I am the Student Program Coordinator on the Education Team at The Mariners’ Museum and Park. As you can imagine, a big part of my job is scheduling our educational programs for students. The great thing for me is I also often have the privilege of corresponding with people who are seeking information or asking questions. Thankfully, I don’t have to answer everything myself. I have the constant support of the rest of our Mariners’ family. Let me give you an example by taking you on a journey with me.

Several months ago I was contacted by Pam Cameron. Mrs. Cameron was doing research about lead lines for a project she was working on. I will tell you more about lead lines in a moment, but first I have to share something else. In the course of our conversations, Mrs. Cameron shared that she was the author of Sport: Ship Dog of the Great Lakes. This is a book that takes place on the lighthouse tender Hyacinth pictured below. In 1914, the crew of Hyacinth rescued a stray puppy that they named Sport.

I shared Mrs. Cameron’s information with Lauren Furey, our manager of visitor engagement, who hosts our Maritime Mondays program. She already had Sport: Ship Dog of the Great Lakes on her list for this fall. In fact, if you would like to hear more about Sport’s adventures and lighthouse tenders, you can join Lauren for Maritime Mondays on Monday, September 13. You can register here.

This is the book if you would like a copy of your own.

Now the information about lead lines that I promised. A huge thank you to Marc Nucup, our public historian, for providing much helpful information

The lead line was used by sailors to assess the depth of the water and take samples of the sea floor. The line was thrown over the side of a vessel and the lead was allowed to sink to the bottom while the end of the line was held by the sailor. Red, white, and sometimes black strips of cloth or leather would be attached to the line approximately every six feet or fathom. The bottom of the lead was made in a concave shape and filled with something sticky like animal fat. This would allow the sailor to bring up samples from the bottom.

Lead lines have been used since the 5th century BCE. Some mariners still keep a lead line on board their vessel today. It’s a great backup that needs no batteries and never needs to be recalibrated.

Amazingly enough, discovering more about the lead line brought me back to another author. In the course of communicating with Mrs. Cameron, Shannon Ricles, the education and outreach coordinator for NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary, shared an article about Mark Twain.

Most of you probably know that Mark Twain was born Samuel Clemens. On April 9, 1859, he became a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi River.

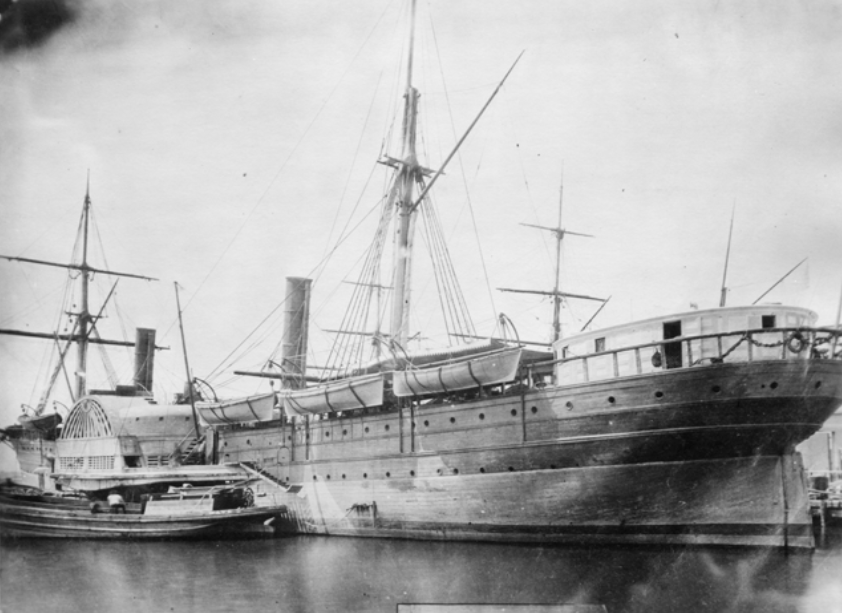

This is Arago, one of the steamships that he piloted.

During Mark Twain’s time on the Mississippi, the markings for the different depths of the lead line had different names that were sung after a measurement or sounding was made. Twelve feet above the lead or twelve fathoms was called “safe water.” The name that was sung was Mark Twain. Samuel Clemens chose the name Mark Twain from his experience with the lead line used on the Mississippi River!

That completes my journey from scheduling students to Mark Twain with stops for a wonderful account of Sport the rescued dog and lead lines along the way. I hope you have enjoyed the adventure.

We love connecting people to the water, to each other and to our collection. You can easily access our collection. If you need help with research, our library team will be happy to assist you.