Note: This blog contains direct quotes with outdated language that some readers may find offensive.

Matthew Henson was the first African American to reach and stand on one of earth’s farthest reaches – the North Pole. He traveled with Robert Peary’s expeditions to venture into the desolate lands of the Arctic. In 1909, Henson, Peary, and four Indigenous natives stood at the top of the world for the first time in recorded history. Together, they faced numerous dangers, harsh landscapes, and sub-zero temperatures.

Henson understood the magnitude of the attempt to reach the North Pole, and that he represented all African American people should he be successful. In Henson’s 1912 autobiography, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1912), he tells us in his own words about his experiences and the challenges he overcame that led him to his monumental polar achievement. Within the book, he describes his “strongest doubts” and remembers his journey as one filled with “toil, fatigue, and exhaustion.” Nevertheless, his story is one of perseverance, grit, and determination.

I could write about it, but wouldn’t you rather have Matthew Henson share his story? Come along with me as we follow in his own words, his epic journey to the North Pole.

Traveling on an early 20th-century ship had its charm, but also its share of discomforts. Henson describes being aboard SS Roosevelt as they made their way north toward the Arctic…

From Etah to Cape Sheridan, which was to be our last point north in the ship, consumed twenty-one days of the hardest kind of work imaginable for a ship…The constant jolting, bumping, and jarring against the ice-packs, forwards and backwards, the sudden stops and starts and the frequent storms made work and comfort aboard ship all but impossible.

And there were some important rules that had to be followed:

There is a general rule that every member of the expedition, including the sailors, must take a bath at least once a week, and it is wonderful how contagious bathing is. Even the Esquimos [sic] (now referred to as Inuit) catch it, and frequently Charley has to interrupt the upward development of some ambitious native, who has suddenly perceived the need of ablutions, and has started to scrub himself in the water that is intended for cooking purposes.

Henson, like the rest of the crew, had his assigned duties. But what did he do to pass the time while traveling for months onboard Roosevelt?

On board ship there was quite an extensive library, especially on Arctic and Antarctic topics…In my own cabin I had Dickens’ “Bleak House,” Kipling’s “Barrack Room Ballads,” and the poems of Thomas Hood; also a copy of the Holy Bible, which had been given to me by a dear old lady in Brooklyn, N. Y. I also had Peary’s books, “Northward Over the Great Ice,” and his last work “Nearest the Pole.” During the long dreary midnights of the Arctic winter, I spent many a pleasant hour with my books.

Matthew Henson was quick to give credit where credit was due. He regularly applauded the tenacity and aptitude of the Esquimos. After all, they knew the land better than anyone, having lived there for thousands of years. But Henson also regularly praised and credited the expedition’s success to the North’s unlikely hero – the dog.

Next to the Esquimos, the dogs are the most interesting subjects in the Arctic regions, and I could tell lots of tales to prove their intelligence and sagacity. These animals, more wolf than dog, have associated themselves with the human beings of this country as have their kin in more congenial places of the earth…Without the Esquimo dog, the story of the North Pole would remain untold; human ingenuity has not yet devised any other means to overcome the obstacles of cold, storm, and ice that nature has placed in the way than those that were utilized on this expedition.

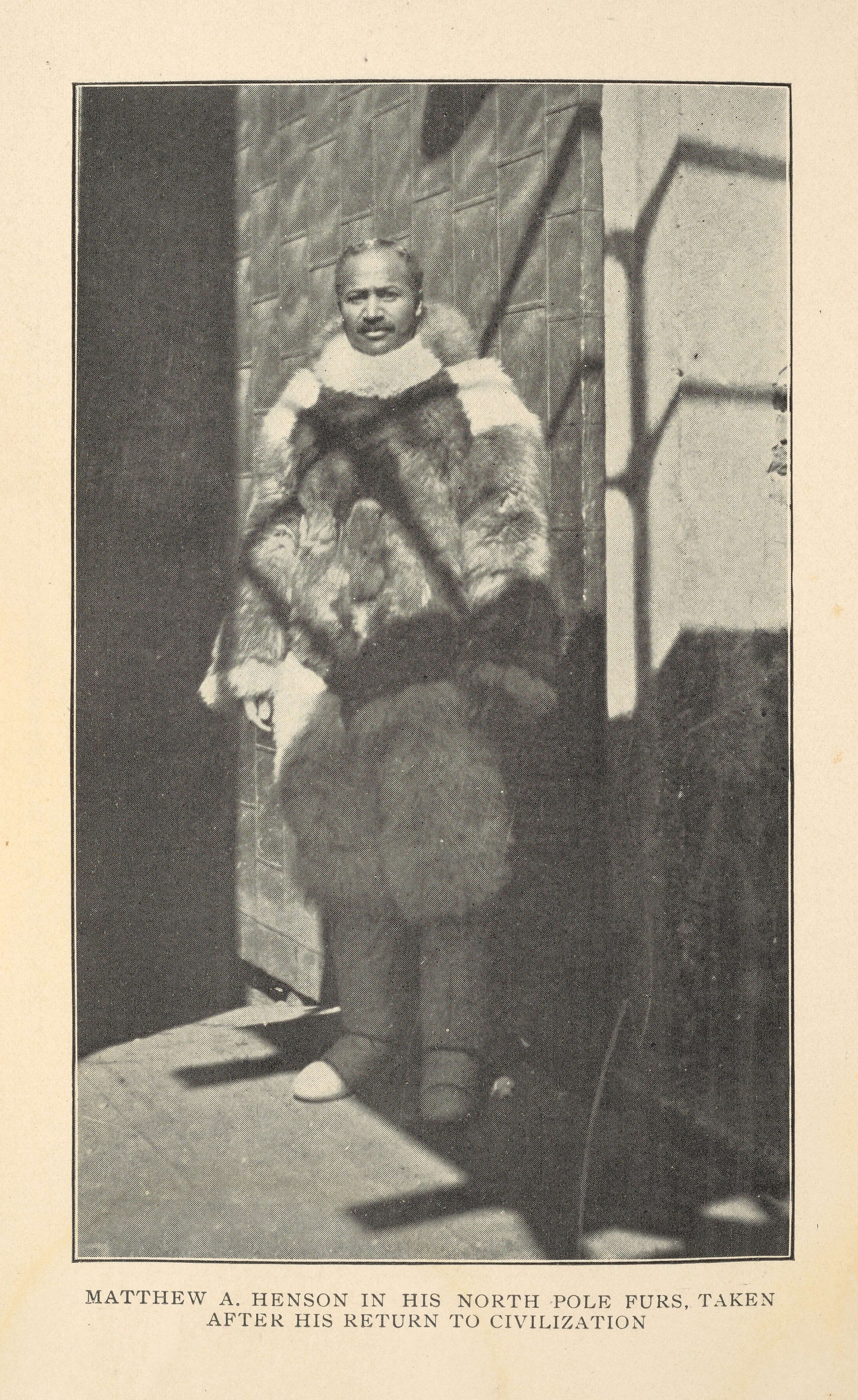

What does one pack to wear to the frigid Arctic tundra? Furs, of course. But fresh furs have to stay clean because if they get too dirty, they become infested with vermin.

It is easy to become vermin-infested, and when all forms of life but man and dog seem to have disappeared, the bedbug still remains. Each person had taken a good hot bath with plenty of soap and water before we left the ship, and we had given each other what we called a “prize-fighter’s hair-cut.” We ran the clippers from forehead back, all over the head, and we looked like a precious bunch…

The Arctic is no easy place to endure. Ice forms that shift under your feet. Blinding ice storms and dense fogs. Henson reminds us that traveling to earth’s farthest reaches was no simple feat:

These floes were hardly thick enough to hold a dog safely, but, there being no other way, we were obliged to cross on them. We set out with jaws squared by anxiety. A false step by any one would mean the end…For the next five hours our trail lay over heavy pressure ridges, in some places sixty feet high. We had to make a trail over the mountains of ice and then come back for the sledges. A difficult climb began. Pushing from our very toes, straining every muscle

It was during the march of the 3d of April that I endured an instant of hideous horror. We were crossing a lane of moving ice…when the block of ice I was using as a support slipped from underneath my feet, and before I knew it the sledge was out of my grasp, and I was floundering in the water of the lead. I did the best I could. I tore my hood from off my head and struggled frantically. My hands were gloved and I could not take hold of the ice, but before I could give the “Grand Hailing Sigh of Distress,” faithful old Ootah had grabbed me by the nape of the neck, the same as he would have grabbed a dog, and with one hand he pulled me out of the water, and with the other hurried the team across. He had saved my life.

The loss of life – especially that of his friend Professor Ross G. Marvin – weighed on Henson:

My good, kind friend was never again to see us, or talk with us. It is sad to write this. He went back to his death, drowned in the cold, black water of the Big Lead. In unmarked, unmarbled grave, he sleeps his last, long sleep.

As they neared their intended Polar destination, Matthew Henson begins describing the anxious excitement as they pressed onward:

Commander Peary and I were alone (save for the four Esquimos), the same as we had been so often in the past years, and as we looked at each other we realized our position and we knew without speaking that the time had come for us to demonstrate that we were the men who, it had been ordained, should unlock the door which held the mystery of the Arctic.

But the most evident feeling of pride came when they reached the North Pole on April 6, 1909:

A thrill of patriotism ran through me and I raised my voice to cheer the starry emblem of my native land. It was about ten or ten-thirty a. m., on the 7th of April, 1909, that the Commander gave the order to build a snow-shield to protect him from the flying drift of the surface-snow. I knew that he was about to take an observation, and while we worked I was nervously apprehensive, for I felt that the end of our journey had come….I was sure that he was satisfied, and I was confident that the journey had ended. Feeling that the time had come, I ungloved my right hand and went forward to congratulate him on the success of our eighteen years of effort…The Commander gave the word, “We will plant the stars and stripes—at the North Pole!” and it was done; on the peak of a huge paleocrystic floeberg the glorious banner was unfurled to the breeze, and as it snapped and crackled with the wind, I felt a savage joy and exultation.

Matthew Henson was aware that his contribution alongside Peary was a major accomplishment to all people of his race. His words demonstrate that he understood he would now have a place in history, alongside the great triumphs of other people of color:

Another world’s accomplishment was done and finished, and as in the past, from the beginning of history, wherever the world’s work was done by a white man, he had been accompanied by a colored man. From the building of the pyramids and the journey to the Cross, to the discovery of the new world and the discovery of the North Pole, the Negro had been the faithful and constant companion of the Caucasian, and I felt all that it was possible for me to feel, that it was I, a lowly member of my race, who had been chosen by fate to represent it, at this, almost the last of the world’s great work.

As Henson’s words reach the end of his book and his journey back home concluded, his final thoughts are of a bittersweet longing. There is pride in what he had done mixed with a yearning to be back in the Arctic lands, where friendships were made and historic feats completed:

To-day there is a more general knowledge of Commander Peary, his work and his success, and a vague understanding of the fact that Commander Peary’s sole companion from the realm of civilization, when he stood at the North Pole, was Matthew A. Henson, a Colored Man…

And now my story is ended; it is a tale that is told.

I long to see them all again! the brave, cheery companions of the trail of the North….the lure of the Arctic is tugging at my heart, to me the trail is calling!

To read more about Henson’s early life and work with Robert Peary, please read the blog post “Matthew Henson: An Arctic Explorer”, by Liz Williams, The Mariners’ registrar.

Explore More:

This video shares the incredible story in Henson’s own words from his 1912 autobiography “A Negro Explorer at the North Pole”. The journey to learn more about his significant feat all started when one of our curators, Erika Cosme, decided to read more about Henson’s impact on Black history…