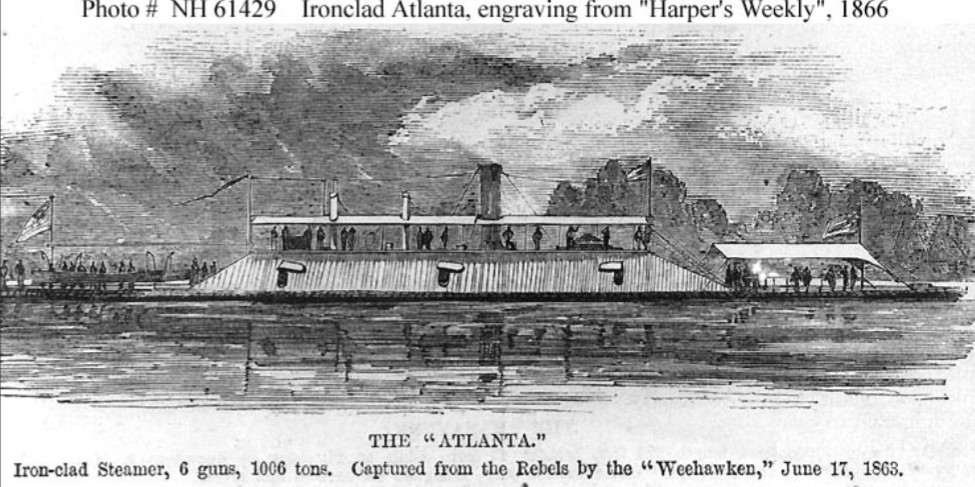

CSS Atlanta was an ironclad transformation effort which used the iron-hull and Scottish-built engines of SS Fingal to fashion one of the Confederacy’s most powerful warships. The ironclad; however, had a deep draft which limited its operational area below Savannah. This coupled with a very rash and impetuous captain, Commander William Webb, resulted in Atlanta’s capture in a brief engagement with the monitors USS Weehawken and USS Nahant. The ironclad soon became the USS Atlanta and served until 1865 in the James River. It was later sold to Haiti and floundered en route without a trace.

SS Fingal

The Atlanta had its genesis from the merchant ship SS Fingal. This merchant ship was constructed at the J & G Thomson’s Clyde Bank Iron Shipyard at Govan in Glasgow, Scotland. The Fingal’s dimensions were:

Tonnage: 700 tons

Length : 189 ft.

Beam: 25 ft.

Draft: 15 ft.

Propulsion: one shaft, two direct-acting steam engines powered by one flue-tubular boiler.{1]

The merchant ship was built for and operated by Hutcheson’s West Highland Service until purchased by Commander James Bulloch, one of the Confederate agents operating in Great Britain. He described Fingal as “a new ship; had made one or two trips to the north of Scotland, was in good order, well-found, and her log gave her speed as thirteen knots in good steaming weather.” [2]

Secret Planners

Bulloch, a former US Navy officer and merchant ship captain, had acquired the steamer in league with Major Edward Clifford Anderson. Anderson was a former naval officer who had been appointed a midshipman in 1823 at the age of 18. He served with distinction during the Mexican War aboard USS Mississippi commanded by Commodore Matthew C. Perry. Anderson resigned his commission in 1849 and returned to Savannah where he became mayor of the city prior to the Civil War. At the war’s onset Confederate president Jefferson Davis dispatched him to Great Britain as an agent to purchase war materiel for the new Southern nation. He was considered the ‘Confederate Secretary of War in England.’[3]

Escape

Accordingly, as Anderson acquired a massive amount of military supplies Bulloch arranged for Fingal to secure British officers and crew. The ship was loaded and slipped out of Greenock, Scotland, on October 8, 1861, with Holyhead, Wales, as the destination. Bulloch and Anderson joined the ship there as they needed to confuse the Union spies following them. As the blockade runner left that port in the dark on October 14 and 15, it rammed and sank the Austrian brig Siccardi which was slowly swinging at anchor without any lights. Bulloch instructed Fraser, Trenholm & Co. to settle the issue so that Fingal would not be retained. [4]

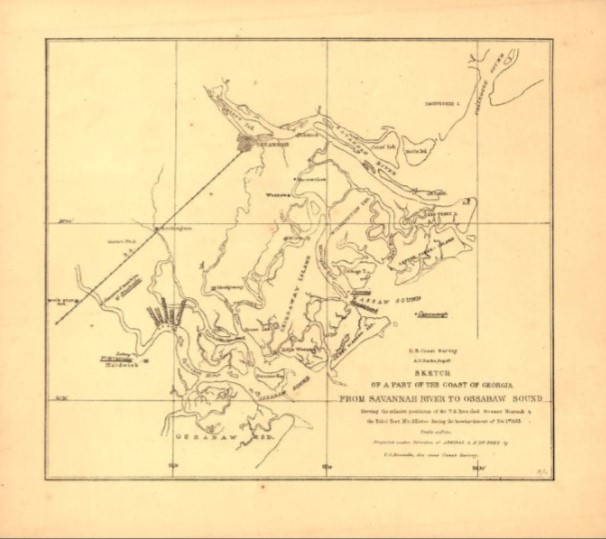

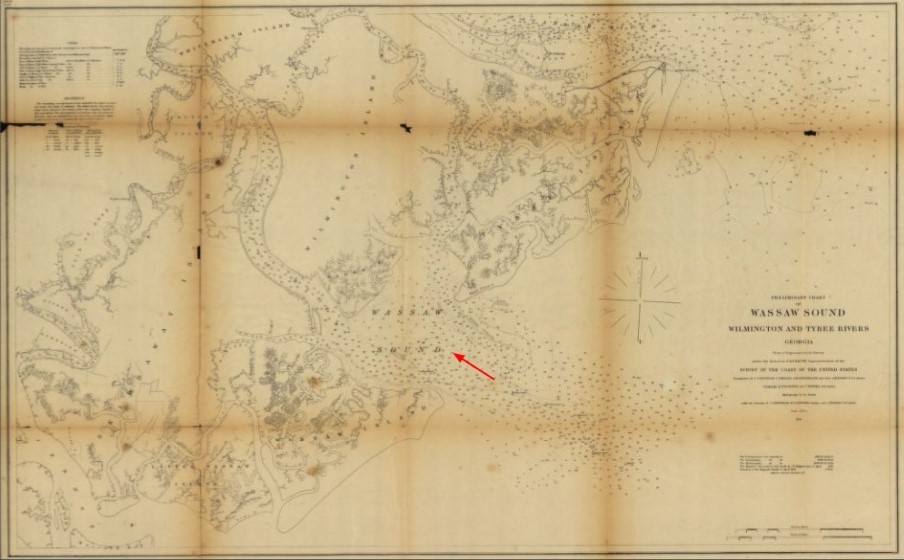

When Fingal reached St. George, Bermuda, Bulloch met with Lieutenant Robert Pegram, captain of the commerce raider CSS Nashville and secured the services of that ship’s pilot, John Makin. Bulloch induced all of the British officers and crew to stay with the ship and help run the blockade into Savannah. The Fingal was then turned into somewhat of a fighting ship by hoisting out of the hold two 4.5-inch rifles and two boat howitzers. These guns were mounted and the crew was armed with muskets, revolvers, and swords. Despite these defensive preparations, Fingal was able to pass into Wassaw Sound during the foggy night of November 12, 1861. [5]

Goods Delivered

When Fingal reached Savannah, there was great joy as the steamer was the first ship to run the blockade inbound loaded with supplies just for the Confederate government. The cargo was a godsend to the Confederates. The cargo consisted of 10,000 Enfield rifled muskets, 1,000,000 ball cartridges, 2,000,000 percussion caps, 3,000 cavalry sabres, 1,000 short rifles and cutlass bayonets, 1,000 rounds of ammunition per rifle, 500 revolvers and ammunition, a couple of large rifled cannons and their gear, and a vast amount of medical supplies and clothing material. [6]

“No single ship,” Bulloch later noted, “ever took into the Confederacy a cargo so entirely composed of military and naval supplies.” He also noted the great importance of these supplies “because the Confederate army, then covering Richmond, was very poorly armed and was distressingly deficient in all field necessaries.” [7]

Trapped

Bulloch then prepared Fingal for a return voyage to Great Britain loaded with cotton; however the Federals learned that this blockade runner was ready to attempt an escape. Unionists had occupied Tybee Island and placed blockaders at every possible exit from Savannah. On December 23, Bulloch took Fingal down to Wilmington Island to find an unguarded exit; but they were all vigorously guarded by Federal ships. Secretary Mallory decided in early January 1862 that Bulloch should return to Great Britain by other means and that Fingal should be converted into an ironclad ram.[8]

The Tift Brothers Take Charge

Mallory selected his friends Nelson (Albany, Georgia) and Asa (Key West, Florida) Tift, to convert Fingal into the ironclad ram Atlanta. Despite the Tifts not completing CSS Mississippi to defend New Orleans, the secretary had total trust in the brothers. The Tifts had made several errors with their first ironclad project; nevertheless, Mallory gave the men overall control for the transformation project. They were not shipbuilders but businessmen. Asa was the leading salvager in Key West and operated a small ship repair yard. Nelson was the founder of Albany, Georgia, and a three-term member of the Georgia House of Representatives. During the war, Nelson, when not building ironclads, was a captain in the Confederate Navy supply department and also provided the Confederate army with food and other supplies.

Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall, the last commander of CSS Virginia and now commander of the Savannah Squadron was thoroughly dismayed when the Tifts were made completely in charge of this conversion project. He wrote Mallory, “Mr. Tift, who was in charge of construction, called at my office and showed me his authority…giving him sole control of her construction, and, in reply to a question, he stated that it was intended that the commandant of the station should have nothing to do with her. I, of course, abstained from interfering in any shape whatsoever.”[9]

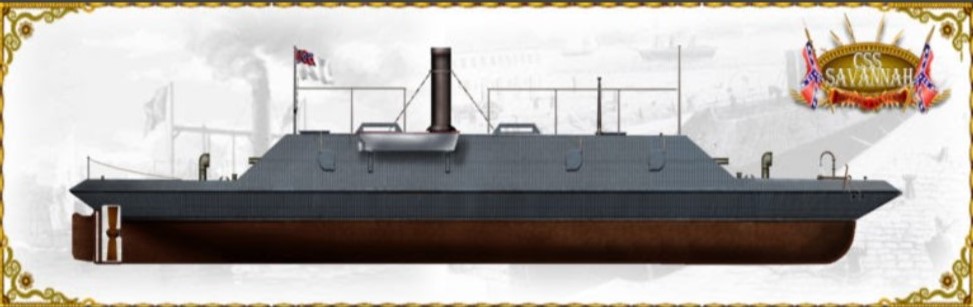

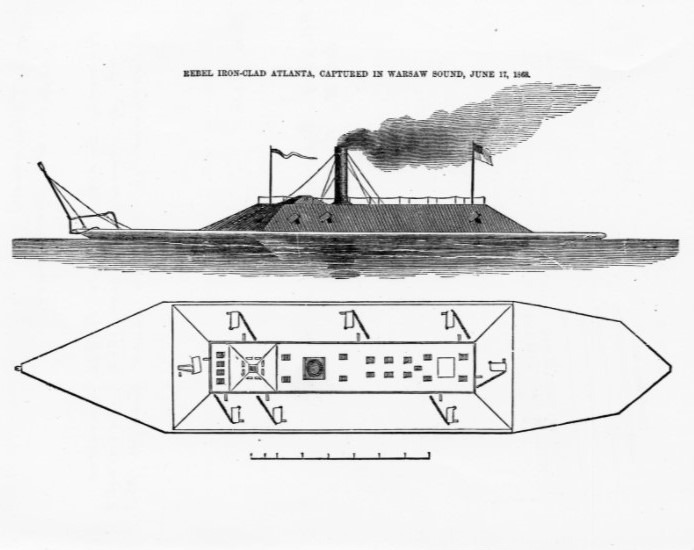

The Conversion

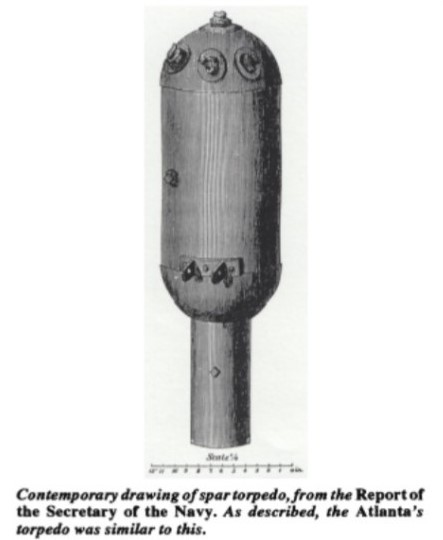

Work on the conversion began in earnest in February 1862, and the ship was ready for trials by July 1862. The vessel was cut down to her main deck, and a platform 3 ft. in thickness was installed 7 ft. above the waterline. Sponsons were built out from the sides of the hull to support the ironclad’s casemate, which sloped at a 30-degree angle. [10] The casemate was constructed of 3 inches of oak and 15 inches of pine over which two layers of two-inch iron, seven inches wide, were laid and bolted together by bolts one and ¼ inches in diameter, countersunk with nuts and washers. The shield extended several feet below the waterline. The ship was formed into an iron beak. The bow was also fitted with a wooden pole that had a 50-pound percussion torpedo operated by an iron lever and pulleys at its end. [11]

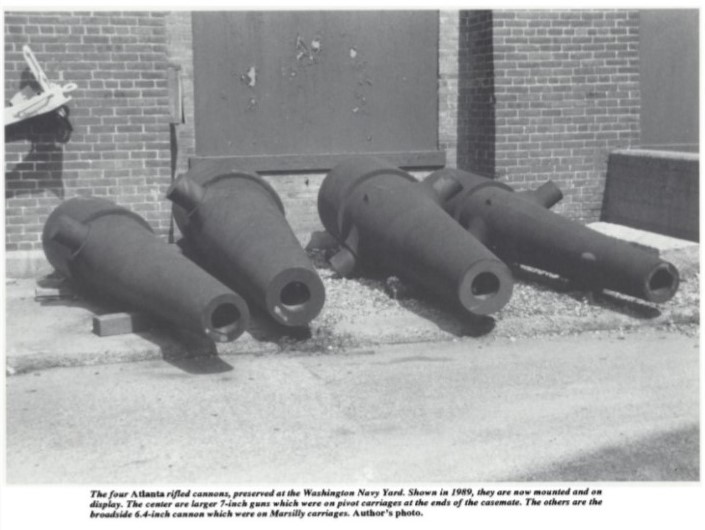

The Atlanta was also armed with two 7-inch Brooke rifles weighing 15,300 lbs on pivot mounts with three gunports at bow and stern. The broadside guns were two 6.4 inch Brooke guns. All of these Brooke guns were single-banded. The eight gunports were very small and only permitted slight lateral aiming and the ability to elevate the rifles from 5 to 7 degrees. A two-inch iron port shutter protected each gunport.[12]

Atlanta’s Dimensions

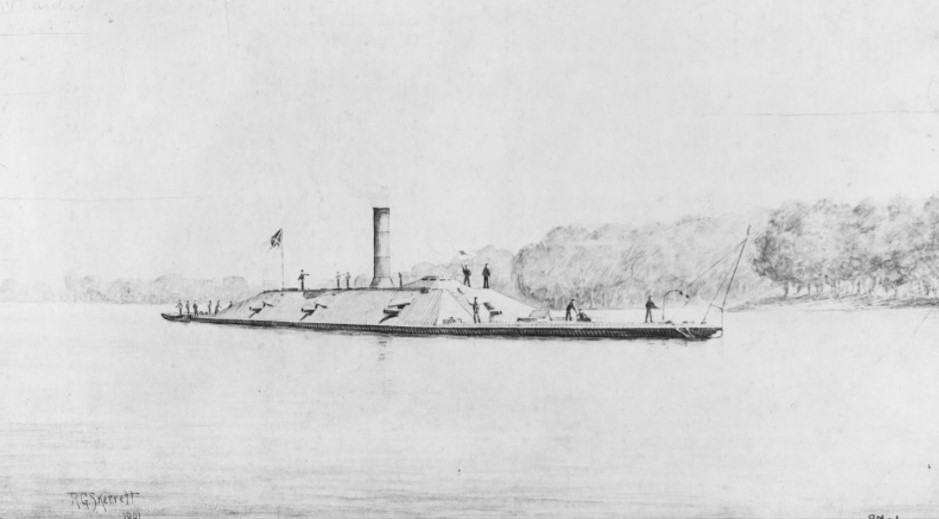

Artist unknown. The Mariners’ Museum # PNc0054.

Length: 204 ft.

Beam: 41 ft.

Draft: 15.9 ft.

Machinery: 3 screws, two vertical direct-acting engines powered by one flue-tubular boiler

Compliment: 145 officers and crew

Speed: 7 knots

Tonnage: 1,006 tons[13]

‘God-Forsaken Ship’

While Atlanta looked like most other Confederate screw casemate ironclads, there were some critical differences. The ship had an iron hull and Scottish-built engines constructed in 1860. Accordingly, Atlanta had probably the best power plant of any Confederate ironclad. Nevertheless, the ship had several serious problems. It was an ersatz vessel and had serious problems which weakened its operational abilities. There was no air ventilation into the hull, especially the engine room, resulting in extreme heat and foul air. The Atlanta leaked very badly. “It was almost intolerable aboard the Atlanta, there being no method of ventilation, and the heat was intense.”

Midshipman Dabney Scales added: “What a comfortless, infernal and God-forsaken ship.” [14] When the ironclad’s bunkers were filled with coal, it increased the ship’s draft, and water seeped in so that the wardroom and berth deck were covered with nearly a foot of water. Scales further noted that the “officers quarters are the most uncomfortable that I have ever seen. There are no staterooms…the apartments are partitioned off with coarse…dirty canvas…the only thing on board that we can call our own is a pair of hammock hooks, and a mess table.” [15]

Shake-Down Cruise

On July 31, 1862, the ironclad went on its sea trials under the command of Lieutenant Charles H. Blair. The ironclad was slow, making only 7 knots and difficult to steer. The Atlanta leaked badly. Most of the leaks were repaired; nevertheless, inside the hull, the moisture made it almost impossible to withstand the extreme humidity and heat.[16]

Enter Georgia’s Naval Hero

The Atlanta was commissioned on November 23, 1862, and named Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall’s Savannah Squadron’s flagship. Tattnall was the son of a governor of Georgia and later a US senator from Georgia. Josiah joined the navy as a midshipman in 1812 at age 15 and was assigned to USF Constellation. He fought with distinction during the battles of Craney Island and Bladensburg.

Tattnall served during the Second Barbary War and as commander of USS Spitfire during the Mexican War. Eventually, he became commander of the East India Squadron, where he violated US neutrality during the Battle of Taku Forts in the Pei Ho River in support of British and French ships during the Second Opium War.

Tattnall coined the saying, ‘Blood is thicker than water,’ to justify his actions. When the War of the Rebellion began, he joined the Confederate navy and attempted to use his gunboats to thwart Rear Admiral S.P. DuPont’s squadron during the Battle of Port Royal Sound. He was then named as the third commander of CSS Virginia and scuttled the ironclad when Norfolk, Virginia, was captured by Union forces.[17]

Savannah Squadron Commander

After being cleared by a court of inquiry following the destruction of CSS Virginia, Tattnall returned to Savannah, where he assumed command of naval forces defending Savannah. He was determined to place Atlanta into active service. The flag officer wanted to strike at the Federals’ wooden blockaders before the new class of monitors, Passiac-class, arrived at Port Royal Sound and thence into the sounds below Savannah.

“I consider the Atlanta no match for the monitor class of vessel at close quarters, and in shoal waters particularly, as owing to the necessity of lightening her in order…to cross the flats and operate in the Sounds, at least two feet of her hull below the knuckle were exposed with but two inches of iron.” [18] Based on his command of CSS Virginia and knowledge of all of Atlanta’s weaknesses, Tattnall was hesitant to strike against monitors. Nevertheless, he knew that an attempt had to be made.

The New Monitors

Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont, commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, recognized that Atlanta would soon sortie and stationed two monitors, USS Montauk and Passaic, in Ossabaw Sound to guard against any Confederate attack. The admiral, who was already planning his assault against Charleston, South Carolina, also wished for Montauk, commanded by Commander John Lorimer Worden, to test its powers against Fort McAllister on the Big Ogeechee River. Worden was also to damage the former commerce raider Nashville (now Rattlesnake) and the railroad bridge over the Big Ogeechee. Only Nashville was destroyed.[19]

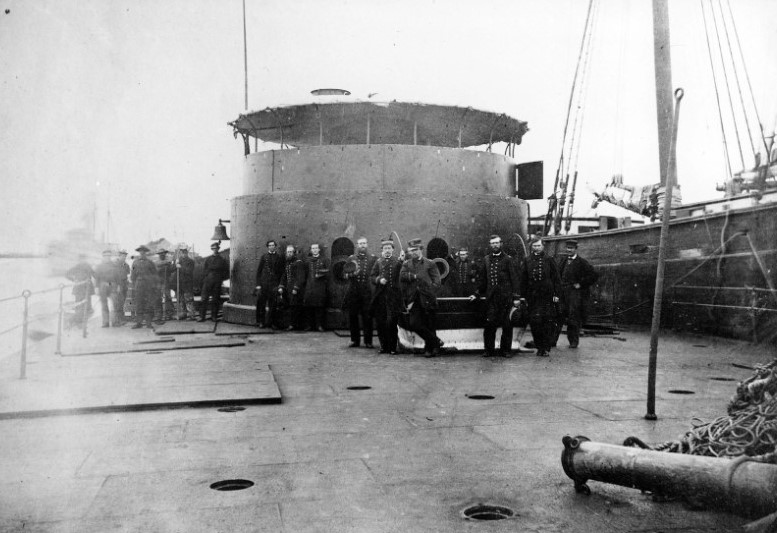

The new monitors that concerned Tattnall were those of the Passiac-class. The USS Monitor’s success blocking CSS Virginia from destroying more Union wooden ships on March 9, 1862, resulted in a new contract for John Ericsson to build another 10 monitor-styled warships known as Passaic-class. Ericsson recognized some of Monitor’s flaws and sought to correct them with this new class. The ships had the pilothouse located on top of the turret to allow greater vision and communication with the pilot, captain, and crew. These vessels were almost longer than the original design and had a less pronounced overhang with an additional 15 inches of freeboard. The Passaic-class also featured an 18-foot tall funnel and improved ventilation. [20]

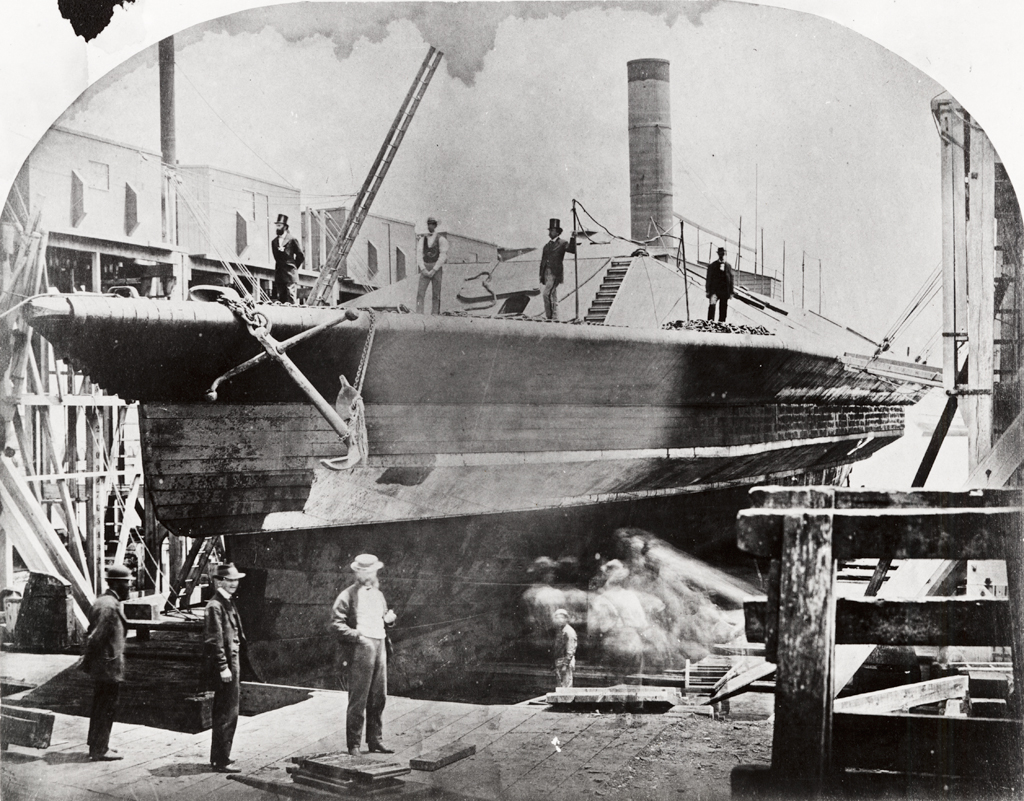

and date unknown. Courtesy of The New York Public Library, # G90F310_055F.

Perhaps the most important improvement was adding one XV-inch Dahlgren shell gun to these ironclads’ battery. This gun was so large that the muzzle could not project out of the gunport and was mounted flush. There were 34 versions of these guns made at Fort Pitt Arsenal, and they were called Short or Passaic versions as the barrel was only 162 inches long. This required a smokebox to be installed inside the turret to capture the escaping gases and smoke. These larger Dahlgrens, weighing 42,000 lbs., had the hitting power to break through Confederate casemate ironclads as they could hurl a 440 lb. solid shot 2,100 yds. [21]

USS Weehawken Characteristics

Builder: Secor, Jersey City, New Jersey

Commissioned: January 18, 1863

Tonnage: 1,335

Machinery: 1 screw, Ericsson vibrating lever (trunk) engine

Compliment: 67-88 officers and crew

Armament: one XV-inch shell gun and one XI-inch shell gun

Speed: 7 knots

Armor: 11 inches turret, 5 inches sides, one inch deck, 8 inches pilothouse.[22]

Tattnall’s Attempts To Strike

Tattnall believed that his best course of action was to strike against the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron’s Port Royal Sound base when DuPont’s monitors were elsewhere. His first attempt to enter Wassaw Sound was frustrated on January 5, 1863, as CS Army engineers had not cleared the Savannah River obstructions.

The citizens of Savannah clamored for action. The Atlanta moved downriver again on February 3, 1863. Even though the obstructions were cleared, a heavy gale forced water away from the obstructions, which meant that Atlanta could not pass. Dabney Scales noted: “So we were once again disappointed and fear that we will be unable to get out this spring tide….of course we will be branded as cowards by the unthinking portion of the citizens of Savannah.” [23]

Tattnall’s Last Attempt

Finally, on March 19, Tattnall took the ironclad through the obstructions. According to intelligence received by the flag officer, the monitors that had once been in Ossabaw and Wassaw sounds had all returned to Port Royal Sound in preparation for DuPont’s ironclad attack on Charleston harbor. Tattnall was convinced that Union station was key to the South Atlantic Blocking Squadron’s ability to maintain its blockade. When Atlanta reached the mouth of the Wilmington River, Tattnall waited for high tide to enter Wassaw Sound. Unfortunately, a small picket boat from CSS Georgia was taken over by two disgruntled Irish conscripts who had taken a revolver from the officer’s coat. They rowed the boat to Union-controlled Fort Pulaski and told the Federals all about Tattnall’s plan that they had overheard from officers. Tattnall had to call off his sorte, and three monitors were returned to Port Royal. [24]

The Replacements

Even though Tattnall’s plan was excellent and could have possibly done great damage to the Union’s Port Royal Sound base, Secretary Mallory lost faith in Tattnall and replaced him with Captain Richard Lucien Page. Page had joined the US Navy as a midshipman in 1824, and he served for the next 37 years. He was aboard USS Brandywine when that frigate took the Marquis De Lafayette back to France after his American tour in 1825. He was an ordnance officer, and then executive officer of the Gosport Navy Yard just before Virginia left the Union. He served in several capacities in the Confederate Navy, including building batteries to defend Hampton Roads. He was assigned to create the Charlotte (NC) Navy Yard in 1862. He was then assigned to command the then under-construction CSS Savannah and promoted Captain. Page was a good friend of Josiah Tattnall’s and only served as commander of the Savannah Squadron for less than a month when Captain William Webb replaced him. Page, who resembled his first cousin Robert E. Lee, resigned from the CS Navy and became a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. Page commanded Fort Morgan during the Battle of Mobile Bay. [25]

Secretary Mallory wanted younger, more aggressive naval officers to command the Confederacy’s ironclads. The secretary had created a ‘Retirement Board’ to weed out those older US Navy officers deemed incapable or unworthy of their rank. They were then placed on the retirement list. Mallory authorized this board as chairman of the US Senate Committee on the Conduct of Naval Affairs. [26] Mallory set out to do the same for the CS Navy by creating a ‘Provisional Confederate Navy,’ which enabled Mallory to bypass promotion based on seniority. [27]

Enter Webb

One of these officers was Commander William Augusta Webb. Webb joined the U.S. Navy at age 14 in 1838. He served during the Mexican War aboard the storeship USS Southampton. Webb resigned his commission when Virginia left the Union and joined the Confederate Navy. He eventually became captain of the CSS Teaser in the James River Squadron, commanded by his brother-in-law Captain John Randolph Tucker. On March 8, 1862, Webb served with great distinction and aggressiveness when he rescued Lieutenant John Dabney Minor and his cutter’s crew from Union fire from Camp Butler on Newport News Point during the surrender of the USS Congress.

Webb would be assigned to the Charleston Squadron until transferred to command the Savannah Squadron. Lieutenant George T. Sinclair had temporarily commanded before Webb arrived in Atlanta; yet, he requested a transfer immediately. He wrote: “nothing would induce me to leave here so long as there is the slightest prospect of a fight, which by the way, I now think is very remote, more probably never.” [28]

Young and Reckless

While many believe that Webb was a “very reckless young officer,” many also perceived that he would “at once do something. Another officer noted that Webb “had orders to assume offensive action against the enemy… He was specially promoted to give him rank enough to assume his new position. Webb accordingly came down here very much elated at his advancement. He was boastful and disinclined to listen to the counsel of older and wiser heads.”[29]

Webb’s Intent

Webb advised Mallory that he intended to strike at the Union fleet as soon as feasible. He attempted an attack in May 1863; yet, Atlanta’s forward engine broke down, and the deep draft ironclad ran aground. The engine was repaired, and Webb indicated that he planned to use the next full tide to strike at the enemy. Mallory, in turn, told Webb not to sortie until CSS Savannah was ready to join the attack. The ram Savannah was a Richmond-class casemate ironclad built by H.F. Willink and armed with four Brooke rifles. The Savannah would eventually be commissioned on June 30, 1863. Mallory’s orders were very sound.

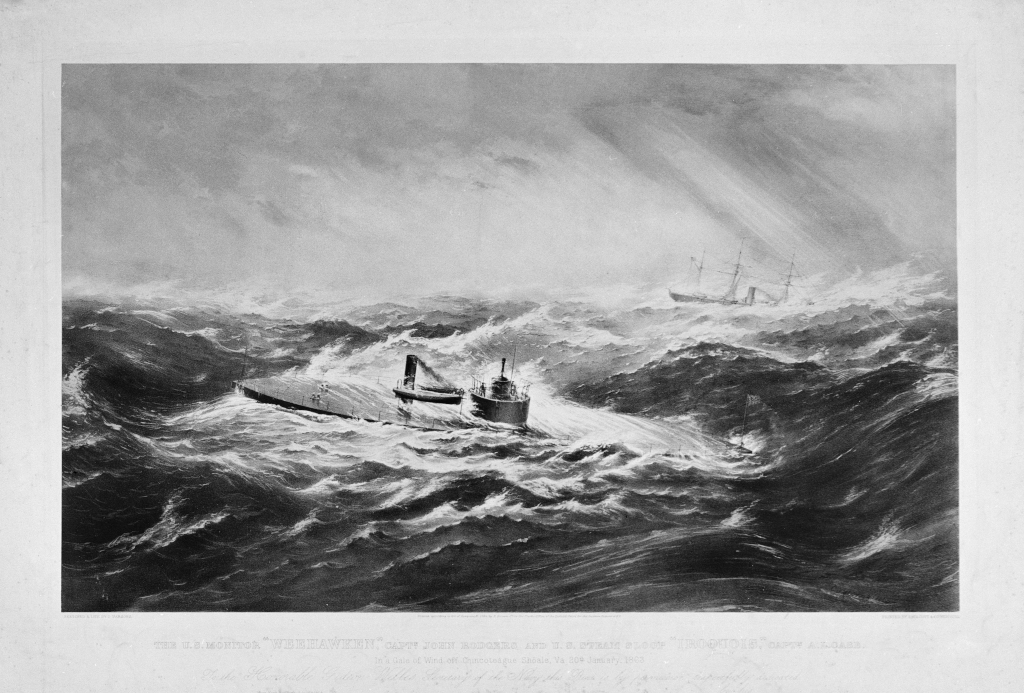

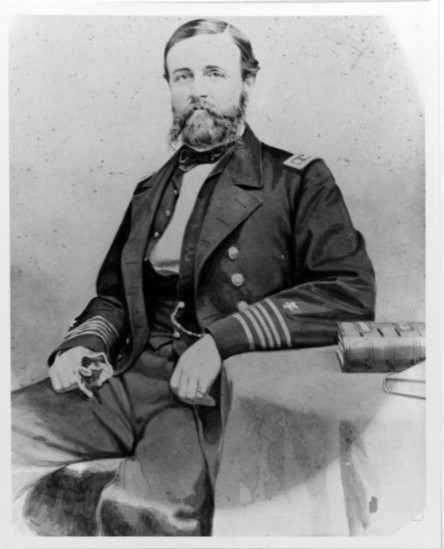

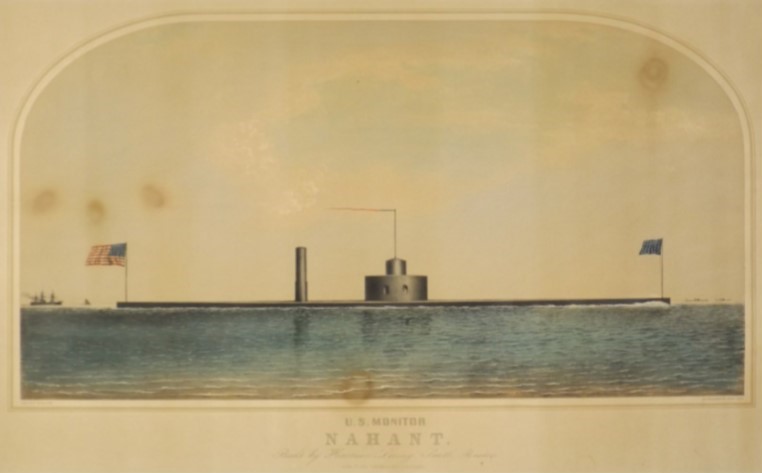

Nevertheless, Webb disobeyed Mallory’s orders to wait for the other ironclad. Webb was intent on raising the blockade, attacking Port Royal, and besieging Fort Pulaski. Before he could launch his attack, however, DuPont learned about the impending Atlanta strike. So he ordered two monitors, USS Weehawken, captained by Commander John Rogers, and the USS Nahant, commanded by Commander John Downes, to block Wassaw Sound.[30] Webb appeared not to care about the monitors. The Atlanta’s commander intended to destroy one monitor with his spar torpedo and capture the other mother with his battery. [31]

Preparing the Attack

On the evening of June 15, 1863, Webb steamed Atlanta across the obstructions and then coaled his ship. The next evening, he placed his ship near the entrance to the sound about five to six miles away from the monitors. At 3:30 a.m. June 17, Atlanta got underway as Webb hoped to surprise the Federal ships. Two wooden gunboats, CSS Isondiga and CSS Resolute, followed the ironclad. Webb believed that he would need them to tow one or both monitors back to Savannah.[32]

Stranded

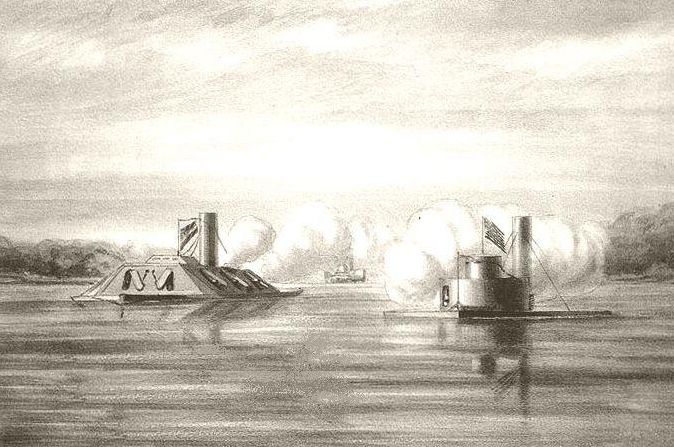

The Weehawken noticed Atlanta’s approach at 4:10 a.m. The Rebel ram approached the Union ships at full speed to within 1.5 miles and fired its first shot at Weehawken, which passed over that monitor and struck near Nahant. Suddenly, Atlanta stopped! The deep draft ironclad ran aground.

Webb reported, “I immediately informed the pilots of the fact and ordered the engines to be backed, but it was fully fifteen minutes before she was in motion, though the tide was rising fast. As soon as the ship was well afloat, I ordered the engines to go ahead, with the hope of turning her more into the channel, but she could not obey her helm, from the fact of the flood tide being on her starboard bow, and her bottom so near the ground. She was consequently forced upon the bank again.” Webb noted that Weehawken was steaming toward the Confederate ironclad and ordered Lieutenant Barbot to fire at the Union ironclad to stop its advance using the forward Brooke rifle. Nothing, however, would stop Rodgers from maintaining his course toward the stranded Confederate ironclad.[33]

Unequal Odds

John Rodgers realized that Atlanta must be aground and moved his ship to within 200 to 300 yards of Atlanta. Then Rodgers fired both guns simultaneously. The XI-inch shot passed over the Confederate ironclad; however, the XV-inch shot slammed into Atlanta’s casemate just above the port shutter, “nearly abreast the pilothouse, driving the armor through, tearing away the woodwork inside 3 feet wide by the entire length of shield, causing the solid shot in the racks and everything movable in the vicinity to be hurled across the deck with such force as to knock down, wound, and disable the entire gun’s crew of the port broadside gun in charge of Lieutenant Thurston, CSMC and also half of the Lieutenant Barbot’s bow gun, some thirty men being injured more or less.” While the 440 lb. shot did not penetrate, its impact was devastating and, due to the tilt of the grounding, Webb could not respond with his own Brooke guns.

From Weehawken’s XI-inch Dahlgren, the next shot struck Atlanta’s knuckle; however, it did no damage other than starting a leak. The knuckle was only protected by two inches of iron plate, proving the theory that the XV-inch Dalhgrens were needed to break through Confederate casemates.

The next two shots came from Weehawken’S XV-inch shell guns. One struck the starboard side port shutter of Master Wragg’s gun just as it had been loaded. It broke the shutter in half, tearing up the iron plate and sending iron and wooden fragments inside, wounding half of the gun crew. The final shot hit the port corner of the pilothouse chopping the top off and wounding two pilots.[34]

Surrender

Webb considered his options as Nahant moved onto the other quarter of Atlanta. With Weehawken on the other, the Confederate ironclad was in trouble as it would be pounded to pieces by both monitors’ heavy shell guns. Obviously, the 4-inch shield could not stop the XV-inch shot. The ironclad was still aground, and the tide would not be at flood for another 90 minutes. The small gunports limited Atlanta’s field of fire, so the Confederate ship could not effectively return fire. Sadly, Webb, to save the greater effusion of blood, had no choice but to surrender. The Atlanta’s casualties were one killed and 16 wounded, requiring hospitalization. Many others were concussed. [35] As James Bulloch noted, it “could hardly be said that he was fighting his ship—he was simply enduring the fire of his adversary.” [36]

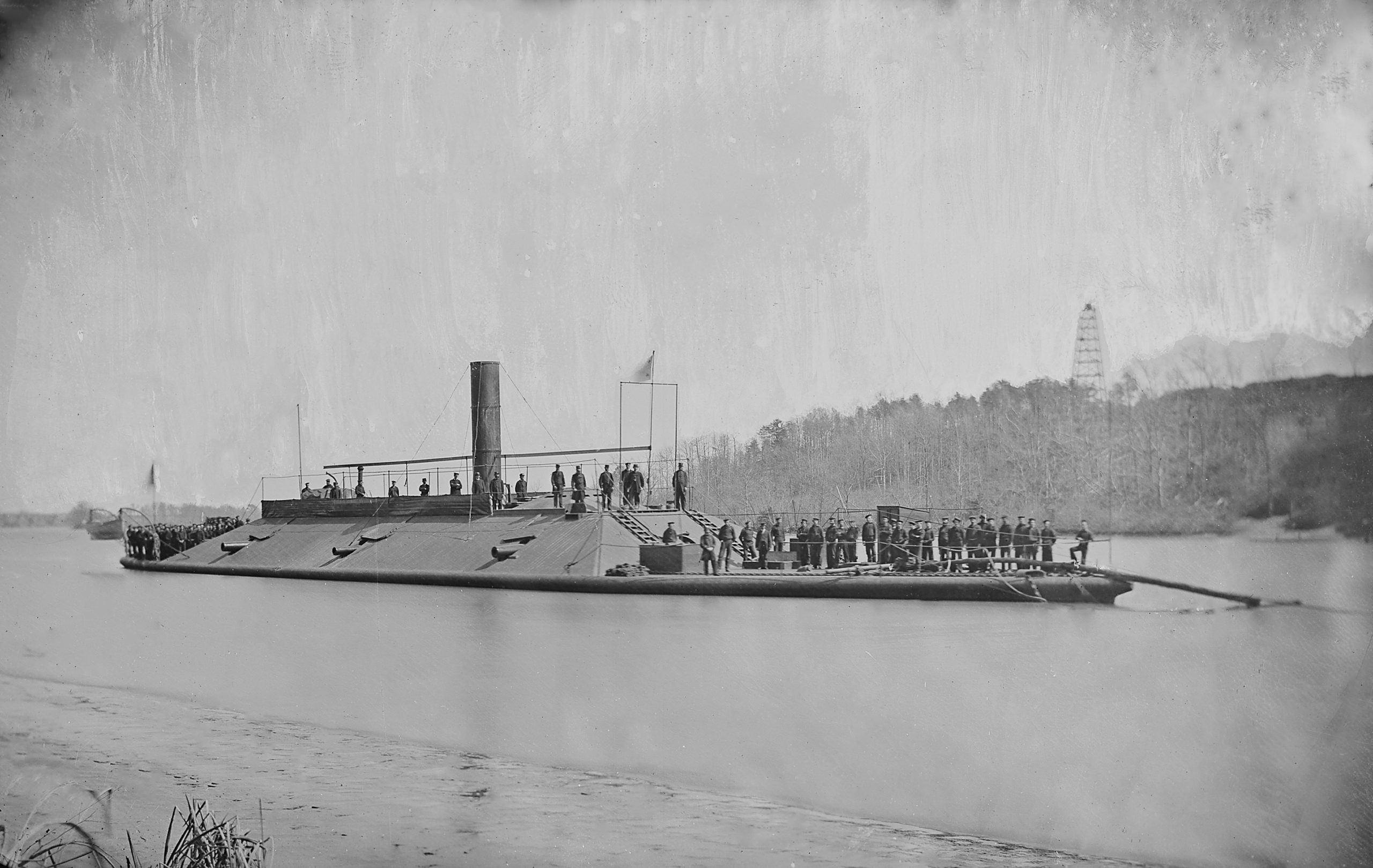

USS Atlanta

The Atlanta was easily pulled off the shoal and reached Port Royal Sound under its own power. Temporary repairs were conducted. The crews of Weehawken, Nahant, and the wooden gunboat USS Cimarron shared the prize money totaling $350,000. Then the ironclad steamed to the Washington Navy yard for further repairs. The ship’s armament was switched to two 150-pounder Parrott rifles in bow and stern in pivot and two 100-pounder Parrott rifles amidships.

The Atlanta was assigned to the James River Flotilla, North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. The ironclad’s new duty was to guard against any assault by the Confederate James River Squadron. Along with the wooden gunboat USS Dawn, the Atlanta helped repulse a cavalry attack led by Major General Fitzhugh Lee against US Colored Troops defending Fort Powhatan. The vessel was decommissioned in Philadelphia and placed in ordinary. [37]

Triumfo

Civil unrest in Haiti was rampant during the mid-19th century. In 1867 General Sylvain Salnave overthrew the existing government and installed himself as president for life. A revolution against Salnave’s rule arose soon after he assumed power. To support his government, Salnave purchased USS Atlanta for $250,000, renaming it Triumfo (Triumph). The ship departed Philadelphia on December 16, 1869, and disappeared somewhere between the Delaware capes and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. [38]

Afterword

The CSS Atlanta was a problematic ironclad. It was one of two Confederate ironclads ‘captured live’ by the Federals. Even though it had an iron hull with excellent engines, its conversion was poorly completed by Asa and Nelson Tift. The Tifts were not true shipbuilders; they were businessmen who convinced Mallory that they could build casemate ironclads. Sadly, they really could not build good ones. The CSS Mississippi had an overly complex engine system and other issues that resulted in the Mississippi‘s premature destruction. The Atlanta’s design made it a difficult warship to operate, especially in the shallow confines of the rivers and sounds below Savannah. The ironclad simply had too great of a draft, which made it hard to manage its helm. There was no ventilation system, so it was unbearable to work beneath decks, and its gunports did not allow an adequate field of fire.

Both Tattnall and Page realized Atlanta’s limitations, especially when fighting monitors. Webb was overconfident and reckless in his decision to attack Weehawken and Nahant. Nevertheless, Webb “was confident of success, as I felt confidence in my torpedo, which I knew would do its work to my satisfaction.” [39] This tactic may have worked in a fight with one monitor; yet, Webb was just too foolhardy to attempt to engage two of them. He should have waited for CSS Savannah to be available, as Mallory had advised. However, even with the support of, Savannah, it would have been a difficult fight. The power of XV-inch 440 lb. shot was just too much for any Confederate ironclad to withstand.

Endnotes

- William C. Emmerson. “Unfounded Hopes: A Design Analysis of the Confederate Steamer CSS Atlanta.” Warship International. Toledo, Ohio: International Naval Research Organization. XXXZIII(4): 367-387, 1995.

- Bulloch, James D., The Secret Service Of The Confederate States In Europe Or, How The Confederate Cruisers Were Equipped. New York: G.P. Putnam, 1884, vol.1, p.109.

- Anderson, Edward Clifford, Afloat and Ashore: The Confederate Diary of Colonel Edward Clifford Anderson, University of Alabama Press, 1977, p.10-71. And Smith, Derek, Civil War Savannah, Frederic C. Bell, 1997, p.37.

- Bulloch, 110-115

- J. Thomas Scharf, History Of The Confederate Navy, New York: Gramercy Books, 1996, 638-640.

- IBID.

- Bulloch, 151.

- Scharf, 640-641.

- Charles C. Jones, Jr.,The Life And Services Of Commodore Josiah Tattnall, Savannah: Morning News Steam Printing House, 1878, 223.

- Emerson, 373.

- Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Navies In The War Of The Rebellion. (Hereinafter referred to ORN), ser 1, vol 14, 273-274

- IBID, 274-275.

- Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies, 1855-1883, Annapolis MD: 153.

- Emerson, 373

- William N. Still, Jr., Iron Afloat: The Story Of The Confederate Armorclads, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1985, 129-130

- Emerson, 377.

- Patricia L. Faust, ed., Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Civil War, New York: Harper & Row, 1986, 742.

- Jones, 224.

- Samuel T.Browne, ‘First Cruise of the Montauk,” Rodman Post, No. 12, Department of Rhode Island, Grand Army of the Republic, Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society of Rhode Island, Providence, RI: The N. Bangs Williams Co., 1880, 30-31.

- Silverstone, 5.

- Edwin Olmstead; Wayne E. Stark; Spencer C. Tucker, The Big Guns: Civil War Siege, Seacoast, And Naval Cannon, Alexandria Bay, New York: Museum Restoration Service, 1997.

- Silverstone, 5.

- Still, 132.

- Jones, 236.

- Faust, 553.

- Joseph T. Durkin, S.J., Confederate Navy Chief: Stephen R. Mallory, Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. 1987, 70-83.

- Still, 134.

- IBID, 134-135.

- IBID. 135

- ORN, ser. 1, vol. 14, 263.

- IBID. 288

- IBID., 290-291.

- IBID.

- IBID

- IBID, 292

- Bulloch, 147-148

- Emerson, 282, 284; Still, 186, and Silverstone, 153.

- Schiena, Robert L., Latin America, A Naval History, 1810-1987. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987, 39.

- ORN, ser. 1, vol. 14, 291