In November we had quite an influx of researchers to the Museum. I frequently heard some of my colleagues quietly grouching about having to drop what they were doing to assist them but you know what I say? BRING IT ON!

Let’s admit it, despite being one of the larger maritime museums in the United States there’s no freaking way we could employ a subject-matter expert in every single area our collection covers. With this reality in mind, about fifteen or twenty years ago the Museum began shifting from the museum-world norm of having specialist curators who oversee a particular aspect of the collection towards a smaller staff of generalists who are able to research and discuss a broad range of topics. Despite my very long title of Director of Collections Management and Curator of Scientific Instruments if you had to guess my specialty by looking at my blog posts you’d be hard pressed to settle on just one thing.

Having outside experts use our collection to research their own projects is a great thing because even though it’s sometimes inconvenient and frequently time consuming it ALWAYS yields some new information about an object or image in our collection. This was especially the case in November when two researchers, Kevin Foster and Emir Yener, showed up to research Civil War era blockade runners and nineteenth century warships. During their visit, not one but two objects went from being completely unidentified to having full catalog records. We were also able to update many other records with search terms that would make them easier to find.

The first breakthrough occurred as Kevin and I were plowing through the collections looking for images of blockade runners. Because of the role it played in the South’s blockade running effort Kevin was also interested in seeing images of Bermuda. During our conversations on the first day of his visit Kevin asked me if we had any artworks by Edward James. James had been hired by the US Consul to Bermuda, Charles M. Allen, to make sketches of blockade runners to help aid the Union fleet’s identification of the vessels (they changed their names often so you couldn’t rely on name alone). Interestingly, James also sold copies of his sketches to the crews of the runners themselves thereby increasing his profits and “proving” his status as a neutral party in the conflict (at least in his own mind!). Unfortunately, a quick search of our computer system yielded no results for the artist’s name but we did have several images of Bermuda.

Kevin and I continued to plug away on our search and each night he would go back to his hotel, get on the computer and search for additional possibilities. On the third morning of his visit Kevin arrived at the Museum excited because he thought he might have found an image by James in the collection. We jumped into the computer, pulled the object’s location and headed into storage. And do you know what we discovered? Kevin was right! And it’s no wonder we didn’t know we had an artwork by Edward James in the collection–the full extent of the cataloging included exactly three pieces of information: 1) it was a watercolor, 2) it showed St. George’s Bermuda (the image was originally identified as Hamilton but in 2017 I was able to confirm it was St. George’s using Gleason’s Pictorial) and 3) it had an artist’s monogram, which had been interpreted as “JE” not the other way around.

Kevin knew a lot about James’s work and was able to provide quite a bit of detail regarding the scene including the relative time period when the event occurred. I immediately went to work reading everything I could on blockade running and Bermuda (which is why it’s taken so long to get this post out!) to fill in some of the details and background story. All of this work has taken us from sad three pieces of information to a fully researched and cataloged object.

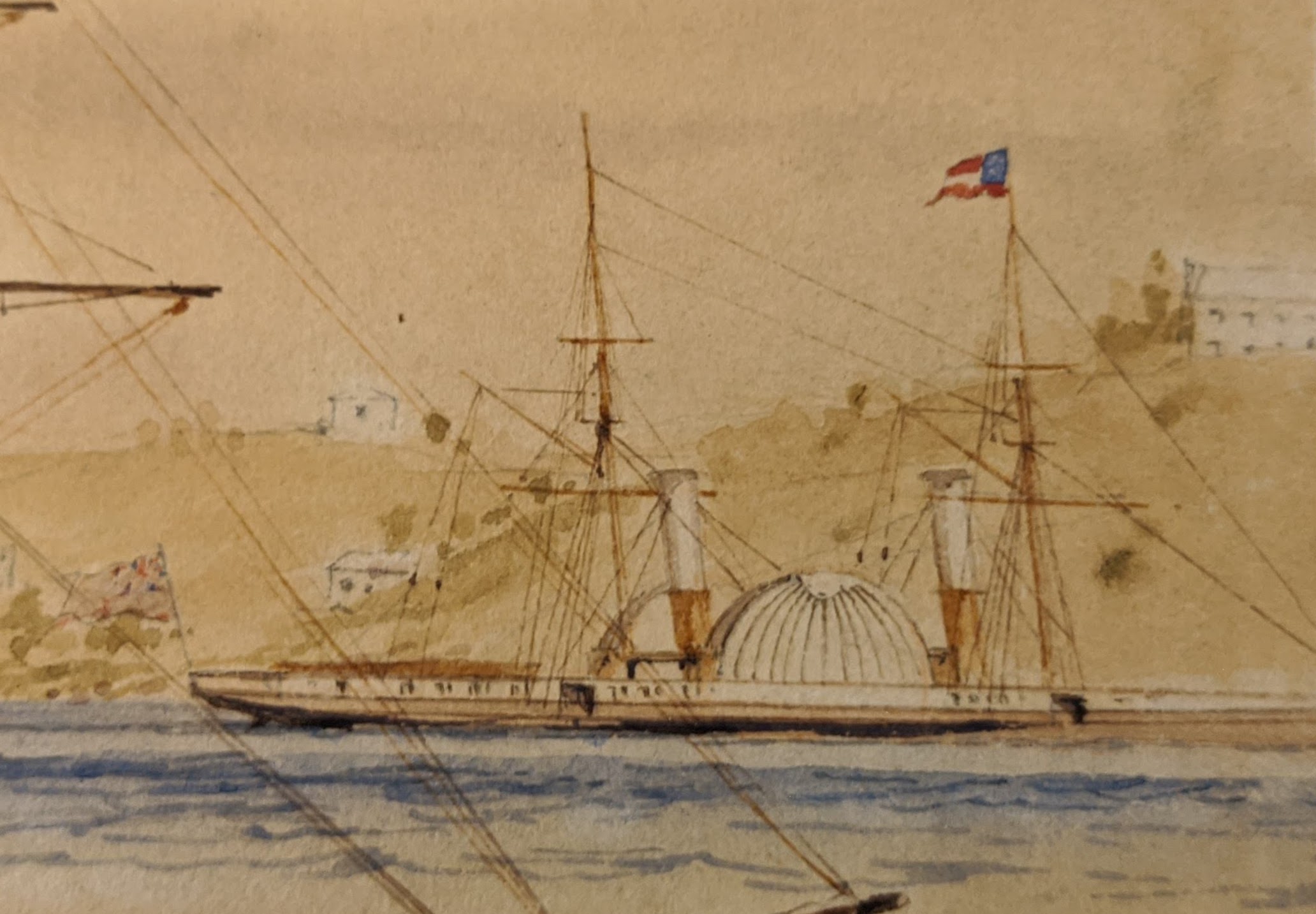

James’s image shows British and American ships and blockade runners in the harbor of St. George’s, Bermuda. The American warship at the center has a cloud of smoke behind her which can only mean two things: 1) she’s blasting the holy hell out of an undefended, neutral port owned by another country, or 2) she’s firing a salute. I think I’ll go with number two. This particular event occurred on September 27th, 1862 when three ships under the command of Acting Rear Admiral Charles Wilkes arrived in Bermuda. The ships were the USS Wachusett, USS Sonoma and USS Tioga.

The ships were part of a seven vessel “flying squadron” organized by the Secretary of the Navy “with a view of sweeping from our coast and the neighboring waters the lawless contrabandists who made it a business to violate our blockade and promote the efforts of those who are engaged in schemes to break up our Union and subvert the Government.” Despite this sweeping statement the prime reason for visiting Bermuda was their search for the elusive “290” (CSS Alabama)–it wasn’t there but that didn’t stop Charles Wilkes from making a total nuisance of himself and nearly causing an international diplomatic incident.

Wachusett and Tioga entered St. George’s harbor and Wilkes left Sonoma cruising outside to intercept any ships that attempted to leave port. Upon entering the port Wilkes was perturbed to find no national flag displayed at the flagstaff on shore and when Wachusett fired the traditional formal salute it was not returned until Wilkes sent an officer ashore. Sonoma’s activities outside the port, essentially a form of blockade, quickly irritated Bermuda’s governor, Colonel Harry St. George Ord, and after two days he sent a naval lieutenant to tell Sonoma’s commander, Thomas H. Stevens Jr., he must either anchor inside the harbor or stand off to sea. Stevens refused which led to some sharp correspondence between Wilkes and Ord. After Ord apologized for the delay in recognizing Wachusett’s salute Wilkes ordered the Sonoma into port (October 1st). This further reinforces the dating of the scene as only two US ships appear in the image.

To the left of Wachusett are the steamers Minho (flying what looks like a Swedish flag) and tiny 73-ton Ouachita (flying an unidentified house flag). Minho is easily identified by her weird looking masts. She left Charleston on August 27th with 600 bales of cotton and ten passengers and despite the short trip (she arrived September 1st) managed to run out of coal. The result is clearly described in a September 10th letter from Consul Charles Allen to the US Secretary of State William Seward “The Minho…a screw steamer of about 300 tons painted light lead color. Her mainmast entirely gone. Fore and mizzen top masts with all spars gone.” Clearly the crew resorted to burning all those wooden bits in an effort to generate enough steam to keep her engines running.

Directly behind Minho’s smokestack is Ordnance Island. The vessels next to it are probably taking on or discharging cargo. To Minho’s left USS Tioga is anchored against the wharf, most likely in the process of taking on coal. The American flag flying behind her is the American consulate building (where Edward James lived and worked). Heading back to the center of the artwork the little British flagged vessel sitting at the bow of Wachusett is the Bermuda government’s steam screw yacht Siren. Between them, in the extreme background, is a ship on the horizon. Could this be USS Sonoma on “blockade” duty or HMS Desperate (desperately) trying to keep Sonoma away from the port?

The two large vessels to the right of Siren are the blockade runners Gladiator and Harriet Pinckney. Harriet Pinckney was owned by the Confederate government and had been anchored in St. George’s harbor since August 27th with a shipload of “arms and a field battery” but no sailing orders from Richmond. The 700-ton screw steamship Gladiator had arrived at St. George’s on August 23rd and was loaded with 20,240 guns and Enfield rifles, a large quantity of powder, cartridges, caps, shells, cartridge paper, blankets, army cloths, and other items. She’s recognizable by her long black hull sitting low in the water at the stern and her upright stem (that’s the pointy, curvy piece at the front of the ship) that has no billet or figurehead. Gladiator was one of the few blockade running vessels that survived the war without getting caught.

At the extreme right in the background sits the forlorn Merrimac–the only ship blatantly flaunting her allegiance by flying a Confederate first national flag on her foremast. She was sitting at St. George’s awaiting orders when her owners, Z. C. Pearson and Company, declared bankruptcy. On October 21st, Consul Allen reports that Merrimac and another vessel (Phoebe) were seized and held on “orders from England.” Interestingly, Merrimac had arrived at St. George’s on September 5th while on a voyage from London to Nassau. Among her cargo were three 8-inch Blakely rifled cannon and 1,100 barrels of gunpowder. When Merrimac was seized by Pearson’s creditors Southern agents were unable to remove their cargo from the impounded steamer. They solved the problem by buying the ship and cargo for £7,000 and placing her under the control of the Confederacy’s Ordnance Bureau. The ship delivered the guns to Wilmington in April 1863 and was promptly sold.

On October 1st the Tioga headed out of port and the Wachusett and Sonoma followed soon after. Not content to leave all those blockade runners just quietly sitting in port Wilkes stationed Tioga and Sonoma off the port to try and prevent any vessels from escaping. When Gladiator left port she was stopped and boarded but her paperwork was found to be in order and she was allowed to proceed (most likely saved by the presence of a nearby British warship and the fact that the US Navy officers could see other vessels trying to slip from the port and were anxious to stop them!). On October 10th Ouachita managed to slip out of port but was captured by the USS Memphis on the 14th. Minho managed to slip past the two blockaders on the night of October 12th but was fired upon by the USS Flambeau as she tried to enter the port of Charleston on October 20th and sunk. Quickly running out of fuel, the Tioga and Sonoma left Bermuda a short time later.

As I mentioned at the beginning of my post we had a second artwork identified during the same week. Meeting Kevin at the Museum was researcher and Phd candidate Emir Yener from Istanbul University. Emir took a break from his research to look at some of the Turkish items in our collection. One of the images we showed him was a watercolor by artist William John Huggins of an unidentified Turkish vessel. He was immediately able to identify the vessel as Peyk-i Şevket, a Turkish steam paddle ship.

Peyk-i Şevket was built and launched in 1836 by French businessman Louis Benet in La Ciotat as the 330-ton paddle steamer Le Phocéen and was reputedly the first steamship in the Mediterranean. As Le Phocéen the ship made pleasure cruises around the Mediterranean; visiting Marseilles, Algiers, Tunis, Malta, Navarino, Smyrna, Istanbul, Athens, Malta, and Palermo before steaming back up the coast of Italy. In February 1838 the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Mahmoud II purchased the ship and renamed her Peyk-i Şevket, which means ‘Messenger of His Majesty’ or ‘Messenger of Magnificence’. The ship was used to transport goods and passengers between the ports of Istanbul and Izmir.

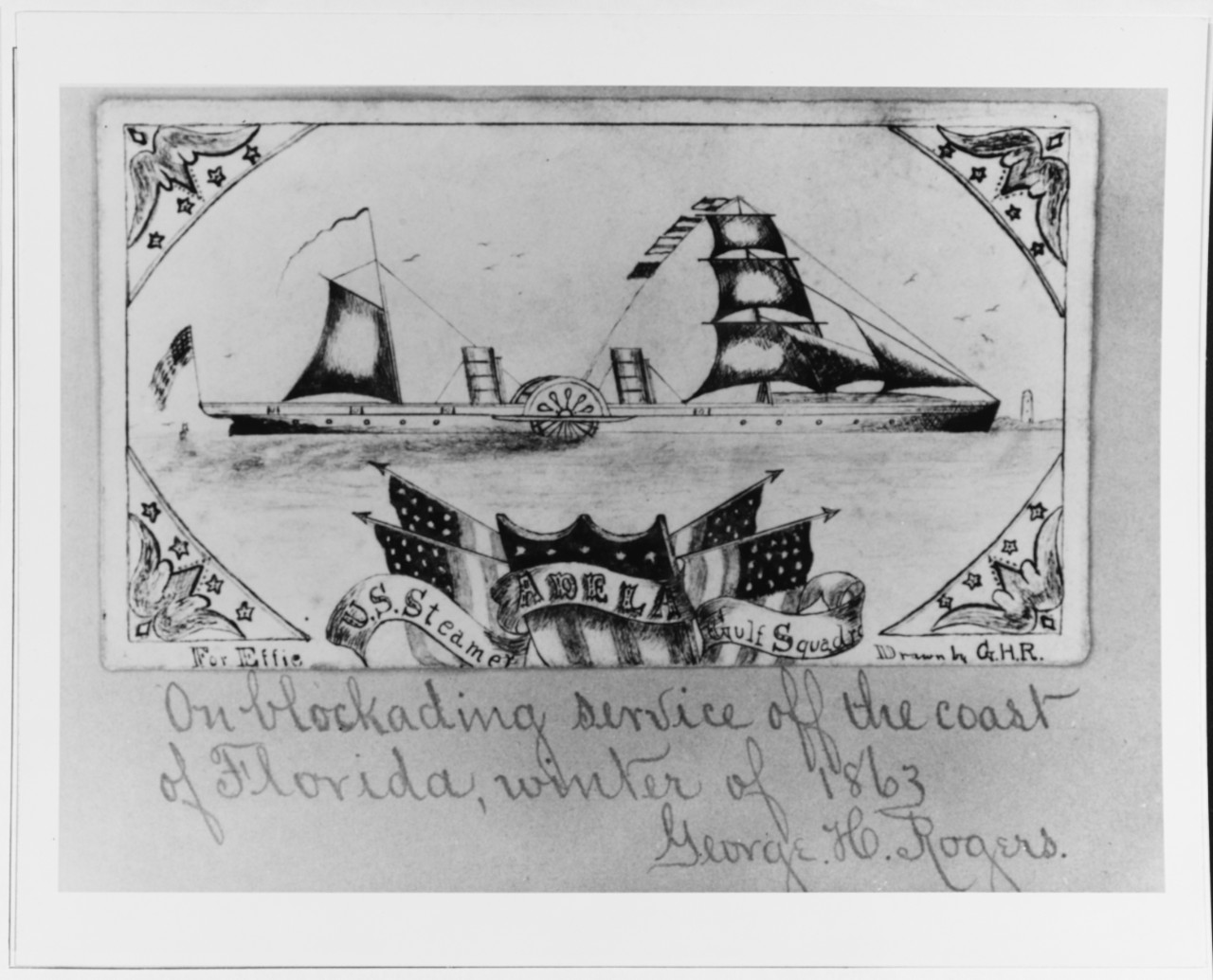

The benefits of having Kevin and Emir visit keep rolling in. Just this weekend Kevin helped me identify the ship on a piece of china. While researching the list of vessels painted by Edward James I discovered a china plate with an image of a vessel that looked suspiciously like a blockade runner. It was identified as the 205-ton Adela built by Caird & Company in 1877. I showed Kevin an image of the plate and he sent an image that showed the Adela of 1877 which only had a single smokestack–the ship on our plate had two. He later sent a photograph of a drawing made by Pharmacist’s Mate George H. Rogers of the USS Adela, a ship that looks remarkably similar to the vessel on our plate.