Introduction

Sometimes museums acquire objects only to discover that what they thought they were is not, in fact, what they are. This frequently happens with paintings, especially if there are no identifying marks or titles and their history has been lost to the sands of time. When a painting’s history is forgotten, it takes extensive research to identify the scene or suggest a theory about what, or who, the painting shows. This is called an attribution. Sometimes attributions are spot on, sometimes they are way out in left field, and sometimes attributions don’t even fall within the ballpark of reality! For 90 years, curators at the Museum have struggled with the attribution of one such painting in the Collection, a portrait showing a 17th-century family. Over the years as many as six different suspects have been suggested as the portrait sitters. In March, yet another curator (me) decided to reopen this cold case and undertake yet another investigation. This time, the resulting reattribution may have finally cracked the case!

The Cold Case Opens

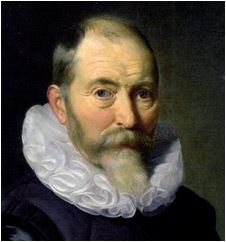

In March of 1934, The Mariners’ Museum acquired a monumental (9’ high by 7’ wide) portrait of a 17th-century family. When it was accessioned into the Collection, the painting was believed to depict explorer Henry (or Hendrick) Hudson and his family.

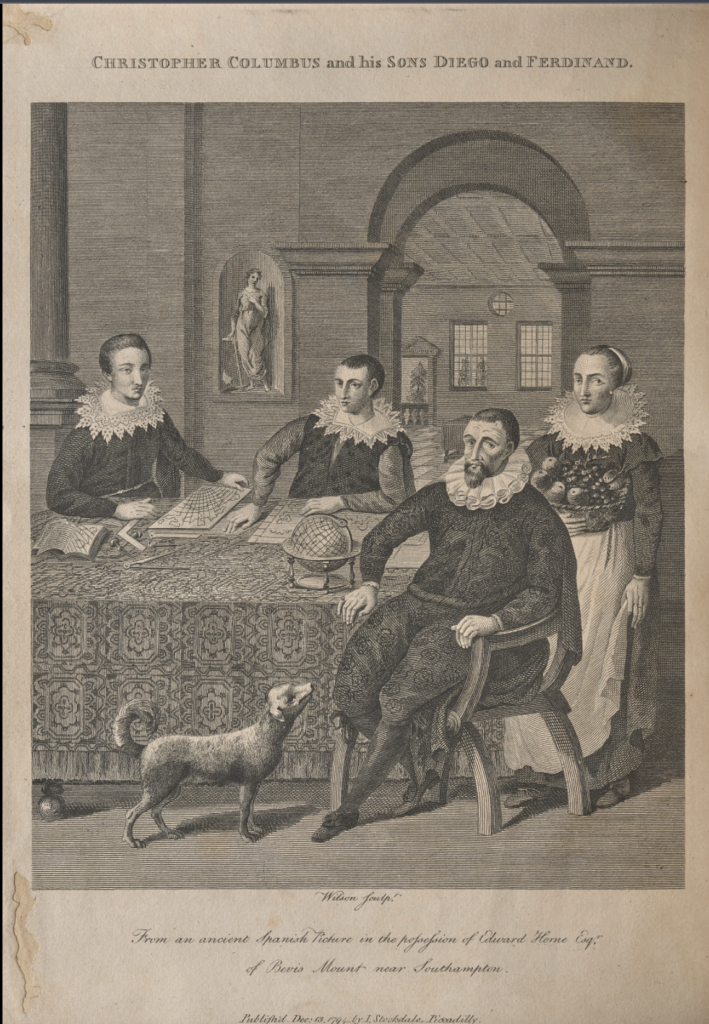

A year later, an engraving showing an eerily similar image was found as the frontispiece of the second edition of volume 2 of Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies (published in 1794). A publication note accompanying the image stated ‘From an ancient Spanish picture in the possession of Edward Horne, Esq. of Bevis Mount near Southampton.’ The image, which was titled Christopher Columbus and his sons Diego and Ferdinand, immediately called the attribution to Hudson into question. Museum staff realized they had a crime of false attribution on their hands and began an in-depth investigation.

The investigation began with Bryan Edwards, who presented his case for attributing the painting’s suspects to Christopher Columbus and his sons on page liii of volume 1. In his testimony, he states:

The picture from which this engraving is made, bears the marks of great antiquity, and from the words Mar del Sud on the chart represented in it, it is known to be Spanish. The principal figure is certainly Columbus. And the two young men are believed to be his sons, Diego and Ferdinand, to whom Columbus seems to point out the course of the voyage he had made. The globe, the charts, and astronomical instruments support this conjecture, and the figure of Hope, in the background, alludes probably to the great expectations which were formed, throughout all Europe, of still greater discoveries. From the mention of a Southern Ocean, imperfectly and dubiously represented, (as an object at that time rather of search than of certainty) there is reason to believe that the picture was painted immediately on Columbus’s return from his fourth voyage, in 1504, because it is related by Lopez de Gomera, a co[n]temporary historian, that the admiral, when at Porto Bello, in 1502, had received information that there was ‘a great ocean on the other side of the continent extending southwards’; and it is well known, that all his labours afterwards, in the fourth voyage, were directed to find out an entrance into the Southern Ocean from the Atlantick [sic]; for which purpose he explored more than 300 leagues of coast, from Cape Gracios a Dios to the Gulph [sic] of Darien; but the actual discovery of the South Sea was reserved for Vasco Nunez de Balboa. The age of Columbus’s sons, at the time of his return from his fourth voyage, corresponds with their appearance in the picture.

As I thought about Edwards’s testimony several comments — snarky ones — popped into my head:

- The original picture “bears the marks of great antiquity.” Pardon me, but the age of the painting doesn’t provide any evidence that the portrait shows Columbus’s family.

- Edwards says that the words “Mar del Sud” on the map on the table indicate the painting is Spanish. First of all, there are no words on the map in the engraving so Edwards must be talking about words on the painting. If so, he is wrong, the words on the painting are not “Mar del Sud” but “[Mar] del Zur” which is German.

- Edwards continues with “the principle figure is certainly Columbus. And the two young men are believed to be his sons”— well this is just a completely unfounded statement made with no supporting evidence whatsoever.

- He says that the person identified as Columbus “seems to point out the course of the voyage he had made.” Really? Can you see any evidence of that in this image? I can’t.

- Edwards continues “The globe, the charts, and astronomical instruments support this conjecture, and the figure of Hope, in the background, alludes probably to the great expectations which were found throughout all Europe of still greater discoveries.” Again, these statements are just pure assumptions; and by the way, there are no astronomical instruments in the engraving or the painting.

- Edwards then says that the reference to a Southern Ocean reflected Columbus’s search during his fourth voyage for a route through the South American continent to a southern ocean, a thing that he had heard rumors of but that no one had ever seen. Edwards further conjectured that the mention of this ocean indicated the painting had been created in 1504 even though the Pacific wasn’t discovered until 1513. If his dating is accurate how would the artist have known what shape to paint the Pacific or South America?

- Edwards’s date of 1504 also completely ignores the fact that the portrait sitters are wearing distinctly 17th-century clothes.

- And finally, Edwards felt that the physical description of Columbus given by his youngest son years after his death corresponded with the painting: “The Admiral was a well built man and of more than medium height; a long face, the cheek bones a little high, without inclining to be fat or thin; with aquiline nose, light eyes and the whites of bright color; in his youth he zhad blond hair, but at thirty years of age already had gray hair.” I think if you walk down the street, this description would fit half of the men you passed and we wouldn’t call them Columbus.

Obviously, my undisguised mockery of Edwards’s “evidence” has already given you an inkling that I don’t buy the attribution to Columbus for a second. And I’m not alone. Author and expert witness Néstor Ponce de León thoroughly discredits Bryan’s attribution in The Columbus Gallery (published in 1893). In his testimony, he states firmly that “a mere glance is sufficient to convince us of the fallacy, as the types, the dress, the accessories and other particulars, so that this picture must have been painted at least 100 years subsequent to the date claimed…[and] had no intention of portraying so an illustrious a family, but probably some rich Dutch merchant or planter and his sons.” Ponce de León wraps up his commentary by stating, “I will only say that this is the ugliest alleged portrait of him [Columbus] I have ever seen.” Weeeeelllll, okay then. Suspects Christopher, Beatriz, Fernando and Diego are firmly ruled out. Fortunately, Museum staff at the time felt the same way and stated that “further appraisal of the painting” was needed and that “reference to what other critics have said” must be heeded before a firm attribution to a new suspect could be made.

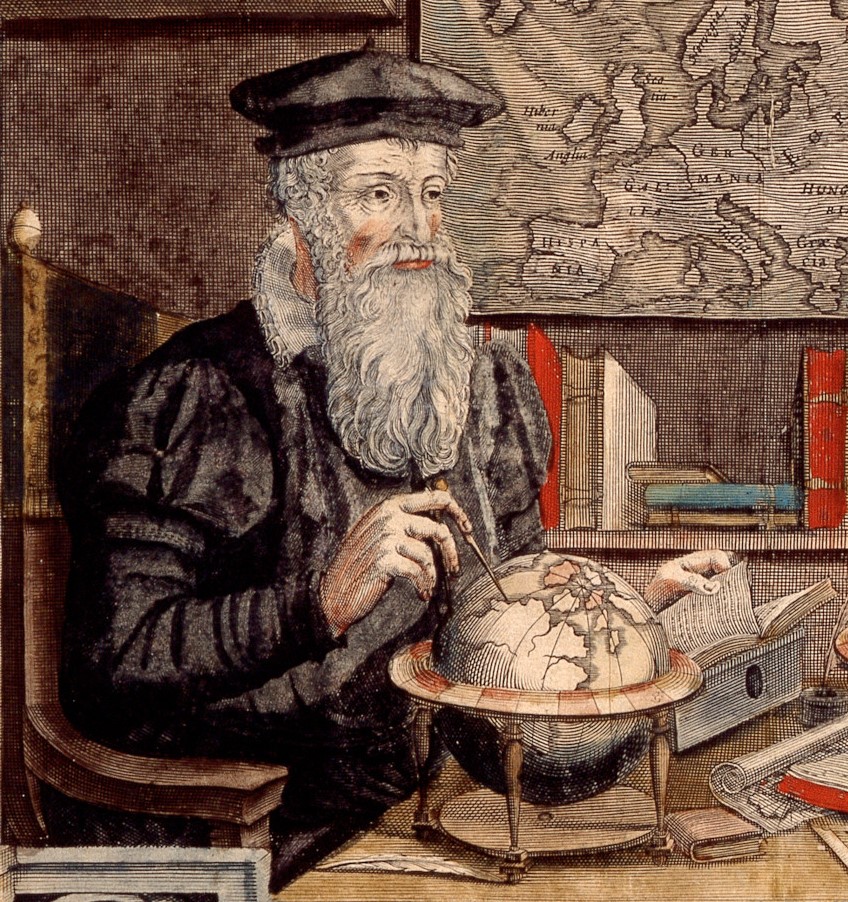

In April 1935, Curatorial Scene Investigator Captain Roger Williams, a vice president of Newport News Shipbuilding in New York1, appears to have taken a photograph of the painting to the Hispanic Society of America to get their opinion of the case. Witness Elizabeth du Gué Trapier, curator of paintings and drawings, immediately suggested that the suspect was a cartographer and that the painting dated to the first half of the 17th century. She felt the two young men were engaged in drawing Mercator charts. She then suggested that an attribution to Gerard Mercator, whose three sons assisted him in his work, could be considered, but that if it was Mercator, it would have to be a later representation of him, as he died in 1594. She also said the image of the older man does have some resemblance to an engraved image of Mercator made in 1574 but this investigator doesn’t see it!

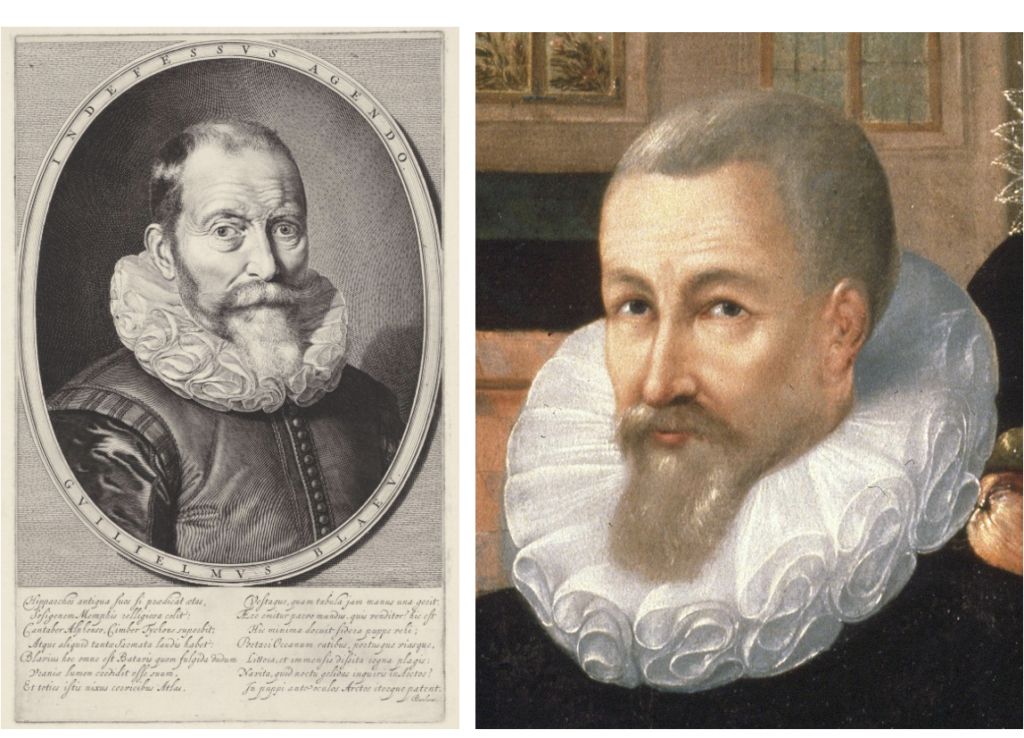

Witness Trapier also suggested that cartographer and publisher Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638), who had two sons who followed him into his profession, could also be considered. In Captain William’s opinion, however, there was “little resemblance between the so-called Columbus and the only portrait” the Hispanic Society had of the new potential suspect (Blaeu).

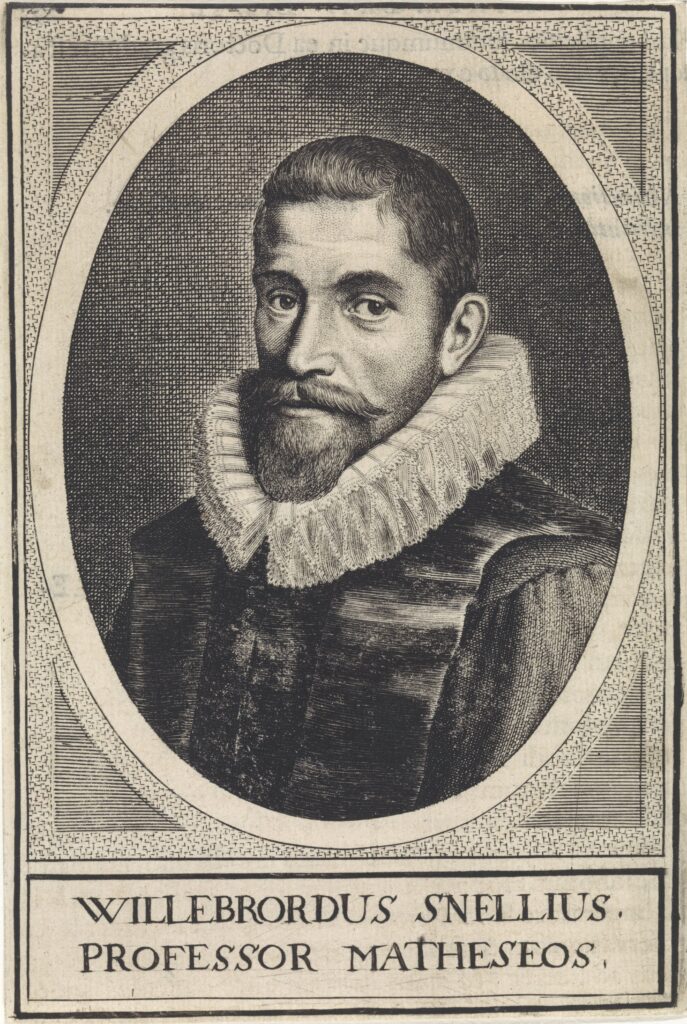

Around the same time, a photograph of the painting was sent to Curatorial Scene Investigator Dirk Verwey2 in Rotterdam for his opinion. Verwey agreed that the image illustrated a Dutch cartographer or mathematician from the first part of the 17th century. He went to the local maritime museum and looked through a portfolio featuring potential suspects (17th-century cartographers) and “was struck by the likeness of face of the bearded gentleman” to engraved images of Willebrord Snellius (alias Snel van Royen, 1580-1626). Snellius was a Dutch astronomer and mathematician who conducted experiments aimed at measuring the circumference of the earth. He also produced a new method for calculating Pi and rediscovered the law of refraction among other accomplishments.

In an effort to substantiate his attribution to Snellius, Verwey contacted a number of experts in the Netherlands3. Besides agreeing that the painting was Dutch or Flemish and that it dated to the early 17th century, none were willing to firmly attribute the family as Snellius and his surviving children. I don’t blame them. Snellius seems younger than the man in the painting (and he died when he was 46). And if you look at the line of suspects in Athenæ Batavæ, you could make a case for any of the depicted men as being the older man in the painting. The Dutch clearly had a preferred hair and beard style in the early 17th century!

At this point, the trail went cold. The investigation stalled until October 1953, when Curatorial Scene Investigator Harold Sniffen reopened the case. Sniffen contacted expert witness Gertrude Tomsend, curator of textiles at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, about the lace collars worn by the suspects. Ms. Tomsend provided some expert discussion of the collars (the lace on the young men’s collars is point coupé) and opened a new line of investigation when she commented, “I believe the carpet on the table is Spanish. Knotted carpets from Spain must have been well known in the Netherlands.” Unfortunately, none of the information proved helpful in firmly identifying the suspects in the painting.

The case was picked up again in 1974 when a new Curatorial Scene Investigator named John Sands began investigating the painting. He revealed new details on September 17, 1974, when he stated, “One of the items in the picture can be read ‘Zuyder Zee.’ In fact, the presence of a burin [an engraving tool] next to the map leads one to believe that it is a plate in the process of being engraved.” Over the next 15 years or so, Sands discussed the painting with several art history and conservation professionals, but the only new breakthrough in the case was confirmation that Edward Horne was, in fact, a real person who lived at Bevis Mount in the late 18th century (this refers to the 1794 engraving in Bryan Edwards’s book). This evidence solidified the investigative staff’s opinion that the painting was original (despite heavy restoration) and not an old fake or copy. The attribution of the main suspect in the painting to Snellius remained, but I don’t think any of the investigators were convinced.

Again the trail went cold until 1991, when Curatorial Scene Investigator Lisa Royce, in preparation for a new Age of Exploration gallery, contacted about 20 museums in Europe and the United States in an effort to confirm the suspect’s attribution to Snellius and determine the artist. Only a few replies were received and all they managed to do was further muddy the investigation about the possible suspect4 and the potential provenance of the painting.5

Witnesses Josephine Matthews and David Lyon (the chief of research of the Maritime Research Center) of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich provided several insightful leads for the investigators. First, the globe is Dutch and dates to circa 1610, and is of the sort produced by Willem Blaeu. Second, the suspect at the left is a Dutch engraver/cartographer with his copper plate and engraving tools on the table beside him. For some reason, however, Detective Royse didn’t take the comments to heart and didn’t follow up on the new leads leaving the likely suspects Willebrord Snellius and his family or students.

As the newest Curatorial Scene Investigator, I felt that Matthews and Lyon’s comments had opened the door to a new and possibly correct identification of the suspects in the painting. TWICE someone had mentioned the name Blaeu as a suspect but no one tried to prove or disprove the theory. It’s been 90 years since the Museum acquired the painting and the crime of the misattribution was revealed and 33 years since the last mention of Blaeu as a possible suspect. I figured it was time to reopen the case and settle the question of the suspect’s identity once and for all. My investigation, however, would take a different tack. Rather than look at the people, clothing, or architecture, my investigation would concentrate on the objects sitting on the table. If the globe had been rendered well enough for witnesses to identify it as a Blaeu production, maybe the other items on the table could be identified as well. My theory was that the objects on the table might reveal the identities of our suspects.

Solving The Cold Case Begins

The items on the table include a globe, a map, a copper printing plate, and a small book or atlas showing a map-like image supported by text. The other items on the table included two burins or gravers, a burnishing tool, a pair of dividers, a straightedge and a square, and a tool for drawing curves. Unfortunately, the tools are too generic to help with the investigation. I imagine many woodworkers have those same implements in their toolboxes today.

With the comments of the National Maritime Museum witnesses in mind, I began my investigation with the globe. Since the Museum isn’t lucky enough to own a Blaeu globe, I conducted a quick internet search and it led me to…dare I say it…Wikipedia. Now before you freak out, I agree that the information presented on Wikipedia should be carefully used, but in this instance, the page is a gold mine of photographs that proved to be extremely illuminating. First, there is an engraving of Blaeu that I think resembles the older man in our painting fairly well when you take into consideration the artist’s modest skill and the amount of restoration the painting has received.

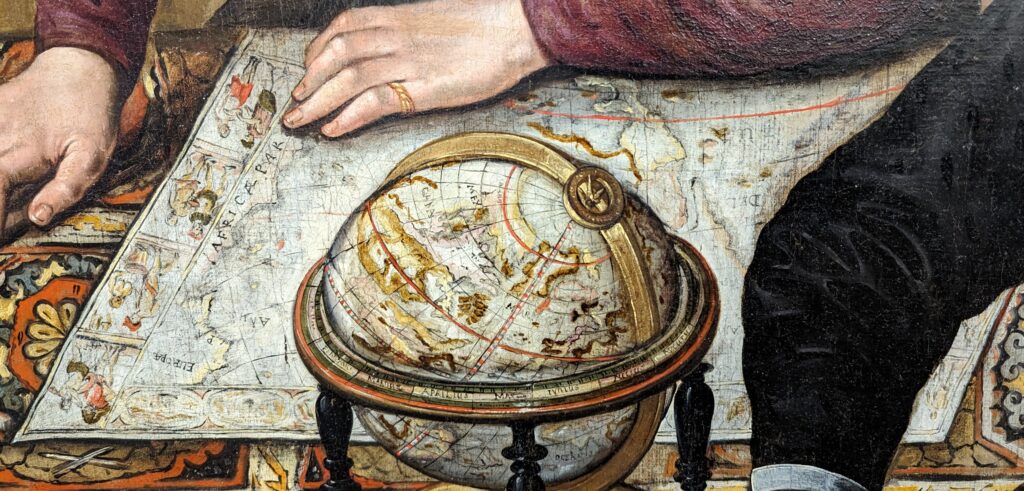

The Globe: Exhibit #1 admitted into evidence

Along with the portrait, the Wikipedia page features a picture of a 16216 nine-inch globe in the collection of Skokloster Castle in Sweden. The globe bears a remarkable resemblance to the globe in our painting. Despite the fact that the painted globe has been rendered by someone of moderate artistic ability, it conveys enough information to facilitate comparisons with the Skokloster globe. In fact, they match well enough that I was able to identify exactly which part of the globe the artist is presenting to the viewer: the continents bordering the Atlantic Ocean. This fact leads me to theorize that the artist was in the presence of a Blaeu globe or had one to use as a model as the portrait was being painted

As the National Maritime Museum experts suggested, the painted globe has a number of attributes typical of Blaeu globes:

- Blaeu globes ranged in size from a single two-inch pocket globe up to 26 inches. When compared against the hand resting next to it, the size of the painted globe seems to fit Blaeu’s six-inch or nine-inch size.

- The painted globe is shown mounted in a Dutch-style stand. The turned wood base ornamented with the small black disks is a typical feature of Blaeu globes. The painted stand is remarkably similar to the stand of the Skokloster globe.

- The brass meridian ring and hour dial and pointer are similar in style to those used on Blaeu globes.

- The meridian line is shown running through Greenland and the eastern side of Brazil which places the prime meridian in the Azores. According to Peter van der Krogt in Globi Neerlandici, this fits with the location of the prime meridian on Blaeu’s six-inch and nine-inch globes (Corvo or Flores in the Azores).

- The letters ‘MAR’ (part of Mare Atlanticum or Mar del Nort) and ‘Oceanus’ (part of Oceanus Aethiopicus) are visible in nearly the same positions as original Blaeu globes.

The Map: Exhibit #2 admitted into evidence

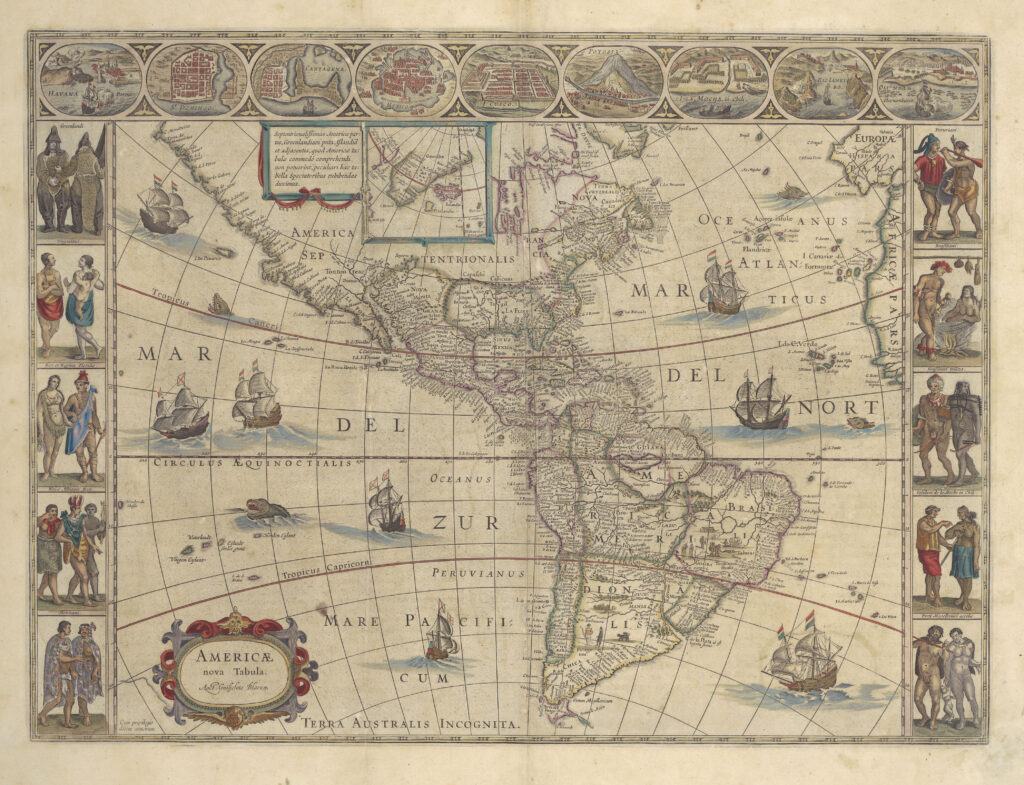

A third image found on Blaeu’s Wikipedia page literally had me throwing my arms in the air in celebration. Of the hundreds of maps produced by Blaeu, the author of the page had chosen to show Blaeu’s map of the Americas titled Americæ nova tabula. It’s no wonder. Dealer Barry Lawrence Ruderman, states that this map is “one of the most sought-after maps of America from the Golden Age of Dutch cartography.” Amazingly, it is the exact map depicted in our painting

In the collection of UTA Libraries Special Collections. Wikimedia Commons.

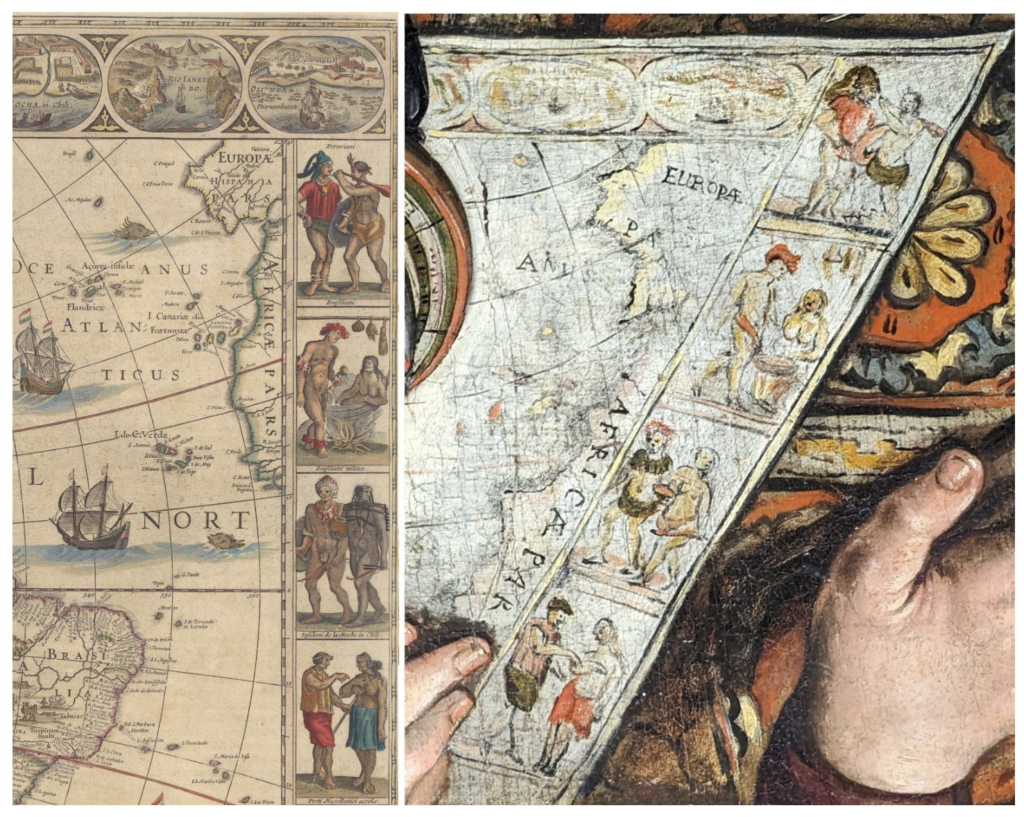

Americæ nova tabula was first produced in 1614 and began appearing in atlases in 1617. It had a long-lived printing life because it is the only Blaeu map to show all of the known regions of North America. It appeared in five versions (states) between 1614 and 1663. One of the most identifiable features of the map is the unique border featuring couples of native North and South Americans and scenes of specific North and South American locations. Even though the map in the painting has been artistically rendered, several parts of it are readily identifiable as depicting Americæ nova tabula.

Comparing the right side of the original map and the painted map, you can see they share a number of attributes:

- Four border images on the right side of both maps depict: Peruviani, Brasiliani, Brasiliani milites, and Insulani de la moche in Chili. The images show couples of South American natives in cultural dress and settings and with implements or items specific to their culture.

- Two border cartouches at the top right corner of each map show ‘Olinda in Pharnambucco’ and ‘Rio Ianeiro.’ Parts of the third cartouche also show similar shapes and coloring.

- Inside the border, the European continent is visible and identified by the words ‘EUROPÆ’ and ‘PA’ (the R is only partially visible on the painted map and may have disappeared during a past cleaning).

- To the left of the European coastline, the letters ‘ANUS’ (laugh — I know you want to) show part of the word ‘OCEANUS’ with the letters ‘OCE’ obscured by the globe.

- Down the right side of the map, the edge of the African continent is visible and identified with the words “AFRICÆ PAR.”

Much of the left side of the map is obscured in the painting, but parts of the North and South American continents are visible beside the globe and around the elbows of two of the suspects. The parts that are visible are clearly recognizable in the original map.

The Copper Plate: Exhibit #3 admitted into evidence

Moving on to the next item on the table, the copper printing plate, you may notice that something is amiss. The artist has chosen to portray the map as a non-mirror image. Copper printing plates were engraved as mirror images so that when a print was made from the plate, the printed text and images appeared in the correct orientation. It’s unclear why the artist chose to depict the plate as a non-mirror image — it certainly wasn’t because it made the map easier to paint. Maybe the artist was working from a copy of the map and not the original copper plate and didn’t know the image should be painted in reverse. Another possibility is that the artist wanted to make sure the map on the copper plate was recognizable as Blaeu’s work. Whatever the situation, he has provided several clues that help identify the map.

First, the words ‘Zuyder Zee’ are clearly visible on the plate. Second, in the decorative cartouche in the lower right corner, the letters ‘XVII PROVI’ can be seen. This identifies the map as a version of Blaeu’s Novus XVII, Inferioris Germaniæ Provinciarum Typus. This map was first issued in 1608 as a separately published map with decorative borders. Later, the borders were removed to publish it in Blaeu’s ‘Atlantis Appendix,’ which first appeared in 1630.

The Mariners’ Museum and Park, call# G1015.B63 Rare OO.

The Book: Exhibit #4 admitted into evidence

Sadly, despite countless hours of investigation, the book sitting on the left end of the table remains unidentified. When Blaeu wanted to create a new map, he did not go out and measure land masses or coastlines himself, he designed it using existing maps and books, ship’s logs, travel reports, and even conversations with sailors. The publication could be a small sea-atlas or pilot book — the frame around the map certainly gives the impression it’s a published work — but it could just as easily be an unpublished log book or manuscript.

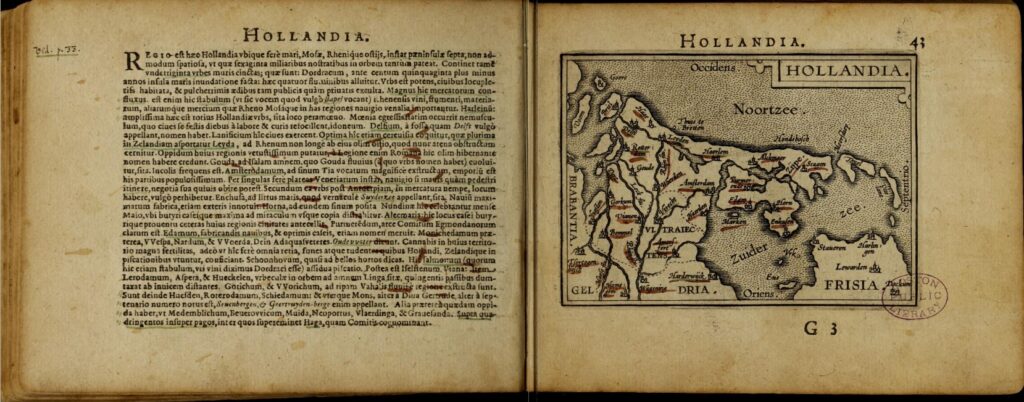

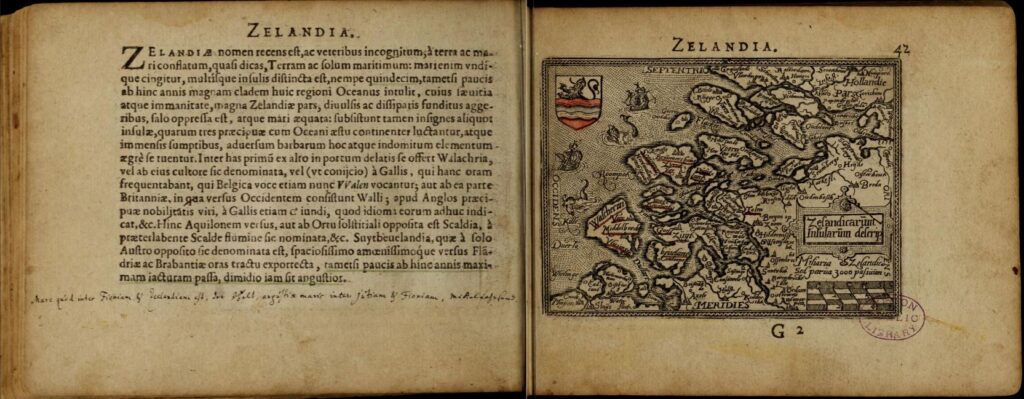

Since the engraving plate shows Blaeu’s map of the 17 provinces, reputedly in the process of being engraved, it’s probable the book’s map shows the detail of some part of the Netherlands coastline in the late 16th or first quarter of the 17th century. Things like this most certainly exist. For example, check out the maps of ‘Hollandia’ and ‘Zealandia’ in Abraham Ortelius’s pocket atlas Epitome Theatri Orteliani which was first produced in 1577.

An even closer match can be seen in the hook-shaped island of Zuid-Beveland in Zeeland on Abraham Ortelius’s map Zelandicarvm Insvlarvm from his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, granted this is a full-size map and we’re only looking at a small-scale detail map in the painted book. Unfortunately, I don’t hold out much hope that we’ll ever positively identify the book on the table.

The Mariners’ Museum and Park Call#G1015.O77 1592 Rare OO.

So, three out of the four objects sitting on the table depict Blaeu productions and the artist portrays the copper plate as if it is in the process of being engraved. This evidence strongly suggests that the suspects in our painting are Willem Blaeu and his sons Joan and Cornelis. It’s unclear who the woman is, but the lace collar and cap suggest she isn’t a servant despite the presence of an apron. As she’s standing behind Willem and is wearing a decorative gold wedding band, one could assume she is Willem’s wife Maritgen. The estimated date of the portrait is 1625 to 1630, which is around the time that Willem’s eldest son Joan joined his father’s business. While Cornelis is still young at this point, he must have had some interest in and knowledge of the family business, because he joined Joan in the running of the Blaeu publishing house after Willem died in 1638.

Prime Suspects Identified: Who are the Blaeus and why is the attribution so important?

Willem and Joan, and to a lesser extent Cornelis, operated one of the greatest cartographic publishing firms in history.

Willem Janszoon (the surname Blaeu or Blaeuw wasn’t added until 1621) was born in the Netherlands in 1571. His first career was as a clerk in his uncle’s herring packing business, but he quickly shifted to the study of mathematics and astronomy. In 1595 or 1596, Blaeu traveled to the island of Hven, then to Denmark, to study with and assist the celebrated Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. During his time at Uraniborg, Brahe’s world-renowned astronomical observatory, Blaeu learned the theory and practice of making astronomical observations and the arts of instrument and globe making.

manuscriptis observationum vicennalium, 1666. Episcopal Library at the Seminary of Barcelona.

When he returned to Alkmaar in late 1596 or early 1597, Blaeu opened a business as an instrument and globe maker. Sometime in 1597 or 1598, he married Maritgen Cornelisse van Uitgeest, and their first son, Joan, was born in late 1598 or early 1599. Shortly after Joan was born, Blaeu moved his business to Amsterdam, which was the home of a flourishing engraving and printing trade. Cornelis, the fifth of their seven children, is believed to have been born there in 1610.

Once in Amsterdam, Willem expanded his business to include engraving, printing, and publishing books, pilot and navigation guides, and maps. Along with his thriving business, Willem continued his astronomical investigations. He observed eclipses and performed astronomical observations in an effort to improve the accuracy of his maps and globes. Among other accomplishments, Blaeu discovered two new stars, took measurements to determine the earth’s circumference, and created a new printing press that quickly became standard equipment in Europe and England.

When the map and globe publishing business became more competitive in the late 1620s, Blaeu decided to publish a new atlas. He acquired 37 copperplates of maps produced by Jodocus Hondius the Younger (a Dutch cartographer who died in 1629), added 23 maps of his own, and published the Atlantis appendix, sive pars altera in 1630. Around this time, Joan, who held a doctorate from the University of Leiden, joined his father’s business. In 1631, Willem and Joan published a supplement to the Atlantis appendix with 100 maps called Appendix Theatri A. Ortelii et Atlantis G. Mercatoris. Over the next few years, foreign language editions of the two-part atlas were published, which gave the Blaeus a distinct advantage over their rival publishers.

On January 3, 1633, Willem became the official cartographer of the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie). In this position, he received all the journals, charts, and sketches compiled by the company’s pilots, sailors, and merchants. He used them to improve charts to and from southeast Asia and create sailing directions for the company’s navigators.

When Willem died on October 21, 1638, Joan, assisted by Cornelis, took over the family’s publishing business. Joan also inherited the position as the VOC’s cartographer. After Cornelis’s death in 1644, Joan continued the business alone and quickly established his own reputation as a great mapmaker. After completing Willem’s final atlas project in 1655, the Atlas novus, Joan began working on an even larger atlas to be called the Atlas maior. Published between 1662 and 1672, the Atlas maior is widely considered to be a masterpiece of the golden age of Dutch cartography. Besides the Atlas maior, Joan published a series of town books, which firmly established the eternal fame of the Blaeu name. On February 23, 1672, the Blaeu printing house in Gravenstraat burned down, destroying the business. A year later, Joan died. His sons attempted to carry what was left of the business, but it was never the same. In 1695, the business closed permanently and the inventory was sold at auction. Between the two of them, Willem and Joan had created the largest printing house in Europe, if not the largest printing business in the world.

While the attribution to Willem, Joan, and Cornelis Blaeu remains an educated guess based on the evidence provided by the artist, outside experts who have reviewed the research all firmly support the new attribution. So, for now, the prime suspects have been identified and Mariners’ considers this cold case closed.

[The curatorial scene investigator wishes to thank Lyles Forbes for all of the great suspect images and Willem Mörzer Bruyns for all of his great advice!]

Endnotes

1. The Museum was established by Archer and Anna Huntington and Homer Ferguson. Huntington owned the shipyard and Ferguson was its president. As a consequence, for many years shipyard employees coordinated all of the work of the Museum including the development and investigation of its growing collection.

2. Dirk Verwey was the Museum’s Rotterdam buyer.

3. D. Hannema, Director of the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen; M. Martin, Director of the Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis in the Hague; W. Voorceytel Cannenburg, Director of the Nederland Scheepvaartmuseum; and Dr. Ch. H. de Stuers at the Rijksprentenkabinet.

4. Possible suggested sitters over the years included Henry (or Hendrick) Hudson, Columbus, cartographer Gerard Mercator or cartographer Willebrord Snellius (aka Snel Van Royen), and cartographer Willem Blaeu. In 1991, another suggestion of Dutch navigator Willem Barents was suggested.

5. Over the years experts suggested the painting might be Dutch, England, Spanish, or Italian.6. The date on the globe is 1602, but the globe appears to be state 3 which was published in 1621. See page 501 and item 30 on page 505 of Globi Neerlandici by Peter van der Krogt.