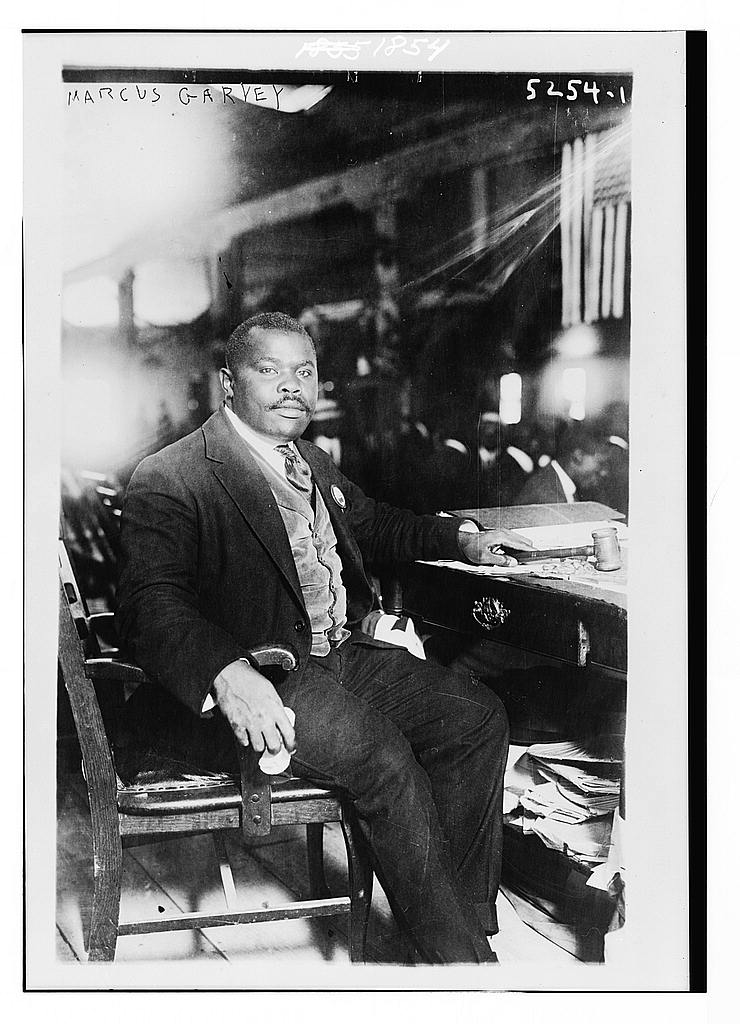

Some time ago, I wrote a post about a Black entrepreneur in the Baltimore area whose name was Capt. George Brown. As a young man he experienced the degradations of the Jim Crow system while riding the rails, vowing that one he would create a first-class transportation experience for Black people. And he did it! He also built a memorable pair of amusement parks where Black citizens of Baltimore could go and be safe and enjoy themselves. Today, I want to write about Marcus Garvey, a Black man whose dreams for ]his people were much larger, who was much more complex, and who was far more controversial than Captain Brown.

Marcus Garvey, like George Brown, believed in the power of ships and transportation to change the lives of Black people all over the world. He founded the company, the Black Star Line, as an embodiment of that dream to link the 400,000,000 people of color around the globe with the continent of Africa. But his story did not end up quite so well as George Brown’s.

Marcus Garvey and his mission

I wish I could speak authoritatively about Marcus Garvey, the man who founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA) in 1914 and the Black Star Line in 1918. I have little expertise in the area, and Garvey is such a complex figure. Add to that a shortage of archival evidence about the man, fires during the London Blitz having destroyed many of his personal papers. The FBI, who relentlessly investigated Garvey as the foremost Black “agitator” of his day, also seized and destroyed many of the papers of the UNIA.

I can, however, tell you that he was born in Jamaica in 1887, into a family of poor but well-read, property-owning people. He had ambition, and concluded very early that the problem that thwarted him was the same that faced the entire Black race. Both could be solved by a version of Pan-Africanism, that decided that there should be a strong link bringing together the peoples of the African Diaspora with the continent of Africa itself.

The seeds of a Dream

Garvey thought that he, and his UNIA, could provide such a link with a transportation company of steamships that facilitated travel back to Africa. His notion was that Black people, not colonizing Europeans, would be more successful at trading with Africans, and that there was vast untapped wealth in the continent that they, the peoples of the Diaspora, could extract at fair prices and ship to places that wanted them. With this wealth and capital, Garvey said, would come the improvement of the lot of Black people everywhere. Peoples of African descent everywhere would demonstrate their self-worth to themselves and to the world, and White peoples, seeing this, would deal with them as equals. It was, indeed, “universal negro improvement” that Garvey was seeking. The key to it all was the Black Star Line.

Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line

Before I go further into the story, I want to acknowledge two very important sources of information about the Black Star Line for me, as a non-expert. First is the really excellent blog post by Hannah Foster from 2014, found here. A second source the terrific biography by Judith Stein found in our Library called The World of Marcus Garvey: Race and Class in Modern Society (University of Louisiana Press, 1986). Where you see page numbers listed, those are from Stein’s book.

Getting it off the ground

Now all of you who know something about the transportation business will immediately grasp the problems Garvey was facing. One problem is capital, and how to get it. Captain George Brown, in Baltimore, had just enough cash to charter a steamboat from another Black entrepreneur to generate an income stream. He was an experienced mariner and also managed to keep his boats in repair at prices that did not endanger his business, which was another potential problem.

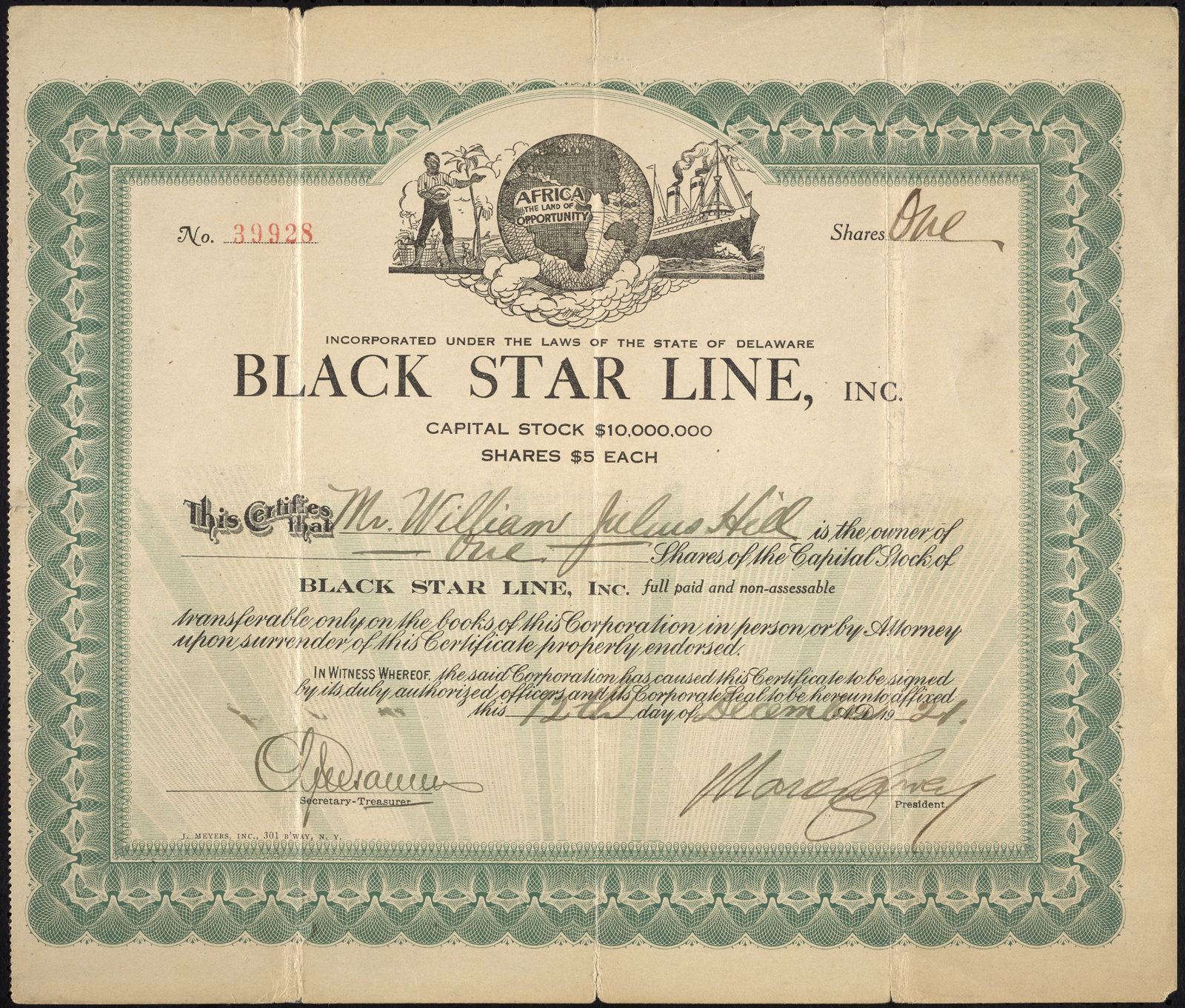

Marcus Garvey, on the other hand, hit upon another solution for capital in post-war New York: stocks. Blacks all around the country had amassed a certain amount of money from their labor during the war effort. Like everyone else, they viewed speculation as a means to get rich and were open to the idea of investing. Rather than court White institutions, Garvey’s innovation was to harness the resources of Black people, to buy one or more stocks for $5.00 apiece in the Black Star Line (p. 71). Here is an example of one sold to William J. Hill that is in the Museum’s archives.

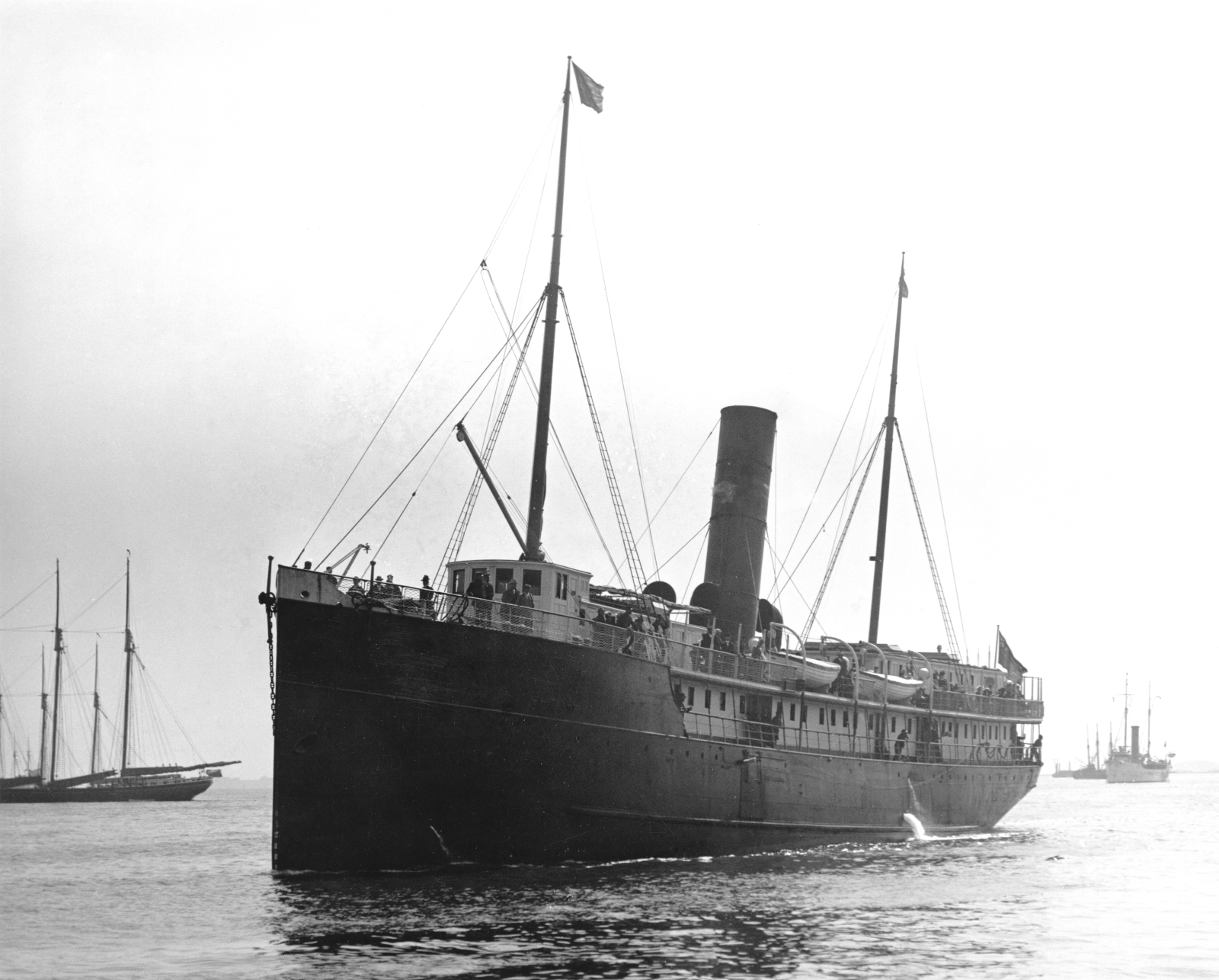

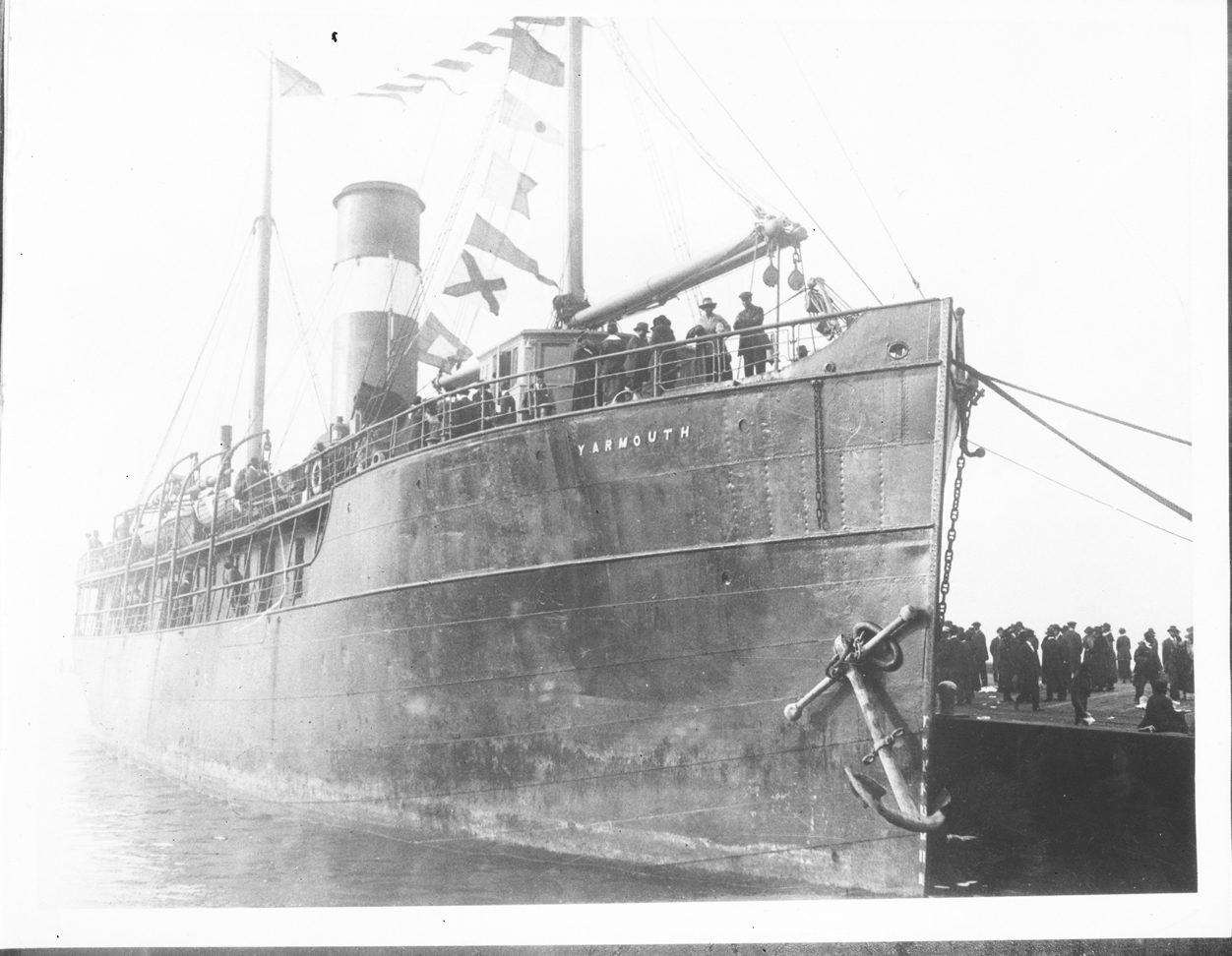

The price of even a cheap vessel for oceanic service at that time was somewhere between $150,000 and $500,000. That’s a lot of stock! But Garvey had a gift few possessed, the gift of soaring rhetoric, of a persuasive vision, and of a sense of missionary zeal. He was a magical speaker, by all accounts. He and UNIA chapter members managed to buy eventually 3 ships: Yarmouth (1887), Shady Side (1873), and Kanawha (1899). Yarmouth, the first, was to be renamed Frederick Douglass.

Dealing with the practicalities of owning ships

SS Yarmouth

So Garvey and UNIA were making a go of getting the capital together! But then the second problem arose. Unlike George Brown, none of them knew anything about the business. They made, honestly, terrible business decisions. The vessels they bought were old and worn out. Yarmouth sprang a leak on its first outing and needed repair on its return. Garvey felt pressure to get the ship back out with a cargo of distilled liquor that he negotiated a price by the ton for. The experienced master of Yarmouth blew up at him, told him that the yard had not fitted her out for transporting liquor, and that his price per ton was ridiculously low for such a cargo. Garvey also had decided to allow an engineering firm to repair Yarmouth that essentially fleeced him. It was emblematic of the business problems the UNIA and Garvey faced.

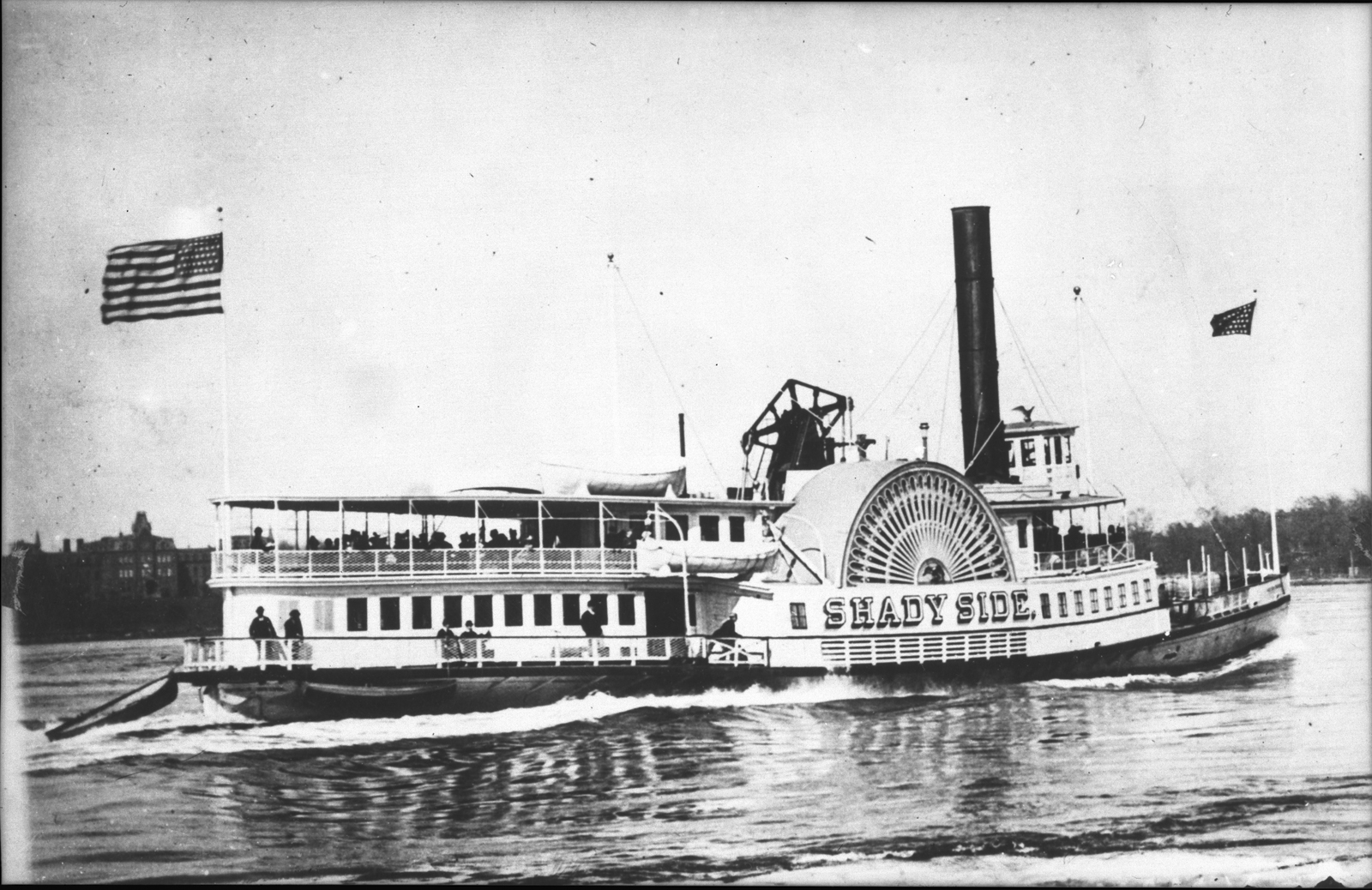

The side wheel steamer Shady Side

So UNIA decided to sell even more stock to buy more ships, to try to dig themselves out of the hole they were in. The owner of Shady Side, a Hudson River ferry, persuaded Garvey that she would be an excellent summer excursion boat from which he could make a huge profit (p. 94). So Garvey bought it, and operated it in the summer of 1920. Over the winter, however, whether from rot, from ice or from storm, she sank and her owners declared her a total loss. Black Star Line had to take the insurers to court for the $5,000 claim that they refused to pay.

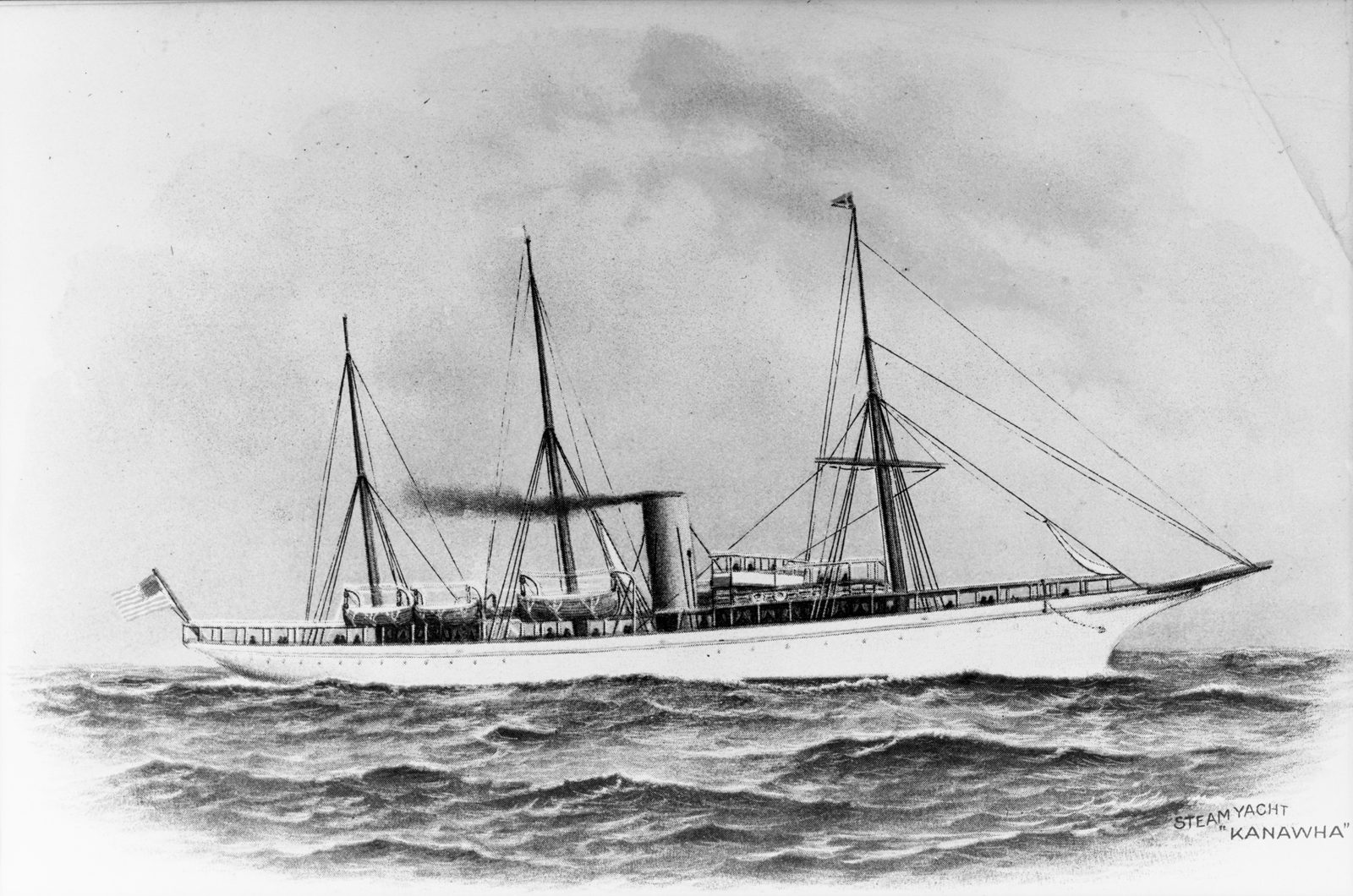

Steam yacht Kanawha

UNIA also bought the Kanawha, a small yacht that Garvey said would be useful for the inter-Colonial trade in the Indies. However, the price he paid for the 375-ton vessel, about $60,000, was exorbitant. A merchant mariner friend warned Garvey that the boat’s operating expenses would exceed its purchase price. He also pointed to defective boilers and auxiliaries, but Garvey went ahead anyway (p. 96). A boiler explosion on her first trip as the Antonio Maceo killed a crewman. The Coast Guard towed her back to New York, never to sail again.

Garvey’s Dream of the Black Star Line Destroyed

To top it all off, UNIA had to siphon off the proceeds from the sale of stocks to fund the budget deficit caused by a failed restaurant venture (p. 89). The Black Star Line was, by 1922, practically bankrupt.

The court case: Garvey Vs. U.S.A.

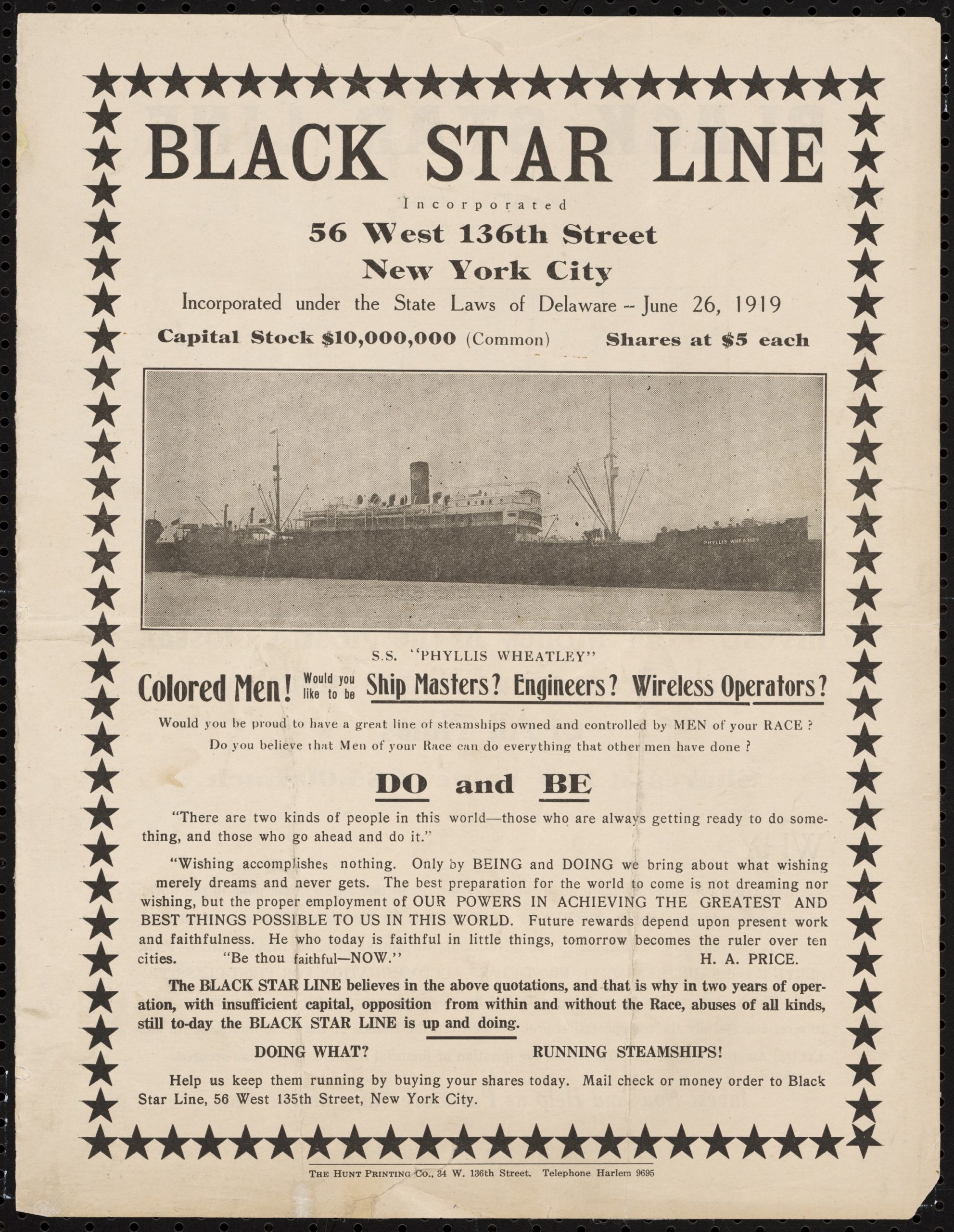

All of these business problems and improprieties came out in a federal court case, Garvey v. U.S.A. Federal authorities arrested Garvey on Jan. 12, 1922, and a grand jury indicted him for mail fraud on Feb. 16 (p. 192). The indictment claimed that the UNIA’s mailer soliciting funds for a ship named Phyllis Wheatley was fraudulent, because they implied that Black Star Line already owned her. They did not own her, in fact. They were looking for a ship to buy they would name Phyllis Wheatley.

By this time, Garvey’s many enemies, both within the Black community and without, gave evidence against him. The FBI, who under J. Edgar Hoover wanted to frame Garvey’s political activism as a communist threat, had been looking for a deportable charge against him for years. They found this one. A jury found Marcus Garvey guilty in March of 1923. The judge in the case, whose fairness at the trial drew praise from black journalists, ended up imposing the maximum sentence after Garvey damned his entire ethnic group (the judge was Jewish) in public. Despite appeals, and with an official pardon from President Calvin Coolidge, Immigration authorities deported Marcus Garvey on Dec. 2, 1927 (p. 207).

A Mariners’ Museum connection

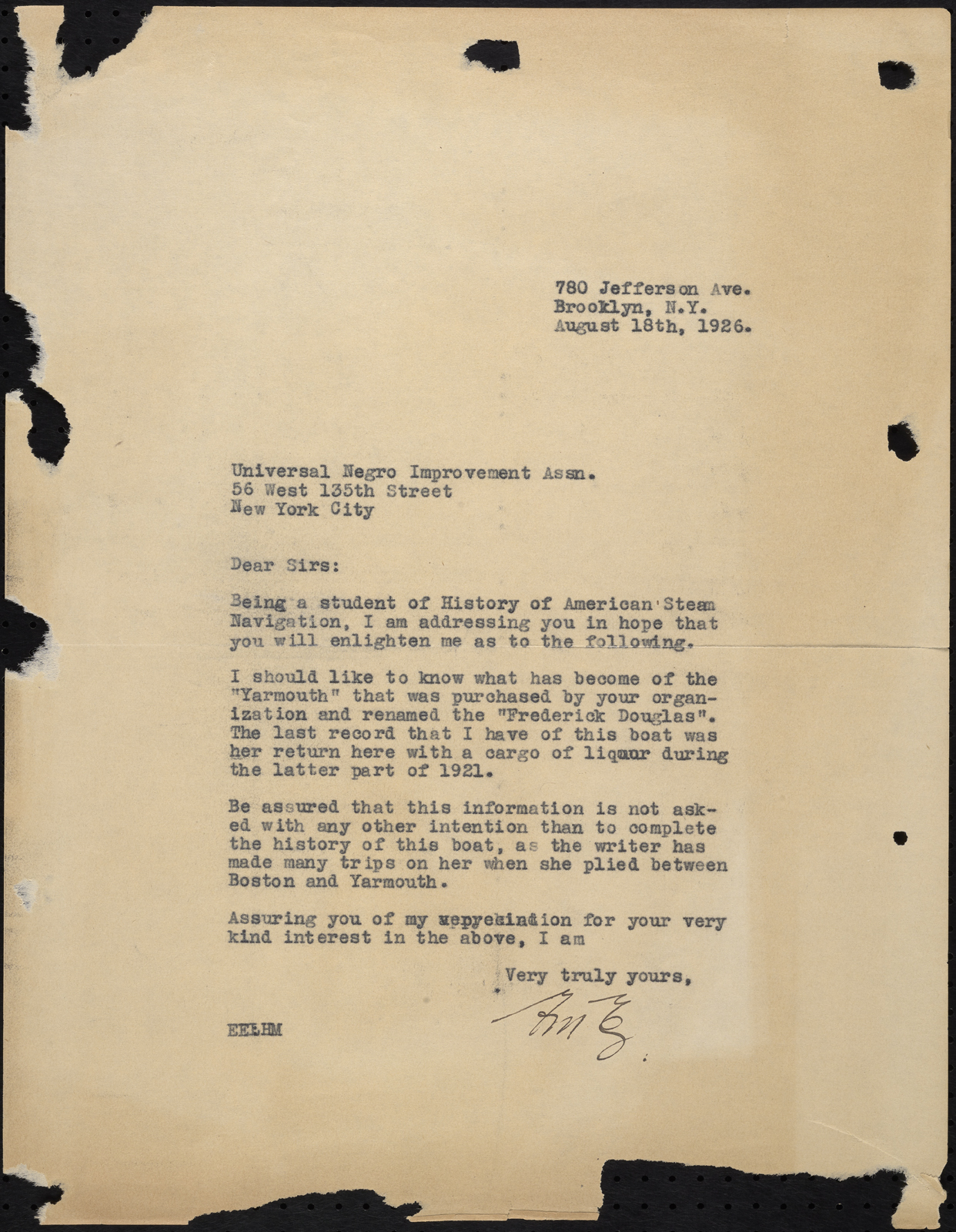

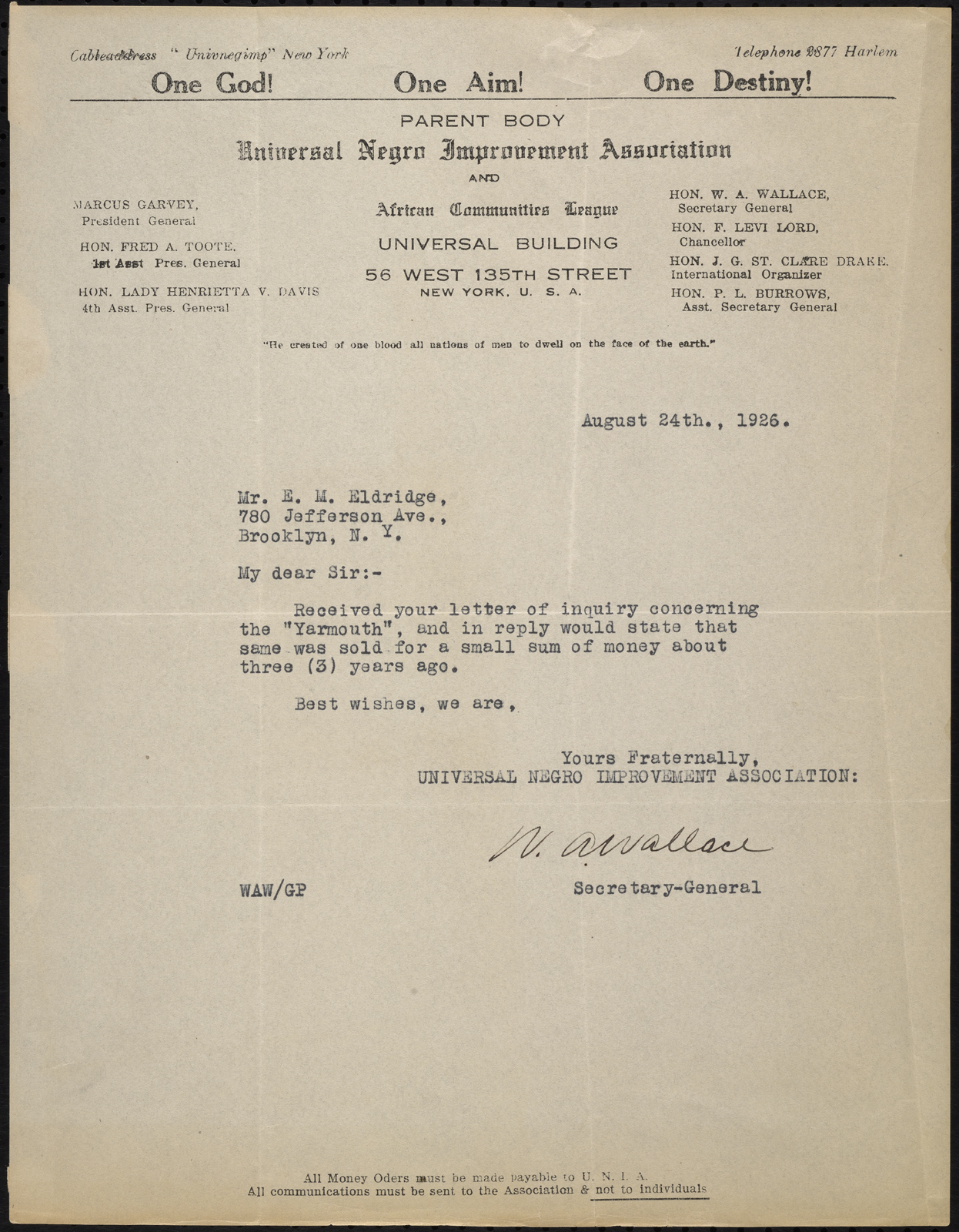

An interesting coda to this saga is that in our collections is a folder of Black Star Line materials in the Elwin Eldredge Collection. Eldredge, who refers to himself as a “student of History of American Steam Navigation”, wrote a letter to the UNIA merely trying to find out what happened in all this to the Yarmouth. It was a ship he had sailed in many times, he writes. A letter came back on UNIA letterhead. You can read the contents of both these letters below.

My takeaway

Marcus Garvey lived in a different world from the one we find ourselves in today. He was, and remains, a lively and controversial figure. But for me, and for The Mariners’ Museum and Park, he is something of a forerunner. He believed in the power of ships to bring people together, people who are naturally connected to each other despite the miles and the oceans that keep them apart. And he created an institution, the UNIA, that he believed would ultimately “promote the public welfare,” just as Archer Huntington did when he created this Museum. He wanted Black people to believe in themselves and elevate themselves. I think he’d agree with my favorite drag superstar, RuPaul, when he says, “If you can’t love yourself, how the hell you gonna’ love somebody else? Can I get an Amen! up in here?” I think we could all use a dose of that.