At the beginning of this year, I came across an article in the Virginian Pilot that discussed a coin collection held at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras, NC. All of the coins, 55 in total, were found on the beaches of the Outer Banks by a couple who visited the barrier islands starting around 1940. Impressively, some of the coins are over 2,000 years old and come from Ancient Greece and Rome. My mind raced – I immediately wondered if our own museum held similar coins.

To say I was surprised would be an understatement. We have more than a few coins from the ancient world, some of which are in excellent condition like the silver piece above. On this coin that is well over 2300 years old, we see a floating galley on the reverse and a curious figure on the obverse. Some records of similar coins from the Phoenician city of Arados label their male figure as Poseidon, or sometimes Zeus, but these are Greek deities.

Rather, I think this bearded figure wearing a laureate is Melqart. This deity, whose name translates to “King of the City,” was the patron god and head of the pantheon of Tyre, a Phoenician city-state which was located across the water from Arados. He was also referred to as Ba’al de Sor, Lord of Tyre, and was associated with the monarchy, commercial trade, the sea and colonization. Interestingly, Melqart was well-known in Semitic religions, and could likely be the Ba’al mentioned in the Tanakh. Additionally, he is linked to the Greek Herakles and Roman Hercules, often being called the Tyrian Hercules. But despite the shiny draw of this particular silver piece, this was not the coin or collection that caught my eye; instead I was taken by a more unassuming numismatic (the study or collection of coin and paper currency) collection.

Commodore rodgers & his demure wood box

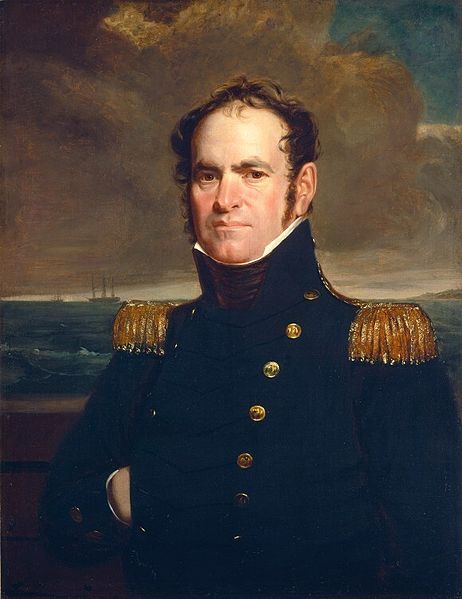

While I searched through our online catalog for Greek coins, one image that popped up in the search was the box pictured below. “How curious,” I thought, “for a box to be revealed in a search for coins?” I quickly clicked on this object and discovered that this box, whose lid is decorated with simple Regency-style inlay and a metal inset-medallion engraved with “J. Rodgers”, housed the coin collection of Commodore John Rodgers.

The Rodgers family, as a whole, was key in the foundational efforts of the American Navy. Commodore Rodgers’ father, Colonel John Rodgers, was a Scotch emigre to the American colonies prior to the American Revolution, and was a proponent of the patriot cause. Commodore Rodgers followed in his father’s footsteps and served for nearly 40 years and under 6 presidents in the Navy’s nascency. He was a prominent war hero who served in the Quasi War, the First and Second Barbary Wars, and in the War of 1812. From 1815-1837 he served on the Board of Naval Commissioners, and died one year after his retirement. His son, John Rodgers Jr, and four of his grandsons, all served in the United States Navy.

But let’s get back to the box and the coins held within. There are 16 coins in total, and all appear to originate from antiquity (roughly two-thirds of these coins are from Greece or neighboring semitic city-states). It is my belief that Rodgers collected the Greek and Roman treasures while he was commanding the Mediterranean Squadron from November 1824 – May 1827. All of the coins show a decent amount of wear, or what I like to think of as love from Commodore Rodgers. So I spent some time looking through various coin records and collections to find matching coins with similar details to a few of Commodore Rodgers’ coins.

A little Numismatic History

So far as we have any knowledge, they [the Lydians] were the first people to introduce the use of gold and silver coins, and the first who sold goods by retail. – Herodotus

Something about history that I love – it is always changing as archaeologists continue to uncover more of world history through discovered artifacts. So, we typically say “the oldest known…” because there is always the chance that we could find something older. In fact, it was only 2 weeks ago that scientists discovered the oldest known cave painting, a pig painted 45,500 years ago in Sulawesi, Indonesia (before this, the earliest known cave paintings were also from Sulawesi cave complex and dated to 44,000 years ago)! Thus, the oldest known minted coins were produced in Lydia, present-day Turkey, around 625 BCE. These were made of electrum, a silver and gold alloy, and usually had an image of a lion on the obverse and two incuse squares on the reverse. Incuse marks are the marks made by the hammer used during the minting process; when there is an image on the reverse, these marks are not present.

This was not, however, the first time that a precious metal was used for currency. Prior to the Lydian government minting coins, rings or ingots (bars) of metal could be used in trade; but in order to discern their value, these bits of precious metal would need to be weighed. With a government entity in charge of minting, coin standards and weights were put into place, thereby eliminating this time-consuming task. Around the year 550 BCE, King Croesus replaces electrum with pure silver (or occasionally gold) coins.

The preferred coin standard was the Athenian drachma, which weighed 4.3 grams of silver, and all other coin weights are based off of this. The Corinthian stater, for example, weighed 8.6 grams of silver. Interestingly, the word drachm(a) translates to “a handful” or literally “a grasp.” The drachma is made up of 6 obols, Greek for spit – like a rotisserie spit – and 6 spits makes a handful, which suggests that prehistoric Greeks used spits as a means of transactional currency. All of this means that the nomenclature of drachma, a currency used in Greece until 2002 when it was replaced by the Euro, directly relates to pre-numismatic time!

The Rodgers’ Coins

Now that we have the history out of the way, I’d like to share a few of the coins in the Rodgers’ collection of which I am particularly fond. Greek numismatic periods follow the same periods of Greek art: Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman (called Roman Provincial coin); and I’ll present our coins in this order, alongside images of similar coins from other collections.

There are a few things to know about Greek coins that help us verify authenticity, and also determine their locale. All Greek coins are handmade, and therefore they are all imperfect! If a coin appears to be machined, we can instantly tell that it is counterfeit. Additionally, Greece was composed of more than 2000 independently regulated city-states and roughly half of these each produced their own coin. Typically, each city-state would mint their coin with their specific patron deity on the obverse and a symbol or important emblem of their city-state on the reverse.

Archaic period: 7th C BCE – 480 BCE

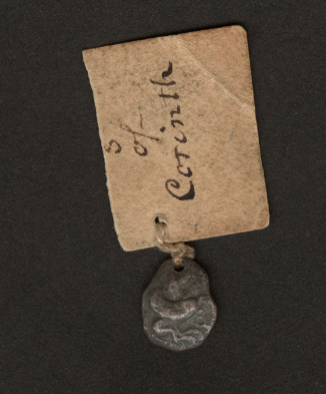

This coin is the Pegasos Stater of Corinth, a Corinthian coin from the time period of King Croesus, and it is one of the oldest items in the Mariners’ Museum collection. On the obverse is the winged horse of the pegasus with a symbol below the horse called a qoppa, which was the lettered symbol associated with Corinth’s name. On the reverse of the coin are 4 incuse marks that are referred to as quadrapartite marks consisting of a swastika. In this case, it is a left-facing swastika that is composed of four gammas (Γ) called a gammadion, and is an auspicious symbol. Below is an image of a similar coin with less aging.

Classical Period: 480 – 330 BCE

The above triobol coin dates to 478-460 BCE and comes from Phokis (or Phocis), an ancient federation of 20 townships that included the city of Delphi. It was located in central Greece and served as a crossroads for much of Greek history and religion, being divided by Mount Parnassus and including the pass of Thermopylae, the city of Doria, and the Oracle of Delphi. This coin features a bull on the obverse and profile image of the god Artemis on the reverse. Curiously, all records I have found name Artemis on the reverse, rather than the obverse.

It is possible that the bull on the obverse is a representation of the bull sacrifice that would be made during Pythian community festivals. However, I think the bull might be a representation of the bronze bull statue that the Corcyraeans dedicated in 480 BCE to commemorate an especially hefty catch of tuna. According to Greek geographer Pausanias, herders in Corfu noticed a bull fleeing his flock each day and heading to the water; they followed and found a sea full of fish – yet they were unable to catch any. After seeking advice from the Oracle at Delphi, they sacrificed a bull to Poseidon and were finally able to catch the fish. They then used proceeds from the fish to erect the bronze bull, a clear image of which (I believe) is on the coin below.

Hellenistic Period: 330 – 31 BCE

Typically, the symbol of a city-state is something they are known for, an export they have, or a symbol of their patron deity. For example, the symbol of Athens was the owl, which was their patron deity, Athena’s, symbol. Knossos would typically depict a labyrinth or a minotaur, Corinth would display the pegasus, and Esphesus would have the bee, the symbol of Artemis. But Rhodes was different; instead of a symbol of their city-state, they chose a play on words with a depiction of the rose, whose Greek word was Rhodon.

On the reverse of this coin, like the one below, we can see a small rose inside an incuse square. This series of coins, called the plinthophoric series, ran from ca. 190-84 BCE and derives its name from plinthos, meaning brick. The rose design was carved on a small plinth, rather than taking up the entire reverse of the coin like others we have seen in this collection. On the obverse of the coin is a profile image of Rhodes’ patron deity Helios wearing a radiate crown.

Roman Provincial Coin: 31 BCE – Dissolution of Greek city-states

The Hellenistic Period ends with the Roman conquest at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC and the subsequent fall of the Ptolemaic Empire in the year following. With this, coinage in Ancient Greece changes as Roman coinage is preferred and seen as more valuable. However, Imperial Rome still allows Greek city-states to produce their own coin for local trade and as a matter of expediency.

This coin from our collection is very worn and difficult to discern the images, but not impossible. Our catalog states that the obverse could feature Athena or Minerva, the Roman equivalent to Athena; and the reverse features some lumps that could be an owl. It is my hope and belief that this is correct, and it would fall in line with numismatics of the period. Below I have found what I think is a similar coin with Minerva on the obverse and an owl on the reverse. Additionally, both of these coins were made of bronze, something that was becoming more common during the Roman provincial period as silver was being phased out of coinage.

Playing favorites & Parting Thoughts

Normally it would be difficult for me to choose a favorite among such a wonderful collection, but in this case, it was easy because, quite frankly, I adore a little controversy. We have a coin from the Classical Period that features Herakles fighting the Nemean lion on the reverse, and on the obverse is an image of a deity, who our catalog names as Athena wearing a Corinthian helmet.

However, I wonder if this is correct, and I am going to pose some theories. For one, this helmet does not have the bulge above the crown of the head that is typical of the Corinthian helmet Athena wears. As for our mystery subject, the tag which accompanies the coin simply says “Miltiades,” likely referencing the Athenian general who, in 490 BCE, defeated the Persians at the Battle of Marathon. Could this be our obverse hero? Finally, my personal favorite theory is that the figure on the obverse is Herakles’ father, Zeus, like in the coin below. But without a little more research, we won’t know for sure!

And yet, this coin is not my favorite item in the Commodore Rodgers collection – that place is held by a very special miniature painting of the Commodore featuring a lock of his hair. But I think I will have to save hair miniatures for a different blog (our Victorian friends who made these would actually wear them!). So as I sign off, I implore you to do your own investigation into Greek numismatics – search our online catalog for all the coins we have, or look into other collections around the world. It might even lead you to something you’d never expect to find.