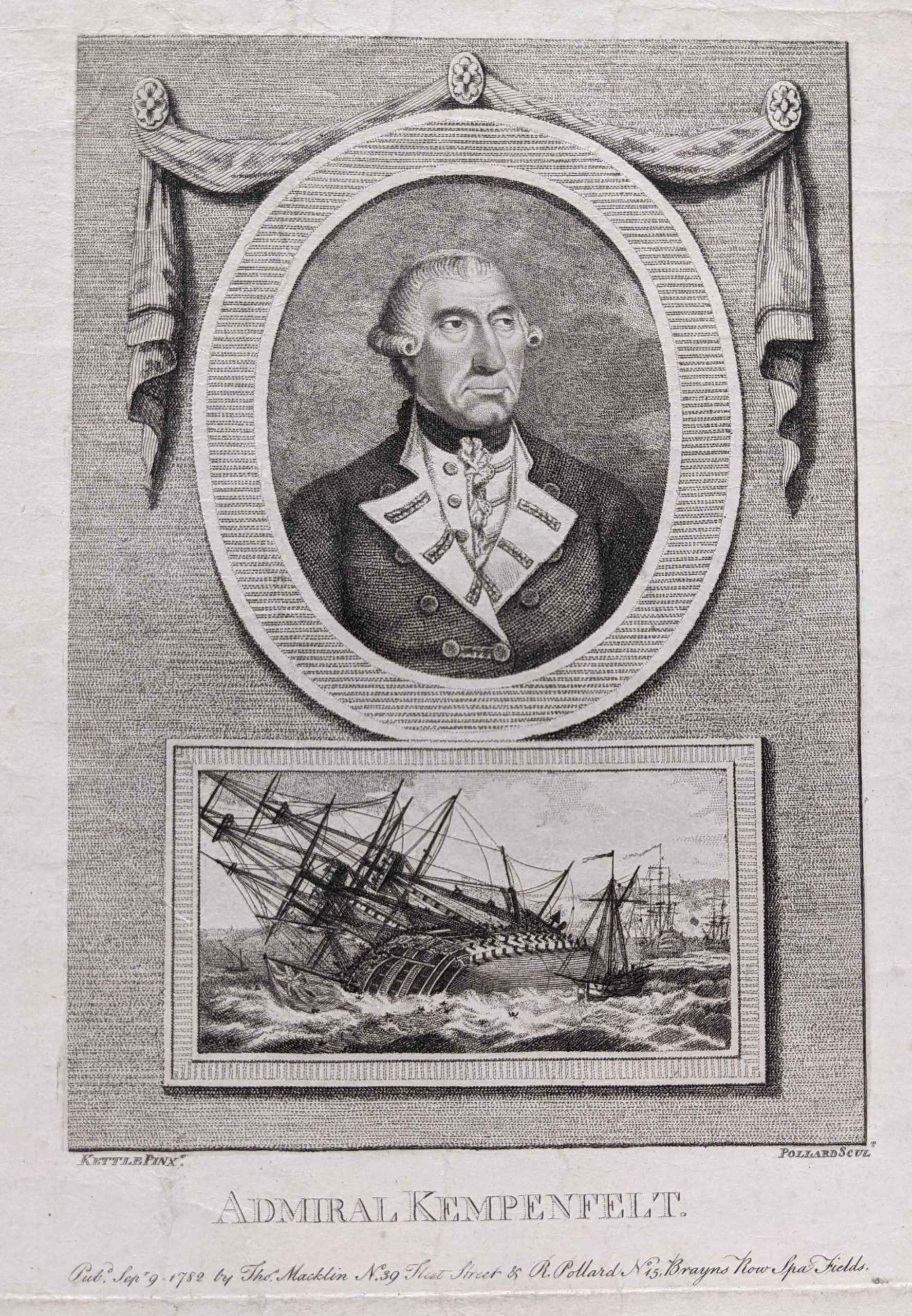

August 29 marked the 239th anniversary of one of the Royal Navy’s worst and most unnecessary disasters–the capsizing of the 108-gun first rate ship HMS Royal George. When the disaster occurred there were innumerable family members, merchants and other people on board visiting the crew. As a consequence, there were wide discrepancies in the number of reported fatalities. Most believe somewhere between 500 and 1400 men, women and children died in the capsize–including one of England’s most respected admirals, Richard Kempenfelt.

HMS Royal George was built between 1747 and 1756 at Woolwich Dockyard. She was a ship of new design and at the time of her launch was the largest warship in the world. Although she spent many years “in ordinary” (which means laid up waiting for action) between the Seven Years’ War and American Revolutionary War, Royal George frequently served as an admiral’s flagship.

Sixty-four year old rear admiral Richard Kempenfelt joined Royal George in April of 1782. The British and French were still embroiled in the American Revolutionary War so by early May, Kempenfelt, commanding seven ships-of-the-line, had sailed from Spithead (Portsmouth, England) to patrol the English Channel. Interestingly, by the end of the month his little fleet was being ravaged by an influenza pandemic that started in Germany in the spring of 1782 but “took its origin in the Far East, probably in Imperial China.”1 Luckily the epidemic passed quickly and Kempenfelt’s ships were back on patrol by the end of June. On the morning of August 14th, Royal George joined Admiral Lord Howe’s fleet at Spithead to begin preparations for a voyage to relieve Gibraltar which was being blockaded by the French and Spanish.

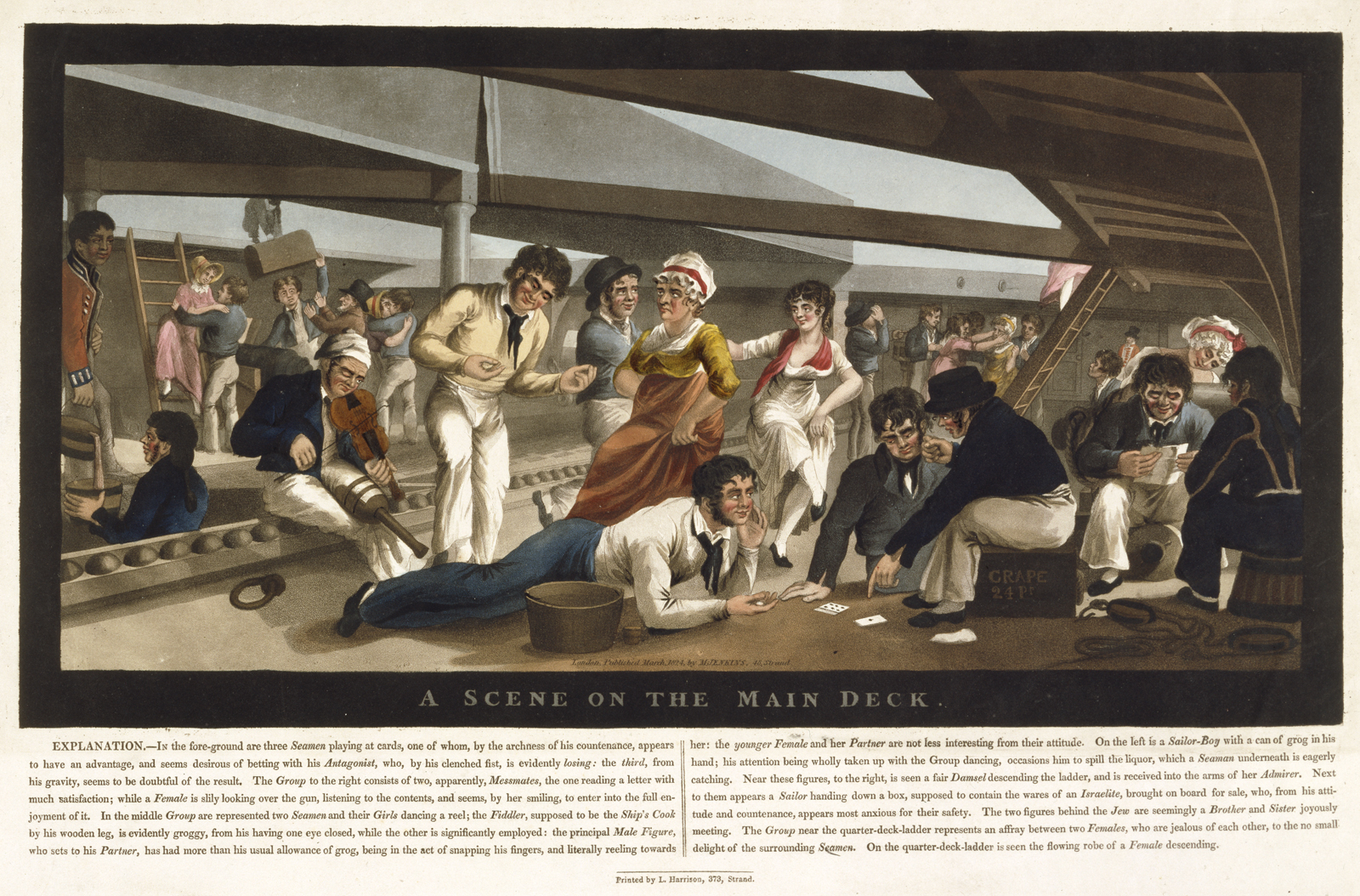

While anchored at Spithead, Royal George’s carpenter, Thomas Williams, learned that the pipe that filled a saltwater cistern in the hold (used to wash the lower gun decks down) was clogged and recommended replacing it. Since they couldn’t put the ship in dry dock (sailing orders for Gibraltar were imminent) and someone wasn’t willing to wait, it was decided to give the ship a “parliament heel”. This means the shot and cannon were moved over to one side in order to lean the ship over just enough to expose the area where the pipe was located. Unlike careening, which occurs in shallow water, a parliament heel occurs in deep water.

One of the men notified about the repair work was William Nichelson, the master attendant of Portsmouth Dockyard. Nichelson immediately registered his concerns about the repair work with Admiral Kempenfelt, who was a close friend. “Yes,” Nichelson conceded, the ship had been given a parliament heel in the past without suffering any ill effects but this time the situation was different. First, Royal George was heavily loaded with provisions for her upcoming voyage so she sat much deeper in the water. Nichelson also felt a parliament heel would place too much stress on Royal George’s aging frame which might cause some sort of structural failure. His greatest concern lay in the manner in which the ship was to be heeled over and, as it turns out, his concern was valid.2

Although Nichelson believed he had convinced Kempenfelt to postpone the work on the morning of August 29th the repair work moved forward as planned. The weather was calm and the ship was anchored midway between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight in about 84 feet of water. To heel the boat, all of the guns on the port side were run out, including the lower deck guns, while the lower deck guns on the starboard side were run in as far as their breechings would allow. When carpenter Williams complained the amount of heel wasn’t enough, the ship’s captain, Martin Waghorn, ordered the shot and a few additional guns on the middle and upper decks to be shifted as well. The amount of shifted metal was roughly 131 tons which heeled the ship over about 8.75 degrees.

To complicate matters, victualling vessels had begun arriving shortly after dawn with additional provisions for the ship’s upcoming voyage. Thus, while the ship was heeled, additional provisions including ship’s biscuit, flour, beer, water and possibly rum were being actively loaded onto Royal George’s decks. While the repair work and victual unloading progressed, the chop typical of Portsmouth harbor’s flood tide rose to such an extent that the bobbing of the victualing vessel Lark, which was lashed alongside Royal George, began driving spray into two of her open lower gun ports (which gives you some idea of how close they were to the water). The ports were closed but weren’t fully secured to make them waterproof (nor were any of the other lower deck ports!).

Reading witness testimony, it seems the officers and crew didn’t recognize the peril they were in until it was too late. About twenty minutes before the disaster a quarter gunner named William Murray noticed that “above fifty tons” of water had collected in the portside scuppers (outlets that helped drain sea and rainwater overboard–which should have been plugged before the repair work was undertaken!). So unconcerned were the men that some were light-heartedly chasing mice flushed out of their hiding places by the rising water while another was unconcernedly swirling two small boys around in a tub in the accumulating water.

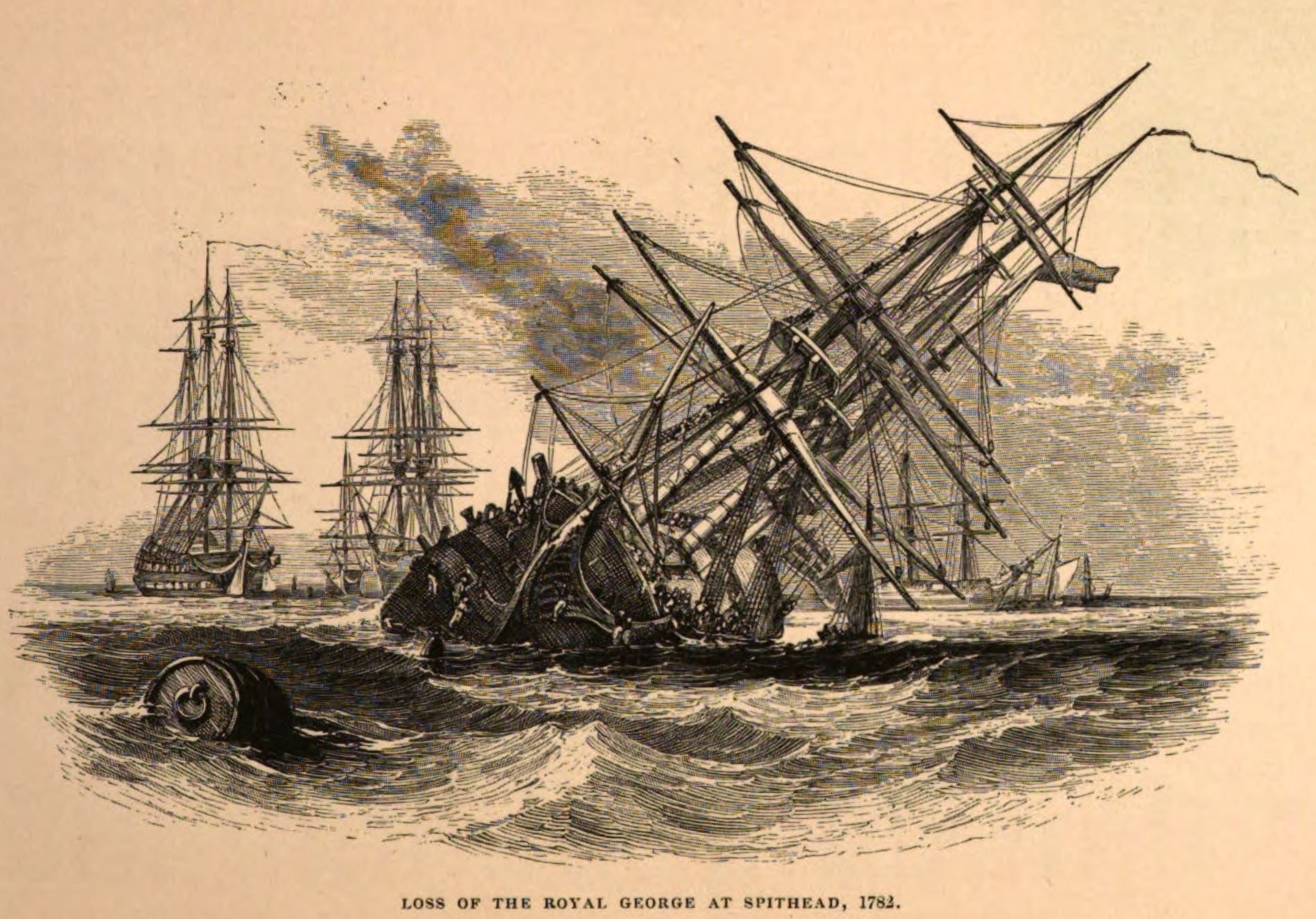

Finally, when it was reported to carpenter Williams that at least 32 inches of water had accumulated in the ship’s hold, concern that the ship was “settling” was raised. Around the same time the ship’s master, Richard Searle, arrived on board from visiting his wife frantic about the precarious position of the ship (which he had seen from a boat on the water). Although the crew were immediately given the order to right the ship, it was too late. The rush of men to their stations destabilized the ship even further and water began pouring in through every port.

At this point everything was complete pandemonium. People raced for the open starboard ports, but as the ship continued its death roll the open ports became inaccessible. While most people trapped inside the hull probably drowned, the evidence shows some were killed by shifting cargo and cannon. Many of those that did escape drowned because they didn’t know how to swim while some of those that did were drowned by non-swimmers struggling to stay afloat or by the downward suction created by the sinking ship. Within moments the only part of Royal George visible were the tops of her masts. Many of those that did survive did so by clinging to this exposed rigging or to rolled hammocks that floated free of the wreck.

According to Admiral Howe, 331 officers and crew survived. This number includes quite a few that weren’t on board the ship when the disaster occurred.3 It also doesn’t include men who may have been pressed into service and used the opportunity to desert. Only a handful of the approximately 300 women on board survived and only one of the estimated 60 children on board survived.4 As for Admiral Kempenfelt, he appears to have died trapped in his cabin.

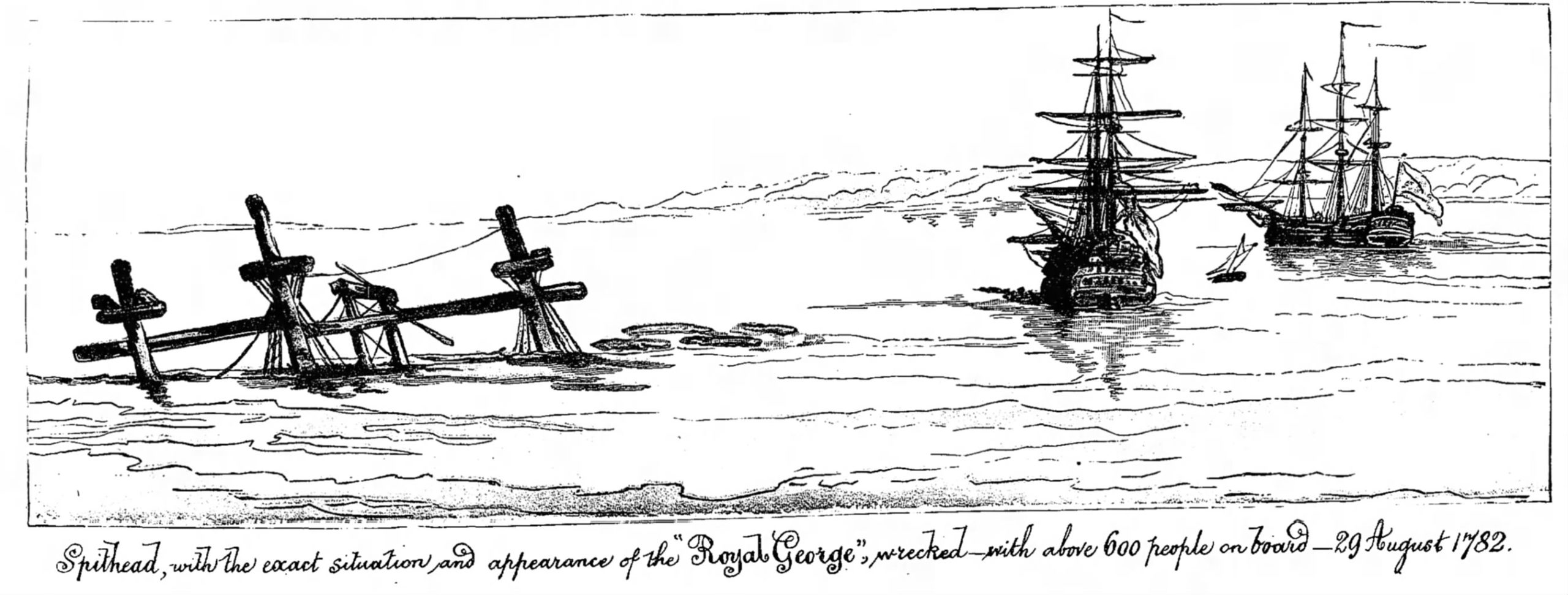

So there she lay. Once one of the proudest vessels of the Royal Navy, the Royal George was now a mass grave, a menace to shipping and a VERY visible reminder of the apparent ineptitude of the ship’s officers.5 As you would expect, the Navy wanted the ship removed from the bottom of the Solent immediately.

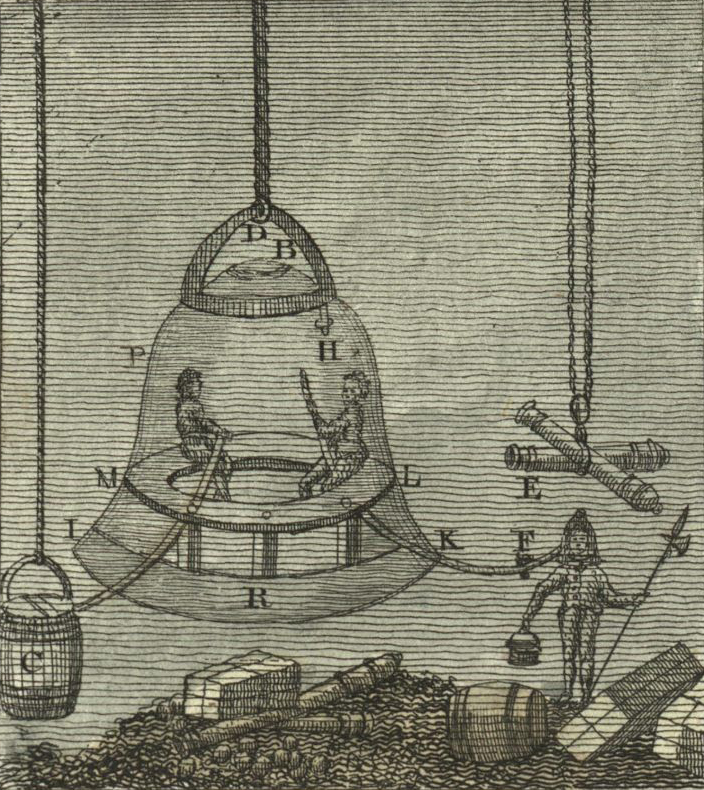

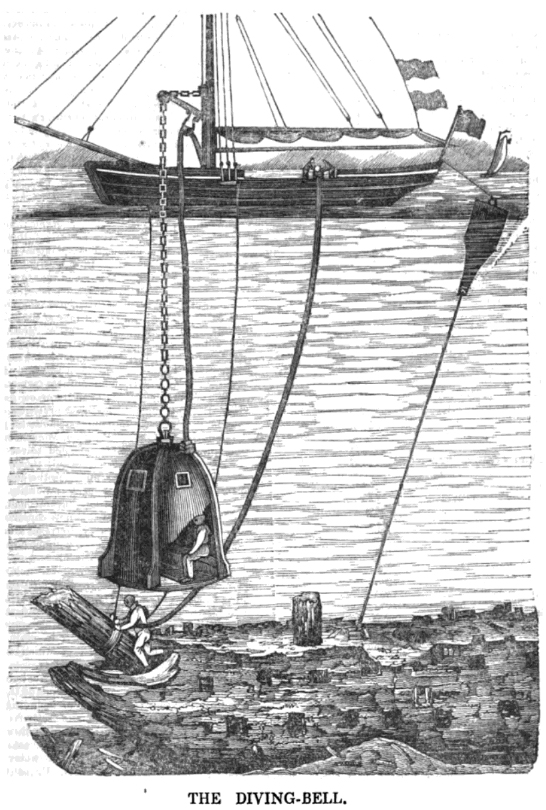

About a week after the sinking, surgeon Thomas Spalding and another man visited the wreck several times in a diving bell designed by Dr. Edmund Halley. In October and early November, his brother Charles used the diving bell to recover nine brass and six iron guns. On clear days, Spalding said he could see corpses “in various attitudes” and that others were clinging to or trapped beneath guns and gun carriages. [Removing and honoring the dead? Not interested. It didn’t make him or the Navy any money.]

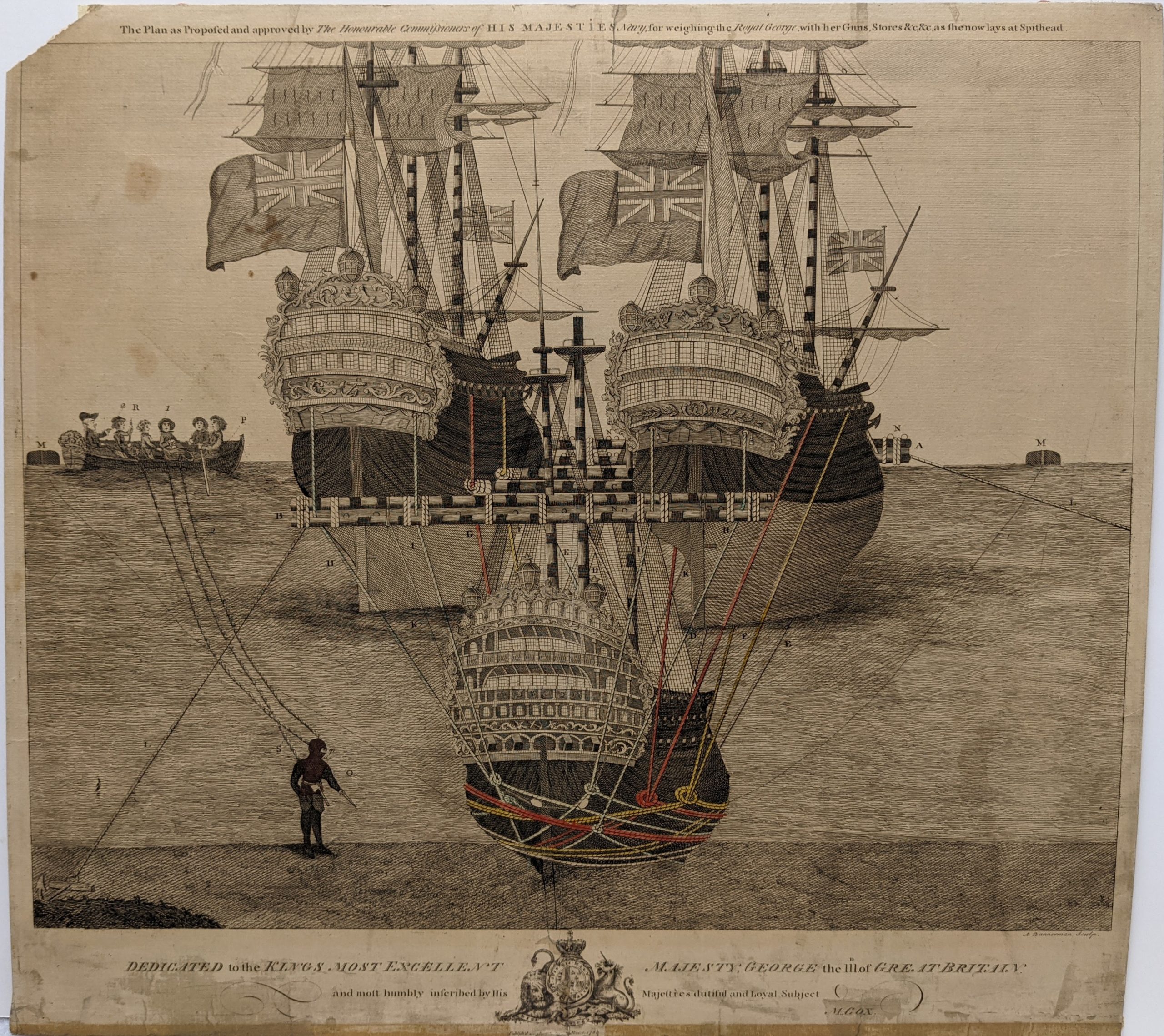

By October, the Admiralty was being bombarded with proposals to recover the ship or salvage its guns. The plan they chose was the second submitted by shipbroker William Tracey who proposed to wrap the hull in slings of chains and cables and attach them to a raft lashed between two lighters. The idea being that if the attachment was made at low tide as the tide rose so too would the Royal George. Then the raft, lighters and Royal George could be towed to shallower water. Then the process could be repeated until the ship could be pumped out and refloated. It did work to a certain extent–Tracey managed to move the hull thirty or more feet–but his efforts were continually hindered by the weather and enormously uncooperative Dockyard officials.6

The next attempts to deal with the wreck came in 1834 when a man named John Deane, who had worked with Augustus Seibe to devise a diving suit that enabled him to work under water. Over three years, Deane recovered 18 bronze 24-pound cannons, three bronze 12-pound cannons, and seven iron 32-pound cannons from the wreck.

The task of clearing the wreck once and for all was given to Colonel Charles Pasley, now known as the father of the Royal Engineers. His method of wreck removal was a little different, it involved underwater explosives–lots of them! Between 1839 and 1843, Pasley led a contingent of Royal Sappers and Miners from Chatham to systematically blow up and clear the wreck.

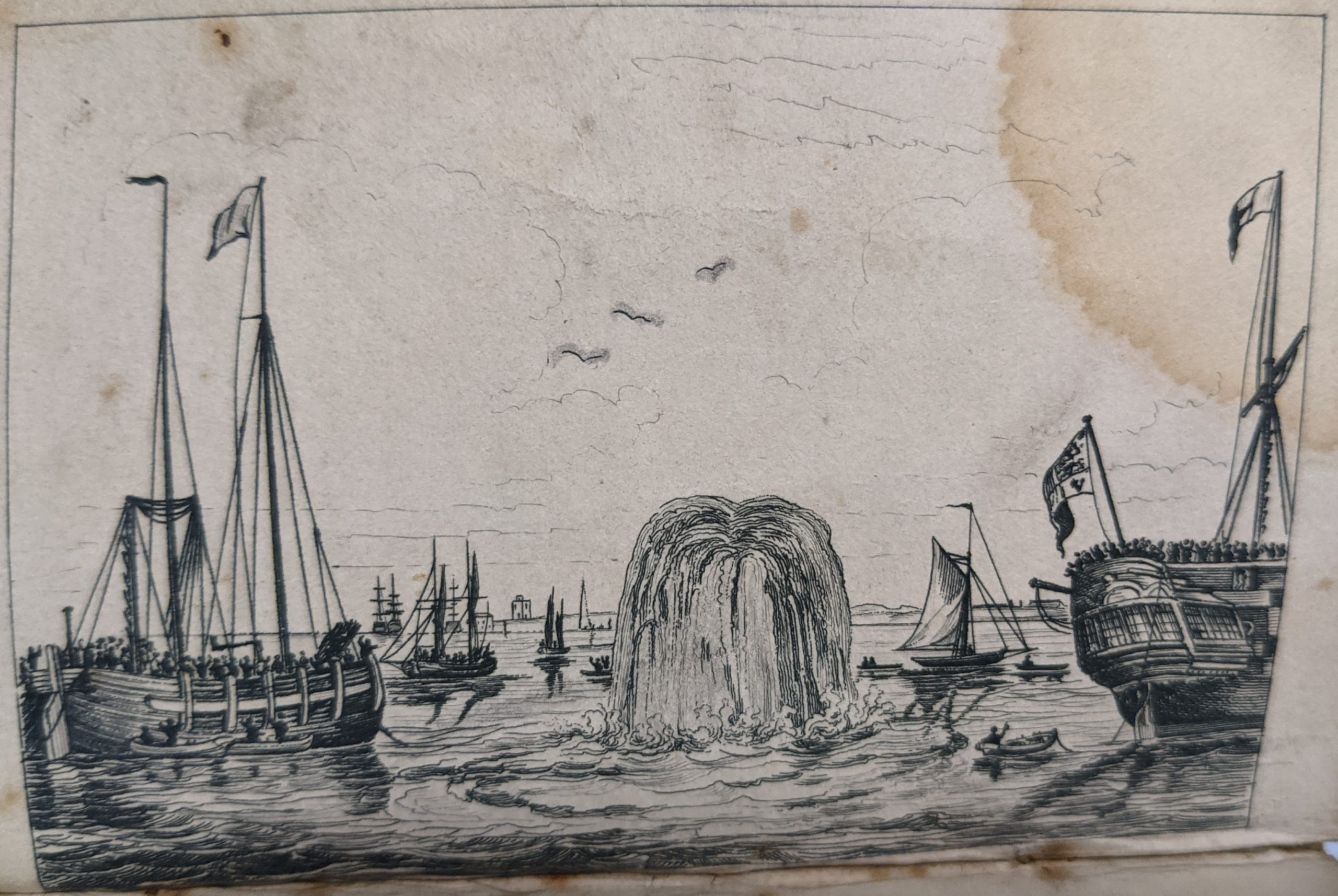

The first successful explosion occurred on August 29, 1839, the 57th anniversary of the disaster. Impatient with the results, on September 23rd Pasley laid a 2,320lb charge against the starboard hull amidships. The subsequent explosion caused a sharp shock “like an earthquake” that was followed by a rising dome of water not less than 25 to 30 feet high. With each successive explosion, bigger and bigger as time went on, divers were able to bring guns and other items, including human remains, to the surface.

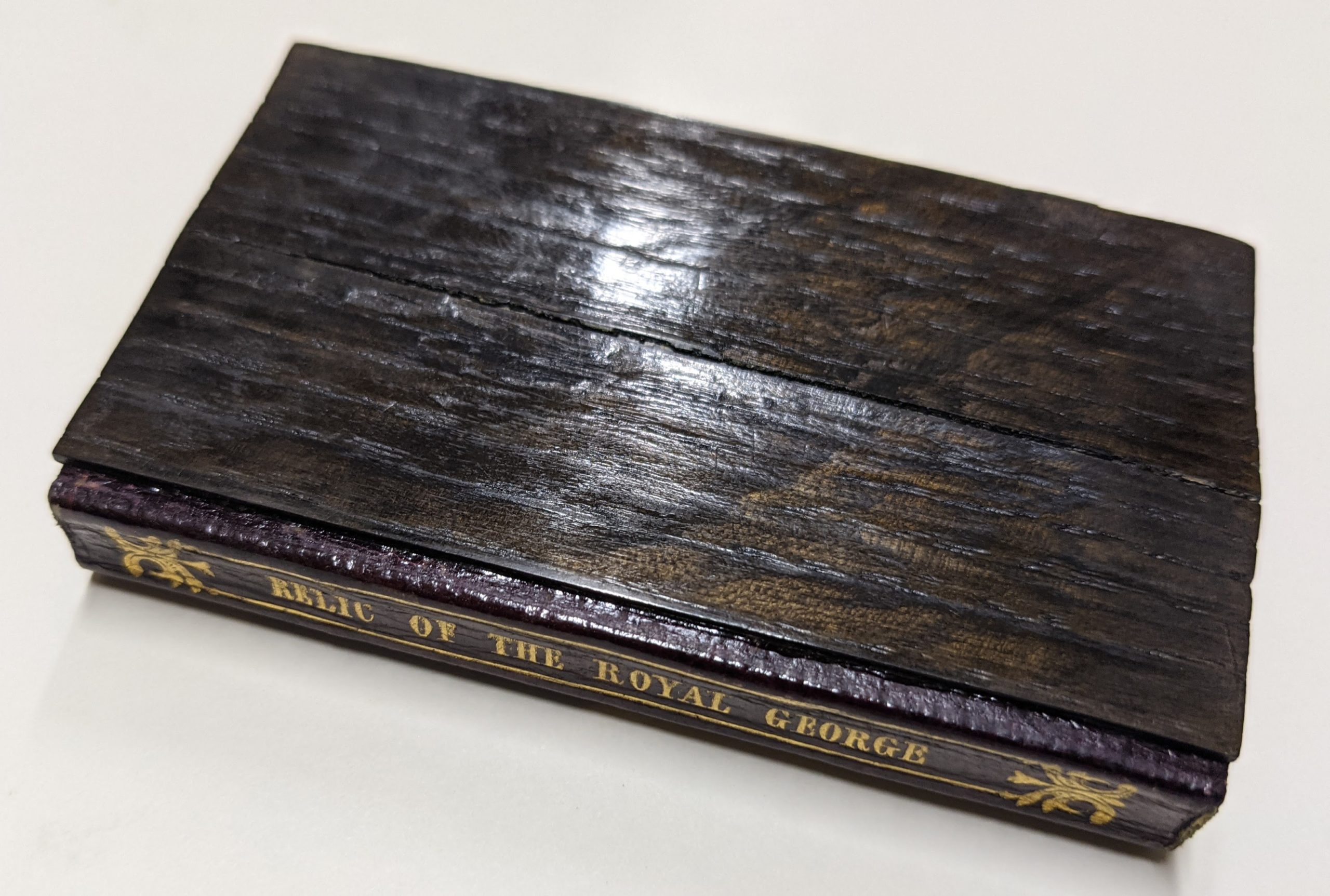

Many items recovered from Royal George grace the collections of museums in England and around the world. At Mariners’, we are lucky to hold three publications documenting the loss and removal of Royal George that are covered with wood recovered from the wreck by Colonel Pasley’s crews. We also have a small silver medallion that may have been made by one of the survivors.

Want to learn more? Check these books out:

The Royal George by Brigadier R. F. Johnson, published by Charles Knight & Co. Ltd in London, 1971.

Catastrophe at Spithead: The Sinking of the Royal George by Hilary L. Rubenstein

Footnotes:

1“The Influenza Pandemic of 1782, with special reference to its occurrence in the Imperial City of Nuremburg” by Manfred Vasold. Würzburger Medizinhistorische Mitteilungen, 2011, 30: 386-417.

2While Nichelson would have preferred waiting to conduct the repair work until the ship could be dry docked, he felt a safer method of heeling the ship was to hang casks of sea water from every point on the port side where tackle could be affixed. Doing this would enable the ship to be righted quickly in an emergency (by simply cutting the casks away). This, of course, was enormously labor intensive which is probably why the easier method of moving the guns was used.

3Approximately 74 officers, crew and marines were on shore when the disaster happened leaving just 251 survivors. The muster taken on the Saturday before the disaster showed 821 officers and men on board.

4A little boy named Jack managed to survive by clinging onto a sheep that remained swimming long enough for the boy to be rescued. Some say that only a single woman survived.

5Yes, the Court Martial that occurred afterwards found everyone innocent and blamed the incident on a rupture of the ship’s rotten hull, but later efforts to recover the ship showed that this simply wasn’t true. And let’s be honest, wasn’t sending 821 men to sea in a ship known to have a mostly rotten frame equally stupid?

6Colonel Charles Pasley was convinced that Tracey’s plan would have worked if he had been given the assistance the Navy had promised. In fact, the Navy used his method several times to raise sunken vessels.