Changing Perspectives during WWII

As mentioned in some previous blogs, World War II was the first time in US history that women were allowed to officially enter the military in any major capacity, outside of Nursing. This change brought many white, middle-class women into the labor force for the first time and opened up opportunities to women and people of color in jobs that would otherwise be denied to them. The Women’s Army Corps or WAC (originally the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps) was the only one of these groups to integrate women into its corresponding military branch fully. However, in the 1940s, there were much stricter ideas of gender norms, gender expression, and heteronormativity. This meant there was significant pushback against the idea of women joining the military, as this was viewed as the epitome of masculine spaces. As a result, many suggested that women did not belong in the military, despite many women joining the WAC (and other groups) and excelling in their new roles.

The Slander Campaign

There was a lot of concern about what women joining the military might mean. A slander campaign arose between 1943-1944, about 1-2 years after the forming of WAC/WAAC, which claimed that women who joined the WAC were either promiscuous or lesbians. These rumors were sourced from several places. One is a prominent newspaper article on the WACs claiming that WACs would receive free prophylactic equipment, just as the male GIs did. However, this was inherently false, one of the many double standards that women in the military were held to.

Another source of the rumors was actually from male GIs. Many men felt threatened or uncomfortable by the presence of women in the military. The official purpose of the WAC was to “free up a man to fight” by taking over the many support roles in the military. However, for many GIs, this meant that WACs would be taking their relatively safe support role, and the men would be sent to a combat role. This perceived threat from the WAC fed into the slander campaigns against women in the military.

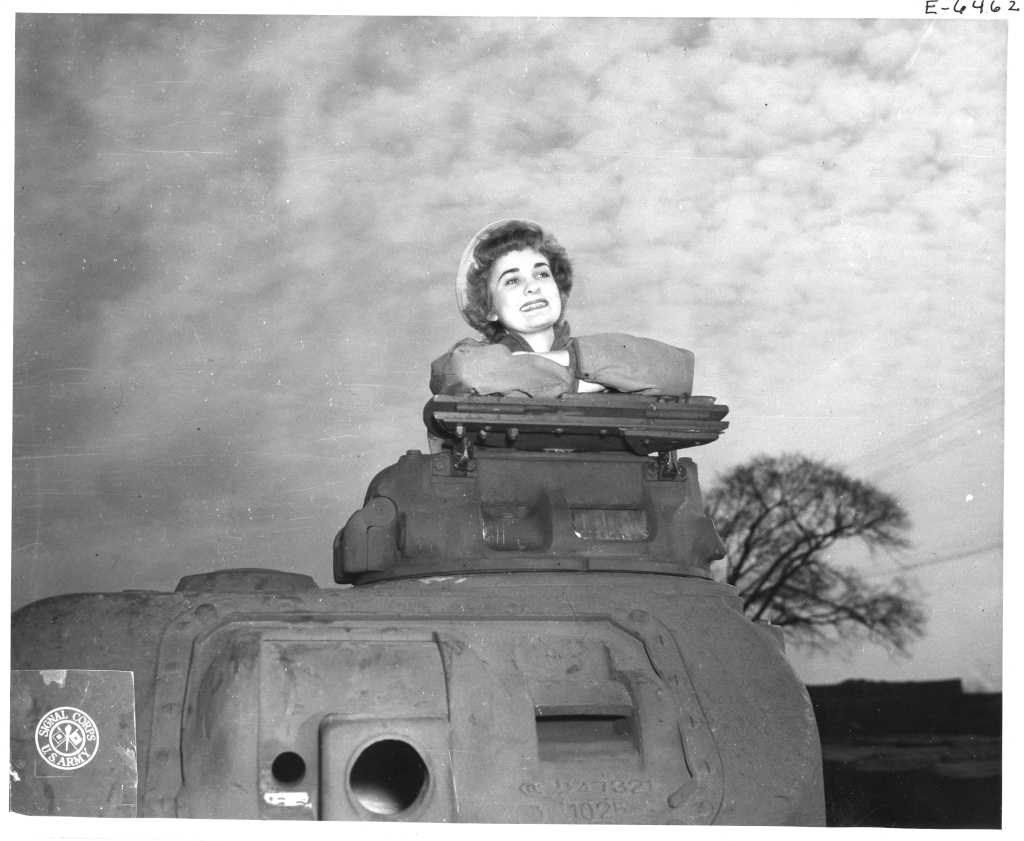

Propaganda and Femininity

To combat the slander campaign, the Director of the WAC, Oveta Culp Hobby, created propaganda with an ideal image of the WAC, calling for women to maintain their ‘femininity’ while in the military. One of the reasons we have photographs of WACs at The Mariners’ Museum and Colonial Williamsburg is this anti-slander campaign. These were propaganda images used to promote the idea of WACs being feminine, wholesome women who went to museums, not ‘loose women’ who went out drinking. There were also many others outside of the military who worked to support the WACs against the slander campaign, including Representative Edith Rogers who told Congress that “nothing would please Hitler more” than to discredit WACs and American women.

In addition to this wholesome propaganda for the WAC, the military had written legislation against homosexuality among service men and women. Despite this, many lesbians (and other LGBTQ+ service members) created their own space within the WAC. Although homosexuality was prohibited in the military, when it came to the WACs, higher-ups were more worried about the ‘appearance’ of lesbians in the WAC than their actual presence. The military did provide regulations for the “undesirable discharge of homosexuals,” but there was concern that if many WACs were discharged in this way, it would only add fuel to the slander campaign. Thus, officers were told to only consider undesirable discharge in the most extreme cases.

LGBTQ+ Women in the WAC

Because of this, many LGBTQ+ women were able to find their own place in the WAC, and develop their own culture within the military. Several veterans recounted having coded language to find other queer women and having more freedom in the WAC to express themselves in a less feminine way, if they so chose. Some veterans talked about joining the WAC to be with other women, while others discovered their sexuality after joining the WAC. Sentiment might vary between bases and units, as both straight and LGBTQ+ veterans from some bases said that “no one really cared” while others remembered paranoia and distrust surrounding the idea of homosexuality. Overall, because anti-homosexual legislation did exist, it was still a precarious existence for LGBTQ+ service members. After the war ended, and there was less need for an “all hands” mentality towards ending the war, efforts to remove lesbians and LGBTQ+ members of the armed forces increased.

One WAC in particular, Sgt Johnnie Phelps, talked about her experience as a lesbian in the WAC during WWII on several occasions. She joined the WACs initially out of patriotism, and once in the service, realized she was attracted to women. “The thing I felt most was the fact that I was doing something for my country. When I tell you that I was patriotic then, I was patriotic. Of course, I’m also patriotic today. Gay I may be.”

Phelps initially served as a WAC medic in the south pacific and was able to find a small community of LGBTQ+ women there. She received a purple heart for her service and earned enough points to go home, but the war was still on, so she re-enlisted to go to Europe. However, by the time she got there, the war was over, and she served as part of the Army of Occupation. Phelps was stationed at Frankfurt, as the European Motor Sergeant, under the direct command of General Dwight. D. Eisenhower.

At this time, General Eisenhower received a report of a lesbian presence in the battalion in which Phelps Served, and was given orders to remove them. “The General called me in and gave me a direct order. ‘It’s been reported to me that there are lesbians in the WAC battalion. I want you to find them and give me a list. We’ve got to get rid of them.’ I said ‘Sir, if the General pleases, I’ll be happy to check into this and make you a list. But you’ve got to know, when you get the list back, my name’s going to be the first.’…His secretary at the time was standing right next to me. She just looked at him, and she said ‘Sir, if the General pleases, Sergeant Phelps will have to be second on the list, because mine will be first. You see, I’m going to type it.’ He sat back in his chair, looked at us, and then I said, ‘Sir, if the General pleases, there are some things I’d like to point out to you. You have the highest ranking WAC battalion assembled anywhere in the world. Most decorated. If you want to get rid of your file clerks, typists, section commanders, and your most key personnel, then I’ll make that list….If you want me to get rid of these women, I’ll get rid of them, but I’ll go with them.’ He just looked at me and said “Forget that order. Forget about it.”

“That was the last we ever heard of it. There were almost nine hundred women in that battalion. I could honestly say that 95 percent of them were lesbians.” It is thanks to Phelps and her strong stance against removing LGBTQ+ members from her WAC battalion that their base did not go through ‘lesbian witch-hunts’ as many other bases did, after the war.

LGBTQ+ Community in HRPE

While we don’t know if any of the WACs featured in the Museum images from Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation (HRPE) would consider themselves part of the LGBTQ+ community, statistically we know that many of the WACs, GIs, Nurses, and other service members who worked at and passed through HRPE were LGBTQ+. These women fought not only sexism, but homophobia, and heteronormative ideas about gender and gender expression, all to carve out a place for themselves within the US military. They proved that not only could women be part of the military, but they could at once be patriots and part of the LGBTQ+ community.

References and Further Reading:

Creating GI Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women’s Army Corps During World War II by Leisa D. Meyer

My Country, My Right to Serve: Experiences of Gay Men and Women in the Military, World War II to the Present by Mary Ann Humphrey

Women, Gender and World War II by Mellisa A. McEuen

Coming out Under Fire: The Story of Gay and Lesbian Service Members

“Dykes” or “Whores”: Sexuality and the Women’s Army Corps in the United States during World War II by Michaela Hampf