Have you ever gotten the sense that something is following you around? Maybe there is a phrase, word, song, or something else that just keeps popping up in unexpected places, and you’re not sure why? That happened to me recently, and the product is this blog post!

It started with a research project. You see, I was recently reading through the final draft of a book that I edited with Dr. Jonathan White, entitled My Work Among the Freedmen: The Civil War and Reconstruction Letters of Harriet M. Buss. For this book, I transcribed the correspondence of Harriet Buss, a teacher from Massachusetts who moved to South Carolina during the Civil War to teach freed people. Buss wrote to her parents regularly, and was detailed in her description of her travels. In traveling back and forth from New England to the coast of South Carolina throughout 1863, Buss frequently boarded the Steamer Arago, and several of her letters bear this heading! When I first transcribed these letters, I honestly didn’t think much about the fact that she was on the Steamer Arago, beyond the contextual research on the vessel. I found her descriptions interesting, and her tales of travel occasionally amusing. I also gagged a little when she described the “quart tin vomiting cup” that accompanied every berth on the ship. [1]

Fast forward to earlier this week, as I was perusing The Mariners’ Museum’s catalog. As a historian with particular interest in the Civil War, I was excited to find a set of letters from a Union soldier named Michael Guinan. I was pleasantly surprised to see that while Guinan was stationed in Newport News, he was aboard Arago! Small world, I thought!

The story continues as I perused the Museum’s blog to read the articles that were published in the past few days. I read through Jane Jones’ post entitled “Scheduling Students, Lead Lines, and Mark Twain.” While I was intrigued by this title, I was not expecting to find any major connection to my own research in this array of topics! I should not have doubted… In the article, Jane discusses Mark Twain’s experience as a steamboat pilot. (Side note: did you know that The Mariners’ Museum has one of his pilot’s licenses in our collection?) I knew that Mark Twain was a steamboat pilot, but can you guess which steamboat he piloted? You guessed it, Arago. “Could this be the same ship in all three situations?” I thought to myself. This is where having a background in research, as well as fantastic archives at your fingertips, comes in handy. I decided to find out if, by some chance, this one steamboat had been following me around. My journey started with reading about this vessel’s life on the water.

“A VERY FIRM AND FINE BOAT”

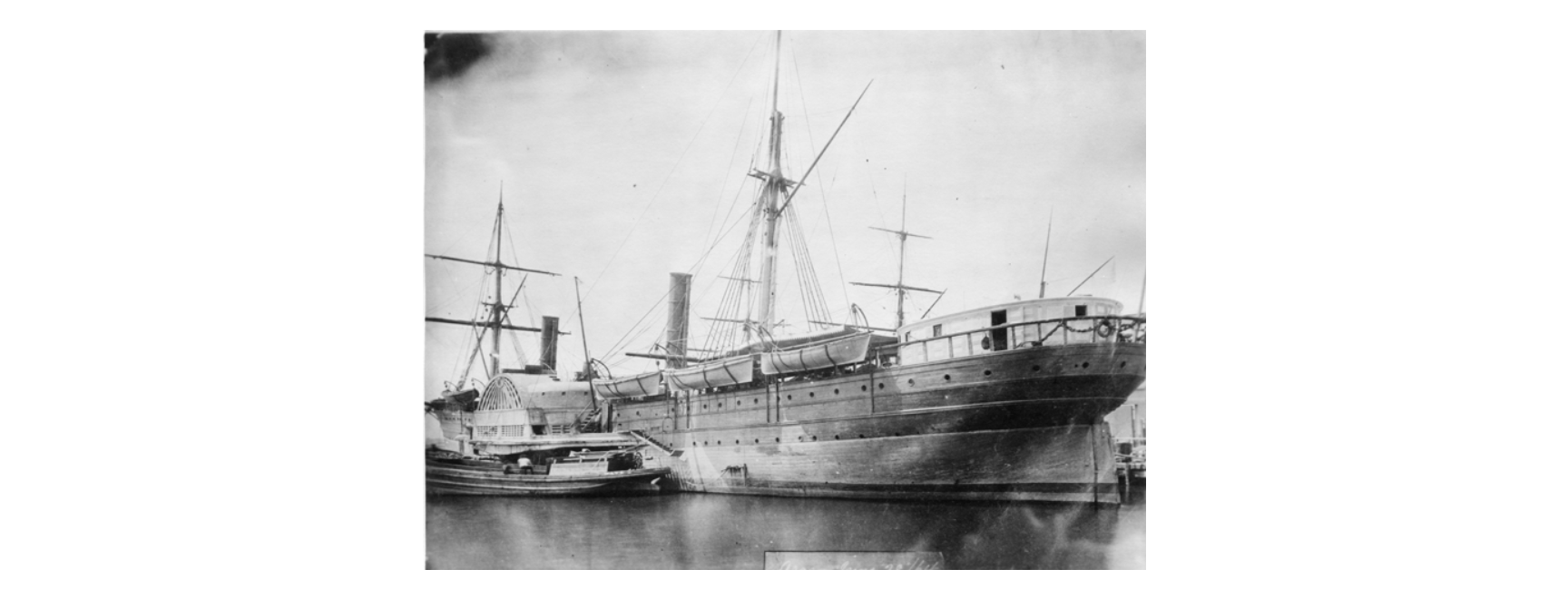

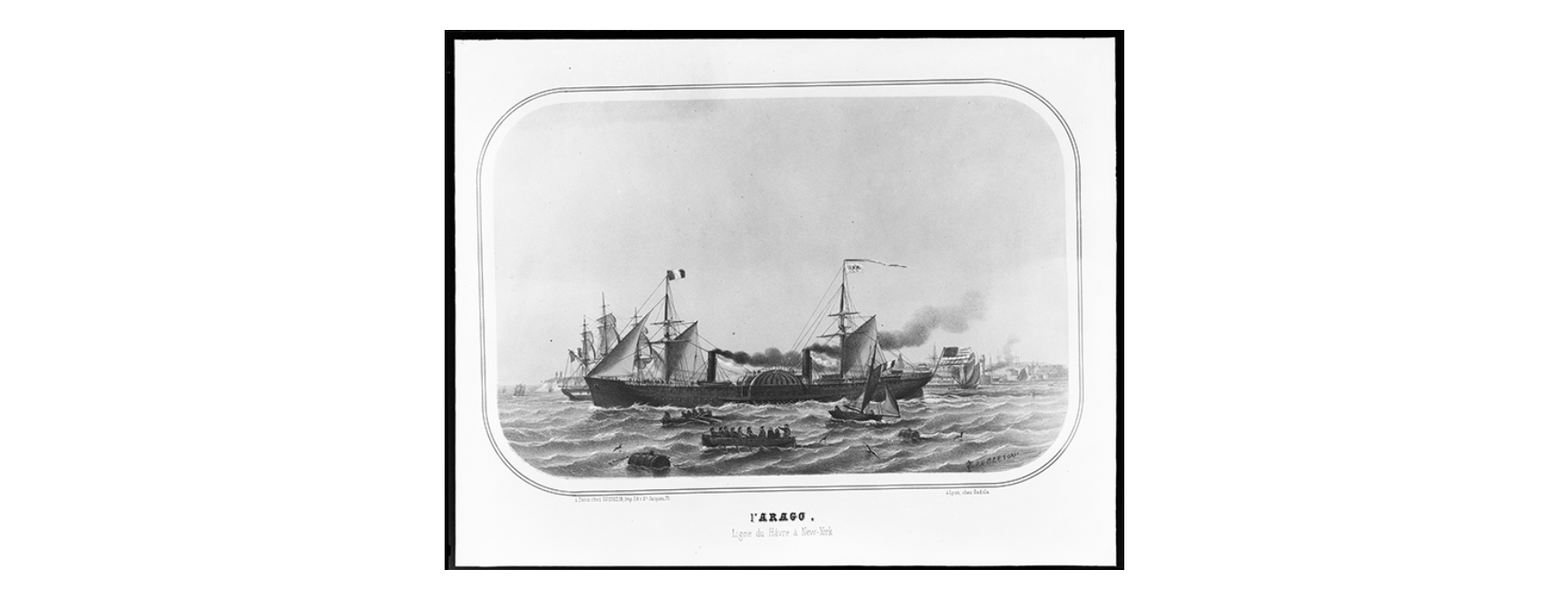

In January of 1855, The Daily Union, a newspaper out of Washington D.C., published an announcement that “The Steamship Arago will be launched from the yard of Jacob A. Westervelt’s Sons & Co. at the foot of Seventh street, East river, at 2 o’clock.” Built by Westervelt & Songs in New York, New York, Arago, a wooden hulled, side-wheeled steamer, was an innovative piece of technology. In 1855, this type of vessel was a great improvement to its predecessors with a pair of oscillating engines. [2] The Daily Union went on to say that Arago was “one of the largest steamers yet built, being about 3,000 tons, and a fine model both for speed and capacity.” [3] Harriet Buss, in a letter to her parents, seemed to agree with the newspaper’s assessment. In March of 1863, she wrote that “The Arago is a very large vessel and said to be a very firm and fine boat.” [4] Arago’s purpose was to operate as a transatlantic mail carrier, and from 1855 to 1861, would transport mail, cargo, and passengers between ports in New York and Europe. In 1861, Arago and her sister ship, Fulton, were chartered by the U.S. Government at the onset of the Civil War as a transport vessel for Union soldiers. [5]

Between March and April of 1862, following the Battle of Hampton Roads, Arago’s charter was transferred from the War Department to the U.S. Navy for a special operation. Arago, Vanderbilt, Illinois, and Ericsson sailed to Hampton Roads, without telling their civilian crews the purpose of their journey. The goal was that if CSS Virginia were to again be put out on open water, Arago, along with the other vessels, would ram Virginia. The Daily Green Mountain Freeman, a Vermont newspaper, referred to Virginia by her previous name,USS Merrimac, and wrote that “should she again appear in Hampton Roads, the steamers Vanderbilt and Arago are also to be employed in the experiment of running down the rebel craft.” [6] Upon arrival in Hampton Roads, the civilian crews of Arago and Iliinois learned of the special orders. The Salt Lake Herald detailed this story in an 1896 article, writing “Knowledge of these orders some way got to the crew at night. The next morning, except his officers he had not a man on board. His crew had deserted in a body.” [7] Learning of their perilous orders, the crew ran, leaving the captain to determine how to complete this mission. According to the Salt Lake Herald’s account, the captain turned in desperation to the Quartermaster in charge of the “contraband camps” at Fort Monroe for assistance. The Quartermaster then returned with 350 African-American men from Fort Monroe, willing to serve on board Arago if needed. [8] As this occurred before the Emancipation Proclamation, these men were technically still enslaved, but yet were willing to risk their lives in support of the Union.

It was after this point, in November and December of 1862 when Arago was back in the service of Army Transport, that Michael Guinan, a 23 or 24 year old member of Company A, 128th Regiment New York Volunteers, was aboard Arago. On November 7th, 1862, Guinan wrote to his sister Eliza Guinan that “we have been on board since the night before last…it is the talk here that we are going down to Fortress Monroe and there wait until the fleet all start together it is rumored that we are going down to [C]harleston…to capture that place.” [9] Throughout his correspondence in the fall and early winter of 1862, Guinan describes his experiences stationed in Newport News. He writes about the remains of USS Cumberland and Monitor, and describes daily life both aboard Arago and on shore at Fort Monroe.

For the remainder of the war, Arago returned to serving as transport for mail, equipment, and passengers, and traveled along the East Coast from Charleston to New York City. [10] Through the research I have done, I am led to believe this is the same vessel that Harriet Buss traveled on throughout 1863, as Buss repeatedly refers to Arago as a mail transport ship, and this is the method by which many of her letters are sent and received between her and her parents. In July of 1863, as Arago ferried sick and injured soldiers from the battles of Fort Sumter and Fort Wagner, she overtook and captured the Confederate blockade runner Emma. [11] Throughout the remainder of the war, Arago continued her original transportation duties, transporting the Fort Sumter flag in 1865. In 1869, she was sold to the Peruvian government.

Satisfied with my exploration of Arago’s history thus far, and the connection to both Michael Guinan and Harriet Buss, I turned to the third potential connection: Mark Twain. Twain, or Samuel Clemens, began his apprenticeship to be a steamboat pilot in 1859, and earned his official license in 1861. The timeline of his career as a pilot, therefore, would align with the civilian career of Arago. I determined that Twain did indeed pilot a steamship named Arago from July 28 to August 31st, 1860. [12] [13] Again, this potentially lined up, and I was hopeful. This Arago, however, was built in 1860, and was owned by the St. Louis and Vicksburg Mail Packet Line. [14] Further research on Twain’s Arago revealed that this sidewheel steamer was built in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, and in 1865, caught fire and burned. [15] This told me all I needed to know. I have to admit, I was disappointed that it was not the same steamboat. There was definitely a part of me that hoped the story would continue, and there would be a unique connection between Harriet Buss, Michael Guinan, and Mark Twain!

Despite the fact that my rabbit hole of research did not come to the conclusion I hoped for, I think it was profitable, as it shed light on new aspects of Civil War history in Hampton Roads. The story of Arago demonstrates how maritime history creates unexpected connections. It revealed the bravery of African-Americans of Fort Monroe, the voice of Michael Guinan, and built a connection to Harriet Buss, a woman determined to teach freedpeople. While it eventually did not include Mark Twain, it was a fun adventure for me to explore, and if you have stuck with me thus far, I hope readers enjoyed this as well!

ENDNOTES

1 Harriet Buss to parents, March 23 1863. In My Work Among the Freedmen: The Civil War and Reconstruction letters of Harriet M. Buss eds. Jonathan White and Lydia Davis (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2021), 2.

2 John Harrison. The History of American Steam Travel. (New York: W. F. Sametz & Co., 1903), 411.

3 The Daily Union, (Washington D.C.) January 26th, 1855.

4 Harriet Buss to parents, March 25 1863. In My Work Among the Freedmen: The Civil War and Reconstruction letters of Harriet M. Buss ed. White & Davis (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2021), 5.

5 John Harrison. The History of American Steam Travel. (New York: W. F. Sametz & Co., 1903), 411.

6 The Daily Green Mountain Freeman, (Montpelier, VT) April 2 1862.

7 “Crucial Test of the Black Race” The Salt Lake Herald. (Salt Lake City, UT) March 22, 1896.

8 Ibid.

9 Michael Guinan to Eliza Guinan, November 7th, 1862. The Mariners’ Museum Collection.

10 United States Congress (1902). Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 60.

11 Ibid. 399.

12 Mark Twain’s Letters, Volume 1: 1853-1866. Ed. Branch, Frank & Sanderson. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987) 389.

13 Edgar M. Branch. “A Proposed Calendar of Samuel Clemens’s Steamboats, 15 April 1857 to 8 May 1861, with Commentary.” Mark Twain Journal 24, no. 2 (1986): 2–27.

14 Mark Twain’s Letters, Volume 1: 1853-1866. Ed. Branch, Frank & Sanderson. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987). 101.

15 “Arago (Packet: 1860-1865)” University of Wisconsin – LaCrosse Historic Steamboat Photographs. University of Wisconsin Libraries.