Proximity

Proximity is an important and powerful, but often undervalued element in art. This can be something like the placement of two colors near one another, the arrangement of subjects in a work, or even the spacing of works from one another in a physical space. But this idea of proximity is important because it has the ability to impact or even completely change the way one or more works or elements are viewed. It’s a central concept of curation and exhibition design within gallery and museum spaces, too. The objects, placement, exhibition elements, and even the color of the walls all have the ability to influence the way that a viewer perceives the objects in front of them.

But my favorite benefit of proximity is the ability to add context and tell a greater story. Seeing one work alone may tell a part of that story, but when paired with another, and another, and another, it can feel like the pieces of a puzzle falling into place. Proximity, too, is one of the reasons I feel it is so impactful to be able to experience works of art in person. By being close to these objects, we then have the opportunity to form a relationship – become a part of the story, and they, a part of ours.

This collection of works by artist Milton J. Burns is an example of how proximity allows us to tell a greater story. It isn’t particularly an intentional series, as far as our records show, especially as the works were likely done across the span of 50 years between 1876 and 1925. But it’s one that, as I was searching through our catalog, felt natural – like these works belonged together whether the artist intended it or not.

A Portrait of a Fisherman

We begin with this portrait of a fisherman, our subject around whom this narrative revolves. We take in his characteristics – tanned skin and salt and pepper beard. He sits, relaxed as he looks off into the distance, squinting from beneath the wavy brim of his hat.

One strap of his beige apron falls casually off his shoulder. He’s dressed for a day on the water, just like the lifetime of days he’s already had. The work is on a small canvas, but in it, the artist has still shown us so much of this man’s personality. Through his demeanor and his appearance it is easy to believe that this man’s life revolves around the water, we can practically smell the salt that likely crusts his hat, skin, and clothing.

But he is without context. Anonymous. There are no ships, no water, no setting surrounding him. Through this work, we see but one facet. Just a portrait and it makes us wonder what his story is and sends us looking for more information.

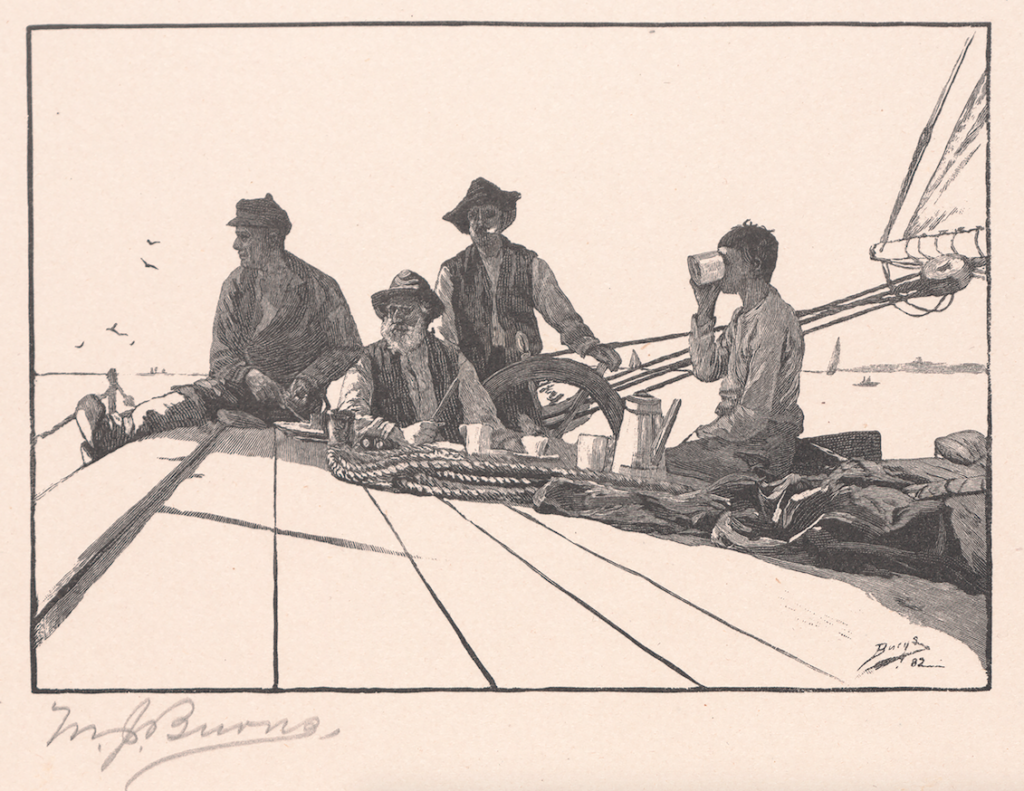

Fishermen in a Dory

As I continued searching, I was delighted to find works that brought context to the life of the fisherman including another scene with what could possibly be our same subject. In this scene, we see him actually out on the water in a small fishing dory. He peers off at a schooner obscured on a misty horizon as gentle rays of sun illuminate him in this scene. The artist’s placement of our subject on the water gives us context, we see a glimpse into his life and this time we see him, too, in proximity to another, younger mariner.

They row together through choppy swells which the artist has depicted with his quick, loose brushstrokes. While there is a lack of fear on the older fisherman’s face, his easy-going demeanor from the portrait is lost and we see concern marking the face of the younger mariner with him.

Through the artist’s composition, and his placement of the elements, the two fishermen in the small boat and the schooner far on the horizon, he’s weaving a narrative. This is a snapshot of life for this fisherman and for so many others, one that we could not have seen from his portrait alone.

Beached Boat Near Dock

The last two works don’t show the subject outright, but in grouping the four paintings, they work together to shape a larger narrative. After seeing the fishermen in the dory, this work of a boat beached near a dock stuck out to me. They’re not the same type of boat, but it seems like it could be one this fisherman used. It’s been left ashore at low tide, its sails lowered and resting in the bottom of the boat.

This work feels like it fits with the others, with this narrative of a fisherman, but simultaneously, without having the context of this boat’s location or the inclusion of our subject, it could be a boat on a beach anywhere. This work is one that I wondered whether to include in this grouping or not. On its own, we’d say that perhaps since it doesn’t match the boat in the previous work, then it doesn’t belong, but because of the power of proximity, it feels like it could be a part of the story. And that’s because of the final piece of the puzzle, the last piece in the arrangement – Twilight Fisherman’s Home – Scotland.

Twilight Fisherman’s Home – Scotland

This work, to me, is so inherently human without even having a person in the scene. It’s cozy and warm as the dusty colors of the sunset peek out from behind lavender clouds over the horizon. There’s a gentle glow from the last of the sun’s gentle rays. We see a lovely, quaint white cottage that sits just right of center. At the far left of the piece is a small, masted vessel and we wonder, could this possibly be the same boat from the previous work, Beached Boat Near Dock?

Its white hull gently reflects in the still water that laps at the shore. The scene is so serene, and there’s a loving warmth that the artist has brought to it. And this is where the power of proximity really stands out. Our view of the composition is such that we could be looking through the eyes of the fisherman, like he’s walking along the path up to his home after a day on the water. But the artist has also done something very clever, he’s placed the boat and the cottage close together, he’s even depicted them similarly: white boat, brown sails; white house, brown roof; so that we then understand that this fisherman’s home is not just his physical house, but the water too – this boat upon which he spends so much of his life.

Seeking Proximity

The concept of proximity is something that is also deeply ingrained in the story of the artist, Milton J. Burns whose entire life and artistic career was shaped by proximity to the water and to watermen like our subject. When he was just 16, he developed severe eye problems, the solution to this which – his doctor suggested – would be the sea air.

Burns sought proximity to the water through which he developed a closeness to watermen he met during his life as a working mariner and as a maritime artist.

This bond, formed through proximity, shaped the way he depicted his subjects and brings additional context and depth to the informal grouping we have here. We see mariners, vessels, landscapes, and experiences that Burns actually saw. His proximity to these vignettes of his own life ties the works together with an invisible thread that goes beyond their maritime themes.

The Universal Mariner

We know that these works were done in different locations: Scotland, Maine, and possibly elsewhere, and they spanned Burns’ career. But despite their differences, they still work together to add context to this narrative portrait of a fisherman. Many of them are unidentified and, therefore, lend themselves to this feeling of universality as if speaking not just to the identity of a Scottish fisherman or a mariner from Maine, but rather to a global identity of a mariner.

These universal commonalities that tie together mariners from many different times and locations are then embodied by our anonymous fisherman. Through this patchwork narrative, we get to see not just the face of a fisherman, or possibly his job, or his boat, or his house – but instead we see him.

The facets of his life. The places he calls home. By placing these works together and then ourselves with them, and with the artist too, whose experiences he’s shared through these works, we get the opportunity to get to know our fisherman, to see him deeper through these vignettes. To even see through his eyes. We see not just a painting of, but rather the portrait of – a fisherman.

About the Artist: Milton J. Burns

Milton James Burns was both an illustrator and painter, focusing primarily on marine subjects, including a large body of works depicting early America’s Cup Races. He was born in Mt. Gilead, Ohio on January 9, 1853. His introduction to maritime life came at the recommendation of his doctor at the age of 16 upon the diagnosis of a severe eye issue. His doctor suggested that the cure to young Burns’ ailment would be the sea air. So in July of 1869, Burns joined the crew of Panther, a Canadian whaling steamer. This initial journey was chartered by the maritime artist William Bradford for an expedition from St. John’s Newfoundland to the Arctic covering over 1,000 miles along Greenland’s coastline.

During his voyage with the artist, Burns discovered an interest in art and was able to study under Bradford. Following the expedition, Burns sought out an art education in New York, studying at the National Academy of Design and shortly after, became friends with Winslow Homer. The two spent a great deal of time together, traveling and sketching and both were drawn repeatedly to the coast of Maine. Several works in The Mariners’ collection feature sketches from Grand Manan and Monhegan Island. In looking at works by the two artists, some similarities can be seen in their compositions and it seems that Homer drew inspiration from Burns’ time at sea.

Milton J. Burns continued working at sea while continuing his art education. By the early 1870’s he became a freelance illustrator and throughout his career, his works could be found in Harper’s, Scribners, Literary Digest, and more. He married Mary Gertrude Ward and the couple lived in New Jersey for many years, though Burns continues to travel. They had 3 sons, Donald, Malcolm, and Robert.

Burns struggled financially at times, caught between painting and illustration which became more and more obsolete for publications during his career due to the rise in photography. During WWI, Burns was commissioned to document the US Navy’s operations against the German fleet. In 1932, while working in France, Milton J. Burns became ill and returned to the United States. He died on his houseboat on the Hudson River on December 27, 1933.

Watch the full episode!

Sources:

- https://aradergalleries.com/collections/milton-j-burns-1853-1933

- Milton J. Burns, Marine Artist, by Peter Hastings Falk

- https://research.mysticseaport.org/coll/coll186/

- https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/161003864/person/362103969723/facts