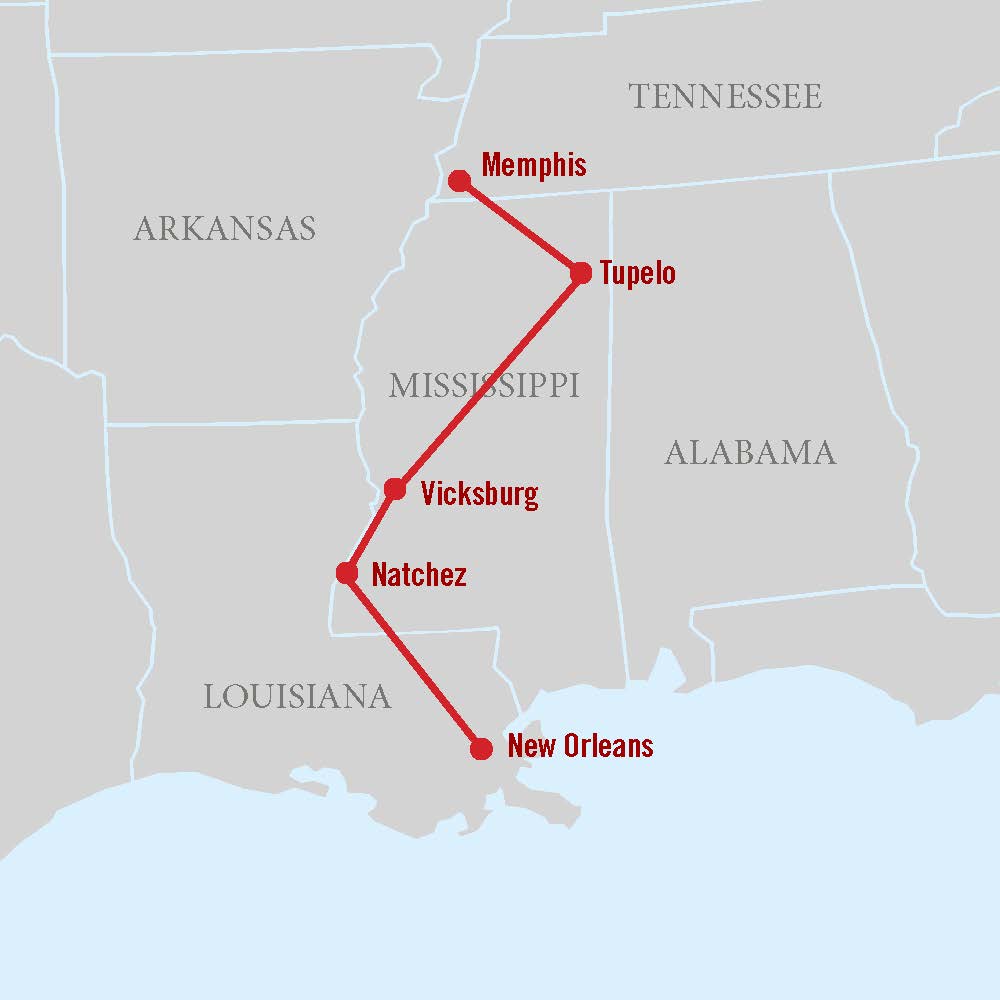

Complete control of the Mississippi River Valley was a key war aim for North and South alike. It was critical for the Confederacy to defend the Mississippi from Union attack to protect significant agricultural resources and manufacturing centers. Likewise, the Union needed to open the river to the sea to maintain the commerce of the Midwest. This contest along the ‘father of all rivers’ was a tremendous struggle. Victory would be achieved with new and improved ship designs and industrial superiority.

RIVER DEFENSE FLEET

The Confederates rushed to build fortifications to defend important river ports along the Mississippi; however, more was needed. This resulted in the creation of the River Defense Fleet and the construction of several ironclads. The quickest way for the Confederates to build a fleet was by acquiring various steamers in the vicinity of New Orleans. Many of these ships were constructed in Algiers, Louisiana, and Cincinnati, Ohio.

Major General Lovell Mansfield, a West Point graduate, was authorized by Confederate president Jefferson Davis to transform 14 merchant vessels into warships. Each vessel was to be fitted out as a ram. Modifications included strengthening each ship’s bow by filling the bow’s interior with solid oak, planking over the forward 20 feet with oak sheathing, and covering this section with one inch of railroad iron.

Double bulkheads protected the engines. The inner bulkhead was made of 12 inches of pine beams. The outer bulkhead was plated over with one-inch railroad iron. The 22-inch wide space between the bulkheads was packed with compressed cotton, resulting in many of the rams being called cottonclads. [1]

CONFEDERATE IRONCLAD CONSTRUCTION

The Confederates developed an ambitious ironclad construction program to defend the Mississippi River. Two ironclads, Louisiana and Mississippi, were laid down at New Orleans. Another two, Tennessee and Arkansas, were under construction at the former Memphis Navy Yard, then operated by J.T. Shirley; and another, the Eastport, was under construction near Cerro Gordo, Tennessee.

Only CSS Arkansas was not scuttled or captured by May 1862. This left the Confederates reliant on the rams of the River Defense Fleet to defend New Orleans and the forts along the river bordering Tennessee. The defenses like Fort Pillow protecting the manufacturing center and river port of Memphis needed support from ships.

The River Defense Fleet was split into two components. John A. Stephenson commanded six of these rams during Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut’s attack on Forts St. Philip and Jackson. All of these River Defense Fleet ships were destroyed. The rest were taken upriver to arrest the advance of the Union gunboats. [2]

WESTERN GUNBOAT FLOTILLA

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LOT 14043-2, no. 1212 [P&P].

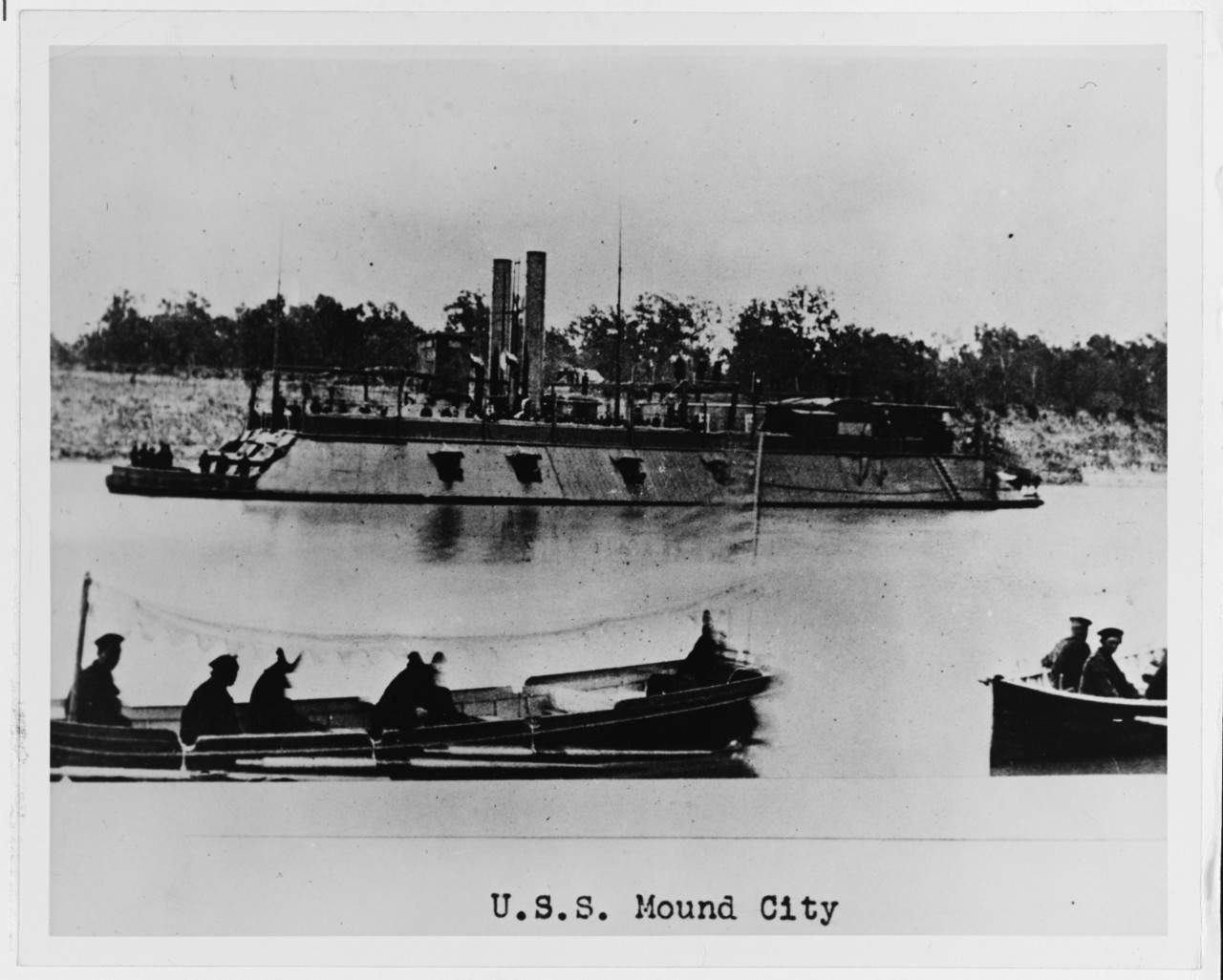

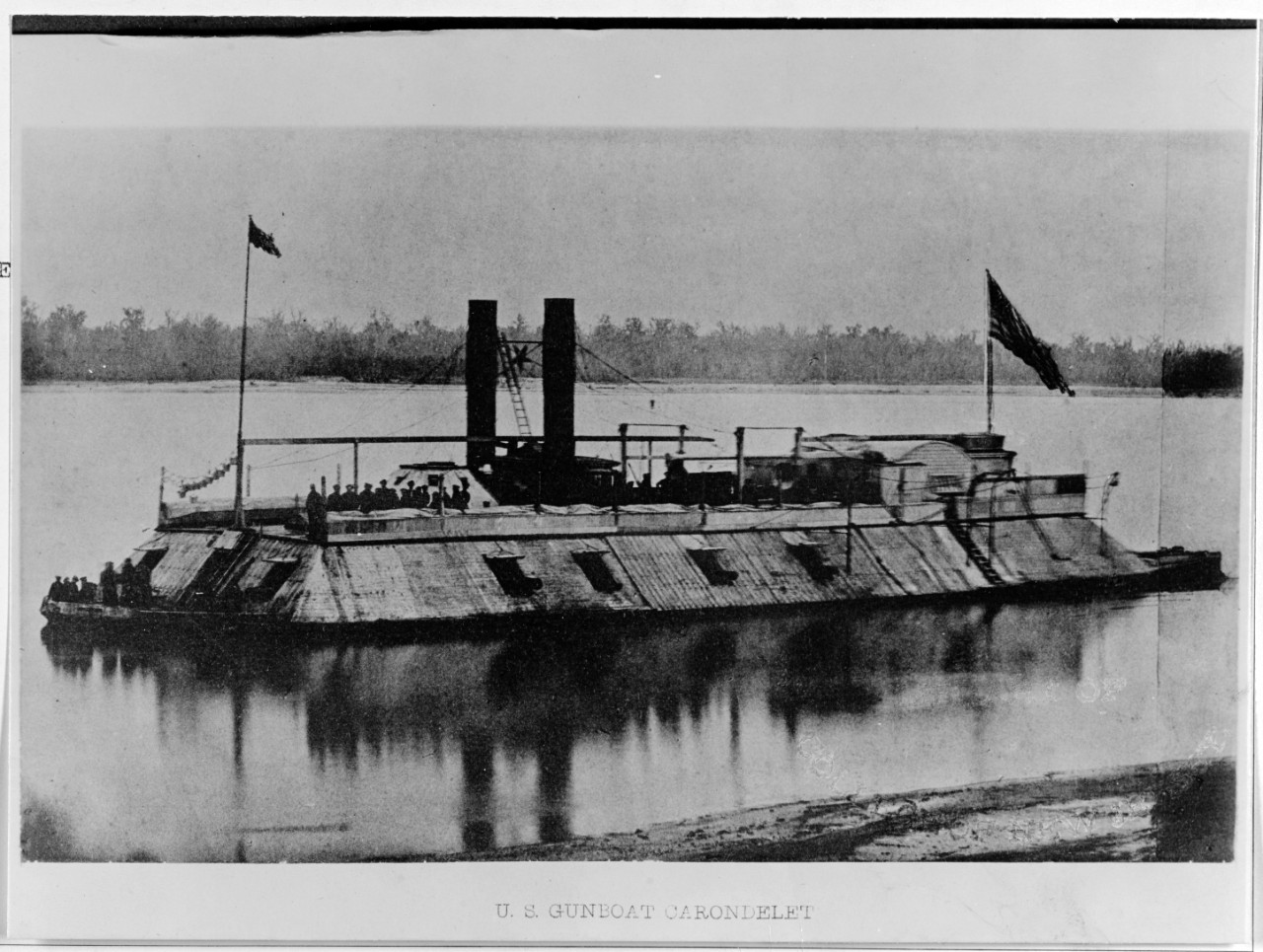

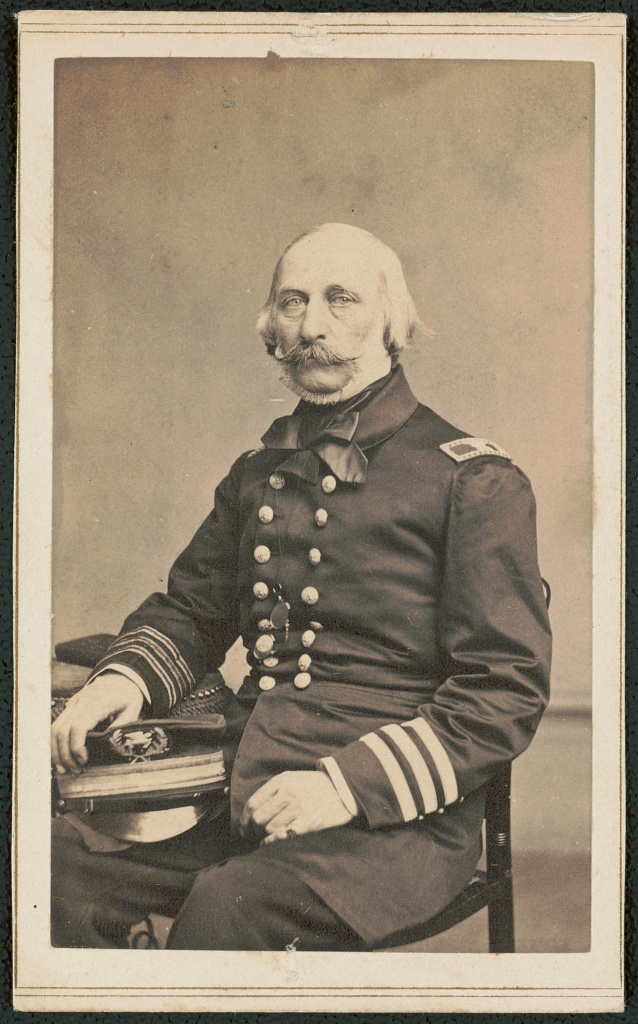

Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote’s wound received during the attack on Fort Donelson prompted him to request leave to convalesce. Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis replaced him. A graduate of Harvard, Davis spent most of his career completing scientific work. He was a member of the Blockade Strategy Board as well as the Ironclad Board. Davis had no previous combat experience other than serving as Flag Officer Samuel F Dupont’s chief of staff during the capture of Port Royal Sound, South Carolina. Eventually, Admiral Farragut requested Davis be replaced as he considered him more a scholar than a sailor.[3] The command Davis inherited included the timberclads Lexington, Tyler, Conestoga, and several city-class casemated ironclads, including Mound City, Cincinnati, and Carondelet. [4]

THE GENIUS OF CHARLES ELLET JR.

Lives and Works of Civil and Military Engineers of America.

New York: D. Van Nostrand. opp. p. 257.

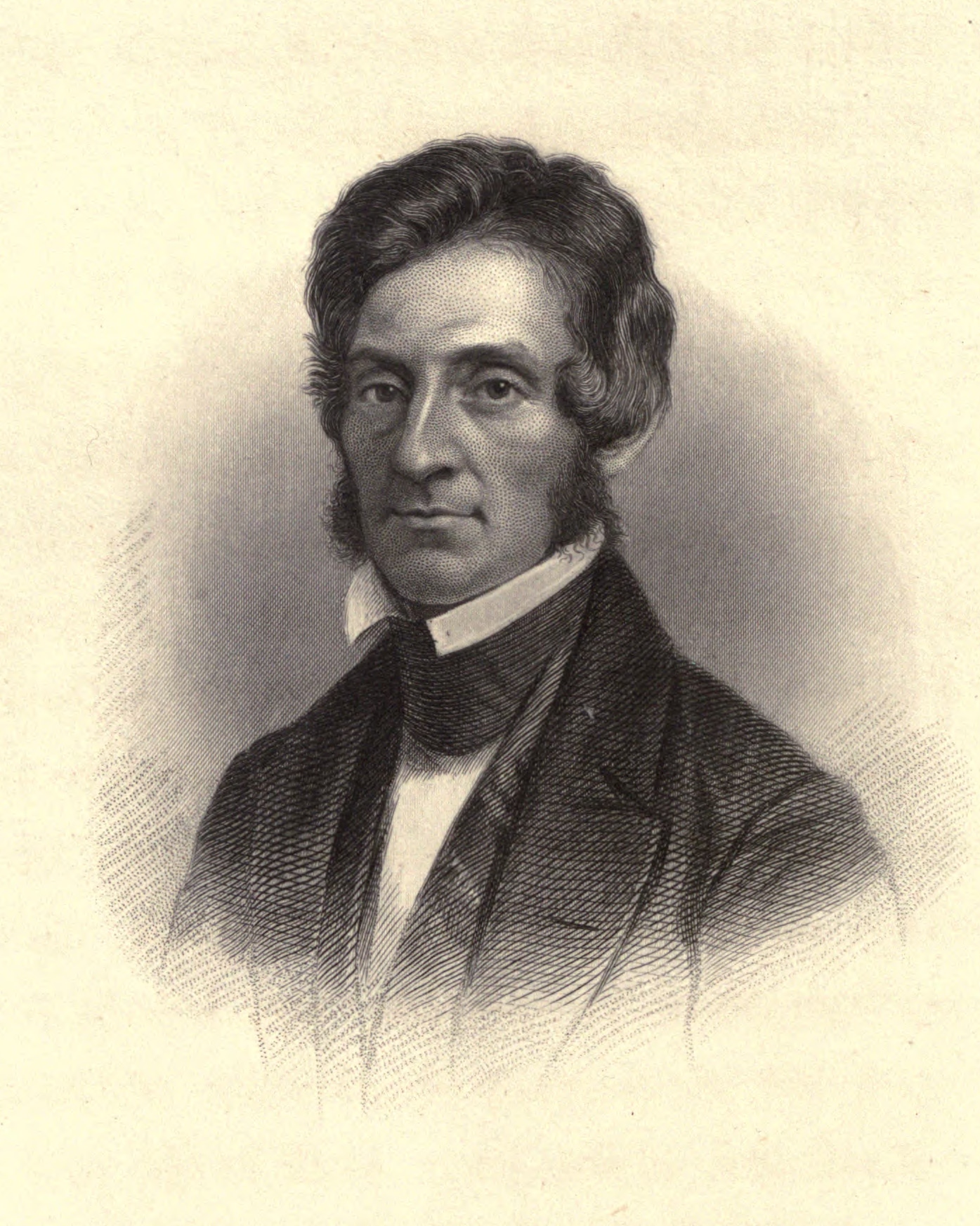

In addition to these ironclad and timberclad warships, a separate command component of rams was added to support the Western Gun Boat Flotilla activities. The US Ram Fleet was the brainchild of Charles Ellet Jr., a prewar engineer noted for his work on railroads like the Utica Schenectady Railroad, canals like the James River and Kanawha Canals, and the construction of suspension bridges.

In 1848 he built the longest wire-cable suspension bridge over the Ohio River at Wheeling, West Virginia. In 1850, the Secretary of War contracted Ellet to prepare a plan for improving flood control along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. His publication, Report Of The Overflows Of The Delta Of The Mississippi, resulted in major improvements to the New Orleans waterfront.[5]

RAM FEVER

Charles Ellet learned about the 250-ton SS Vesta’s ramming and sinking of the 2,794-ton SS Arctic on September 27, 1854. This incident reminded him of the ramming tactics of ancient Roman and Greek galleys. Ellet approached the Russian and US navies about the development of ram warships but was rebuffed. In 1855, he published a pamphlet, Coast And Harbor, Or The Substitution Of Steam Battering For Ships Of War, to garner support for his concept. [6]

Ellet’s theories were ignored until March 8, 1862, when the ironclad CSS Virginia rammed and sank USS Cumberland. The federal government quickly recognized this new technique of naval warfare and knew the Confederacy was building rams on the Mississippi River. So, in March 1862, Secretary of War Edwin W. Stanton appointed Ellet colonel and authorized him to form the US Ram Fleet to serve on the Mississippi.

The intrepid Ellet quickly acquired nine fast steamers and converted them into rams. He strengthened each ram with a timber bulkhead 12 to 16 inches wide and 4 to 7 feet high, running from bow to stern. They had iron tie rods arranged to prevent the hulls from spreading, and iron stays to stabilize their engines.

Ellet’s rams seemed the right solution to counter the Confederate rams; however, the US Ram Fleet was a separate command from the Western Gunboat flotilla. Ellet reported directly to the Secretary of War – a troublesome arrangement. [7]

CONFEDERATE COMMAND STRUCTURE

The Confederate River Defense Fleet had a nominal commander, riverboat captain James E Montgomery; however, Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson, Missouri State Guard, also claimed command. It did not matter who had the overall command as every captain, except Thompson, had no military experience and acted on their own during each engagement. Without unity of command, the River Defense Fleet simply had no coordination.[8]

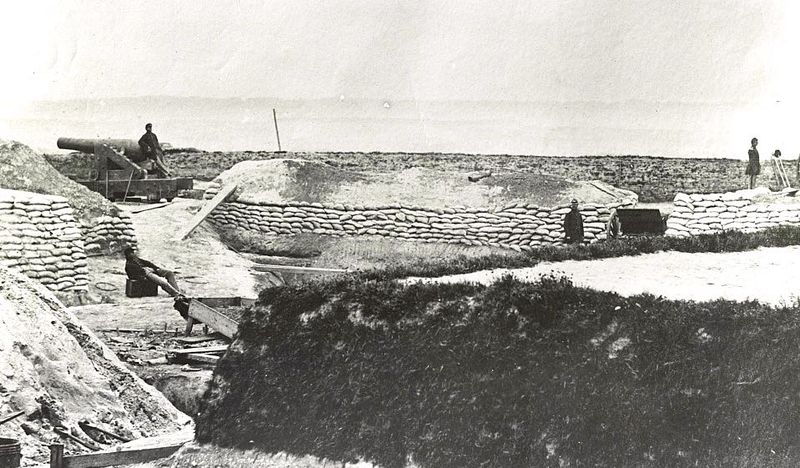

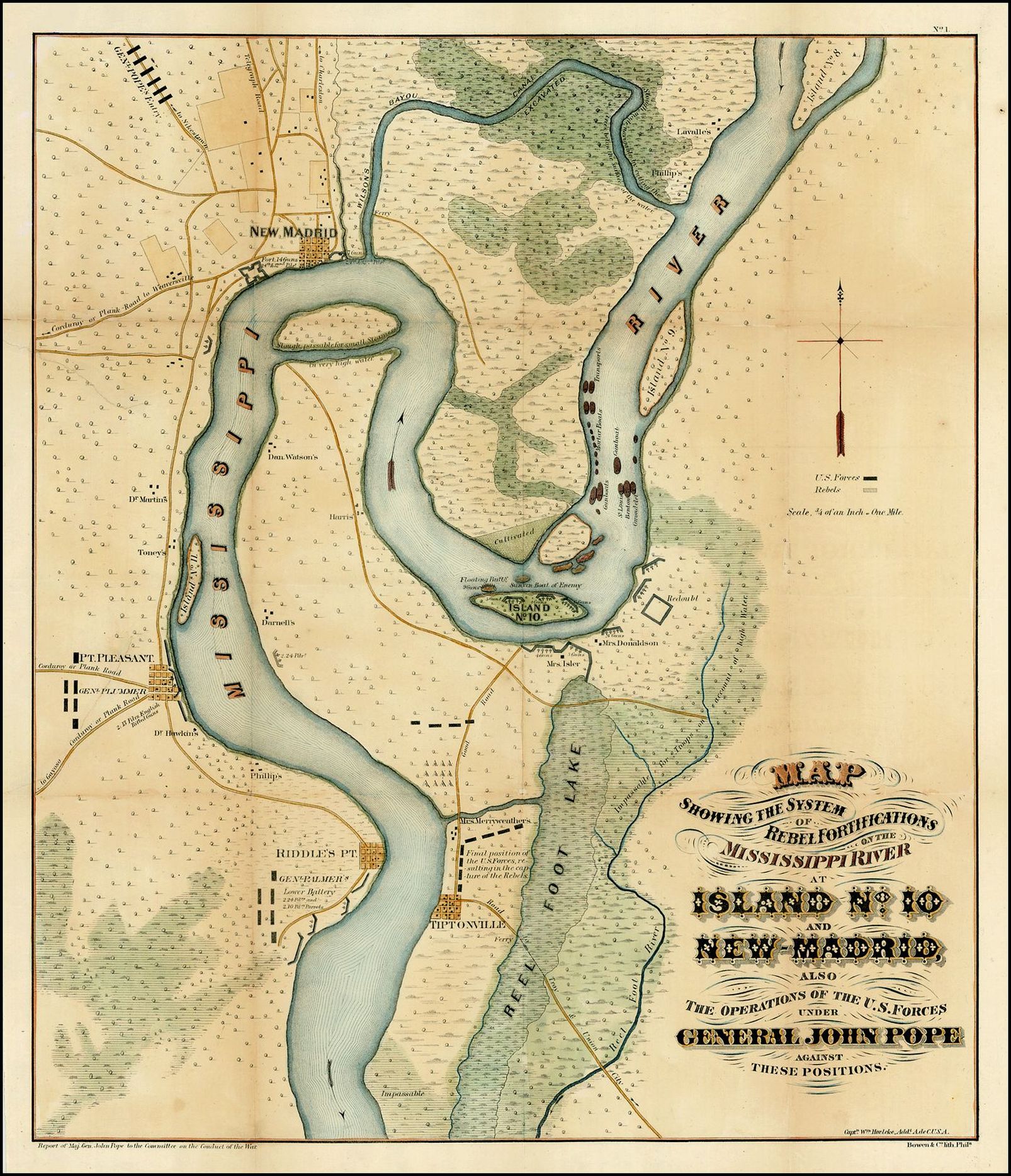

FORT PILLOW

and New Madrid. Office of the chief of engineers, US Army, 1862.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Nothing seemed to be able to stop the Federals juggernaut from moving down the Mississippi River. The forts at Island No. 10 had been captured, and Major General John Pope was able to occupy New Madrid, Missouri. The last major Confederate fortification defending Memphis was the 40-gun Fort Pillow, located 40 miles above Memphis. The US Navy had been shelling the fort since April 14, using 13-inch seacoast mortars. The mortar boats were towed into position by other ships, including ironclads, stationed to provide these mortar boats protection from any attack.[9]

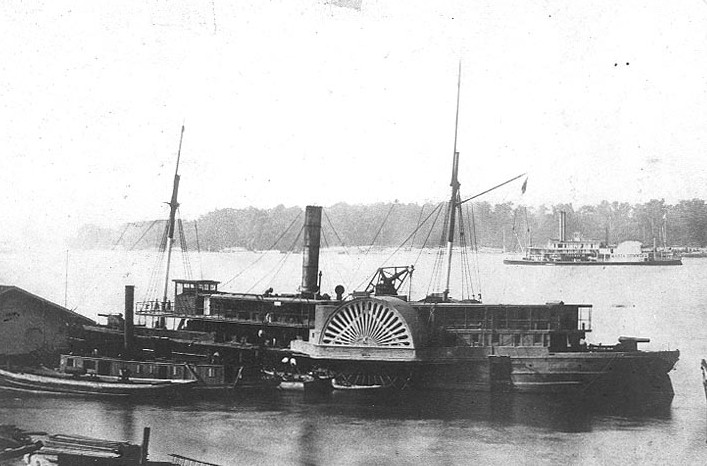

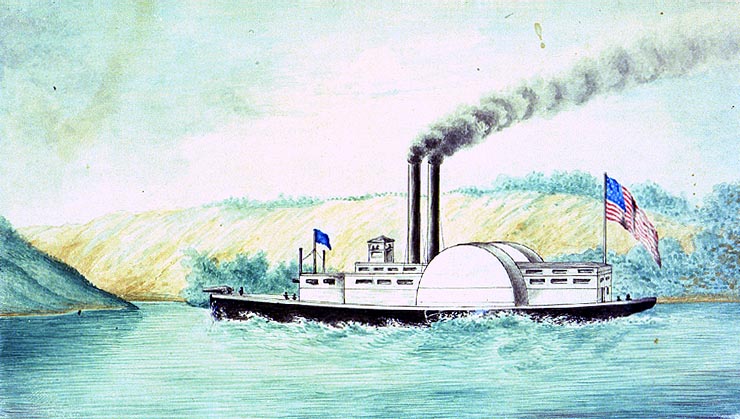

FEDERAL RAMS

Ellet had four of his rams in service with Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis’s Western Gunboat Flotilla. The ships included: USS Switzerland, USS Queen of the West, USS Monarch, and USS Lancaster. The ships generally carried little to no armaments as their reinforced bows were their mode of attack. The Queen of the West was typical of these ships. Built in Cincinnati in 1854 and converted into a ram in May 1862, the vessel was fast and used paddle wheels for motive power. The Queen of the West had three 12-pounder howitzers and one 30-pounder rifle. [10]

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:USS_Queen_of_the_West_(1854)_watercolor.jpg.

CONFEDERATE WARSHIPS

Eight vessels of the River Defense Fleet were sent north from New Orleans to defend the Confederate defenses above Memphis in late April 1862 to block the Union descent down the Mississippi River. These vessels included: CSS General Beaureguard, CSS General Bragg, CSS General Sterling Price, CSS General Earl Van Dorn, CSS General M. Jeff Thompson, CSS Colonel Lovell, CSS General Sumter, and CSS Little Rebel.

These ships were commercial riverboats, and no two were like other than being side wheelers; each generally had one cannon, often a 32-pounder. Nevertheless, CSS General Beaureguard was armed with four VIII-inch shell guns and one 42-pounder. The Little Rebel, the flagship of the Mississippi River Defense Fleet above Memphis, was armed with two 32-pounder rifles and one 32-pounder shell gun. [11]

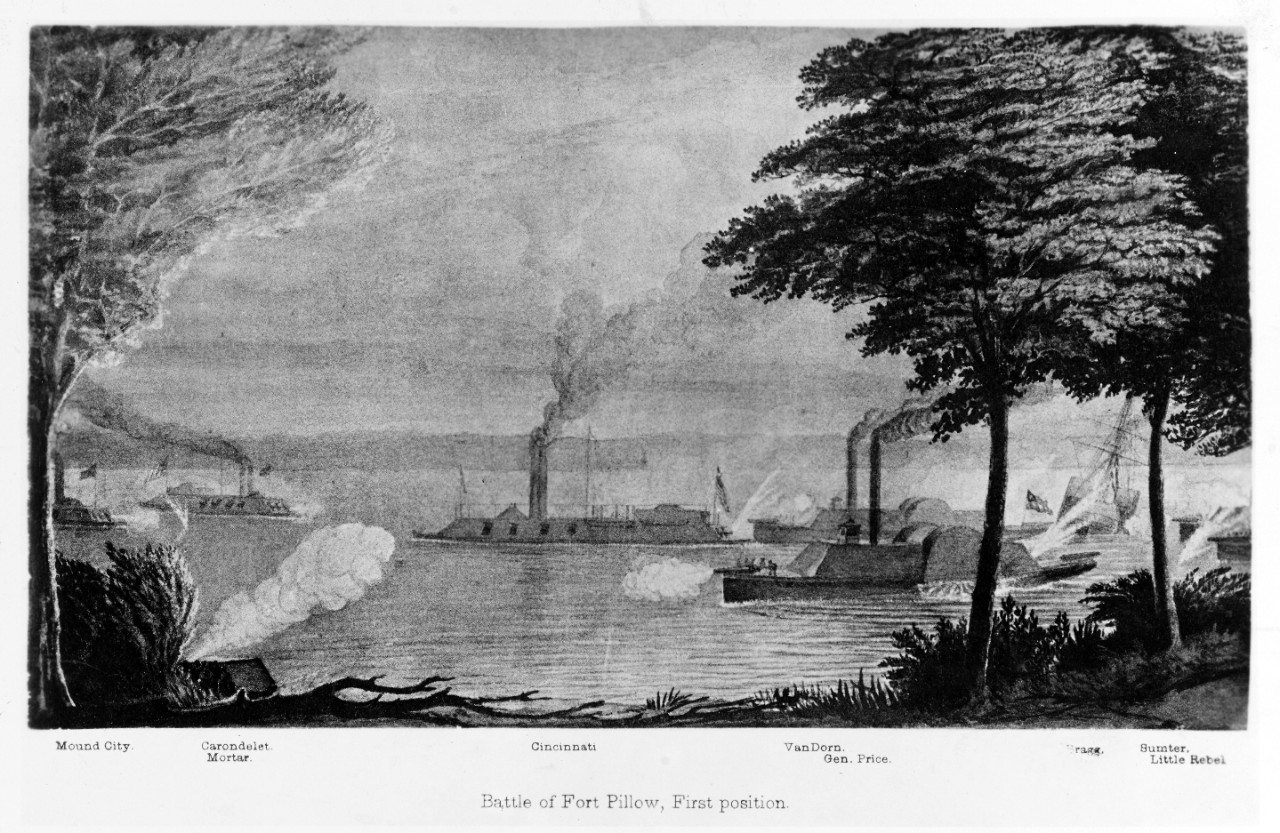

BATTLE OF PLUM POINT BEND

On the morning of May 10, 1862, one day after Flag Officer Davis had assumed command of the Western Gunboat Flotilla, the Confederates noted that USS Cincinnati was alone guarding a mortar boat with the rest of the flotilla a half-mile away at Bulletin Bar. The rams hoped to relieve the Union pressure on Fort Pillow, destroying one or more of the Union ironclads. The CSS General Bragg struck first, ramming Cincinnati on its starboard quarter just as the ironclad was getting underway. This strike turned both ships side by side. The Cincinnati took advantage of the point-blank range with its gun muzzles almost touching the Confederate ram’s side, firing a broadside, disabling it, and forcing it downstream.

Then General Sterling Price smashed into Cincinnati’s stern, disabling her rudder. Two other Union gunboats, USS Mound City and USS Carondelet, endeavored to stabilize the situation. The ironclads shelled General Bragg, cutting the ship’s tiller rope and forcing the ram to drift away from the fight. Then, General Sumter rammed the Cincinnati, inflicting severe damage, and that ironclad began to sink. The nearby mortar boat began to lob shells over Sumter to limit sharpshooters firing into the ironclad. The CSS General Earl Van Dorn fired two 32-pounder shells into the mortar boat, disabling it.

The General Earl Van Dorn steamed on and rammed Mound City just after Sumter had done the same. This severely damaged the ironclad so that it floated off and sank in shallow water. Then USS Benton and Carondelet arrived. The Benton shelled and damaged Colonel Lovell. As additional Union gunboats arrived, the damaged River Defense Fleet made its way downriver to Memphis.

Courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 55828.

The Confederates could have done much better; yet, without concert of action, they fought in a melee fashion, with each ram haphazardly selecting its target. The Battle of Plum Point may have been considered a minor Confederate victory; yet, the Federals were able to raise and repair Mound City and Cincinnati so that they would soon be back in action. Confederate rams that were damaged were quickly repaired. The Confederates suffered only two killed and one wounded, and the Federals had one wounded during this confusing hour-long battle. The major part of the action lasted only about 20 minutes.[12]

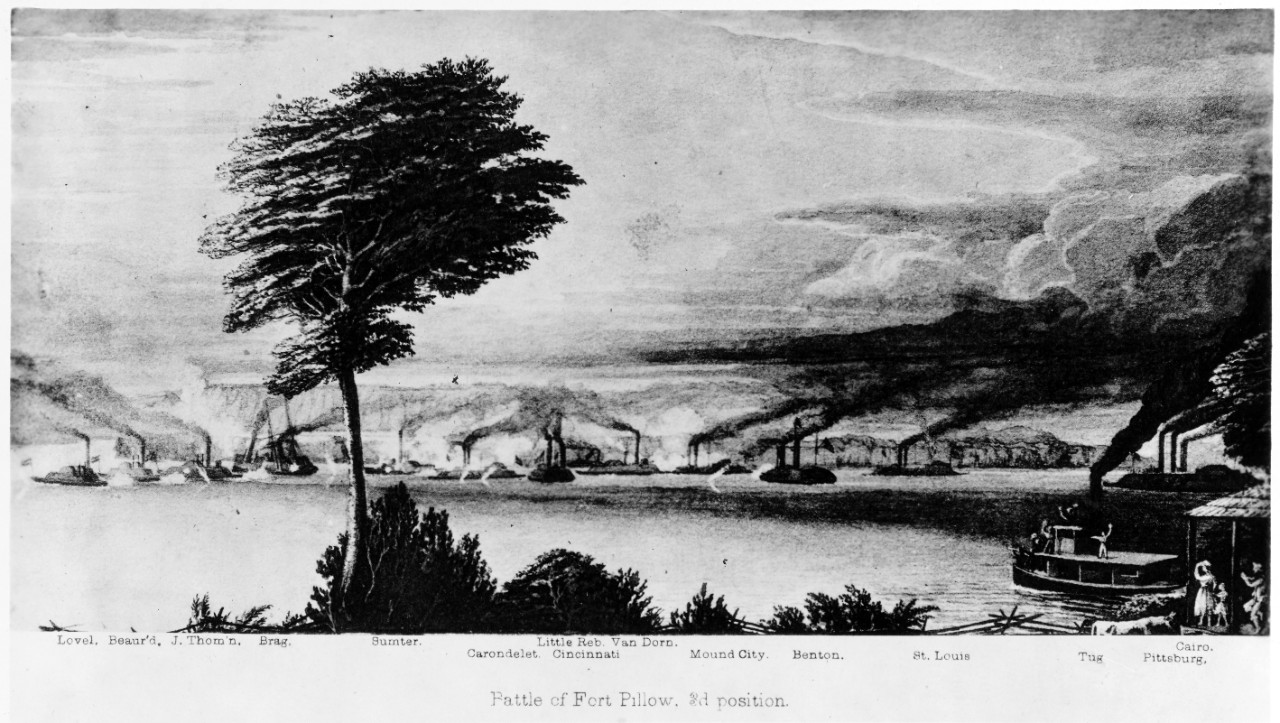

Naval Scenes and Reminiscences of the Civil War, Rear Admiral Henry Walke, 1877.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command NH 2049.

NO COAL TO BE HAD

Naval Scenes and Reminiscences of the Civil War, Rear Admiral Henry Walke, 1877. v

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command # NH42755.

.

When Corinth, Mississippi, was captured by the Federals, Memphis was abandoned by Confederate troops. The Confederate rams were ordered to move to Vicksburg; however, they could not find enough coal to make the trip. Accordingly, all of the captains agreed to stand and fight. [13]

THE BATTLE OF MEMPHIS

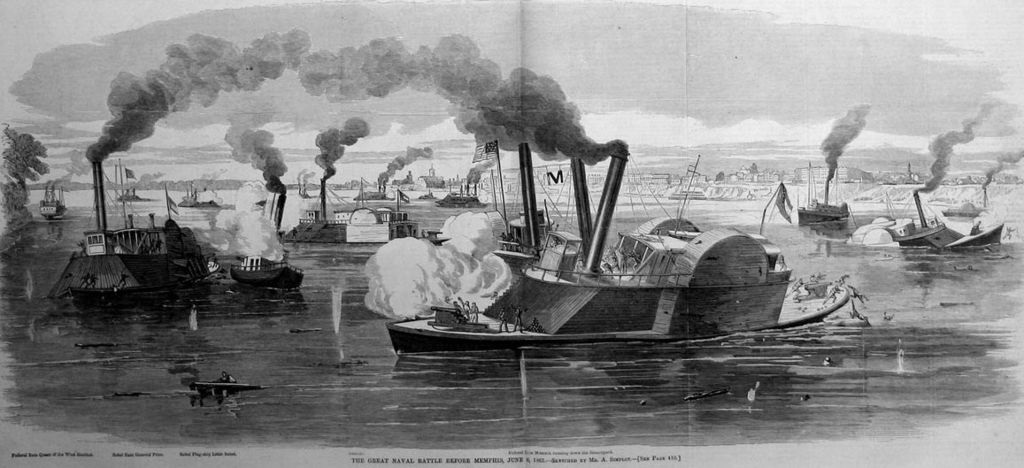

Alexander Simplot. Harper’s Weekly, June 28, 1862. Courtesy of Naval Historical Foundation.

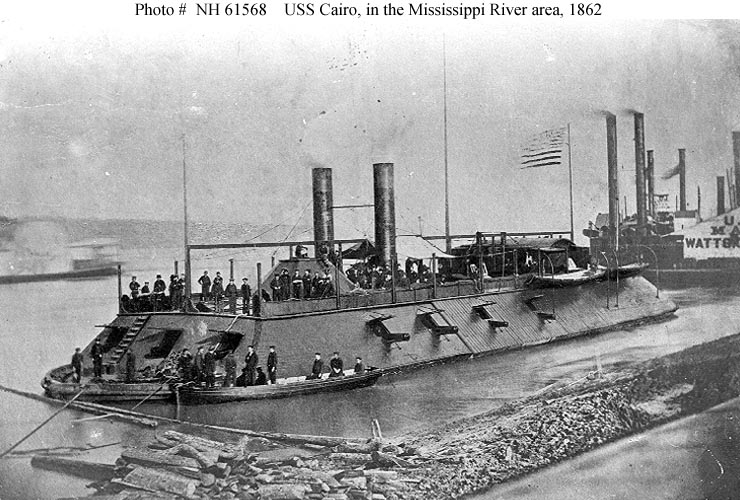

The citizens of Memphis lined the riverbank to watch the battle unfold. Davis had five ironclads: Benton, Louisville, Carondelet, Cairo, and St. Louis, in a line abreast across the river. They stood downriver with their sterns first. These Union gunboats traded shots from long-range with the Confederate ships.

Ellet then sped through and past the ironclads with two of his rams, Queen of the West and Monarch, headed toward the Confederate ships using their greater speed to rapidly engage. Ellet’s flagship, Queen of the West, struck first when it ran the CSS Colonel Lovell so hard that the Confederate ram nearly split in two. The Queen of the West was also severely damaged and sank in shallow water. Colonel Ellet was shot in the knee. The leg became infected, and he later contracted measles, resulting in his death on June 21, 1862.

The Monarch followed Queen of the West. Two Confederate rams, General Beauregard and General Sterling Price, attempted to ram Monarch simultaneously. Instead of striking the Union ram, the two Confederate ships rammed each other head-on; one of General Sterling Price’s side wheels was knocked away. The Confederate vessels somehow made it to the Arkansas shoreline, where they were destroyed by gunfire.

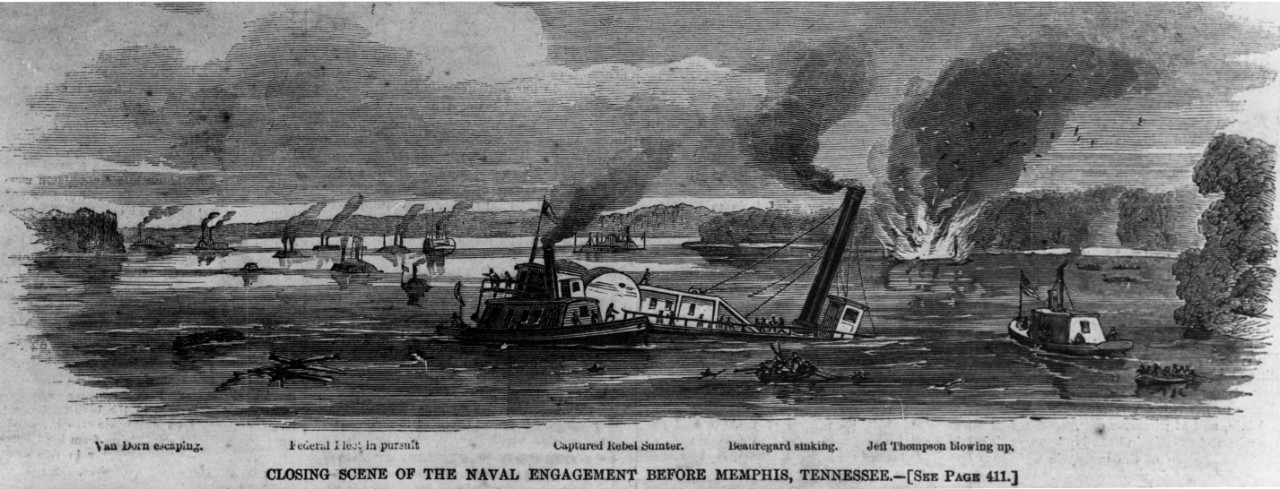

The Monarch then chased down General Beaureguard, and the ship was forced to surrender. Now the Union ironclads arrived on the scene and shot up General M. Jeff Thompson and forced Little Rebel ashore. The Carondelet sent a shot into General Sumter’s boiler, causing severe casualties. OnlyGeneral Earl Van Dorn escaped up the Yazoo River and was later scuttled. The Federals suffered one wounded, while the Confederates incurred about 100 killed and 150 captured during this two-hour engagement. The critical incidents of this battle lasted just over 30 minutes.[14]

RESULTS

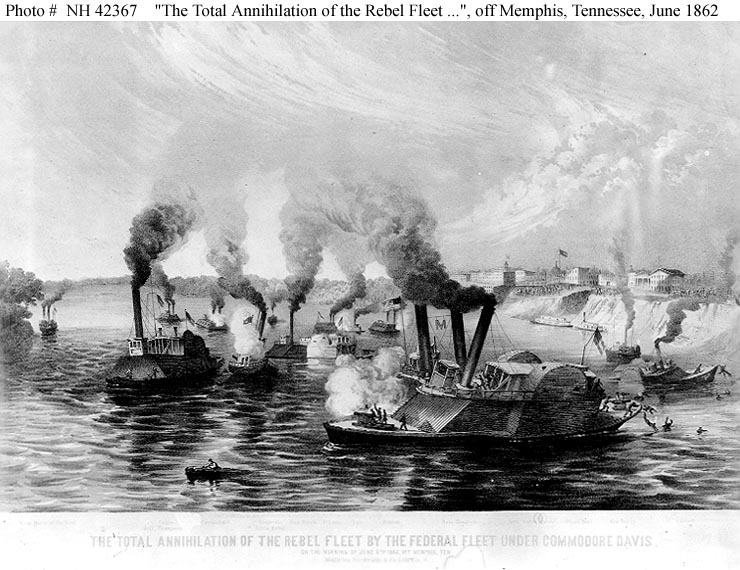

Lithograph by Middleton, Strobridge & Co.

Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command NH 42367

The battle of Memphis virtually put an end to Confederate naval resistance against Union advances up and down the Mississippi. Memphis was defenseless and was occupied that day by the US Navy. Unfortunately, the Federals failed to mobilize an effort to capture Vicksburg in June 1862 before it became such a fortress. The Federals raised and repaired three of the Confederate rams and added them to the Western Gunboat Flotilla.

The General Sumter was renamed General Pillow in a humorous reference to General Gideon Pillow, who fled from Fort Donelson in disgrace. “The only objection to the name,” Davis later noted, “is that the little thing is sound in her hull, which can’t be said of General Pillow. However, she resembles the general in another particular; she has a great capacity for blowing and making a noise altogether disproportionate to her dimensions.” [15]

Nevertheless, the defeat gave clarity to avoid a non-professional, disorganized command structure. Using poorly conceived and constructed warships, individual leadership lacked the ability to have concert in action, leading to the fleet’s destruction, highlighting the Confederates’ inability to stop the Union navy from gaining eventual control of the Mississippi River.

ENDNOTES

- Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies 1855-1883. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. 2001, pp. 168-169; and Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Armies In The War Of The Rebellion (Hereinafter known as ORA), Ser. 1, Vol. 10, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 38-39.

- John V. Quarstein, A History Of Ironclads, Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2007, pp. 124-125.

3.Patricia L. Faust, ed., Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Civil War, Harper & Row, Publishers, 1986, p 206.

- Quarstein, p. 138.

- Faust, pp.238-239; and Howard P. Nash Jr., A Naval History Of The Civil War. London: Thomas Yoseloff LTD, 1972, pp. 28-29.

- Nash, p. 29.

- Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Navies In The War Of Rebellion, (Hereinafter known as ORN), Ser. 1, Vol. 23, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1910. p.699.

- Bern Anderson. By Sea And By River: The Naval History Of The Civil War, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1962, pp.108-109; and J.E. Kaufman and H.W. Kaufman, Fortress America: The Forts That Defended America, 1600 To The Present. New York: Da Capo Press, 2004, p. 244.

- Silverstone, p. 121.

- IBID, pp. 168-169.

- J. Scharf, The History Of The Confederate Navy: From Its Organization To The Surrender Of Its Last Vessel, New York: Gramercy Books, 1996.

- ORA, Ser. 1, Vol. 52, pp. 37-40.

- ORN, Ser. 1, Vol. 23, pp.162-163.

- IBID, p. 210.