What’s an Oil Reservoir?

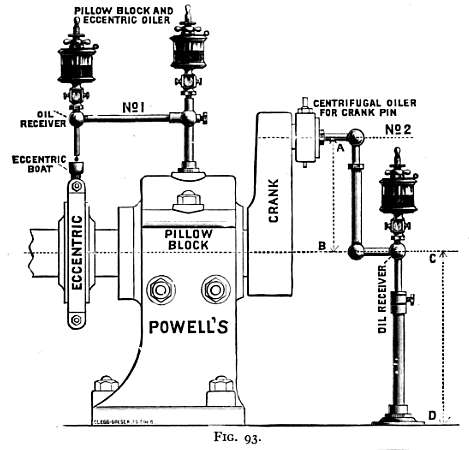

Oil reservoirs are a tool commonly found on USS Monitor‘s engine. Also known as an oil cup or lubricating cup, they were used on steam engines to keep valves and levers constantly lubricated. The diagram below shows how they directly screwed into valve joins.

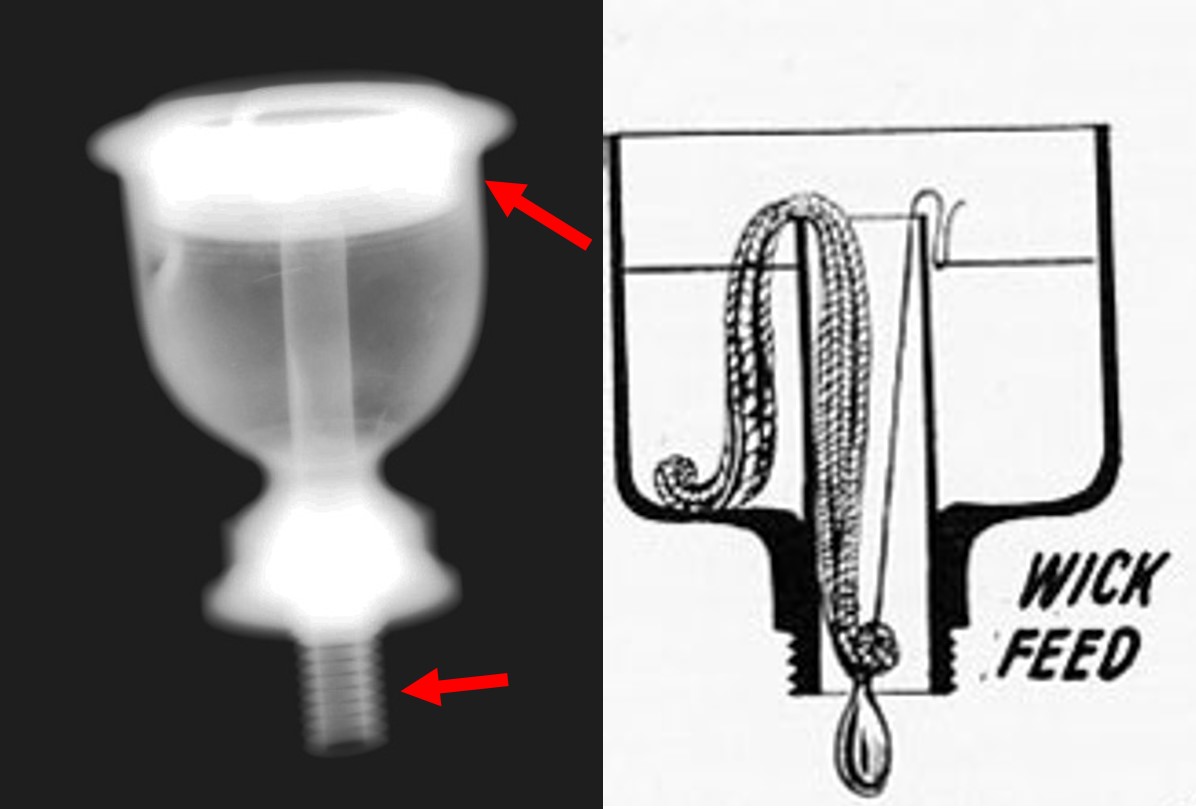

While there were many ways to oil engine parts, the kind we have found on Monitor are the “wick feed” variety (top left corner). The oil soaks the wick and slowly but continuously drips oil into the valve joins.

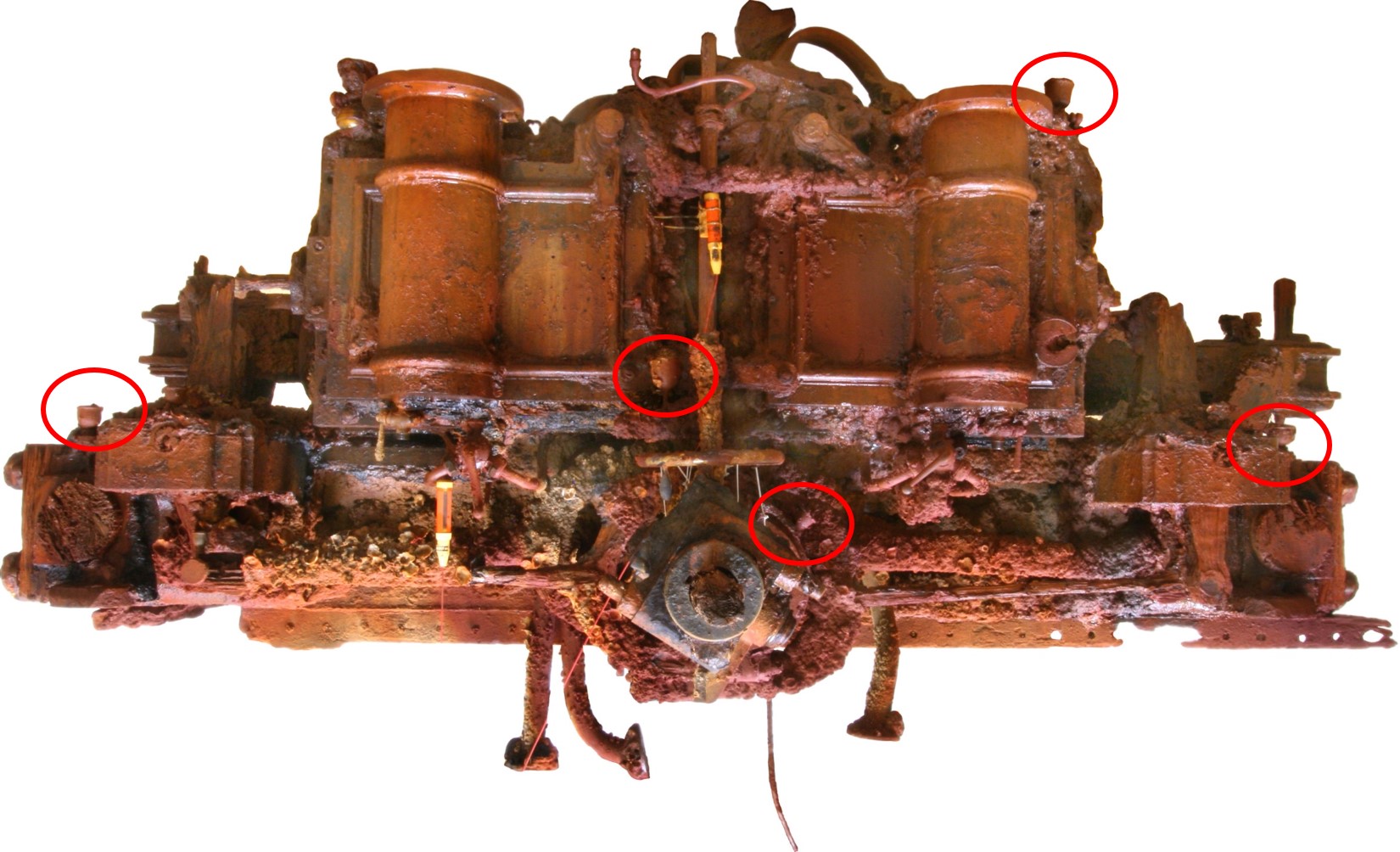

The steam engine of USS Monitor included complicated machinery and several new technologies. And with that, came a number of oil reservoirs. You can see just a few of them circled in red below.

What can an X-ray tell us?

As mentioned before, the oil reservoir would screw directly into a valve connection, as seen in this detail of the engine. After the oil reservoir was removed, we used X-Radiation to examine the interior. The x-ray was able to detail, not only the screw threads that attach the oil cup to the valve, but also showed that the oil cup cap is screwed on. The x-ray also confirms that this design is that of a “wick feed” oil reservoir.

How do we conserve the oil reservoirs?

The oil reservoirs are made from a copper alloy, and when they were removed from Monitor‘s engine, they were covered with corrosion and marine growth. They were also full of salts after spending over 100 years on the ocean floor. All of Monitor’s objects, including the oil reservoirs, must have these salts removed in order to prevent corrosion and be properly preserved.

We used two methods to achieve that goal. One was the mechanical removal of the corrosion and marine growth using picks and pneumatic tools. The second was a soaking process called desalination to remove the salts.

What does a chelator do?

Now that the oil reservoirs have been desalinated and the marine growth removed, it’s time for fine details. The majority of the corrosion was removed during mechanical cleaning, but as you can see in the images below, there is still a thin layer of dark corrosion on the surface. We want to remove as much of this corrosion as possible, to better preserve the oil cups.

We use chelators to remove this corrosion. Chelators are binding agents that latch on to corrosion so that when we rinse the surface with water, both the chelator and corrosion are rinsed away. Here we apply the chelator to the surface of the oil reservoir using a poultice, and let the chelators do their work!

After few minutes, we can then use cotton swabs and water to remove the chelator poultice. You can see the dark corrosion that has been removed on the cotton swab. Chelators allow for gentle removal of corrosion without damaging the object’s surface.

We’ll continue using chelators to remove corrosion from the oil reservoirs until the majority of corrosion is removed. It would be impossible to remove all the corrosion, and even if we could, making the objects look ‘like new’ erases their history from the shipwreck.

Treatment complete!

Once the oil reservoirs are stable, we will give them a protective coating to prevent future corrosion and they will go into storage or on display. This same method of conservation is used for many of the copper alloy objects from USS Monitor.