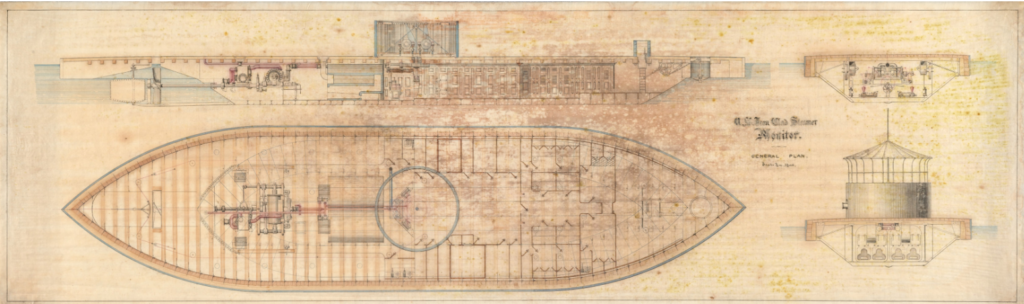

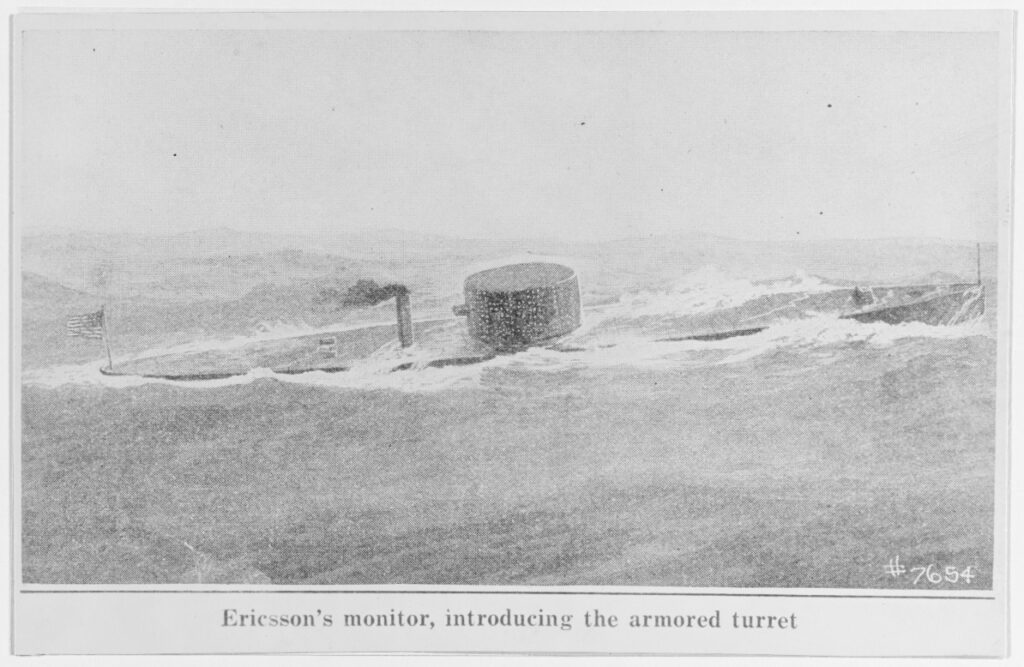

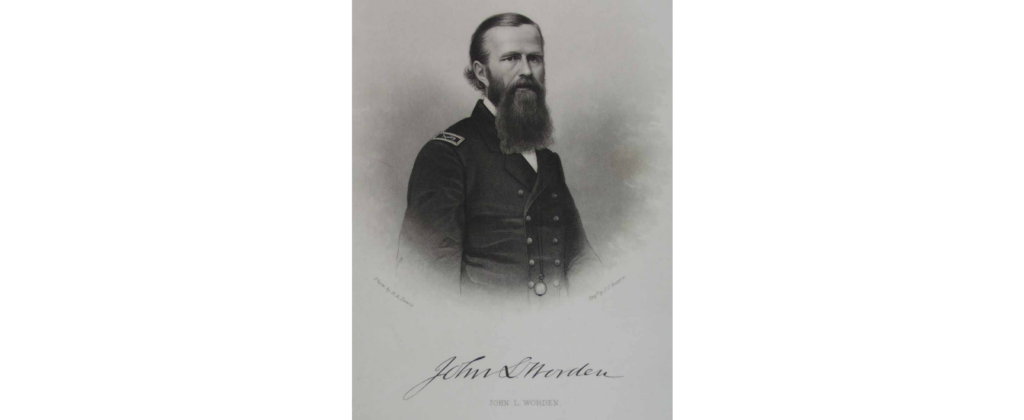

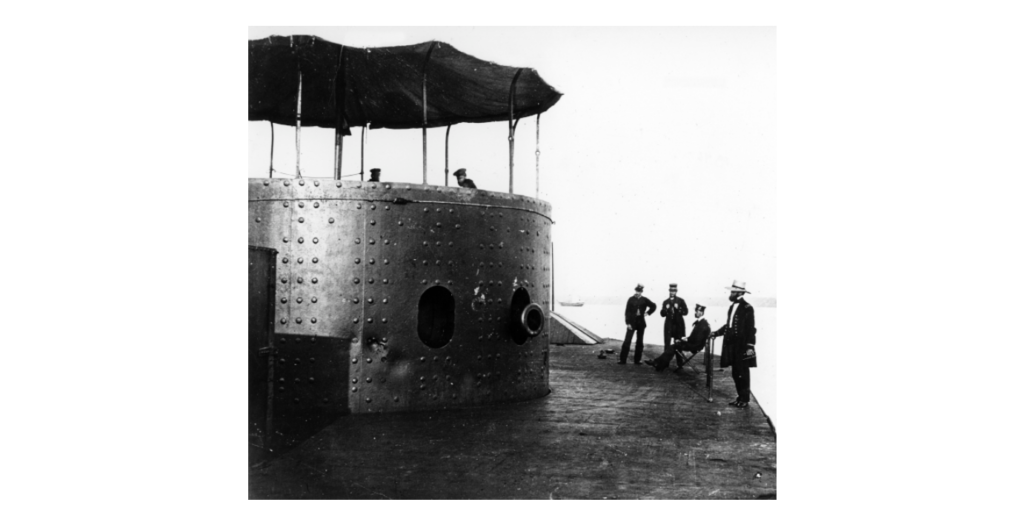

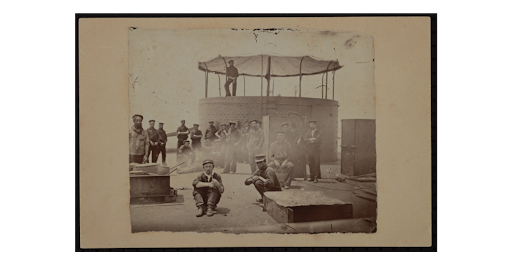

USS Monitor was considered the strangest craft that a sailor’s eyes ever looked upon when the ironclad was launched. It was only 173 feet in length with a 10.6-foot draft. The iron vessel only had a freeboard of eight inches. Since the ironclad was an experiment and totally different from any other naval ships afloat, Lieutenant John Lorimer Worden, USS Monitor’s captain, sought only volunteers to join the crew. Worden went aboard USS North Carolina and Sabine to identify men to crew the ironclad. The response was overwhelming. Few of the recruits had any prior sea service coming from farms and as immigrants from Europe. All were shocked when they reached Monitor.

First Impressions

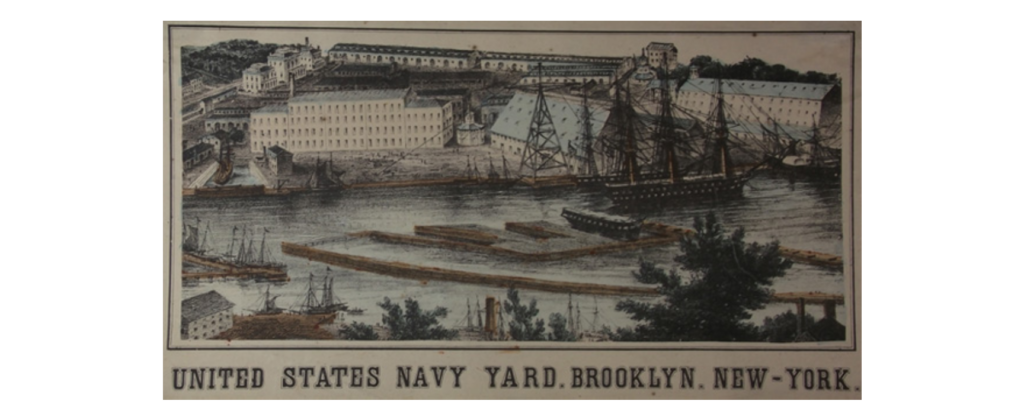

John Driscoll, a 1st class Fireman, shipped on the ironclad on March 6, 1862, as ship’s number twenty. Driscoll later recalled: “While we were lying at the navy yard at Brooklyn, NY, prior to starting for Hampton Roads, VA, all manner of uncomplimentary and satirical remarks were made with regards to her fate[.] When she got to sea one declared …the first heavy sea to wash her decks would swamp her for how could such a mass of iron float if it once got under water[.] Another old sea dog who had followed the sea all his life remarked that if she got into a fight any ordinary ship would run over her with ease, or if boarded by a strong party they could wedge the turret and work the guns in such cramped quarters. On one occasion an old seaman said to the writer in a very solemn and prophetic tone that thing you are going in will never stay up long enough to get out of sight of Sandy Hook. You fellows certainly have got a lot of nerve or want to commit suicide one or the other.” [1]

These comments, as well as the very sight of the low-lying warship, virtually awash with the sea in calm water, and the unusual living space below the waterline prompted several seamen to desert shortly after they arrived on Monitor. Master’s Mate George Frederickson noted in Monitor’s log on March 4, 1862, “Norman McPherson and John Atkins deserted taking the ship’s cutter and left for parts unknown so ends this day.” Coal Heaver Thomas Feeney deserted seven days after he enlisted on the very day he arrived on Monitor. The very thought of going to sea in Monitor prompted Fireman Hugh Fisher and Ship’s Cook Henry Sinclair to desert before the ironclad left port. Seaman Frank A. Ridley was a sailor from Philadelphia. He deserted on February 21 and, using his alias Frank Reyday, he enlisted again to serve as a gunner’s mate on USS Princeton. Many sailors would use an alias in case they did not like their new captain, ship, or crewmates. With a different name, a sailor could just disappear into the vastness of America. [2] Although they did not desert, senior enlisted men like Wells Wenz (Boatswain’s Mate John Stocking) and Samuel Lewis (Quartermaster Peter Truscott) all used false names when they joined the Navy.

Rough Conditions

Despite the many temptations or reasons to desert, many of those who volunteered did so as a sense of duty and also as an opportunity to find a place in their new nation as an immigrant. Many wished to preserve the Union, while others wanted to end slavery. Even though most crew members had high ambitions, life aboard Monitor was filled with dangers, discomfort, and disappointments, which prompted many to desert when they had an opportunity to do so. The first deserters did so probably because they had a fear of combat in an experimental ship or simply considered the novel design too dangerous to put to sea.

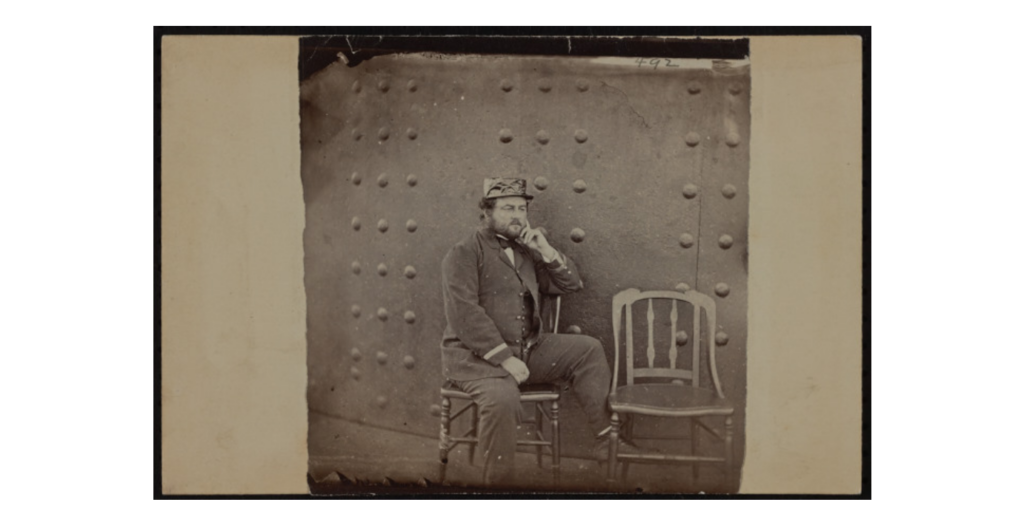

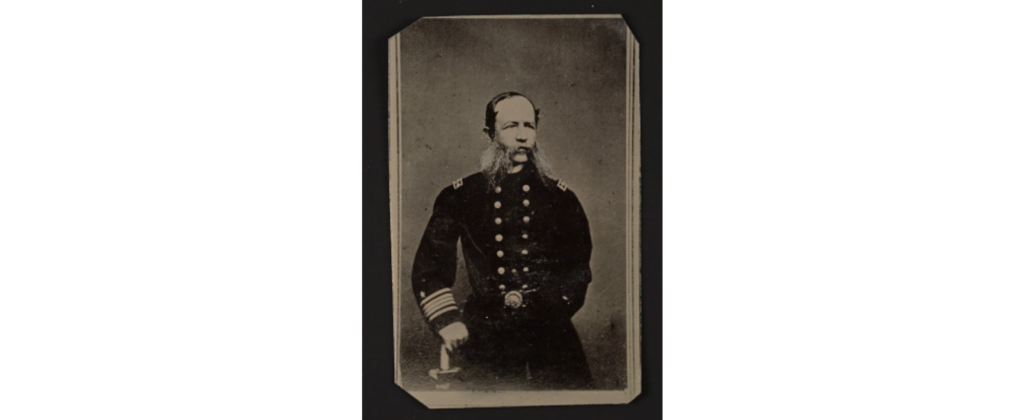

Many were overwhelmed by the rigors of naval service, especially while serving under a difficult captain. When Lieutenant William Jeffers assumed command of Monitor, many were impressed. Samuel Dana Greene wrote his parents that “Mr. Jeffers is everything desirable, talented, educated, and energetic and experienced in battle.” [3] Jeffers would soon lose any esteem held by the officers and crew for him. Paymaster William Keeler would later state in a letter to his wife that things “don’t go as smoothly and pleasantly on board as when we had Capt. Worden. Our new Capt. is a rigid disciplinarian, quick imperious temper and domineering disposition….”[4] Fireman George Geer called Jeffers “a dam’d old hog,” [5] and the other crew members actually wrote their former captain, Lieutenant John Lorimer Worden, on April 24, 1862, addressing “Our Dear and Honored Captain.” The letter continued “These few lines is [sic] from your own crew of the Monitor with there [sic] kindest Love to you[,] Hoping to God that they will soon have the pleasure of Welcoming you back to us again Soon…[S]ince you left we have had not pleasure on Board of the Monitor.” This passionate yet rough-hewn request was signed: “We remain until Death your Affectionate Crew The Monitor Boys.” [6]

Monitor’s crew served in a battle zone from March through August 1862. They suffered from a lack of vegetables and other fresh foods, boredom, mosquitos, sickness, and extreme heat. Monitor was in the James River to protect Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac while camped at Harrison’s Landing. This meant that Monitor’s crew was constantly at combat readiness. These conditions were enough for men to wish to desert; however, there was no place for a Union sailor to go in enemy’s territory. Instead, they had to suffer through the autocratic tendencies of their gouty commander. William Keeler observed one ship inspection when Lt. Jeffers “passes slowly in front of the lines of men looking closely at their dress, appearances- &—’Jones why are your shoes not blackened?’ Jones having no good excuse, the Paymaster’s steward is ordered to stop his grog for a day or two. Jeffers dressed down one enlistmen stating ‘What is this man’s name?’ ‘Smith, sir’– ‘Well have his grog stopped for a week for coming to inspection without a cravat.’ ‘Do you belong to this ship?’ ‘Yes sir’– ‘Well you are a filthy beast, a disgrace to your shipmates, the dirt on you is absolutely frightful. If I sso again I will have the Master at Arms strip you & scour you with sand & canvas.’”[7]

Jeffers’ moods and meanness only added to the difficult and uncomfortable life on the ironclad. The ventilation was poor and the crew members suffered from the intolerable heat and humidity. George Geer was well aware that Monitor “was not properly ventilated for men to live in during hot weather….” [8] The crew was not allowed to forage for food and deliveries of fresh vegetables, meat, and other stables were slow in reaching Monitor. The transports had to come from Hampton Roads to feed the Army of the Potomac as well as the US James River Flotilla. A general feeling of being isolated, so far from home, and surrounded by enemy territory made many sailors yearn for freedom from their iron coffin. Yet, they had nowhere to escape. Likewise, when Monitor was restationed to Hampton Roads, the region was a major Union military base. Accordingly, the crew was trapped aboard their ship with no viable opportunities to desert. The men could be thankful for the better weather and food. They had also been freed from the tyrannical rule of Lt. Jeffers. Jeffers was reassigned, and Commander Thomas Holdup Stevens, Jr. Became Monitor’s new commander. Stevens was soon replaced for drunkenness by Commander John Pyne Bankhead. Bankhead was an outstanding officer and treated the crew fairly. This improvement was a positive change. Still there were many men who wished to break out from their iron cage and simply waited for the right opportunity to do so.

Desertion and Sickness During the Furlough

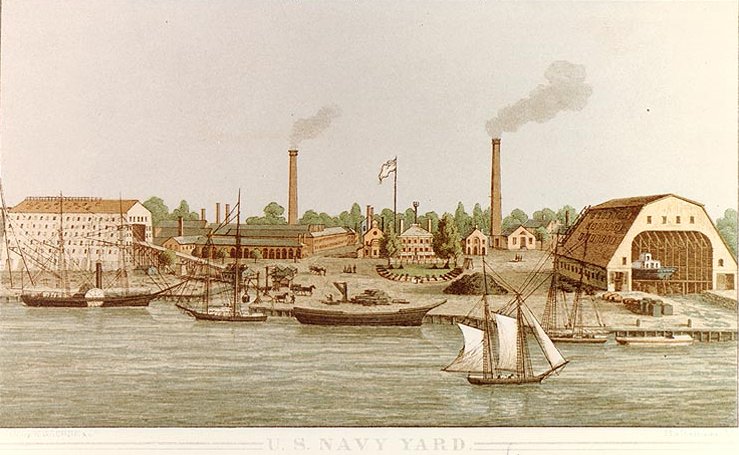

On September 30, 1862, Bankhead was ordered to take Monitor to the Washington Navy Yard for repairs. Consequently, the officers and men were sent aboard the steamer USS King Phillip when Washington Navy Yard workers took over Monitor for repairs. The officers and men were not destined to remain aboard the receiving ship for long. Captain Bankhead immediately went on leave and left behind authorization that officers and crew were to be allowed two to four weeks of leave. Paymaster Keeler would be one of the last officers to depart, as he had the responsibility to pay off the men with several month’s worth of earnings. Most of the men had been away from home for over eight months and were overjoyed that their furlough freed them from their cramped quarters on Monitor.

George Geer noted that more than 200 recruits arrived at the Washington Navy Yard on November 2, and he speculated that “some of them I suppose will go on us, as ten of our men have not come back yet.”[9] Jacob Nicklis was one of the new recruits for Monitor. Ordinary Seaman Nicklis had just been transferred to Washington Navy Yard for assignment when he wrote to his father: “The Monitor lies in the Yard at present for repairs & she will probably take some of us, as her crew ran away when they landed in the Yard on account of her not being so sea worthy. But since then they have altered her so I think that there will be no danger.” [10]

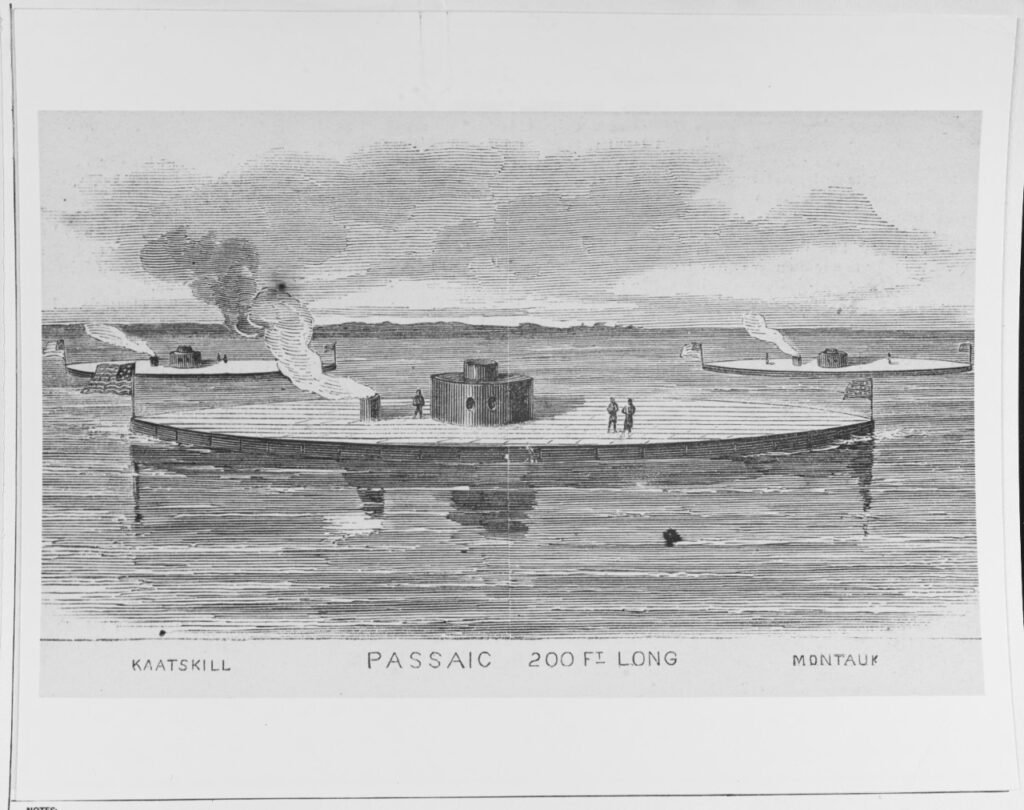

Many Monitor Boys simply did not return from their furloughs. Several of these men were unable to get back to Monitor due to illness or misfortune. Coal Heaver William Durst was given two weeks liberty and spent his leave first in Philadelphia and then in New York City, where he became ill. He claimed his illness to be typhoid fever, but he also believed that he was “sick for some trouble to my heart and stomach, contracted from the bad air on the Monitor.” Regardless of the cause, he was unable to return to duty and apparently did not know what to do. Instead of returning to Monitor, Durst went out drinking one day shortly thereafter: “I was taken in charge of ‘a runner’ and the next thing I knew I was on board the North Carolina. I asked for an explanation, and was informed that I had been shipped under the name of Walter David, that there was nothing for me to do but to serve out my enlistment for one year.” [11] William Durst’s ‘WD’ tattoo on his forearm had earned him the alias ‘Walter David.’ David (Durst) was then detailed to serve aboard the Passaic-class monitor USS Catskill.

In his post-war quest for a pension, he had to secure witnesses to prove that Durst and David were one and the same. Sickness was why he could not return to the ironclad when his furlough expired. Durst was listed as a deserter from Monitor on November 6, 1862. Unwittingly, after an evening of drinking, Durst reenlisted under the name of Walter David and then shipped aboard the monitor USS Catskill. Fortunately, several men who had served on Monitor with him also served on Catskill. Brooklyn Navy Yard. Seaman Hans Anderson noted that “I did not see until I saw him on the KAASKILL [sic] at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. I knew him as soon as I saw him and called him Durst. He laughed and said that that was his name once, while on the LITTLE MONITOR but now they call me Walter David….I called him Durst …and he was sometimes called the Dusty Jew.”[12]

Many claimed that Durst had a “Jewish nose.” This feature enabled his former shipmates to identify him; however, the unusual bend of his nose was due to it being broken, not by his being a Jew. Although Durst said he broke it aboard USS North Carolina, his brother Louis stated that Durst’s nose had been broken as a child when he fell out of a tree. The charge of desertion was dropped, as the Navy Department noted that “Durst was of foreign birth and unaccustomed to the ways of his adopted country” and that he had “in fact served in the navy during almost the entire period of the Civil War.” Durst maintained great pride in his service aboard Monitor and began to embellish his record as the years went by. He stated that he was on Monitor the night the vessel sank. Although Durst was not there, he continued to state that he was, because he realized the ironclad’s sinking to be an even more heroic event than the battle itself. Durst continued to promote his service on Monitor by attending events, often stating that he was the last survivor (he was not) of Monitor. During a GAR encampment in Washington, D.C., Durst can be seen in a photograph supposedly wearing the same uniform he wore on Monitor, saluting President Woodrow Wilson.[13]

Another tale of apparent desertion was Seaman Hans A. Anderson. Just before he was due to return to the Washington Navy Yard from New York City, Anderson “fell in with some men and went into a rum hole, and took a glass of beer which was evidently drugged.” [14] He soon found himself shanghaied on an unknown barque sailing for London. Anderson eventually made his way to a U.S. consul, returned to the United States, and surrendered himself on February 2, 1863. He was allowed to return to duty and, except for loss of pay while absent from duty, he was not penalized for his misadventures.

Carpenter’s Mate Derrick Bringman, Quarter Gunner John P. Conklin (Conking), Coxswain Daniel Walsh, Hospital Steward Jesse M. Jones, and Seaman Thomas Longhran just did not appear on the ship’s muster roll on November 6, 1862, and disappeared from naval records. First-class Fireman John Ambrose Driscoll not only deserted his wife Abigail Sweeney and children when he emigrated to America from Ireland, he also deserted from Monitor. Some sense of honor still remained within his soul as he re-enlisted less than a month later aboard USS Connecticut. Anton Basting also was listed as a deserter. This decision later haunted him as his pension was denied because of him not returning to Monitor when his leave expired on November 7, 1862.[15]

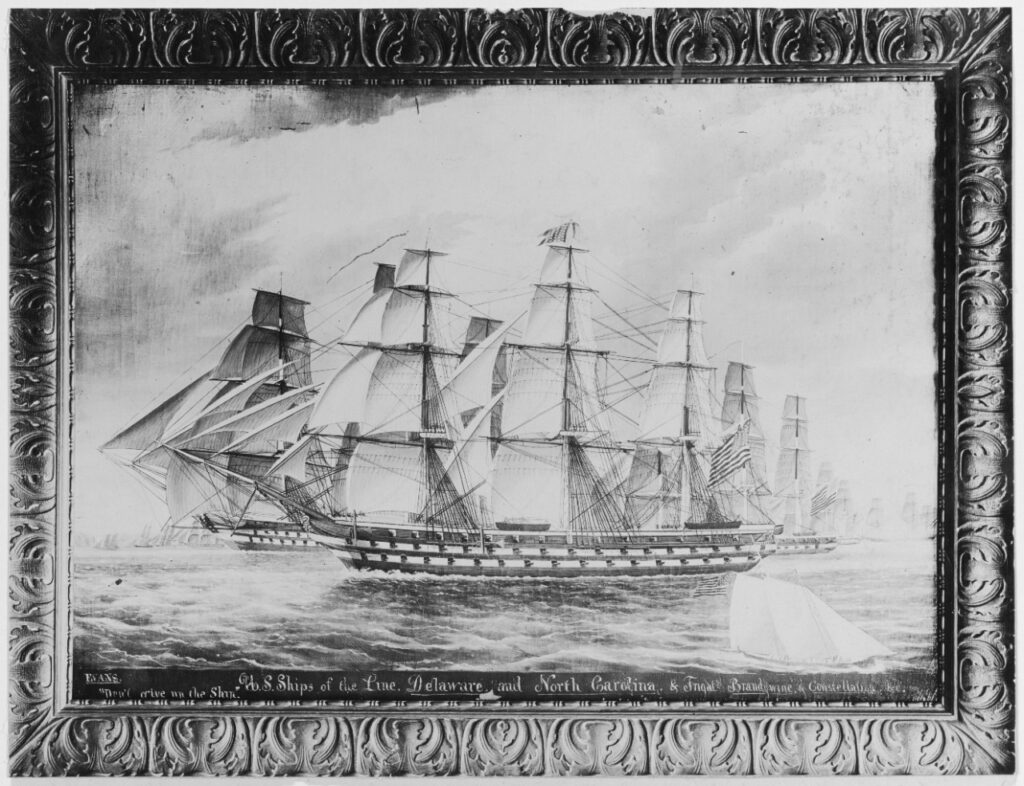

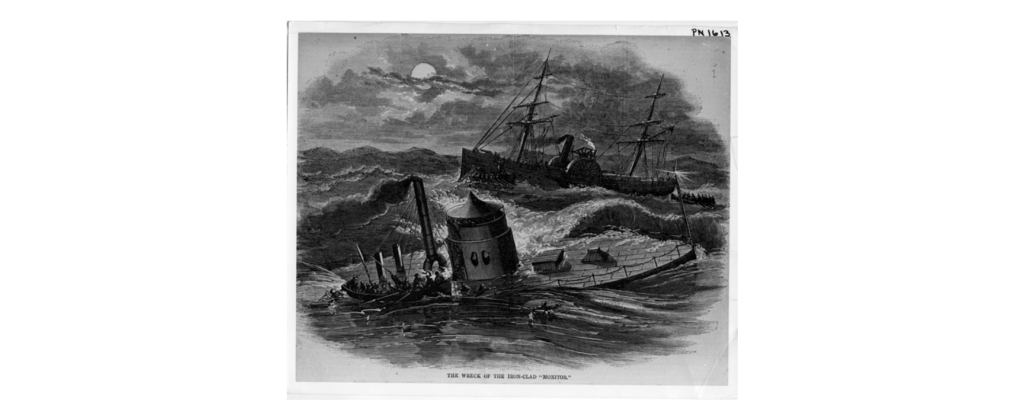

Following Monitor’s tragic sinking on December 31, USS Rhode Island returned to Hampton Roads with the ironclad’s survivors where they disembarked. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles ordered on January 4, 1863, that all of the survivors who had served on the ironclad from its first muster through to its sinking were granted “a two weeks leave, with 20% of all they have due to them,” and they were given to “return to the receiving ships nearest their residence.” [16] Weather and wartime conditions limited travel, so most of the ‘Monitors’ were initially detailed to USS Brandywine. This 44-gun frigate had been launched on June 16, 1825. The old warship had been redesignated as a storeship for the North Atlantic Blocking Squadron, Hampton Roads Station. Conditions aboard Brandywine were difficult for the former Monitor Boys. The men were not immediately rationed new clothing or blankets. They were cold, depressed, and demoralized.

George Geer even thought about deserting while at the Norfolk (Gosport) Navy Yard and noted in a letter to his wife that he hoped he would be given liberty and a reassignment to a receiving ship in New York. He sadly commented, “I very much doubt their ever seeing any of us again if we once get outside of the Navy Yard Gate.” Geer thought most of the sailors and soldiers were against the war and hardly one but desert the first chance.”[17] Many did. Christy Price, Robert Quinn, William Remington, Henry Harrison, Anthony Connoly, William Marion, and William Scott all deserted within a year of Monitor’s demise. One hundred and three officers and crew were assigned to Monitor over the ironclad’s brief existence. Of these men, 13 deserted while the ship was in the Washington Navy Yard. Another 10 would escape their service throughout 1863 when assigned to other ships. Navy life was difficult, and for those who survived the ironclad’s sinking, many crew members had fought two major engagements and escaped death on December 30-31, 1862. These men had all seen enough of the Civil War at sea.

Endnotes

1. Irwin Mark Berenrt, The Crewmen of the USS Monitor: A Biographical Directory.. Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1985, p. 30.

2. John V. Quarstein, The Monitor Boys: The Crew of the Union’s First Ironclad, Charleston: The History Press, 2011, p. 43.

3. Samuel Dana Greene, “Manuscript,” U.S. Naval Academy Trident, Spring 1942, pp. 42-44.

4. Robert W. Daly, ed., Aboard the USS MONITOR: 1862: The Letters of Acting Paymaster William Frederick Keeler, US Navy, to his wife Anna, Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute Press, 1964, p. 53.

5. William Marvel, ed., The Monitor Chronicles, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000, p. 28.

6. Worden Papers, Lincoln Memorial University, Harrogate, Tn.

7. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, p. 151.

8. IBID., p.72.

9. Marvel, The Monitor Chronicles, p. 200.

10. The Letters of Jacob Nicklis, The Mariners’ Museum and Park, Newport News, Virginia.

11. Berent, p.34.

12. IBID., p.79.

13.Quarstein,

14. IBID., p. 9-10.

15. Quarstein,

16. U.S, Department of the Navy, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion,ser. 1, vol. 8, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1899, p.341.

17. Marvel, The Monitor Chronicles, pp. 238-241.