Let your eyes soften, and take a deep breath. Picture a happy memory or a moment. In this second of subconscious awareness, what do you see? Is it crisp and vivid, or soft and a little blurry? What do you feel? Happy or wishful, possibly something more visceral? An excited flutter in your chest or a slight prickle of the hairs on the back of your neck? What is it about this moment that left a lasting impression on you?

Think. Feel.

Breathe in. Breathe out.

Open your eyes.

A Familiar Unfamiliarity

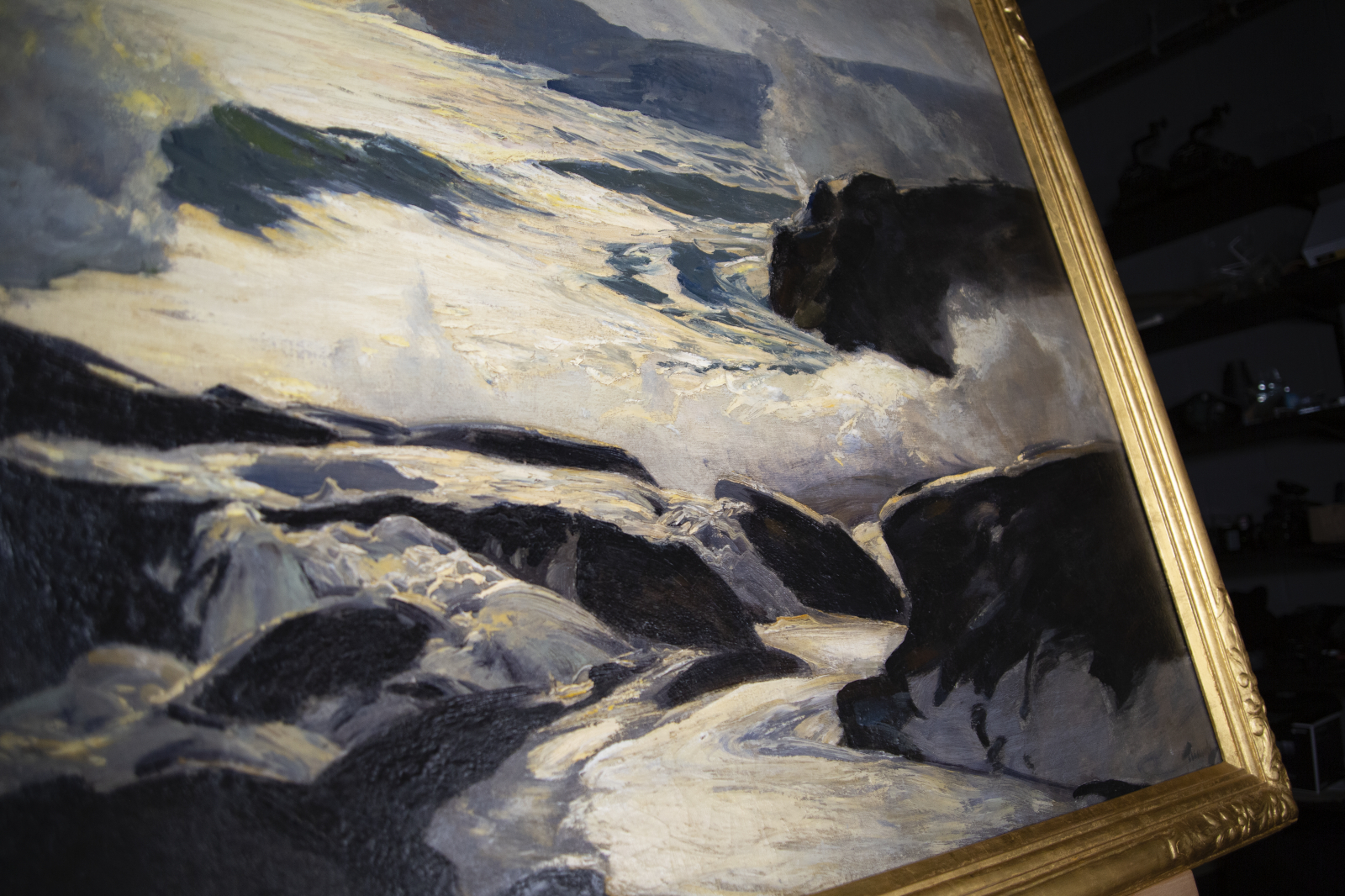

Have you ever had a moment that feels almost like Deja-vu? It feels like it’s a memory, but you know it isn’t? Experiencing “Full Tide” by Frederick Judd Waugh is a moment like this – a memory or possibly something deeper in our subconscious.

The glow of the sun on the water is hypnotizing, the luminescence forms a path that leads our eyes in – through the fore and middle grounds of the work, into the background, searching for the source of this ephemeral light. All the while the full tide splashes against the craggy coastline. The flowing water on the rocks creates an ever changing scene – no two moments the same. This simultaneously feels so unfamiliar and yet perfectly recognizable, as if this is our own memory that Waugh painted nearly 100 years ago. So how can it feel so familiar, so much like a memory of our own?

A Change in Perspective

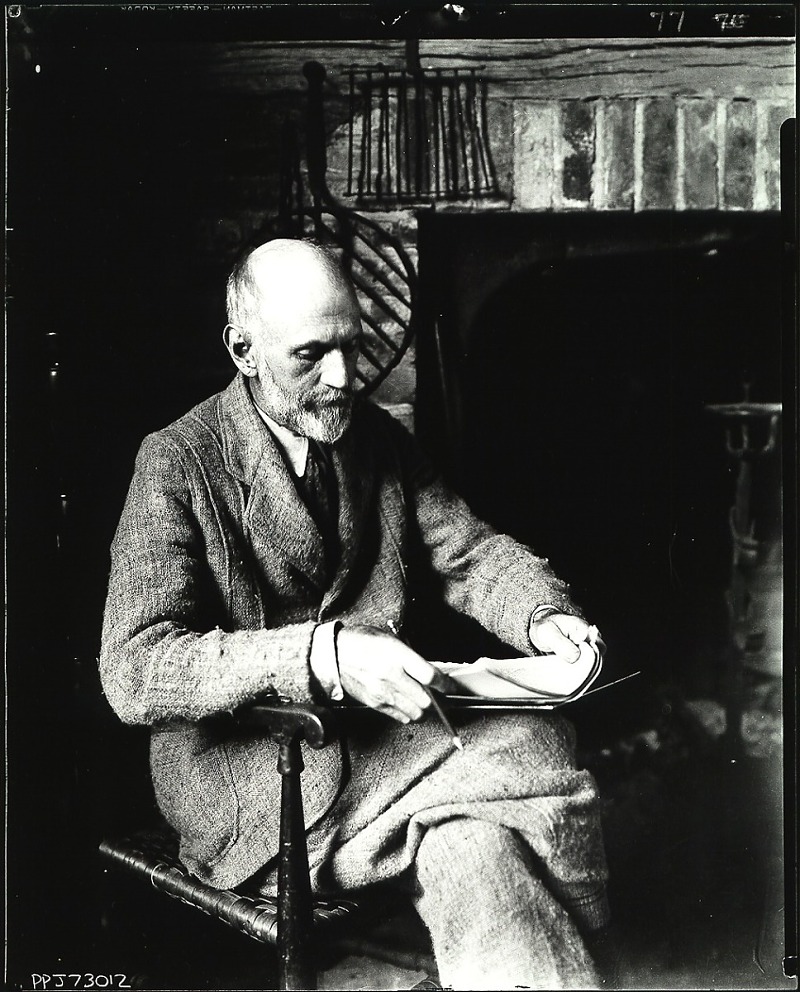

Waugh was an artist from a young age, encouraged in the arts by his father who was also an artist. He studied for a while under Thomas Eakins, one of America’s most famous artists and who pushed the boundaries of his time and challenged the minds of his pupils, like Waugh, urging them to seek their true creative spirit.

Waugh worked in various subjects – even dabbling in works of the subconscious more than 20 years before the surrealist movement – before turning his focus to seascapes. That is, until a stroke of fate brought the young artist and his wife to live on the island of Sark, a tiny island in the English Channel.

It was here that the artist and dreamer had a striking revelation. During a walk in nature with his wife, Waugh was consumed with the harmony of the natural scene before him. The sprawl of the land and glimmer of light entranced and inspired the artist. While the resulting work was a landscape, not a marine work, it reveals the source of true inspiration from which the artist continued to draw:

Moments of beauty in nature, so striking that he felt physically compelled to try to capture them and capture them he did.

Going forward, this compulsion was focused on the sea. The ever-shifting nature of water on rocks was both a constant inspiration and a challenge.

Capturing a Wave

Waugh depicted these moments not in the way that a photograph captures a single, frozen instance in time, but in a way that captures the essence of this moment. He portrays this scene with all of the movement and dynamism of a wave crashing on the shore. With the intangible, ephemeral beauty of beaming rays of light dancing on the water and glistening on the droplets that cling to a rock. With skill that allows the clouds to diffuse the light, causing us to wonder if it is from the sun or perhaps a natural radiance that is then amplified by the warm glowing within our own minds, reflecting the fluttering swell growing in our chests.

The Essence of a Memory

What compels us to take a picture, to make a memory, to choose to lock away the details of a scene in our heads and our hearts to keep and look back on? Is it this feeling? Is it the way that as you focus on the subject of the memory, everything around the edges goes soft and a little blurry? The way the world fades away and for this brief moment in time nothing matters but capturing the essence of this memory.

The Beauty in the Brushstrokes

In this work, we read Frederick Judd Waugh’s brushstrokes from afar as details, but we see up close that’s not the case, they’re large and swashy. The colors that initially read as realistic, begin to take on a stylized hue, a spectrum of purple, pink, green, gold, and white dance in the strokes of the water.

The clouds, a shade of lavender, lined with an almost platinum luminescence.

Waugh didn’t paint en plein air, so as he watched the sea and was struck with this compelling inspiration he locked it away in his memory, visualizing not just the way it looked, but the way it felt. He took that feeling and then transferred it to the canvas.

As we encounter this work, we’re captivated, transported into this scene that perhaps only truly existed in a fragment of imagination. Waugh has invited us to step into his subconscious and experience this scene with him. He shares that visceral pull of inspiration with all of the beautiful blurry imperfections of a memory.

This feels so much like a memory because it is. One that, through this work, we are able to collectively share.

Be sure to watch the full episode here and stay tuned for new episodes the first Friday of each month!