One of my Facebook friends recently fussed with me about posting an image of Christopher Columbus on October 8th with the statement that it was probably the one time that a man refusing to ask for directions was a good thing. His comment? “Not for the natives.” So I thought I would relate this bit of history I learned while working on the Gallery Crawl as it was one of the times where the native population put the Europeans in their place.

16th century portrait of Ferdinand Magellan (Accession# QO 796)

16th century portrait of Ferdinand Magellan (Accession# QO 796)

The story starts in 1519 when Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan set out from Spain with a fleet of five ships to search for a western sea route to the Spice Islands. En route, he discovered a strait at the bottom of South America that provided a difficult to navigate, but safer route to the Pacific than going around Cape Horn.

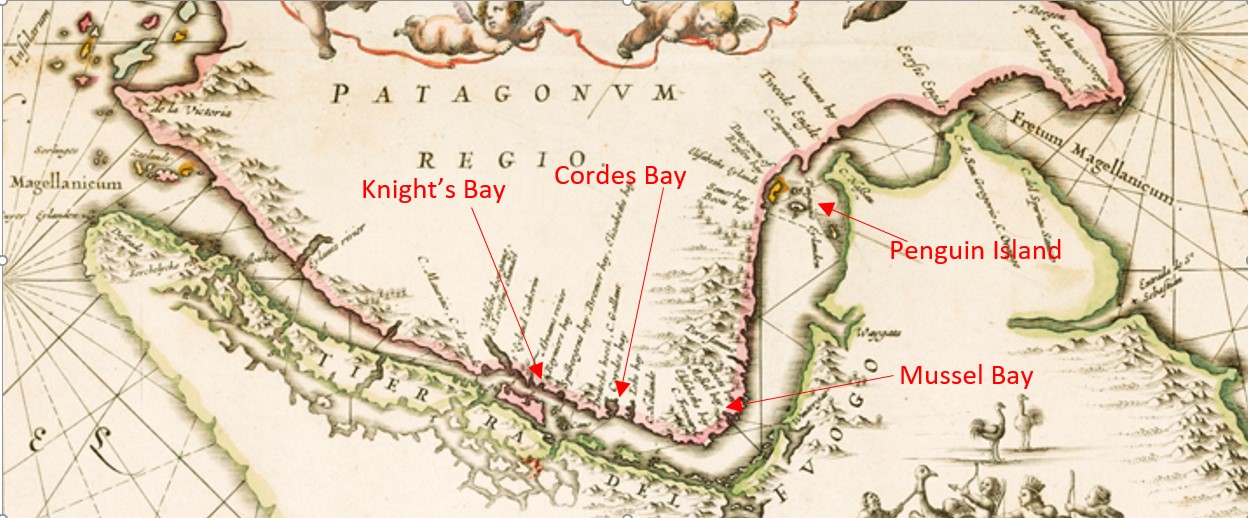

Map published in Amsterdam by Joannes Janssonius sometime after 1646. The map depicts a very simplified passage through the Strait of Magellan and shows the “Patagonum Regio” (the “Kingdom of Patagonia”). The image shows penguins and native population hunting rheas (large flightless birds distantly related to ostrich and emu).

After sailing through the strait, Magellan’s ships crossed the Pacific and reached their intended destination—without Magellan—he’d been killed in the Philippines. About three years later one ship made it back to Spain with only 18 of the fleet’s original crew of 270 remaining. The ship, however, was laden with 381 bags of cloves which were worth more than the total value of the five ships that started the voyage!

Anxious to get in on the spice-trading action, two Dutch merchants, Pieter van der Hagen and Johan van der Veeken, formed the Magelhaensche Compagnie and hired the merchant/explorer Jacques Mahu to find a trade route to the East Indies. The expedition left Goeree (Rotterdam) on June 27, 1598 with five ships: Hoop (Hope), captained by Mahu; Liefde (Love), captained by Simon de Cordes; Geloof (Believe), captained by Gerrit van Beuningen; Trouwe (Faith), captained by Jurriaan van Boekhout; and finally Blijde Boodschap (Good Tidings), captained by Sebald de Weert. Despite the inspirational ship names, things began going wrong for the expedition before they even made it across the Atlantic Ocean.

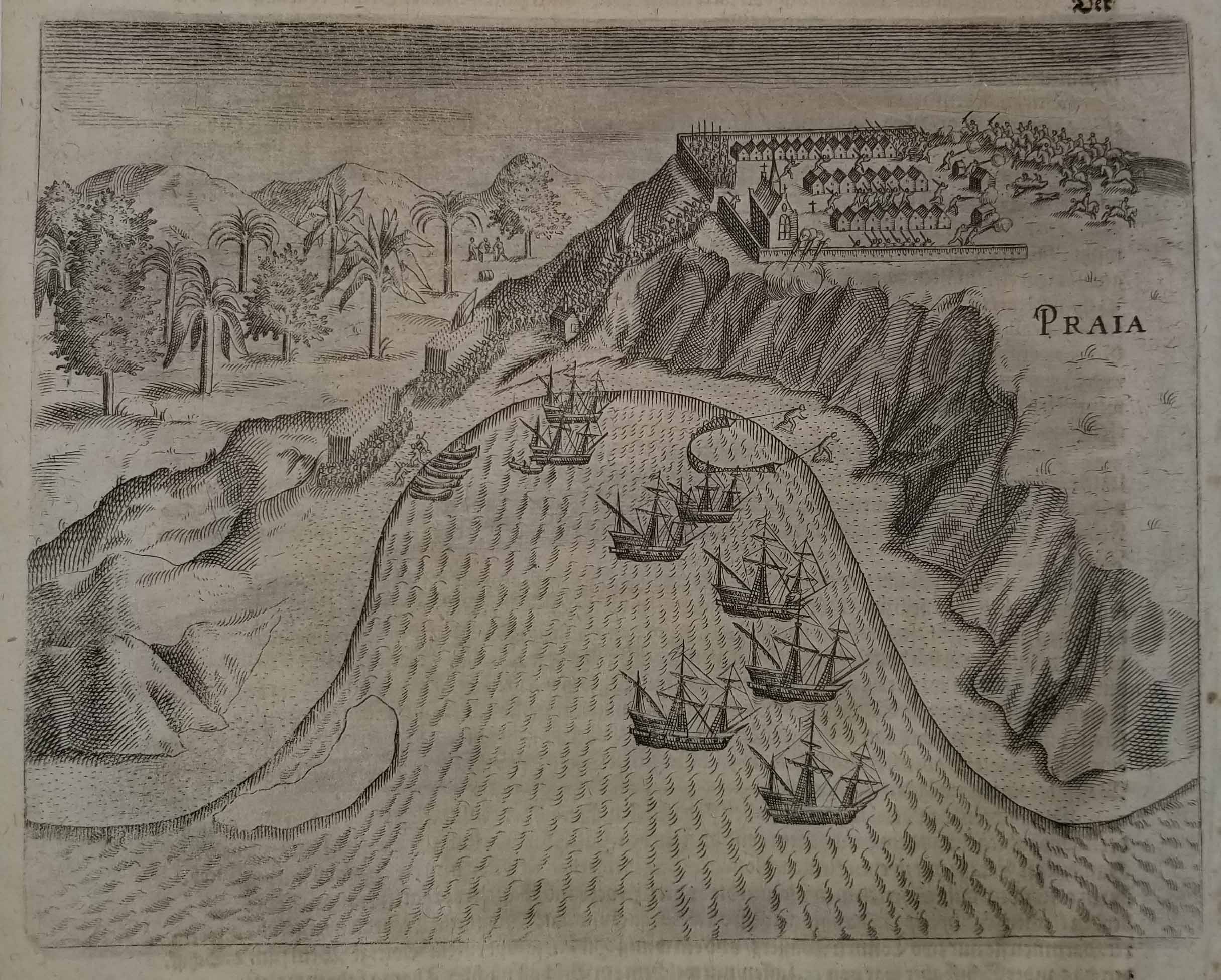

The expedition’s first stop was at Praia in the Cape Verde Islands to pick up fresh supplies. It should come as no surprise that the Portuguese governor of the island refused to assist the expedition. Determined to get what they needed, the Dutch made an assault on the town and tried to take what they needed by force. One hundred and fifty soldiers marched on the fortress overseeing the town and despite its strength the Portuguese fled after a minor skirmish. The Dutch assumed control of the fort but soon found themselves barricaded in with no food. Within a short time they were forced to abandon the stronghold and return to the ship. When the Portuguese governor was informed of the assault he ordered the Dutch to leave.

While the Dutch didn’t acquire supplies at Praia, they did manage to acquire some sort of fever and men started dying, including Mahu. Leadership of the expedition was taken over by Simon de Cordes, captain of Liefde.

With the fleet increasingly hard-pressed for food and many of the crew sick with scurvy, de Cordes decided to sail to Annobon, an island off the West African coast. Yet again they bumped up against the Portuguese. Not trusting the Dutch, the Portuguese on the island tried to prevent them from coming ashore. So what did the Dutch do? Since it had worked so well at Praia, they stormed the island only to find that the Portuguese and their native allies had set fire to their own houses and fled into the hills.

The expedition left Annobon in January 1599 and made it to the Magellan Strait by early April. By the 18th, the Dutch had reached Penguin Island where they massacred about 1400 penguins before continuing down the strait to Mussel Bay.

On May 7th they headed to an island in the south to search for seals but instead found canoes filled with “savages” with ‘long reddish hair’ who were unfriendly and ‘through stones so heavily’ that the Dutch were afraid to go ashore. Those that did go ashore apparently didn’t survive long as the “naked assailants” captured and killed at least five Dutch sailors. At one point the natives attacked the ships with ‘fierce shrieks’ and de Cordes ordered his men to fire upon them to drive them back to shore.

Adverse winds made transiting the strait difficult, but with food (read “meat”) fairly plentiful de Cordes apparently wasn’t inclined to leave the strait. The expedition’s pilot, William Adams, stated “many times in the winter we had good wind to go through the strait, out General would not.” They expedition ended up wintering in Cordes Bay for four months which is really astounding because the strait has been described as “an inconceivable labyrinth of tortuous, storm-swept waterways” and the weather is described as 300 days of rain and storm while the other 65 are “not pleasant.” Who in their right mind would want to spend a winter there!

The expedition narrative describes the weather as terrible with rain, hail, thunder and wind. Not surprisingly, one-hundred and twenty men died because of hunger and “hardship” (which translates to death by the fierce climate and hostile natives!).

When the expedition finally reached Knight’s Bay on August 2nd they held a service of thanksgiving, buried their dead and erected a memorial plaque. Trying to hold things together, de Cordes created the “Order of the Knights of the Unchained Lion” and knighted some of the men who were lucky enough to survive the ordeal.

Shortly after leaving Knight’s Bay they decided to move the memorial plaque to a better location so de Cordes sent Captain de Weert (Blijde Boodschap) back to get it. When he arrived he discovered the natives had unearthed the Dutch dead and mutilated the corpses. They searched the area for the perpetrators who had desecrated the graves but were unable to find them and returned to their ship without having accomplished anything.

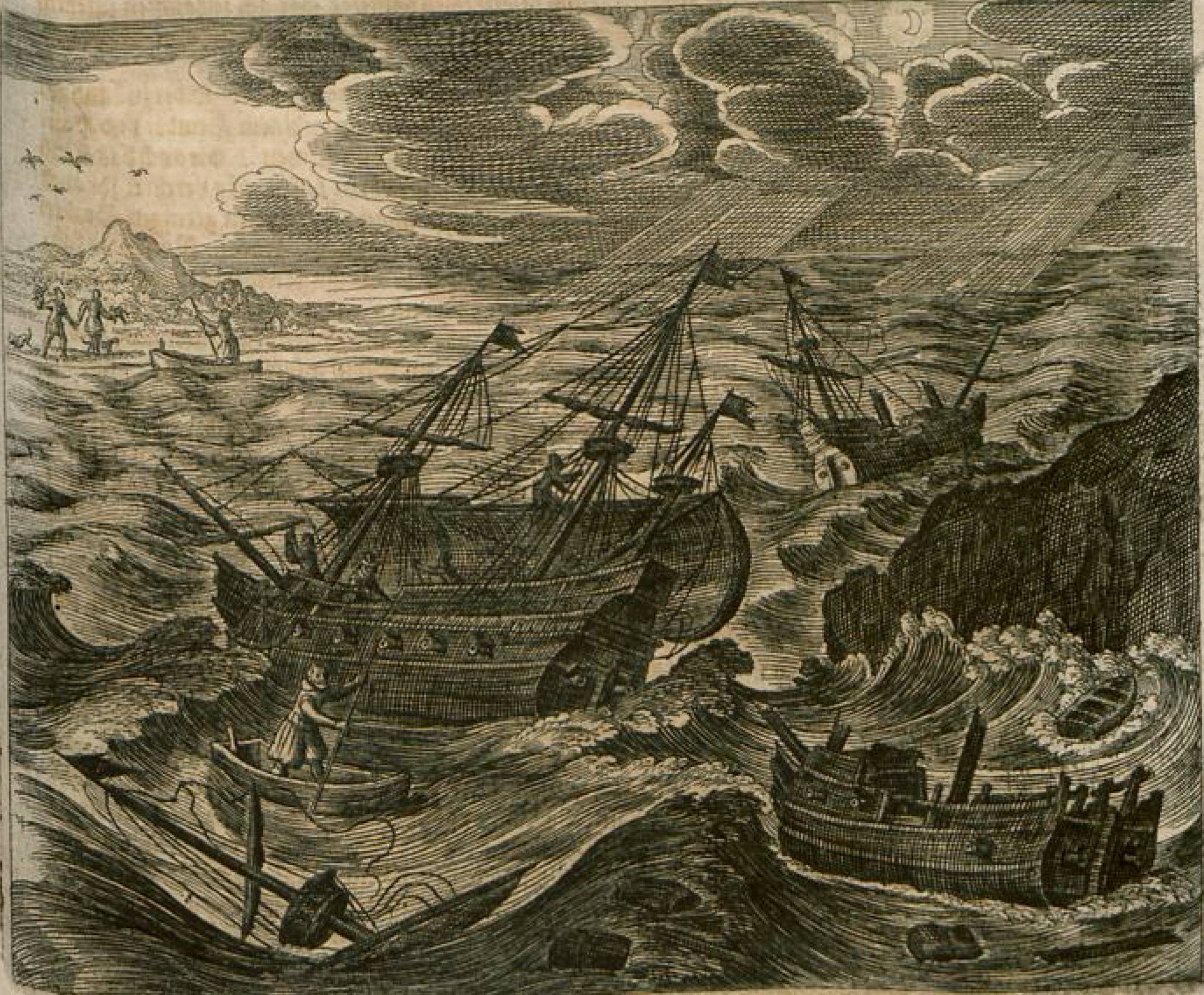

The expedition finally left the strait August 23rd and continued to meet one misfortune after another. In September, the fleet encountered a storm and was scattered. Blijde Boodschap was later captured by the Spanish at Valparaiso. Hoop, along with de Cordes, was lost near Hawaii. Trouwe made it across the Pacific only to be captured by the Portuguese on Tidore in the Moluccas. Liefde was wrecked on the coast of Japan with 24 survivors, one of whom, William Adams, remained as a trader and personal advisor to shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu (which is actually the start of a nearly two decade monopoly on trade between the Dutch and the Japanese).

Geloof, by this point captained by Sebald de Weert, spent a whopping 24 days in the Pacific before being blown back to the strait. Amazingly Geloof encountered another Dutch expedition under Oliver van Noort in the strait. They tried to join van Noort’s fleet but the bottom of the ship was so heavily encrusted with barnacles and weed they couldn’t keep up so de Weert turned the ship around and returned to Holland. The ship reached the Netherlands in July 1600 with only 36 of her original 109 crewmen. They did, however, manage to discover the Falkland Islands on the way home!