suddenly, huge volumes of smoke began to pour from the funnels of the frigates Minnesota and Roanoke at Old Point,” Ashton Ramsay recalled. “They had seen us and were getting up steam. Bright colored signal flags were run up and down the masts of…all of the Federal fleet, Ramsay continued. “The Congress shook out her topsails, down came the clotheslines on the Cumberland, and boats were lowered and dropped astern.” Brigadier General Joseph King Fenno Mansfield at Camp Butler telegraphed Major General John Ellis Wool at Fort Monroe, “The Merrimack is close at hand.”

As the crews and officers of Congress and Cumberland readied themselves for combat, other vessels in the Federal fleet struggled to reach Newport News Point. Roanoke, her engines disabled, was taken undertow, and Minnesota got underway. Another tug was ordered to guide St. Lawrence into action. Buchanan knew that these ships would soon be brought into action. His first concern was Cumberland with its 70-pounder rifle. Littlepage recalled Buchanan’s talk with his officers en route, “He had already urged us to hurry with the work before us,” and “that is, the destruction of the Cumberland and Congress, as the heaviest of the enemy’s ships were following in our wake.”

First Shot

It took Virginia more than one hour to steam across Hampton Roads. Once within range, the Union ships and shore batteries began shelling the ironclad. The shot “had no effect on her,” as Thomas O. Selfridge recounted, “but glanced off like pebble stones.” The CSS Beaufort fired the first Confederate shot of the day at 2:20 p.m. Buchanan; however, waited until the range was less than 1,500 yards. He then ordered Lt. Charles Carroll Simms to fire the bow Brooke rifle at the Union sloop. That shell hit Cumberland at the starboard rail, showering splinters and shrapnel across the deck tumbling some Marines.

“The groans of these men,” remembered Lt. Selfridge, “the first to fall, as they were carried below, was something new” to many of the crew. The second shell fired by Simms hit just below the sloop’s forward rifled pivot gun. The gun was disabled, and the entire gun crew decimated. Dead and wounded were everywhere. “No one flinched,” Selfridge recalled, “but went on leading and firing, taking the place of some comrade, killed or wounded.” One Northern correspondent wrote that he saw “from the ship’s scuppers running streams of crimson gore.”

USS Congress

Virginia had now come abreast of Congress. The frigate fired a broadside at the Confederate ironclad, which harmlessly bounced off the iron-plated casemate. As the ironclad passed the hapless frigate, she unleashed her starboard broadside of four guns at Congress. The effect was devastating. One shell went through a gun port, dismounting the gun and “sweeping the men around it back into a heap, bruised and bleeding.” Hot shot from Lt. John Randolph Eggleston’s gun rumbled through the frigate, starting two fires, one of which threatened to ignite Congress’s powder magazine.

Virginia was armed with hot shot guns just for this purpose. They were a deadly weapon against wooden warships and were placed on board the Confederate ironclad to give it yet another technological advantage. The combination of hot shot and explosive shells was too much for Congress. The frigate was critically damaged by Virginia’s broadside; however, Buchanan did not pause to finish off the stricken prey as nothing would delay the flag officer’s intended rendezvous with USS Cumberland. “The pilot at the wheel has drawn a bead upon the Cumberland,” wrote William Norris, “and holds her true as a needle for the doomed ship.”

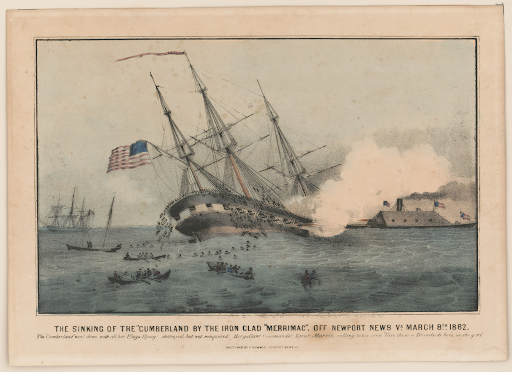

“Sink Before Surrender”

Virginia continued toward the sloop “like some devilish and superhuman monster, or the horrid creature of a nightmare.” Cumberland kept up her fire against the oncoming ironclad, but her shot “struck and glanced off, having no more effect than peas from a pop-gun.” Virginia was pounded with shot as it approached the sloop, creating a terrific din within the casemate, losing its flagstaff to enemy shot. Just before Virginia reached Cumberland, Ordinary Seaman Richard Curtis peered out a gun port and “saw a sight…all on the starboard side of the Cumberland was lined with officers and men with rifles and boarding pikes, all ready to repel us, thinking we intended to board her; I saw an officer, hat off and his sword raised, cheering on his men.” Cumberland appeared doomed as the ironclad rushed toward Virginia at almost six knots. “At her prow I could see the iron ram projecting,” Cumberland’s pilot A. B. Smith remembered, “straight forward, somewhat above the water’s edge, and apparently a mass of iron.” Smith sadly reflected, “it was impossible for our vessel to get out of her way.”

The Power of Iron Over Wood

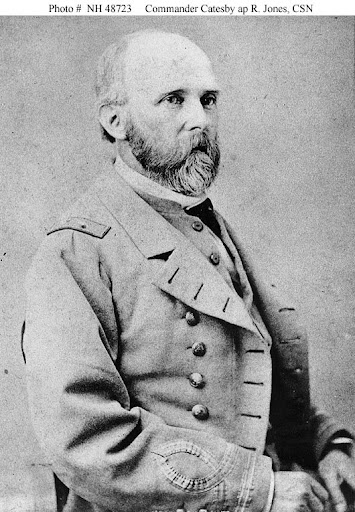

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH-48723.

“Like a huge half-submerged crocodile,” Virginia broke through the anti-torpedo obstructions and rammed the sloop on the starboard side. Executive Officer Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones recalled, “the noise was heard above the din of battle.” The 1,500-pound ram punched a hole into Cumberland’s berth deck. According to Lieutenant John Taylor Wood, the hole was “wide enough to drive in a horse and cart.” Cumberland was mortally wounded, the ramming made only worse by a simultaneous shot from Virginia’s bow rifle. Lieutenant Robert Minor would write the “crash into the Cumberland was terrific in its results. Our cleaver fairly opened her side.” Tons of water were now gushing into Cumberland, and the vessel began to sink rapidly.

“Soon, however, I heard the reports of our own guns, and then there came a tremor throughout the whole ship,” wrote Third Assistant E. A. Jack. “This is when we drove into Cumberland with our ram. Then, the cracking and breaking of her timbers told full well how fatal to her that collision was. Then, there was a settling motion of our vessel that aroused suspicion that our ship had been injured too, and was sinking.” Just before the ramming of the sloop, Buchanan ordered it to be reversed, yet there was an “awful phase,” Ashton Ramsay recalled. Virginia was caught by the weight of the sinking Cumberland as the ironclad’s engines labored to free itself. The crisis was quickly over, as the current turned the ironclad alongside Cumberland. The ram, which was faultily mounted, broke off when the weight of the stricken sloop rested upon it, and Virginia was freed. “Like a wasp we could sting but once,” Ramsay wrote, “leaving the sting in the wound.”

Lieutenant Thomas O. Selfridge later lamented that he had failed to seize the initiative to drop the sloop’s starboard anchor onto Virginia’s deck as the ironclad stood alongside Cumberland. Selfridge believed the anchor could have acted as a grappling hook, pulling the ironclad under the James River as Cumberland sank. This moment of opportunity, limited by the mounting casualties, quickly slipped away from Selfridge. Virginia’s engines finally reversed. The ram broke off, and the ironclad was freed from the sinking sloop.

March 8th, 1862. Published by Currier & Ives.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

The Change in Naval Warfare

Buchanan now positioned the ironclad parallel to Cumberland, and the next half hour, they exchanged cannon fire. Both ships were engulfed in smoke as Cumberland sent several broadsides into Virginia at a range of fewer than one hundred yards. Selfridge was “fighting mad when I saw were producing no effect upon the iron sides of the Merrimac.” Unbeknownst to the Union crew, the sloop inflicted severe damage to Virginia. “She did us more damage than all of the rest of the fleet and batteries,” noted Ashton Ramsay, “…put together.” When Virginia rammed the sloop, the ironclad was struck by a tremendous broadside from Cumberland. Richard Curtis, a member of the bow rifle crew, recalled, “as the gun recoiled back …then Brave {Charles} Dunbar…a good friend…jumped over the breechin, threw his head partly out of the port and was instantly killed…he fell at my feet.”

A shell struck the port sill and sent fragments inside Virginia, killing two men and wounding several others. The ironclad’s smokestack was riddled by this broadside. The damaged funnel caused the gundeck to fill with smoke and caused the steamer to lessen its speed. One shot cut the anchor chain, which whipped inboard, wounding a few more men. Cumberland’s three broadsides swept away Virginia’s starboard cutter, guard howitzers, stanchions, and iron railings. Two of the Confederate ship’s guns had their muzzles shot off, killing one and injuring others. Sharpshooters fired into Virginia’s open ports, wounding two men. While there was little damage to the iron casemate, Catesby Jones noted that had the sloop’s guns “been concentrated at the water-line we would have been seriously hurt, if not sunk.”

Virginia’s sloped sides, coated with grease to help deflect shot, began to crackle and pop from the heat and the flames caused by exploding shells. Midshipman Littlepage wrote that the ironclad seemed to be “frying from one end to the other.” He overheard an exchange between crew members Jack Cronin and John Hunt: “Jack, don’t this smell like hell?” “It certainly does and I think that we will be there in a few minutes.”

It was indeed hell on Cumberland. Master Moses S. Stuyvesant remembered it as a “scene of carnage and destruction never to be recalled without horror.” “The shot and shell from the Merrimack crashed through the wooden sides of the Cumberland as if they had been made of paper,” remembered Acting Master’s Mate Charles O’Neil, “carrying huge splinters with them and dealing death and destruction on every hand.” O’Neil was spattered with the “blood and brains” of Master’s Mate John M. Harrington when a shell whizzed past. He remembered how “Cumberland’s once clean and beautiful deck was slippery with blood, blackened with powder and looked like a slaughterhouse.”

“Give Them a Broadsides, As She Goes!”

Lieutenant George Upham Morris, Cumberland’s executive officer and acting commander, strove to save the Union vessel. Command of the sloop fell upon Morris on March 8, 1862, because its captain, William Radford, was assigned to court-martial duty aboard USS Roanoke. Radford rushed to his ship on horseback when Virginia entered Hampton Roads but arrived too late. Meanwhile, Morris attempted to turn Cumberland on her anchor cable to either bring more guns into action or cut the cable to save the ship by running her around. It was too late, as water had already reached Cumberland’s berth deck. The ship was doomed. About 3:35 p.m., Morris gave the order to abandon ship, extorting the remaining crew members: “Give them a Broadsides boys, as She goes!” “She went down bravely, with her colors flying,” Catesby Jones remembered. Cumberland’s masts protruded above the waves, the flag marking the spot where 121 Union sailors perished.

The Flag Still Flies

Cumberland’s flag still hanging from the sunken sloop’s mast sent a chilling message to the rest of the Federal fleet in Hampton Roads. Virginia, however, had not finished its destructive work for the day. The Confederate ironclad slowly turned about and sank USS Congress and two transports, captured a schooner, and damaged the tug Zouave and the frigates Minnesota and St. Lawrence. With 247 casualties, it was the worst US Navy defeat until Pearl Harbor, 88 years later.

Only darkness and a receding tide had stopped Virginia from inflicting more damage on the Union warships. They seemed powerless to defend themselves against the return of Virginia. When the Confederate ironclad had rammed and sunk USS Cumberland, the ironclad had proven the power of iron over wood. It was considered a super-weapon destined to control the American coastline. Lieutenant Robert Minor, flag lieutenant of Virginia, expressed that it was “a great victory. The Iron and the heavy guns did the work.” Despite the Confederates rejoicing, their tactical control of Hampton Roads was short-lived. The next day, CSS Virginia dueled to a standstill with the Union ironclad, USS Monitor. Iron now ruled the waves.

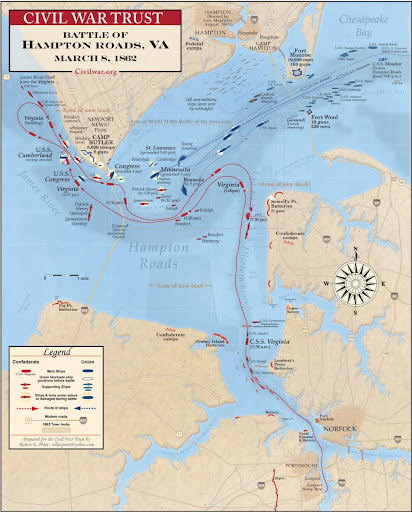

Courtesy of American Battlefield Trust: https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/hampton-roads-march-8-1862.

Source: John V. Quarstein, USS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2012.

Read more about the capture of Hatteras Inlet here: https://www.marinersmuseum.org/2021/09/the-capture-of-hatteras-inlet/