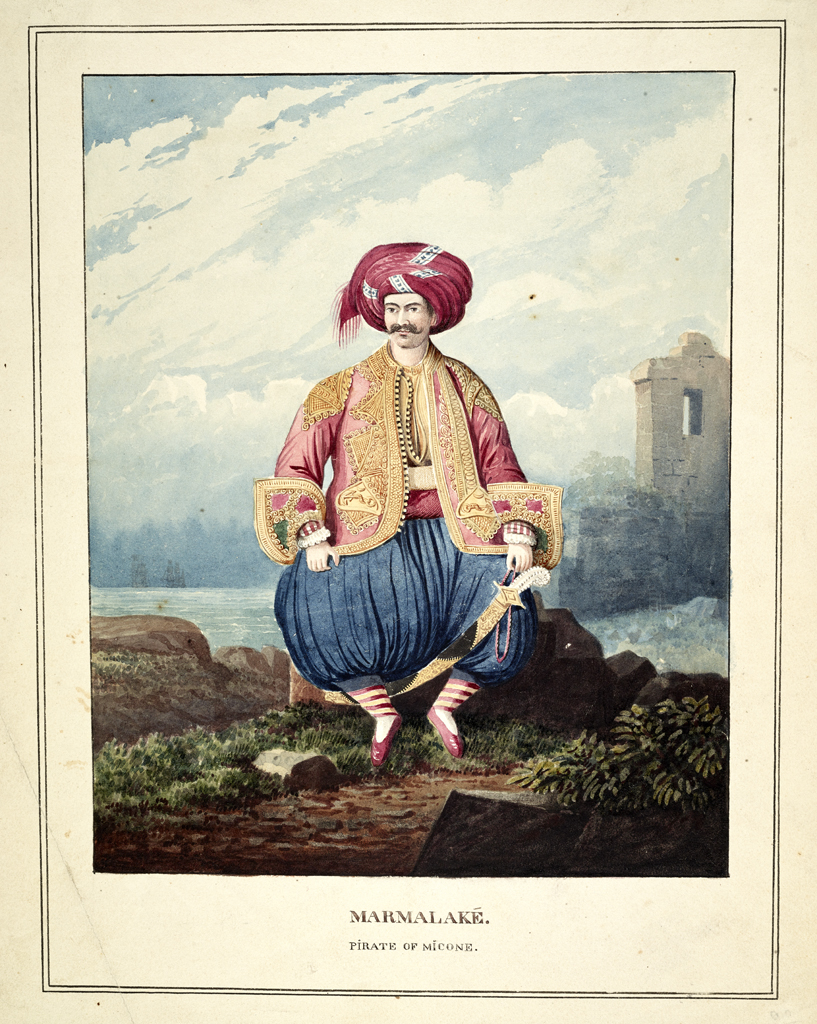

As promised, here is the rip-roaring story of how Manolis Mermelechas, a pirate of Mykonos, Greece, “took” his wife (and I mean “took” literally, not figuratively!). Pay attention Hollywood…there’s a great plot for a pirate movie here!

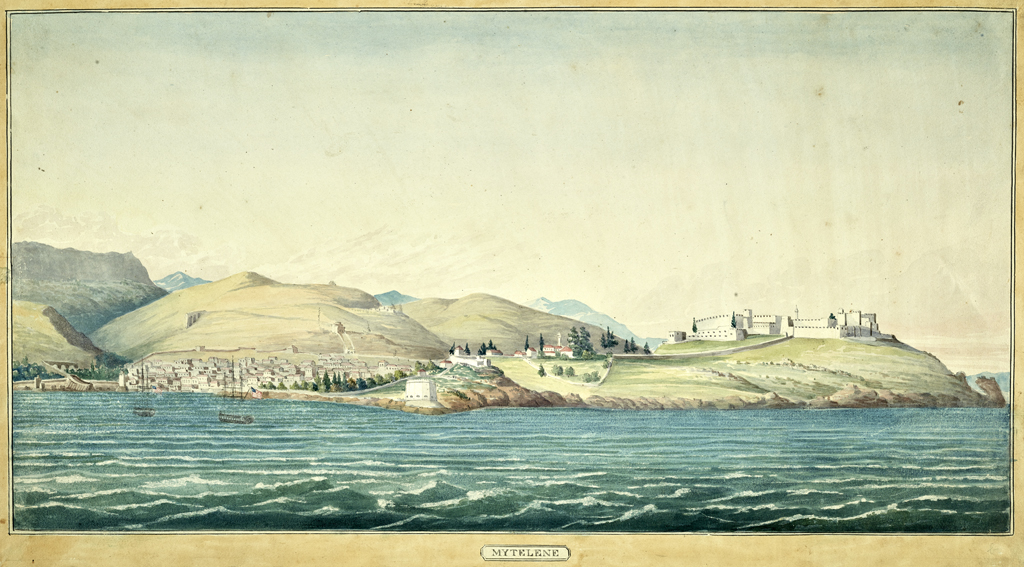

Just in case you didn’t read my last post (which is too bad because Kevin Foster described it as a “ripping great yarn!”), Manolis Mermelechas was a native of the Greek island of Psara who fought against the Turks during the Greek War of Independence. After the Turks invaded and captured Psara in 1824, Mermelechas and his men shifted their base of operations to the pirate haven of Mykonos and continued their attacks on Turkish merchant vessels (and the ships of other countries, hence the designation as pirates!). On one cruise, Mermelechas and his men seized a Turkish merchant ship off the town of Mytilene on the Greek island of Lesbos. It ended up being a capture that changed Mermemlechas’ life forever.

Upon boarding the vessel, the pirates discovered an Italian artist traveling to Turkey with a commission to paint portraits of the family of a wealthy and influential pasha. Among the artist’s possessions the pirates found letters of introduction and correspondence that contained such evocative descriptions of the fame and beauty of the pasha’s daughter, Diamonda, that Mermelechas immediately determined to find the woman and make her his own.

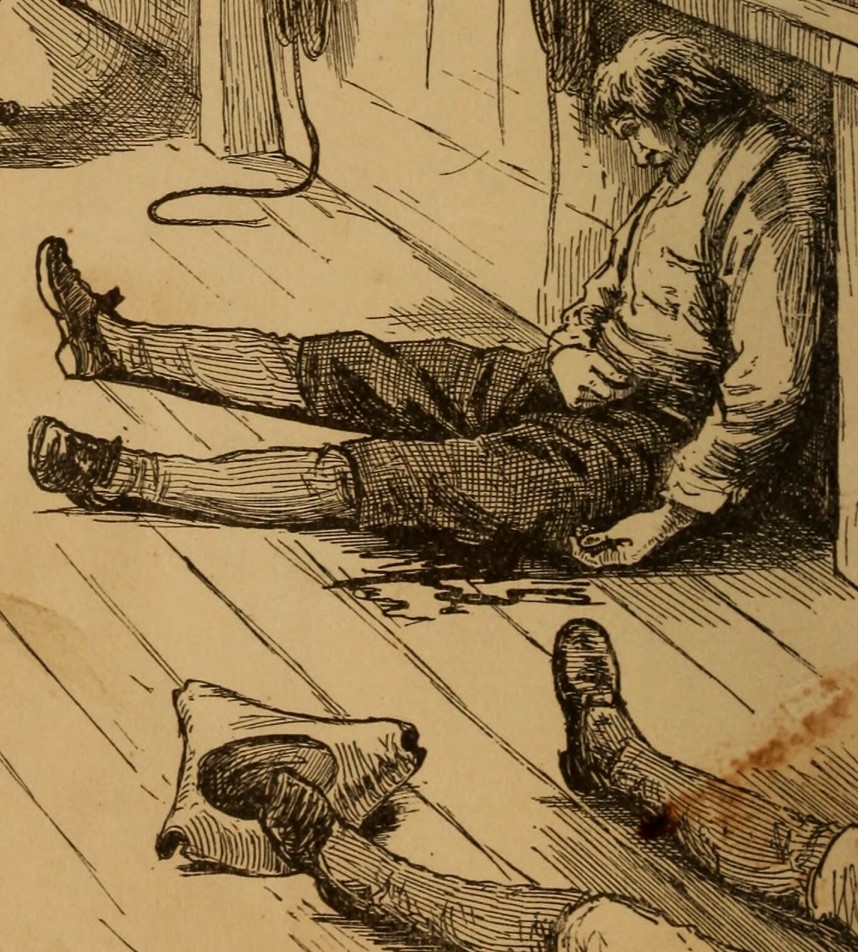

To carry out his evil plan, the pirates murdered everyone on board the unfortunate vessel. They stripped off their clothing, tied ballast stones to their feet and sent their bodies to the bottom of the Aegean Sea. They then destroyed every document or object that might expose Mermelechas’ plan, retaining only those materials that supported the ruse. With the incriminating evidence gone, fifty of Mermelechas’ strongest men, now dressed as Turkish sailors, took their place on board the captured vessel. Escorted by Mermelechas’ fastest vessel, a mystico or tratta that may have been named Bella Vienna, the pirates sailed the captured boat to the Dardanelles in Turkey. The remainder of Mermelechas’ sailed for Mykonos with orders to “occupy the summit” of the island’s tallest mountain and wait for their return.

After arriving at the port closest to the pasha’s residence Mermelechas set the next stage of his plan into motion. Creating the illusion of a band of merchants heading into the country to barter away their cargo, Mermelechas disguised some of his men as peasants and others as traders. Then, loaded down with cargo from the captured vessel, rich presents for the pasha, and a pile of gold to use as bribes, the bloodthirsty band set out for the home of their intended target.

Several days later Mermelechas arrived at the pasha’s residence dressed in the guise of the now dead Italian artist and provided a letter introducing the disguised pirate as “an artist of great distinction” sent by the writer to paint portraits of “his serene highnesses family.” In the letter, the writer explained that the portraits were intended as gifts for the Emperor of Austria, whose friendship towards Turkey during its war with Greece “merited this high distinction and expression of gratitude.” Needless to say, the combination of a highly obsequious letter and the prospect of rich presents ensured Mermelechas was eagerly welcomed into the pasha’s castle.

After delivering the presents and dispensing gold among the pasha’s attendants, Mermelechas began making preparations for taking the first portrait (of Diamonda of course!). Oozing professionalism, the smarmy artist suggested that the best effects of light and shading would be achieved if the portrait was taken with the sitter under an arbor in the garden. With the father’s agreement, an appointment was made to begin the portrait the following day.

The next morning Mermelechas entered the gates of the castle seemingly prepared to begin the portrait, but actually only intending to get his first view of the beautiful Diamonda. Satisfied that the tales of the woman’s beauty had not been exaggerated, he pretended to be indisposed from his long journey and asked to postpone the first sitting until the next day whenever it was most convenient for Diamonda. It was agreed that she would sit for the sham artist after her morning ride and that “she would be taken” in her riding dress. This literally proved true as Mermelechas spirited the girl away–in her riding clothes–at six o’clock the next morning.

While Mermelechas managed the acquisition of his “beauteous prize,” his men were working on another aspect of the pirate chief’s plan—the emptying of her father’s coffers. So, as the poor girl was forced-marched all day and night to the port where Mermelechas’ escape craft was moored, his men found their way into her father’s treasury and scurried away loaded down with gold, jewels and precious stones.

When the solid and human treasures were safely embarked on board Bella Vienna, the pirates sailed for Mykonos (the slower Turkish merchant ship was left behind to fend for itself). The oarsmen, keeping time by chanting a war song, swiftly propelled the boat over the calm Aegean. Mermelechas stood on the deck with his fist clenched tightly around the hilt of his sword prepared to defend his lovely prize. The pirate’s careful planning had ensured a quick escape and “rendered pursuit as useless as attack would prove dangerous.”

Interestingly, the pirates noted that Diamonda never openly lamented the situation and only appeared “somewhat sad” about leaving her family–not exactly a normal reaction for a beloved daughter kidnapped by pirates! By the time the ship reached Mykonos it was said that “all the ferocity of the pirate was melted down by the genial rays of beauty [Diamonda] shed upon him.” Translation: Mermelechas was whipped…an ooey, gooey smitten mess of a man.

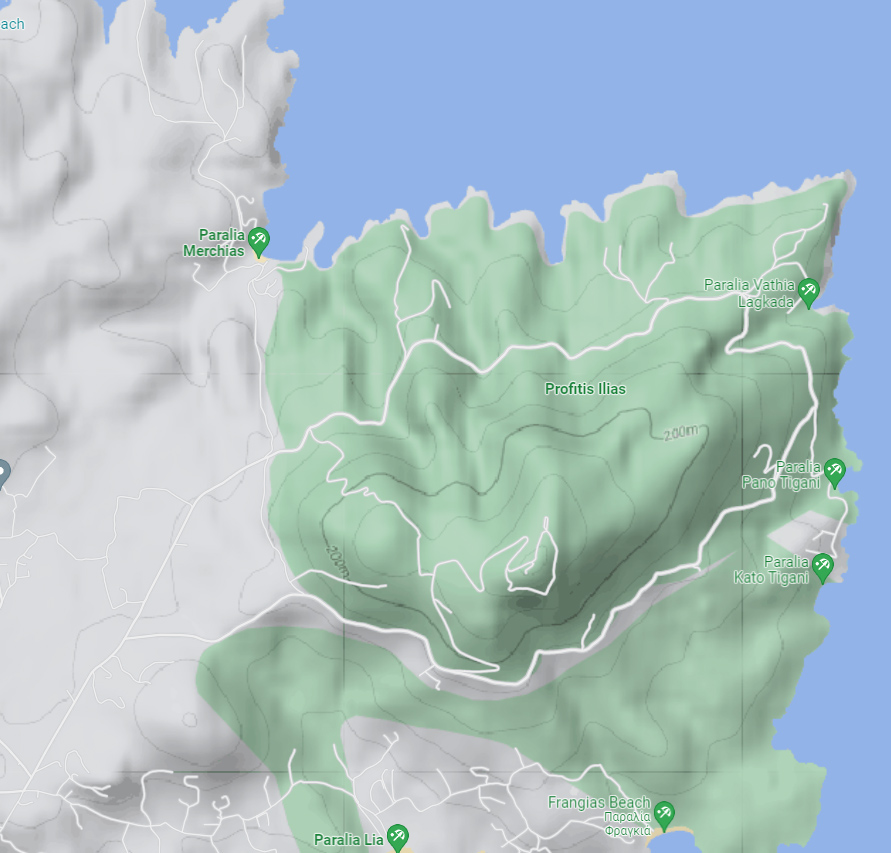

Arriving at Mykonos the pirates entered a small secluded bay on the north side of the island that sat at the base of Mount Vorniotis. The summit of the mountain, called Profitis Ilias, which sat “amid the rolling clouds” surrounded by a steep precipice on all sides, was the secure location Mermelechas had chosen as the group’s hideout. Sailing their boat through an “intricate hidden pass” with high steep walls known only to the pirates offered complete secrecy and security for their little fleet and made pursuit nearly impossible. Just to make doubly sure the boats were fully concealed, the pirates rolled a large rock over the entrance of the bay. When the men waiting for their return saw the arrival of their chief their “enthusiastic cheers…echoed and reverberated down the deep ravine” they traveled through to reach the bay.

Once this place of safety was reached, Mermelechas scooped his beautiful, blushing Diamonda into his arms and leapt over the bulwark onto the sandy beach. Upon seeing the beautiful captive lightly dropping from the arms of their chief the men unsheathed their ataghans (a type of short Ottoman saber), crossed them over her head, and with hands over their hearts pledged to devote “themselves, their lives, and their fortunes” to her. Then, standing in a circle around the couple, the men bowed and thrice touched their foreheads to the ground to “invoke blessings upon them both, from the patron saints of their respective isles.”

With the boat secured, the party packed up as much as the treasure as they could carry and began the long difficult climb up the side of the mountain. To conceal their movements, they only traveled up the deepest ravines. After several hours they reached the precipice that surrounded the mountain’s summit. At its foot stood a church and small hut that guarded the entrance of a cave. Sitting nearby was an old gray-bearded priest trimming the wick of a candle whose sole occupation was “to trim the midnight lamp” of the watchtower and to pray and watch, all day and night.

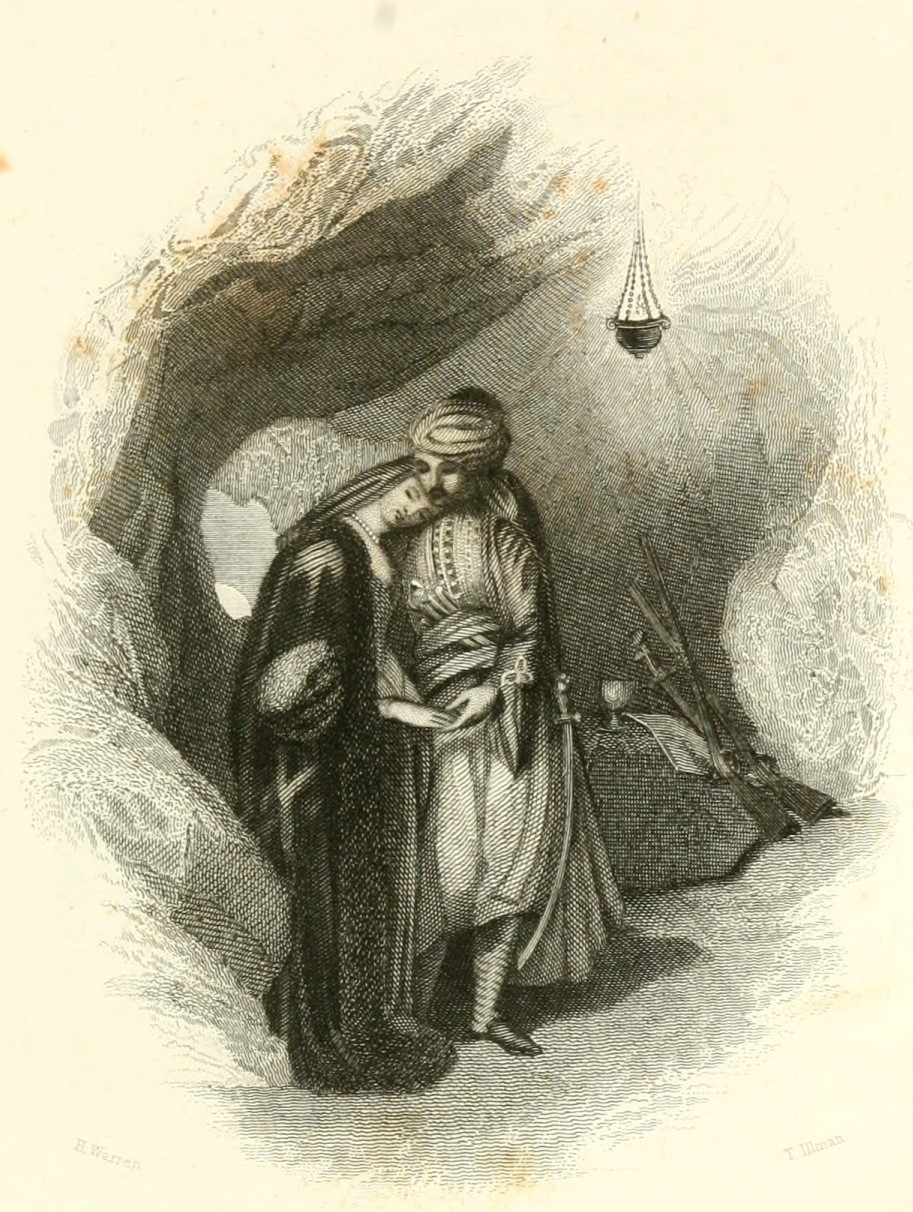

While his men sat outside dividing their plunder and recounting their adventures to those who missed out on all the fun, the priest, with his rosary in one hand and a lamp in the other, led Mermelechas and Diamonda into his cell muttering benedictions as he went. Settling his trembling bride-to-be on a couch, Mermelechas turned to the priest and asked him to prepare some refreshments and then join them in the holy bonds of matrimony. At this point the newly lit taper, which had only cast a dim light throughout the room, roared to life and illuminated Diamonda’s face, and in it the priest discovered his long lost daughter!

While the father and daughter happily reconnected, the pirates, driven by hunger and fatigue, entered the mouth of the cave and after winding their way through a seemingly endless labyrinth, arrived at the mountain’s summit and their well-guarded and well-supplied hideout. Unfortunately, the storyteller never learned the story of how Diamonda was separated from her father nor the details of how she was adopted into the family of the rich and powerful pasha (we’ll just have to use our imagination for that part!). The next morning, the father happily wed his daughter, not to her captor but to her rescuer.

When the story was published in 1828, it was reported that Diamonda had lost some of her beauty from “exposure in following the fortunes” of Mermelechas, but she was still considered a “goddess among the mountains of Miconi” and remained faithful to her husband. Unfortunately, “following the fortunes” of her husband involved “frequent depredations upon the American vessels trading to the Levant.” As a consequence, the US Navy was actively roving over the island of Mykonos trying to capture the couple. The writer, obviously someone actively involved in the search, reported that large bounties and bribes were offered to reveal the couple’s whereabouts, but they were always rejected with contempt. To me this proves that Mermelechas’ men remained true to the oath they had sworn to his wife.

This story was originally published in the New-England Galaxy and United States Literary Advertiser on April 25, 1828. Over the next few months it was reprinted in other newspapers around the country. The author of the article used the pseudonym “Paul Jones Jr.” but it seems certain it was most likely Joseph Partridge, the artist of the portraits. It seems that Partridge recognized that parts of Mermelechas’ tale bore a remarkable resemblance to Lord George Byron’s “The Corsair” which was published in 1814 and was very popular in the United States. While we’ll never know for sure if the story is true or fabricated by Partridge, many of the published details are certainly rooted in fact. The creation of the two beautifully detailed portraits of the story’s protagonists reveals that the artist was enamored with the couple’s romantic tale as well as Mermelechas’ piratical exploits–even though he may have been involved in trying to stop them.

If you want to read the original story here is a link to our catalog record: https://catalogs.marinersmuseum.org/object/CL12748

Thanks to the early 19th century way of speaking and total lack of editorial organization it’s a little convoluted and hard to interpret but totally worth the time!