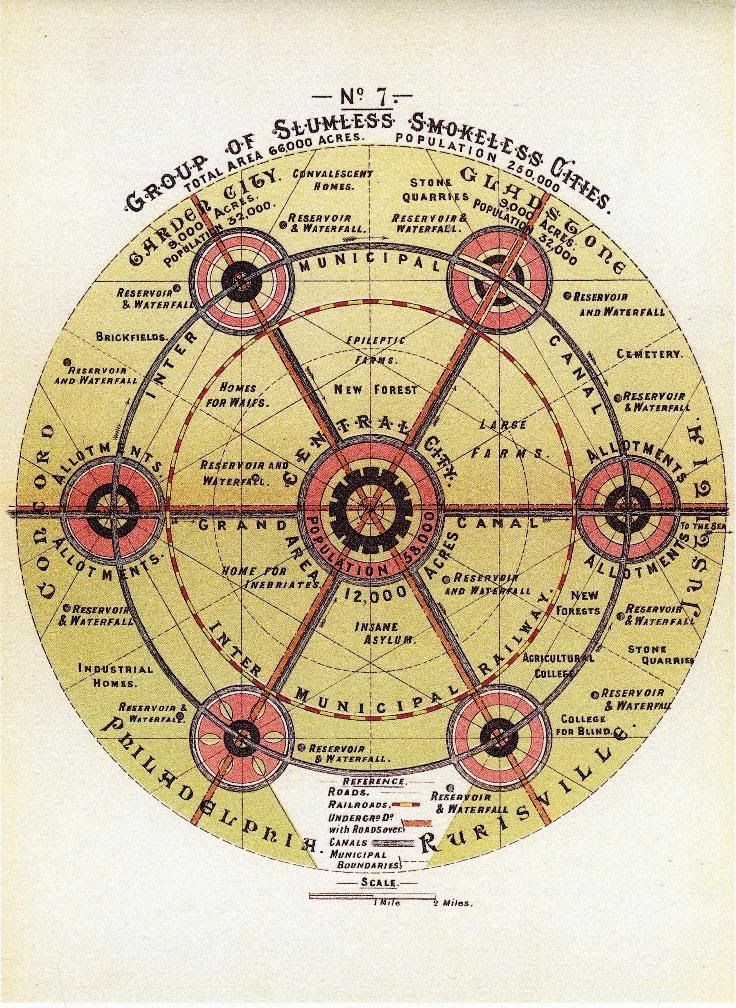

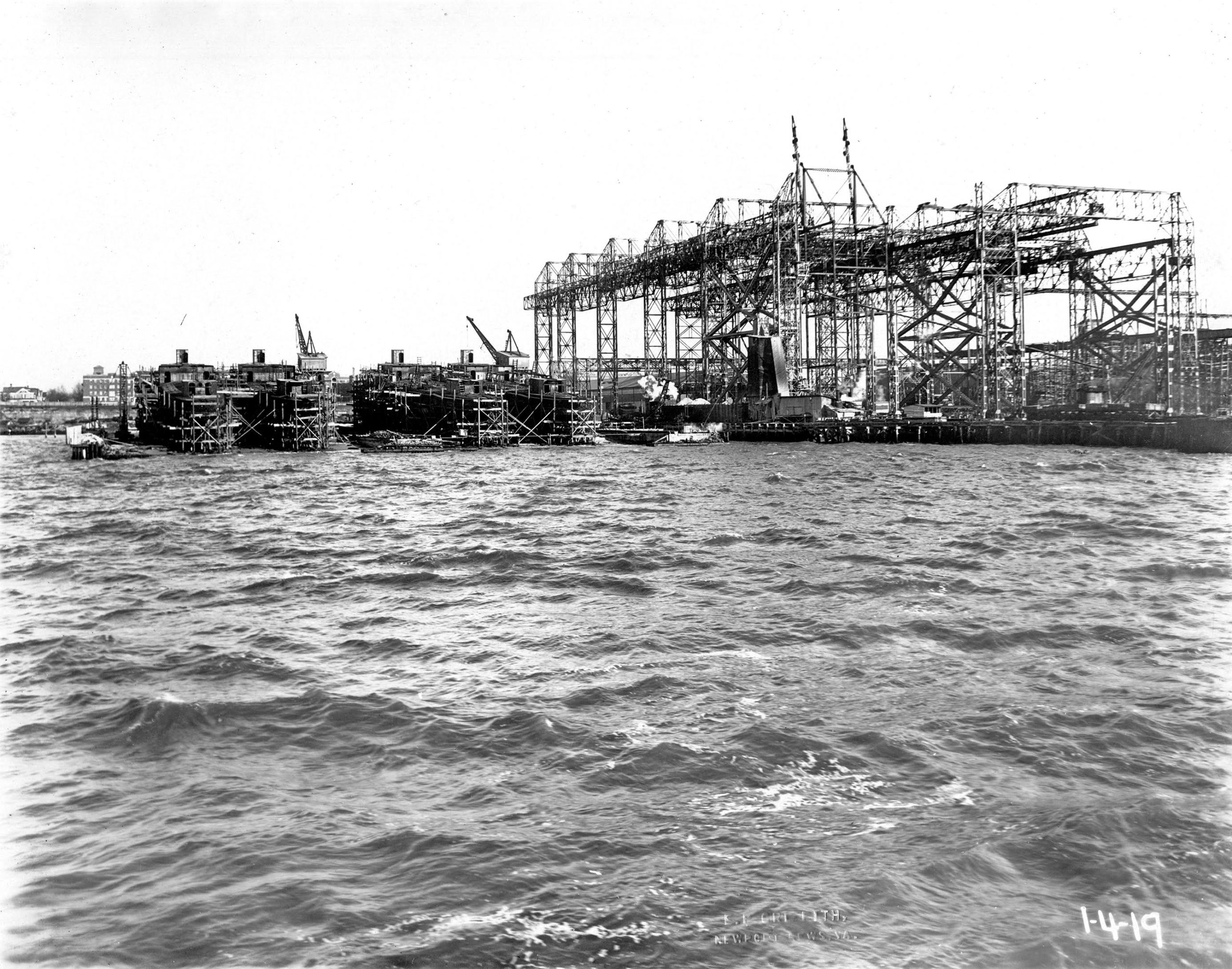

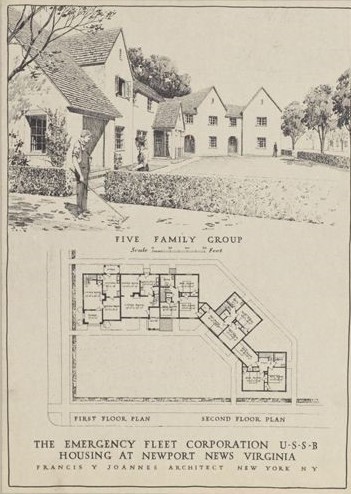

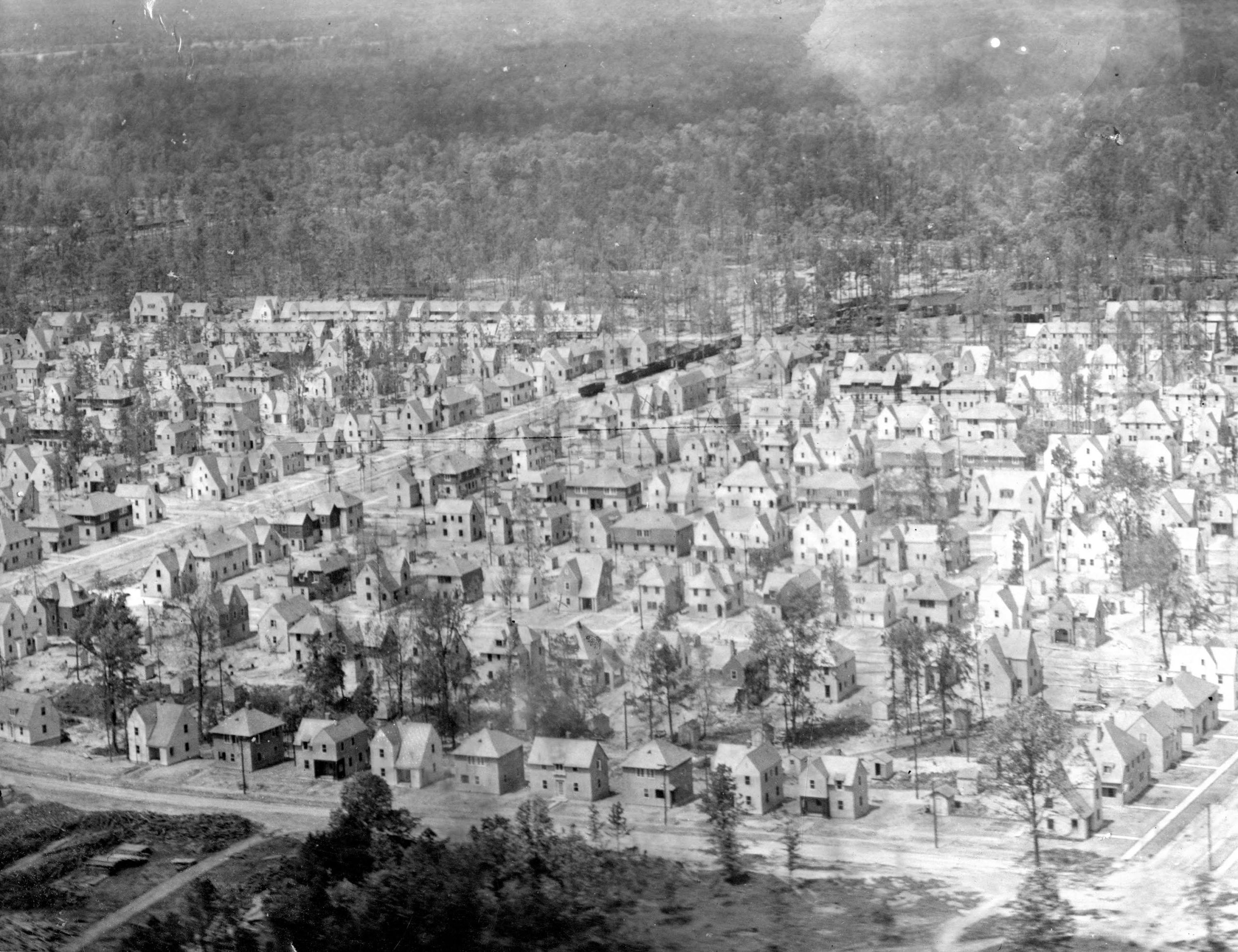

The Washington Naval Treaty’s impact on the Newport News Shipyard was devastating. Several major naval construction contracts were canceled, and the yard’s workforce dropped from 14,000 to 2,200. This had a significant impact on the new Garden City movement community Hilton Village. Newport News Shipyard Chairman of the Board Henry Edwards Huntington had a particular interest in Hilton Village. He purchased the entire village from the US Shipping Board and offered individual houses for sale by single buyers. He completed a variety of improvements; yet, only 240 homes were occupied in 1924.

Eddie Steps In

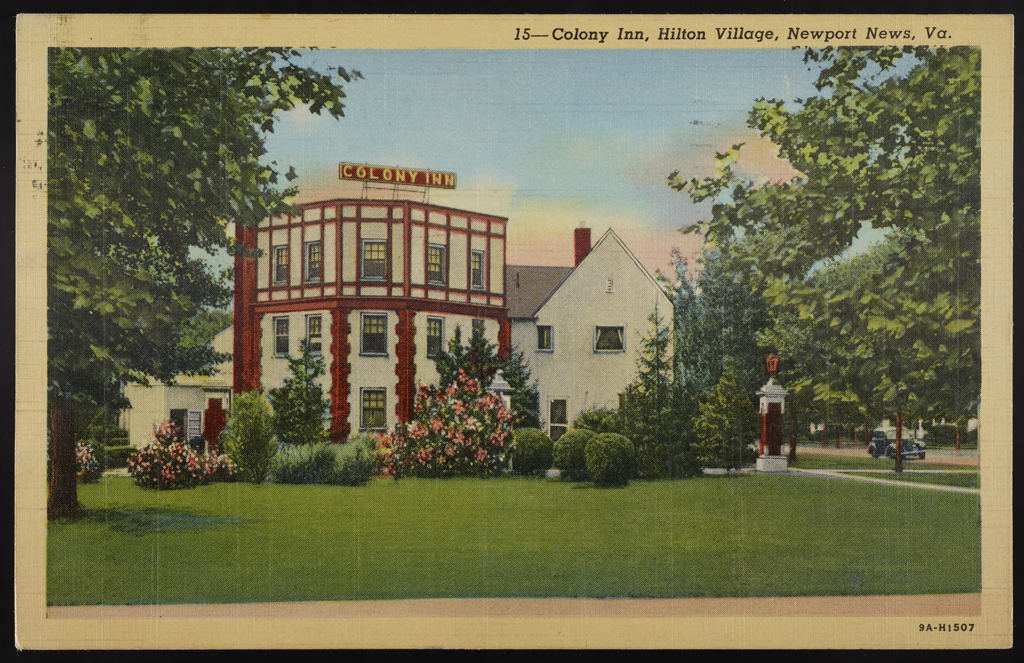

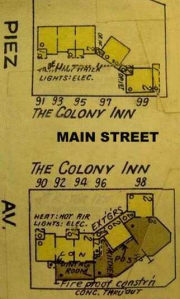

Henry “‘Eddie”’ Huntington decided to use his Newport News Realty Company to revitalize Hilton and construct the Colony Inn. The inn was built at the intersection of Warwick Road and Main Street. It replaced a 1918 officers’ club serving Camp Hill and Camp Morrison and incorporated 10 existing Hilton houses, five on each side of the road. J. Philip Keisecker, manager of the shipyard’s real estate office, had suggested to Eddie Huntington that an inn be established in Hilton Village. Kiesecker believed an inn would offer a quaint and inviting respite for travelers “that would also establish good public relations between the Shipyard and the community.”

Huntington agreed and provided his enthusiastic support for Kiesecker’s dream “to impress people that the shipyard was willing to spend some money locally” and give an attractive stopping place for visitors to the Peninsula.

Construction

The Colony Inn was built in two sections. The south portion — three row houses (90,92, and 94 Main Street) and two single homes (96 and 98 Main Street) — were linked together. Original plans called for an eight-story tower with a roof garden. The tower was not built as planned and stopped at the third story. Also abandoned were the roof garden and proposed swimming pool. The old English-styled exterior was matched with an “equally charming interior,” noted the Times-Herald.

“The main building itself is furnished throughout with the lobbies, large room, and office on each side of the entrance. The south section featured seventeen guest rooms.

Across Main Street were additional accommodations of 18 rooms using the buildings numbered 91, 93, 95, 97, and 99 Main Street. A gas station and metal garages for guests’ cars were in the rear. The acquisition costs for the Colony Inn totaled $80,000.

Authentic Architecture, Fine Furnishings

Promoted as “An English Inn on the American Plan,” the Colony Inn’s charming Tudor Revival architecture was enhanced by its interior decor. Most public rooms’ furnishings came from converting the SS Leviathan from a troopship to a passenger liner. The ornate German woodwork and furniture removed from the former Vaterland were placed in the Inn. The dining room, divided into three rooms, occupied space on the main building’s first floor.

One of these rooms was a sun parlor with high, broad windows. At one end of the main dining section was a large decorative map of the Virginia Peninsula by Thomas C. Skinner, similar to the paintings he produced for The Chamberlin on Old Point Comfort in Hampton. An “old English spirit” gave the Colony Inn a delightful atmosphere. Coupled with “typical Southern hospitality, the Inn never suffered from a lack of patronage even during the darkest days of the Depression.”

Olde English Elegance

The Colony Inn was a posh hotel, and several Hilton residents declared that they had seen many Rolls-Royces pull up to the entrance. June Waters, then a fifth-grader at Hilton Elementary, walked every afternoon from school to the Inn for her piano lessons from Mrs. Elsie King. A butler in a white coat admitted her escorting her to the baby grand piano in the formal dining room. As she strode over the slate floors, she passed by the “impeccably set tables with pressed white cloths as she awaited her lessons.” She declared that she “felt like a princess.”

The American Plan

The Inn’s rate for a single room without a bath was $1.50 a night, while a room with a bath was rented for $3.50. In each building, the Daily Press reported, “are attractive suites, with sitting rooms, bedrooms, and bath. The Inn has 35 rooms in all.” The guest rooms in both buildings were attractively grouped in twos. Each of the Inn’s rooms is an outside room with plenty of windows and is well ventilated. Many of the rooms have connecting baths. Each room has a telephone, and those rooms which do not have baths have running water and are convenient to baths that will be used by one or two rooms.”

All the furniture was “specially built for the Inn.” It featured numerous old English designs, “with hand-done benches and fire guards. The wall decorations carry out the English effect and just off the lobby is a replica of an old English tavern bar.” The north section also featured “several club rooms suitable for afternoon teas, card parties, and the like.”

The best accommodation was the Huntington Suite, replete with a king-size bed, custom made for Archer Huntington, who was six feet five inches tall, and his wife, the famous sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington, who was six feet tall. Other luminaries included President and Mrs. Herbert Hoover and three other first ladies–Edith Wilson, Grace Coolidge, and Eleanor Roosevelt–who frequented Newport News to attend launchings at the shipyard, as well as other special events.

Other notable guests at the Inn included Philadelphia industrialist Archibald McCrea and his wife Mollie, who purchased Carter’s Grove Plantation near Williamsburg in 1928. The mansion required extensive restoration, so the McCreas chose the Colony Inn as their home during the renovation process for several years. It is said that when Robert Frost visited the noted artist, J.J. Lankes in Hilton Village, he stayed at the Colony Inn.

The Poshest Place

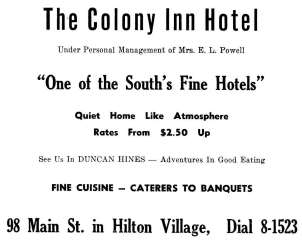

The Colony Inn was well advertised and promoted. Outside of The Chamberlin, it was the “poshest” place to stay on the Peninsula. These were the days before the Williamsburg Inn. When the Yorktown Sesquicentennial was held in 1931, the Colony Inn touted itself as an easy drive on the “ concert road” from Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown.

Noted as one of the “South’s Fine Hotels,” the Colony Inn had a sterling reputation for its tasty Southern cuisine. Elijah Meekins was the master chef from the Inn’s earliest days. Meals were advertised as costing 45 cents for breakfast, 75 cents for lunch, and $1,50 for dinner. The restaurant was listed in Duncan Hines’s Adventures In Good Eating and remained a popular dining and meeting place throughout its time in business. John ‘Bud’ Lankes remembered that the “dining room was a nice place to go; the food was excellent, and the Inn employed a dietician, a lady named Mildred Larkin. Local people often went there for banquets, parties, and dances.”

Dinner was a formal affair, and so gentlemen had to wear coats and tie, and ladies, dresses suitable for supper. Garland Moseley recalled going to the Inn for dinner with his parents and that he had his first taste of caviar there. The Colony Inn fit into Hilton Village perfectly with its Elizabethan appearance, inside and out, further enhancing the feeling that you were not in Warwick County but somewhere far, far away in the British Isles.

Artistic Endeavours

A Colony Inn resident often overlooked is the noted artist Thomas C. ‘Tom’ Skinner. Skinner studied at the Art Students League of New York and furthered his art studies in Spain. There he met Therese Tribolati, also an artist. The pair married in 1914 and returned to the United States. Skinner entered the field of commercial art, creating illustrations and producing commissioned murals. His maritime art expertise would result in the Skinners moving to Newport News in 1928.

Connections

Skinner’s sister, Elsie, had married Homer Lenoir Ferguson, who later became president of Newport News Shipbuilding. Accordingly, when the Colony Inn was under construction in 1928, the Skinners moved to Hilton Village. Tom Skinner painted a large mural for the Inn’s Admiral Dining Room, and Therese decorated the rooms and created original paintings for each guest room. The couple then decided to take up residence at the Colony Inn.

Official Artist

Skinner was named staff artist for the shipyard and was provided studio space there. This brought him in constant contact with the various scenes he would eventually paint, the sound of riveting hammers giving meter to his work. T.C. Skinner, as he signed his works, achieved a level of quality in maritime art seldom replicated. Homer Ferguson thought his work was “wonderful…fashioned with the eye of the draftsman.”

His official work,” according to Bill Lee of the Apprentice School, “was of the nature of portraiture; i.e. portraits of ships, and what he called ‘likeness’ was of paramount importance to him.” When Archer Milton Huntington, the shipyard owner, established The Mariners’ Museum in 1930, Tom Skinner was given the additional duty of serving as The Museum’s official artist. During his tenure there, from 1932 until he died in 1955, he produced various paintings, including a series of ten murals installed in The Museum’s Great Hall of Steam.

These paintings are bold, colorful, and almost noisy, true-to-life glimpses of the by-gone days of heavy industrial shipbuilding. His SS America painting of this fast passenger liner’s delivery in 1940 is a dramatic view of the vessel leaving the shipyard in its wake, heading seaward to its destiny. Tom and Therese were such a sophisticated and stylish couple that they gave the Colony Inn an air of the bon vivant.

The Officers’ Club

When World War II erupted, the entire Peninsula was involved in supporting the war. Major bases such as Langley Field and Fort Eustis; the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation Camp Patrick Henry; and the Newport News Shipyard made the region bustling with soldiers and war workers. The Peninsula was home to two camps for German and Italian POWs. Many of the Italians worked at Warwick County farms and as waiters at the Colony Inn.

In 1942 the Colony Inn was leased by the US Army for officers’ quarters and served as an officers’ club. First Lieutenant Charles ‘Norm’ Stevens had returned to Langley Field to train new pilots after serving as a bombardier during thirty-four missions over Germany and France. He remembered one night’s training mission, flying over Newport News teaching how to navigate with radar. Stevens wrote he “looked down on the shipyards where the welding torches below looked like blinking stars.” When off duty, he found the Colony Inn “very important to the officers stationed at Langley,” and he discovered the “solace of the Colony Inn was very meaningful to me.”

Party Time

Many nights, Langley officers would drive over to Hilton Village, which Stevens described as “a collection of steep-roofed, English style homes.” The village itself was not their destination; they were more intent on visiting the Inn’s ballroom, dining room, and bar. Young Lt. Stevens recalled approaching the Inn across a lawn under grand old shade trees. He thought it was like a “fancy officers club,” and he knew that the Colony Inn was “the only action in town” to find the fine dinner, drinks, and dancing he and his friends yearned for.

During their first visit, as they sat down to dinner, the lieutenant was “surprised that all four of their waiters are Italian prisoners of war. They speak very little English, but through sign language a few words I remember from my high school Latin class I carry on a limited conversation with some of them…I chat mainly to the man from Milan….He had been an engineer in the Italian Army and was taken prisoner at Palmero, Sicily….He tells me that Rome is the best place to go in Italy and that Naples is the worst….Naples is even worse than Newport News.” Hilton’s citizens noticed the numerous Italian soldiers working in the Inn’s kitchen, waiting tables, and maintaining the grounds. These POWs were referred to as members of the Italian Service Organization.

Dancing the Night Away

Several young ladies, like Emily Lankes Fournier, attended US-sponsored dances at the Colony Inn. Norm Stevens remembered, “I’m not a good dancer….But I summon enough courage to ask a girl to dance. We slide around the floor well enough, I carefully avoiding her toes. The band plays ‘I’ll Walk Alone,’ the music slow and sweet. The warm touch of her hand, the pressure of my arm around her waist, awake tenderness within me I had not felt for months.” Although he asked to see the young woman again, he admitted that “The chance of our getting together again is remote. And we both know it.”

Coke Highs

Lieutenant Stevens came from a teetotaling family, but it was at the Colony Inn “where I was introduced to Coke Highs — Coca Cola mixed with a shot of bourbon. The drink tastes like a refreshing Coca Cola, but the effects are startlingly different. As I sip them, I begin to feel a sense of well-being, melting away of inhibitions, a release.” Stevens had only just returned from the European combat theater a few months earlier and “had never dealt with the terror of bombing missions…All those experiences must be working on me, accumulating inside of me, like water behind a dam….Maybe that’s why a Coke High gives me such a sense of relief….Next Saturday night will again find me at the Colony Inn.”

Return to Glory

The Colony Inn continued to be a popular destination immediately after the US Army’s lease ended in December 1945. Emily Fournier recalled attending luncheons and at least one Apprentice School function there. Fournier remembered how the Inn’s entrance looked just after the war, stating that “the dining room was off to the right, once you passed through the main entrance. But if you turned left (toward Warwick Blvd.), the hotel’s registration desk was off to the right, and on the left was a big bay window with a comfortable sofa located beneath it. That area was all paneled in dark wood.”

The restaurant remained very popular. Groups like the Warwick Rotary Club moved their meetings to the Inn for a few years. Barbara Osborne Granger remembered working as a waitress in the Inn’s small breakfast room, which could only accommodate six people or so. She noted that most of her customers were shipyard executives, including former yard president Bill Blewitt. Many college students, particularly Virginia Shackelford Poindexter, remembered going to the Inn for “libations and handsome college boys.”

Unique Summer Inn Job

Charles ‘Charlie’ Tynan Jr. lived in Newport News nearly all of his life except the six years he served as a pilot in the US Air Force. Now a resident of Maryland, Tynan remembered his time working at the Colony Inn one summer during high school. He was the Inn’s handyman and groundskeeper, but some days there were other duties to perform. One morning, Charlie recalled working outside straightening up some chairs. He found some coins that had fallen out of some guest’s pockets. He told the manager about it and asked what he should do. The manager merely said, “Keep the change!”

Charlie also was called in to work as a waiter albeit dressed in his shorts and a tee-shirt. He did not mind that task as the tips were good! Sometimes he also worked as the substitute night clerk. He recalled that when the bookkeeper was on vacation for two weeks, he had to operate the “antique switchboard which required me to plug a power cord in to connect two parties. Once in a while, it would be a problem when I had more than one person on a call and would have several wires crossed at the same time. Everything went smoothly until one evening, I received a large number of calls to and from one lady. I asked the manager, who lived at the Inn, to listen in, and we decided the lady was a prostitute calling her customers. I did not get much rest, and she was not at the Inn the next day.”

Charlie Tynan thought being the substitute night clerk was the best job he had at the Colony Inn. It was easy work, and the chef would always leave him a big turkey sandwich and a Coke to help him survive the night.1

Farewell

Even though the Colony Inn was still very well maintained and beautifully kept, it was in trouble as it lacked air conditioning, elevators, and other modern appointments. The Inn faced competition from newer hotels nearby. The Inn’s owners realized the time had come to lease residential apartments and office space for doctors, dentists, and lawyers.

The south side was torn down in 1956 to make way for the Bank of Warwick. The northern section of the Inn survived four years longer, utilized as apartments until it was demolished in 1960.

The Colony Inn was a Hilton Village landmark for more than 30 years. The Inn’s ‘English style with Southern Hospitality’ added to Hilton’s look as an English country village. Sophisticated, elegant, and welcoming, the Colony Inn now remains only in the dreams of a by-gone era.

Endnote

- Charles Tynan Jr., Email message to John Quarstein, March 11, 2021.

Reference

John V. Quarstein. Hilton Village: America’s First Public Planned Community. Staunton, Virginia: American History Press, 2017.