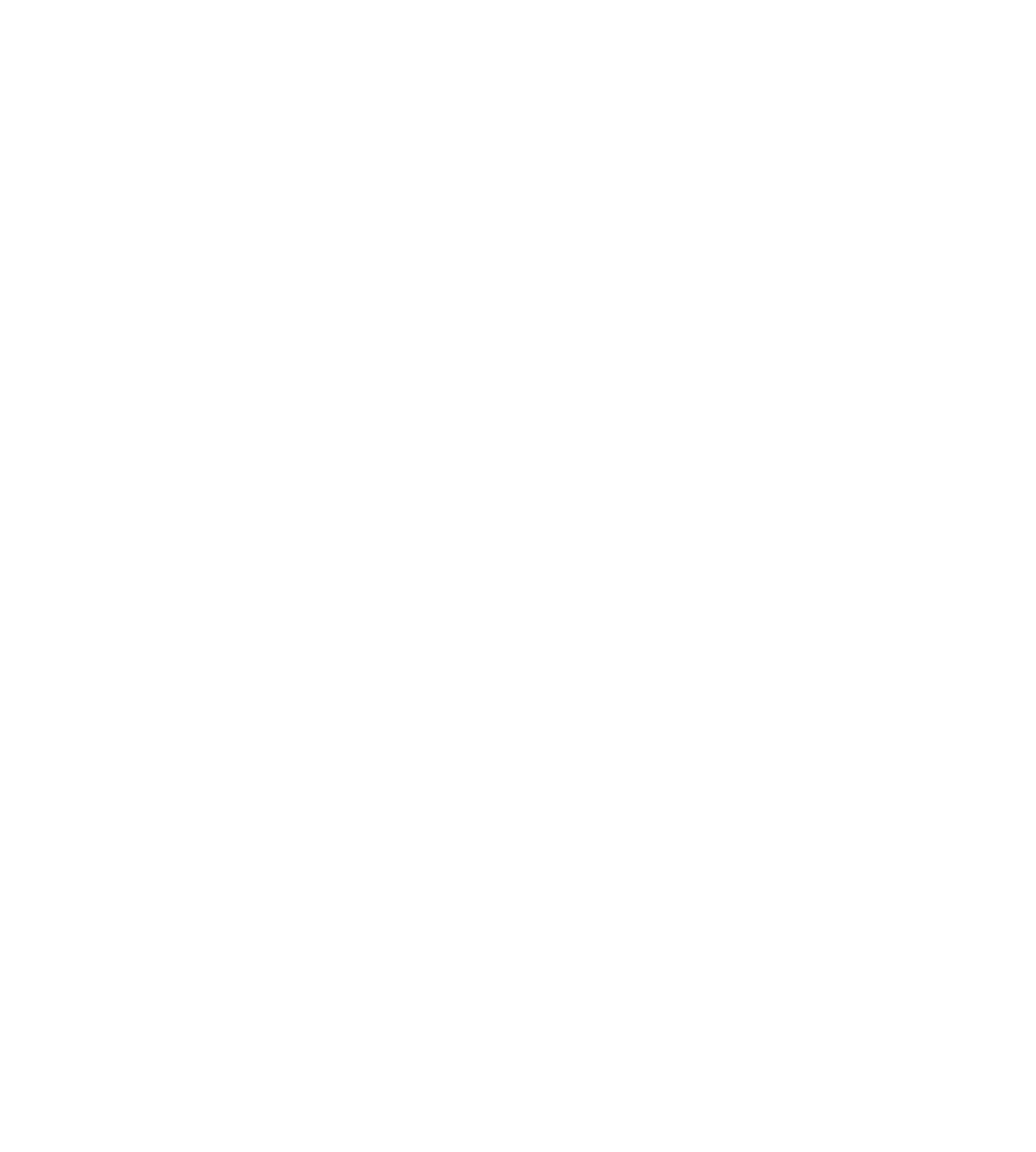

USS Somers was one of the most ill-fated warships in US naval history. Plagued by a mutinous crew which resulted in three executions, the ship ended its service when Somers tragically and quickly sank in a violent squall off Vera Cruz, Mexico. The brig’s infamous four-year career resulted in the creation of the US Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, as well as Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard built the brig launching it on April 16, 1842. The vessel Somers was commissioned on May 12, 1842, with Commander Alexander Slidell Mackenzie as captain. The warship was to act as an experimental scholarship for naval apprentices.

A Heroic Namesake

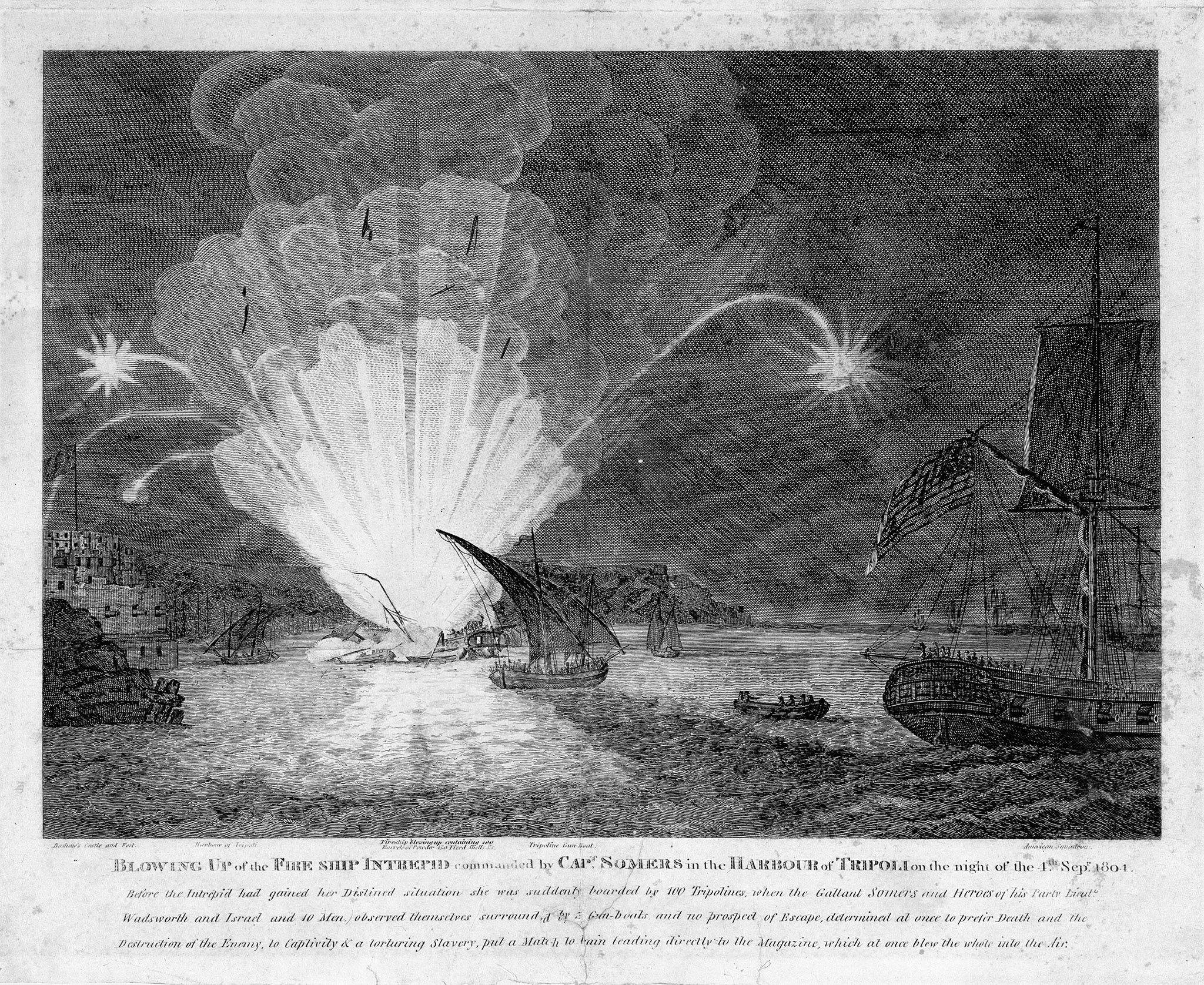

USS Somers was named in honor of Master Commandant Richard Somers, who was killed on September 4, 1804, during the First Barbary War. Somers was born in Egg Harbor, New Jersey, and attended Philadelphia’s Episcopal Academy with fellow future naval heroes Charles Stewart and Stephen Decatur. The three midshipmen’s first tour of duty was aboard USS United States during the Quasi-War with France. The warship was one of six frigates built under the Naval Act of 1794. Commanded by Captain John Barry, the frigate mounted 55 guns. Somers learned a great deal during the Quasi-War as United States captured several French privateers and sank the schooner, L’Amour de la Patrie.

After an induced leave, Somers was placed in command of the schooner USS Nautilus on May 5, 1803, and joined Commodore Edward Preble’s squadron off Tripoli during the First Barbary War. Somers then assumed command of the fireship USS Intrepid. Called a ‘floating volcano,’ the ship was crewed by 13 volunteers. Intrepid came under fire when entering the harbor from some carronades in a shore battery. The fireship blew up prematurely, killing Somers and his entire crew. It is generally believed that Somers exploded his ship to prevent its capture; he is considered one of the US Navy’s first martyrs.

USS Somers Characteristics

LAUNCHED: April 16, 1842

COMMISSIONED: May 12, 1842

DISPLACEMENT: 263 tons

LENGTH: 100 ft.

BEAM: 25 ft.

DRAFT: 14 ft.

PROPULSION: sail

COMPLEMENT: 13 officers and 80-120 men

ARMAMENT: 10 x 32-pounder carronades

FATE: Sank in storm December 8, 1846

THE Literary Luminary Commander

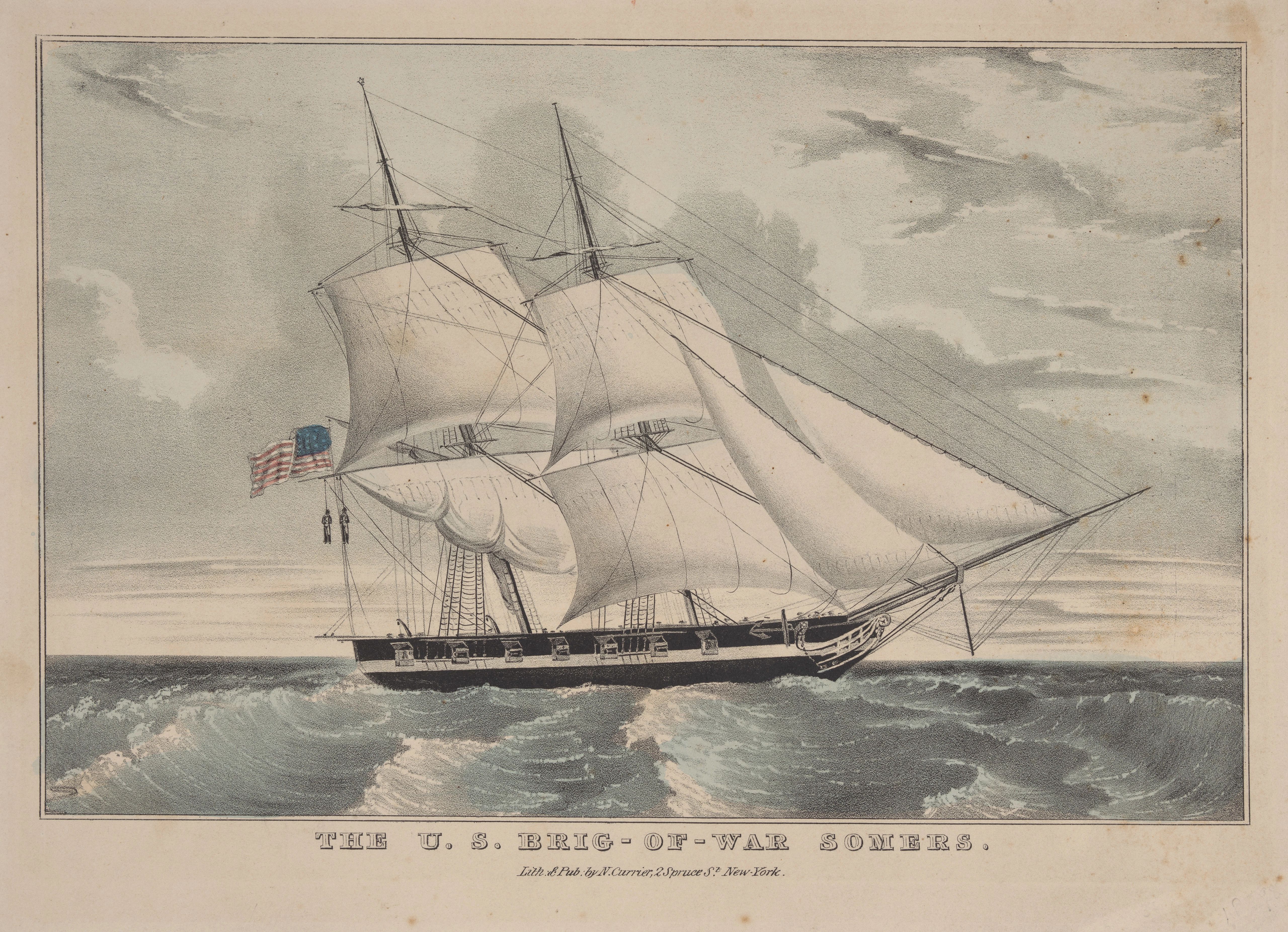

Somers commander, Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, came from a politically powerful Louisiana family. His older brothers included Thomas Slidell, chief justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court, and John Slidell, US Senator from Louisiana. His eldest sister married Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry, which gave young Alexander Slidell access to Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry and Stephen Decatur’s papers. Alexander’s younger sister married the son of Commodore John Rodgers, C. R. P. Rodgers. In 1838, Alexander formally changed his last name to Mackenzie, a condition issued to receive a large inheritance from his maternal uncle.

Alexander Slidell Mackenzie was a prolific author publishing the likes of Oliver Hazard Perry: Famous American Naval Hero, Victor of the Battle of Lake Erie, His Life and Achievements (1840), and Life of Stephen Decatur: A Commodore in the Navy of the United States (1846). A personal friend of such notable authors as Washington Irving, Richard Henry Dana, Jr., and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Mackenzie had served in the US Navy since 1815 and appeared to be the perfect officer to command a schoolship.

Off to Africa

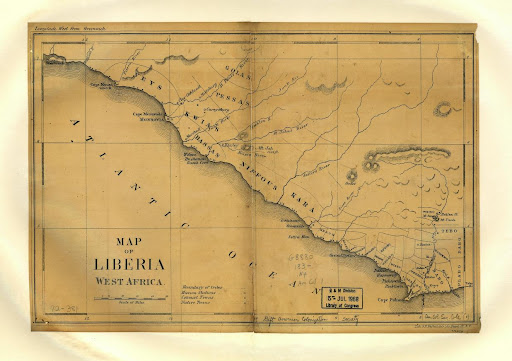

Somers went on a shakedown cruise from New York to Puerto Rico and back from June to July 1842. On September 13, USS Somers shaped a course for the Atlantic coast of Africa with dispatches for USS Vandalia on anti-slave patrol. Mackenzie missed Vandalia at ports like Madeira, Portugal, Tenerife, Spain, and Porto Praia, Cape Verde Islands, until he arrived at Monrovia, Liberia. It was there that Somers’ commander learned that the frigate had already sailed back to America. He hoped to catch up with Vandalia at St. Thomas, Virgin Islands.

Enter Philip Spencer

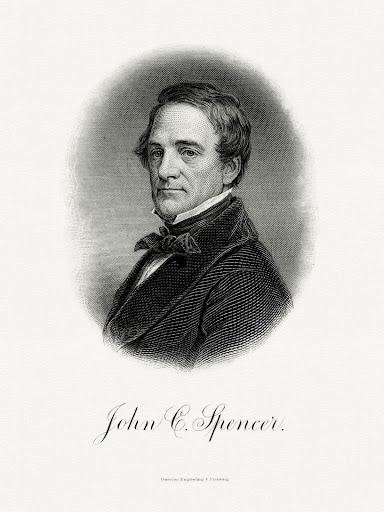

Mackenzie and other officers noted that the crew’s morale had declined: the crew was generally sullen, discontented, and inattentive to duty. It appeared that a minor incident could evoke major troubles. Onto this stage stepped an unruly and intemperate midshipman, Philip Spencer, the son of Secretary of War John C. Spencer, who served in President John Tyler’s cabinet.

Philip Spencer initially attended Geneva College, where he was considered highly intelligent; however, he was also seen as wild and beyond control. He then attended Union College, where he became a founder of the Chi Psi Fraternity. He did not last long as a college student and left school, signing onto a Nantucket whaler. The young Spencer had always enjoyed reading sea stories, especially pirate tales. Secretary Spencer interceded and told his son that if life at sea was what he really wanted, then Philip should live it as a ‘gentleman,’ meaning as a commissioned officer.

Spencer’s father obtained a midshipman’s commission for his son. Joining the US Navy did nothing to stabilize or discipline the young sailor. While drinking, he twice assaulted a senior officer aboard USS North Carolina. Reassigned to USS John Adams, he was involved in a drunken brawl with a Royal Navy officer in Rio de Janeiro. He resigned his commission to avoid a court-martial, yet, it was not accepted due to his father’s position. Accordingly, he was detailed to the schoolship, Somers.

Oh, To Be a Pirate!

During the return voyage, Spencer gained favor amongst many of the crew, most of whom were young apprentices, highly influenced by his ability to provide them with rum and tobacco. Spencer told the purser’s steward, J.W. Wales, on 25 August 1842 of his plot to mobilize about 20 crew members in a mutiny. He planned to kill most of the officers and other non-conformists. Once in complete control, Spencer intended to use Somers as a pirate ship in the West Indies. Seaman Elisha Smalls was deeply involved in the planning. Seaman Elisha Smalls, also present at the secret meeting, told Wales he would be killed “if he revealed the plan to anyone.”

Mutiny Uncovered

The next day, on November 26, Wales told purser H.M. Heiskill and First Lieutenant Guert Gansevoort about Spencer’s plot. In turn, Gansevoort advised Mackenzie of the situation. At first, Captain Mackenzie did not consider the plot serious and thought it might just be an exaggeration. Nevertheless, he instructed Gansevoort to watch Spencer and other ratings for any signs of revolt. The lieutenant did glean from several loyal crew members that Spencer had nightly meetings with Smalls and Boatswain’s Mate Samuel Cromwell. Both of these men crewed slave ships before joining the US Navy. Cromwell was noted for his lack of character and deep, disparate hostility to the command structure. Later that day, Spencer was observed looking diligently at charts of the West Indies, asking questions about the Isle of Palms — a notorious haunt for Caribbean pirates – and seeking more knowledge about an essential tool for celestial navigation, a chronometer. Observers noted how much joy Spencer was having sketching a sailing ship flying the black flag of piracy. Evidence against Spencer’s mutinous thoughts made it clear that the young and foolish midshipmen were up to no good.

Mackenzie confronted Spencer with his suspicions and Wales’s tale. Spencer replied that he told the pirate plan to Wales as a joke. Mackenzie was not amused. The midshipman was arrested and placed in double irons on the quarterdeck. When Spencer’s locker was searched, two papers written in Greek were discovered. Midshipman Henry Rodgers translated them. The documents, known as the Greek Papers, proved Spencer was planning a mutiny. The papers listed the plotters’ names, possible supporters, and those considered unlikely to join the uprising. A horrific passage in Spencer’s notes stated the “remainder of the doubtful will probably join when the thing is done, if not, they must be forced. If any not marked down wish to join after the thing is done we will pick out the best and dispose of the rest.”

More Troubles

The Greek Papers proved that Spencer was indeed concocting a mutiny. A tense mood seized Somers. Concerns elevated when the crew was aloft in the masts hoisting the sails when a mast failed, damaging the rigging on November 27. Events such as this made everything seem very suspicious. Boatswain’s Mate Samuel Cromwell, known as the largest man in the crew, was believed to have caused the accident as a diversion to free Spencer. It was known that Cromwell had previously met with Spencer. Cromwell was confronted by Gansevoort and questioned about his meetings with Spencer. Cromwell replied, “It was not me, sir – it was Small.” Small was immediately interrogated, admitting he had met with Midshipman Spencer. Both men quickly joined the disgraced Midshipman Spencer in double irons on the deck.

Later that evening, fears of sabotage were heightened when several crewmembers rushed onto the quarterdeck just as a new topgallant was being hoisted. Gansevoort suspected it was an attempt to free the prisoners. He quickly pulled out his Colt revolver, pointing it at Sailmaker’s Mate Charles A. Wilson, This quelled the mob, and Midshipman Rodgers took the men aft.

The Plot Thickens

On November 28, wardroom steward Henry Waltham was flogged with 12 strokes of a cat o’ nine tails for stealing brandy for Spencer. After Waltham’s punishment, Capt. Mackenzie announced Spencer’s plot to seize the ship and murder loyal crew members. Waltham had not learned his lesson from his previous lashes. The wardroom steward tried to convince one of the apprentices to steal three bottles of wine for the prisoners, resulting in Waltham flogged again on November 29.

That day, more discord was observed as Sailmaker’s Mate Charles A. Wilson and Apprentice Alexander McKee (McKie) were caught trying to access the weapons’ locker. Two others, Landsman McKinley and Apprentice Green, missed muster, failing to show up for their midnight watch.

Facing The Crisis

Morning dawned on November 30, 1842. Tension aboard Somers heightened to a pitch. Mackenzie knew he had to take action. Accordingly, four more men – Wilson, McKinley, Green, and McKee – were placed in irons, bringing seven men arrested, accounting for 6 percent of the crew. Mackenzie realized there might be more siding with Spencer. Somers’ commander knew he did not have the resources to secure the prisoners and felt a growing concern for the brig’s safety.

Mackenzie addressed a letter later that day to seven officers – Lt. Gansevoort, Passed Assistant Surgeon L. W. Leecock, Purser Heisill, Acting Master M.C. Perry, and Midshipmen Henry Rodgers, Egbert Thompson, and Charles Hayes – requesting their opinions on how best to resolve this dangerous situation. Meeting in the wardroom, they interviewed various crew members and gathered other evidence.

Prove and Punish the Villains

The next day, December 1, the officers reported they had “come to a cool, decided, and unanimous decision,” stating that Spencer, Small, and Cromwell were “guilty of a full and determined intention to commit mutiny on board of this vessel of a most atrocious nature.”

The panel believed that others on the ship were in league with Spencer. The officers recommended that the three mutineers be “put to death in a manner best calculated as an example to make a beneficial impression on the disaffected.” They gave their judgment “ in mind of our duty to God, our country, and to the service immediately executed and buried at sea.

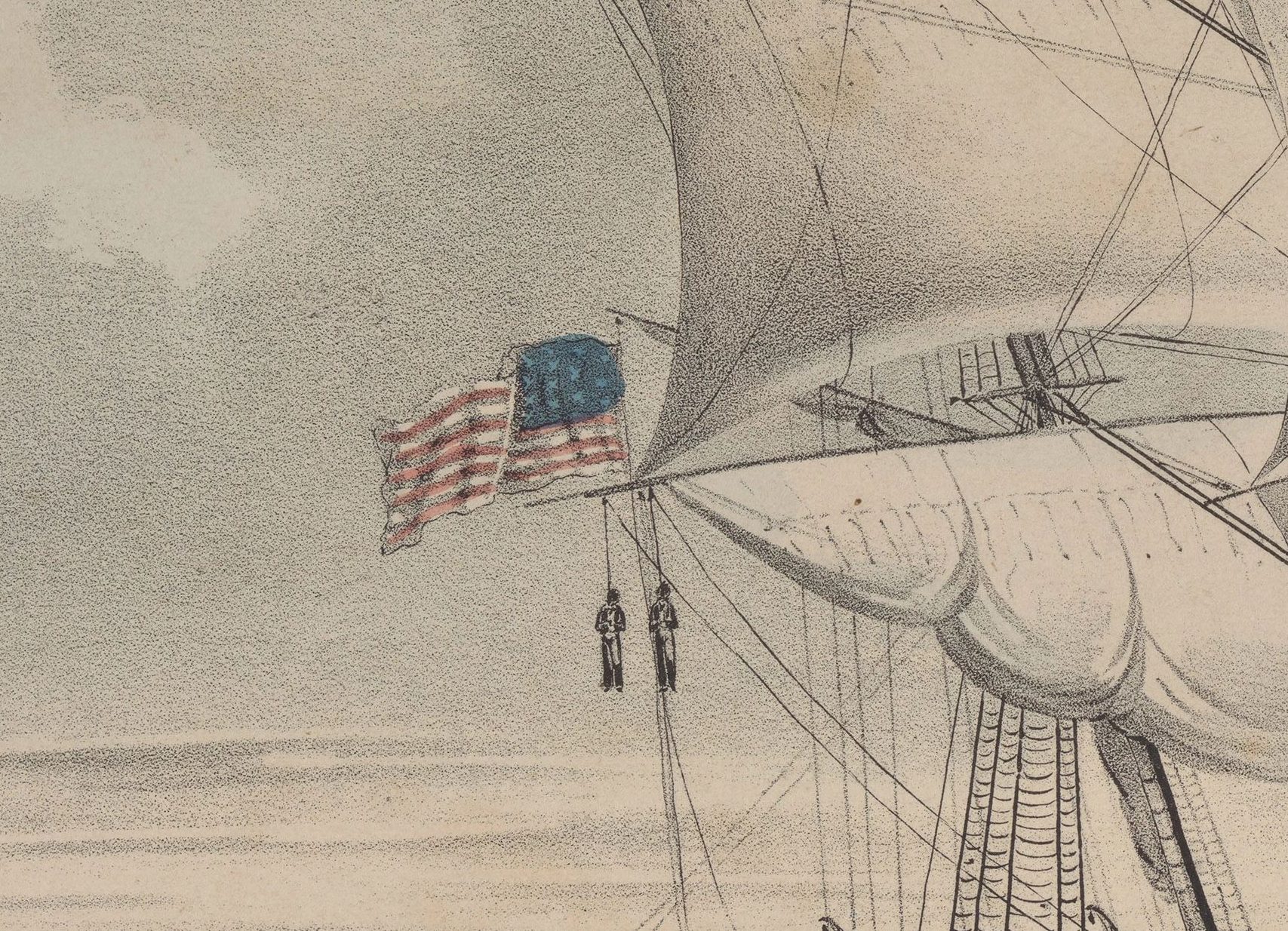

Mackenzie decided to execute the prisoners that afternoon. At 1:45 p.m., the crew was assembled on deck, and the condemned men were brought forward. “The charges were read and defendants were secured to ropes hoisted over the ship’s yardarm. At 2:15 p.m., the condemned were hoisted aloft underneath the ship’s ensign (United States flag).” All hands were ordered to give three cheers as a salute to the flag and three cheers for the ship.” The bodies were taken down at 3:30 p.m., and the condemned dead mutineers were buried at sea.

The Mariners’ Museum and Park # 1935.0696.000001.

Return Home to Controversy

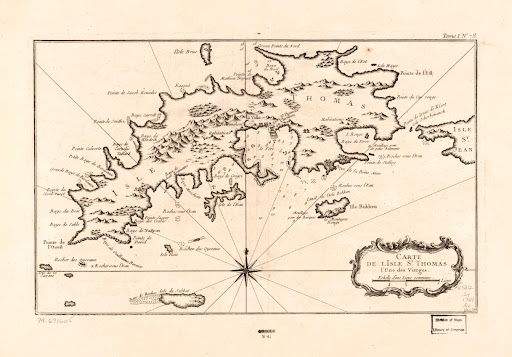

USS Somers reached St. Thomas on December 5 and New York City on December 15, 1842. A total of twelve suspected mutineers were placed on USS North Carolina and were later moved into confinement in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

When news of Spencer’s death spread throughout the nation, the US Navy convened a court of inquiry to investigate the mutiny and its outcomes. The proceedings exonerated Mackenzie. Nevertheless, he asked for a court-martial to completely clear his name from the shadow of Philip Spencer’s death. Secretary of War Spencer would likely have demanded a court-martial anyway. In addition to losing his son, Spencer wanted to investigate America’s first naval mutiny. The trial lasted from January 28 to March 31, 1843.

Three criminal charges of murder were levied against Mackenzie for the death of three seamen suspected of mutiny. He was also charged with two counts of oppression, illegal punishment, and conduct unbecoming a naval officer. Mackenzie’s defense was, “When we made more prisoners from the crew than we had the force to take care of, and I was more fully convinced of the necessity to execute Mr. Spencer, Cromwell, and Small for the safety of the crew.” Mackenzie, who defended himself in these proceedings, closed his defense with, “I admit that Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer, Boatswain’s Mate Samuel Cromwell, and Seaman Elisha Small were put to death by my order, but, as under existing circumstances, this act was demanded by duty and justified by necessity, I plead not guilty to the charges.’’ The witnesses supported Commander Mackenzie’s accounting of the events associated with the mutiny and subsequent executions.

Results

Mackenzie was innocent of all charges by the court. The court stated, “All these charges involved the life of the accused, and as the finding is in his favor, he is entitled to the benefit of it, as in the analogous case of a verdict before a civil court; and there is no power which can constitutionally deprive him of that benefit. The finding, therefore, is simply confirmed and carried into effect, without any expression of approbation.” This judgment and statement were meant to protect Mackenzie from any civil suit that Secretary Spencer (known as being a vindictive man) or others might bring against Somers’ commander.

The Court Of Public Opinion

Public opinion remained against Mackenzie to the extent that James Fenimore Cooper published a book, Proceedings of the Naval Court Martial in the Case of Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, a commander in the navy of the United States, & c: Including the charges and specification of charges preferred against him by the Secretary of the Navy. Cooper annexed a final review which cast doubt on the court’s findings. He considered the lack of a formal court-martial aboard Somers controversial and questioned Mackenzie’s conduct. This volume continued the Cooper-Mackenzie feud, which began over the September 10, 1813, Battle of Lake Erie. The authors had contrasting opinions about Lieutenant Jesse Elliott’s role during the battle. Cooper considered Mackenzie’s court-martial biased and made a case against Somers’ commander. The feud ended with Mackenzie’s death in 1848.

Lessons Learned

The Somers Mutiny had a significant impact on US naval officer training. The need for midshipman education was evident as the USS Somers cruise was to use the brig as a schoolship. The mutiny made it clear to Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft that a better solution was needed. Bancroft secured appropriations for establishing the US Naval Academy in 1845; Captain Franklin Buchanan was the first superintendent.

Flogging No More

Flogging has been a standard discipline practice in the US Navy since the 1790s. It was a standard method of punishment without court-martial, and each infraction by seamen warranted a certain number of lashes. Many officers, such as Commodore Thomas Truxtun in 1800, believed flogging extremely cruel and should be abolished. The Somers Mutiny brought this painful practice to the forefront. James Fenimore Cooper’s vendetta against Commander Mackenzie included many anti-flogging comments. Cooper reviewed Somers’ log book, believing there was excess use of flogging on board the brig during Somers’ last voyage. Mackenzie needed to enforce punishments due to his somewhat surly crew. Each flogging in the log detailed why this harsh punishment was rendered. “It cannot be denied,” Cooper wrote, “that some of the powers delegated to naval officers are looked upon with disfavor by many reflecting men. The law permits it, it is true, on the grounds of necessity….” American public opinion following the Somers Mutiny helped the US Congress end flogging in 1850.

Billy Budd, Billy Budd

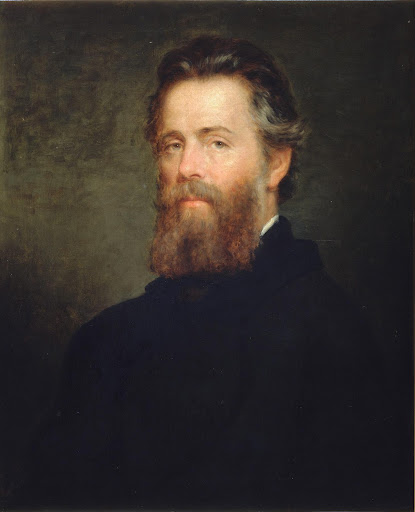

One of Herman Melville’s greatest stories is the sad tale of Seaman Billy Budd. Melville wrote an unfinished novella that was completed and published long after his death. Melville gained detailed insights about the Somers Mutiny from his first cousin, Guert Gansevoort, who was the first lieutenant aboard the brig. Melville incorporated themes and elements of the Somers Mutiny in Billy Budd.

New Duties

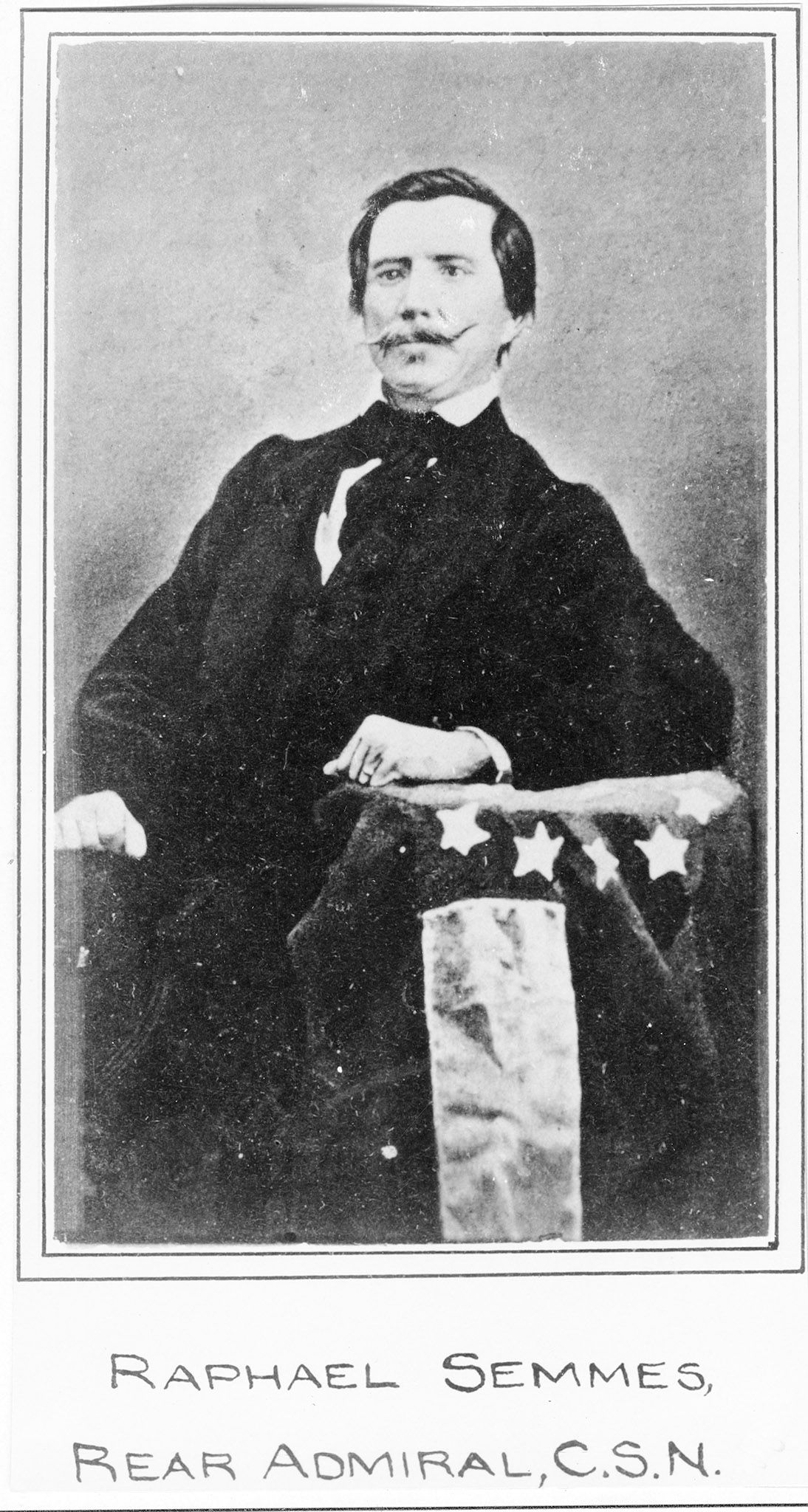

After the legal proceedings were finished, Lieutenant John West took command of Somers, and the warship was assigned to the Home Squadron. Somers served along the East Coast and West Indies. When the Mexican War erupted, the brig was in the Gulf of Mexico under the command of Lt. Duncan Ingraham. Ingraham became very ill and was replaced by Lieutenant Commanding Raphael Semmes.

The Blockader

Semmes was pleased with the brig as it was fast; therefore, a very efficient blockader. Semmes found a safe anchorage for his ship off Isla Verde near the entrance to the Vera Cruz harbor. He was concerned about the ship’s safety as it only carried six tons of ballast to balance it. Semmes was determined to be a success and sent a boat party to capture the blockade runner Criolla. The schooner was captured and burned on November 26, 1846. The boat party brought away seven prisoners. Semmes soon learned that he had just destroyed Commodore David Conner’s spyship, which had been sent to Vera Cruz to investigate the port’s defenses.

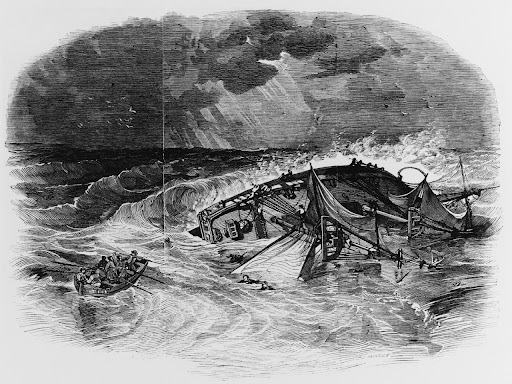

A Sudden Squall

On December 8, 1846, Semmes was chasing a blockade runner when a storm struck Somers. The brig quickly capsized as the gale increased; the vessel sank in 10 minutes. Semmes was able to get one boat away and ordered the rest of the crew: “Everyman save himself who can!” Somers’ commander was thrown into the sea and managed to hold on to one of the arm-chests’ gratings until rescued by the ship’s boat. He lauded his men for “the generosity with which they behaved toward each other in the water, where the struggle was one of life and death.” British, French, and Spanish warships, including HMS Endymion, rescued many survivors. Yet, 36 out of a crew of 80 men were lost during the sinking. Thus ended the tragic career of USS Somers.

For another interesting story about USS Somers, check out this blog from our Conservation team when they discovered that a painting of USS Somers was hidden by another ship….

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cooper, James Fenimore. The Cruise of the ‘Somers’ Illustrative of the Despotism of the Quarter Deck, and of the Unmanly Conduct of Commander MacKenzie: To which is Attached Three Letters on the Subject by the Hon. William Sturgis. New York: Library of America, 1985.

Defense of Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, Commander of the US Brig Somers, Before the Court Martial Held at the Navy Yard, Brooklyn, New York: Tribune Office, 1843.

McFarland, Philip. Sea Dangers: The Affair of the Somers, New York: Schocken Books, 1985.

Melton, Buckner. A Hanging Offense: The Strange Affair of the Warship Somers, New York: Free Press, 2003.

Melville, Herman, Billy Budd, Charlottesville: Freeman Press, 1948’

Semmes, Raphael. Service Afloat and Ashore during the Mexican War. Cincinnati: W. H. Moore & Co., 1851.

Vincent, Howard P. Twentieth Century Interpretations of Billy Budd, New York: Prentice-Hall, 1971.