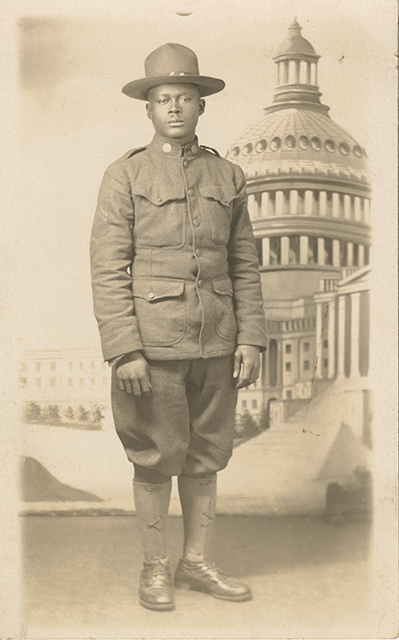

He stands there, tall and proud, gazing into the camera, a backdrop of the United States Capitol behind him. Dressed in a high-collared wool uniform with a corporal’s rank insignia sewn on his right sleeve, Benjamin Harrison Splowne had reason to beam. Drafted in June 1917 into the National Army, he was promoted to the rank of corporal within a few months of his induction.

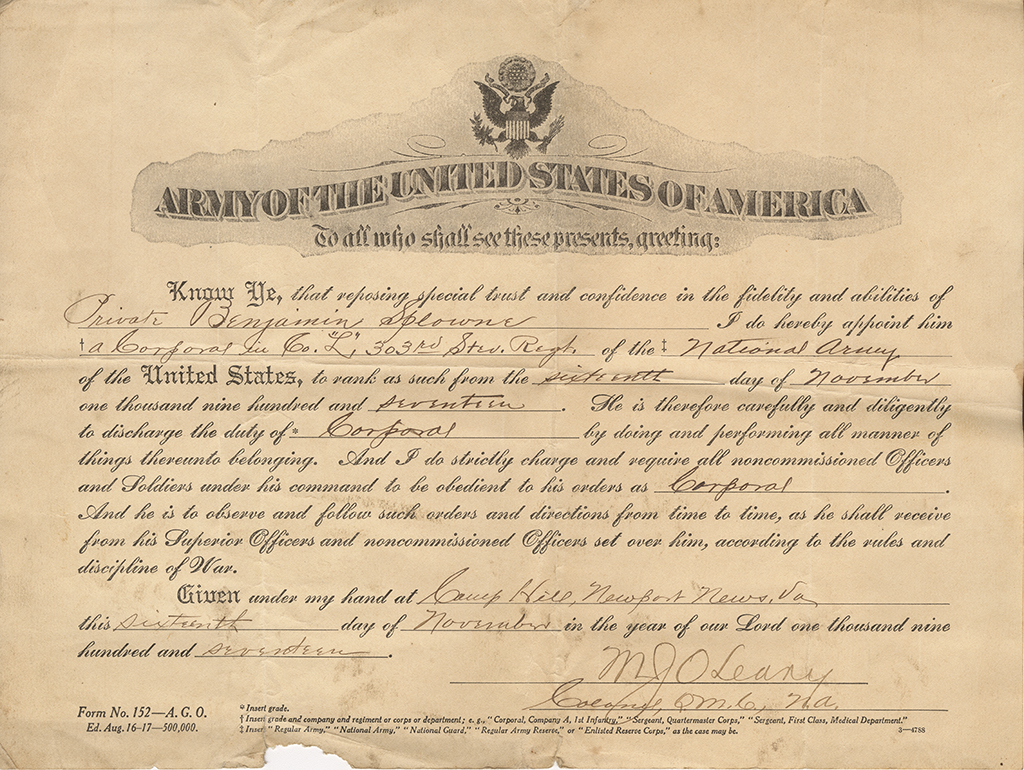

Exactly where and when this photograph was taken is subject to speculation. It is conceivable that it was taken in Newport News, as Benjamin Harrison Splowne was stationed at Camp Hill, Virginia for a brief while in 1917. In fact, he was promoted to corporal on November 16, 1917 at Camp Hill, shortly before shipping overseas. The Museum is fortunate to have his promotion certificate, along with his studio portrait, for they help document the often-overlooked role of African American soldiers during World War I, both in Newport News as well as abroad.

As Adriane Lentz-Smith relates in her work on African American and World War I, nearly 400,000 African Americans served in the armed forces during the war, with over 200,000 of them serving overseas. Serving in a segregated Army, Blacks were keenly aware of the opportunities and challenges that service provided. In Lentz-Smith’s words, “serving America meant establishing their central place in the national community and reaffirming their foundational place in the state. For African American soldiers, serving America also meant proving their manhood – asserting themselves as courageous and capable, independent and deserving of honor.”[1] Many wanted to prove that “Colored Man is No Slacker,” as the poster from 1918 illustrated below states, albeit using language that we would not use today.

Newport News in the Great War

The Port of Embarkation was established in Newport News in early 1917. In the months that followed there was frenzied construction of the camps and infrastructure that would allow the United States to ship more than 288,000 American troops and 58,000 horses and mules, along with millions of tons of equipment, supplies, and ammunition through the Port of Embarkation to the fighting fronts in Europe. Newport News would become the second largest port of embarkation in the United States.

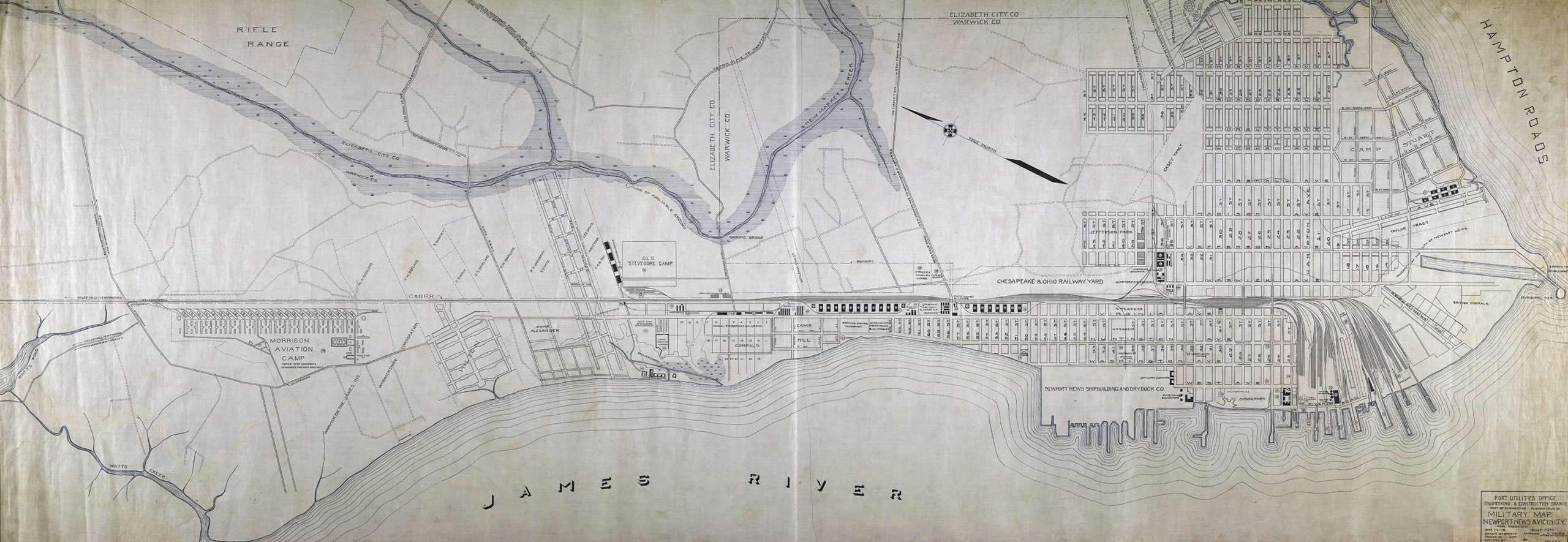

In order to accommodate the troops and material moving through the port, the Army built four military camps, each serving a specific function. The camps can be seen in the map below.

Camp Stuart, the largest camp, was built to house entire units of soldiers awaiting transport overseas. It is in the upper right corner of the map.

Camp Hill, located just north of the Newport News city line, handled motor vehicles and the Animal Embarkation Depot.

Camp Morrison consisted of supply warehouses and staging areas for Army Air Service personnel. It is in Warwick County, just beyond Hilton Village.

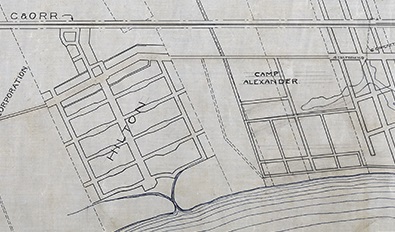

Located between Hilton Village and Camp Hill, Camp Alexander housed African American soldiers, in line with the segregationist policies of the United States Army of that era.

Camp Alexander

Camp Alexander was established in August 1917 as part of the Port of Embarkation. Named for Lt. John H. Alexander, the first African American graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, it was used as a “temporary quartermaster camp, consisting of a stevedore cantonment and labor battalion encampments, located on east bank of James River, Warwick County, immediately north of Camp Hill, and about 3 miles from Newport News.”[2] A detail from the above map shows Camp Alexander adjacent to Hilton Village. Administratively, Camp Alexander fell under the jurisdiction of Camp Hill.

Camp Alexander had the capacity to house nearly 10,000 troops. This included stevedore and labor battalions slated to ship overseas, in addition to port support personnel. Unfortunately, very few images of Camp Alexander and the men who passed through there are known to exist. Corporal Splowne will have to stand in for his many compatriots.

Corporal Benjamin Harrison Splowne

Benjamin Harrison Splowne was born in Stephens City, VA on February 1, 1890. According to his draft card, dated June 5, 1917, he resided in Montclair, New Jersey but worked in a blast ice lab for A.M. Manufacturing Company in Dunbar, Pennsylvania at the time of his induction. Assigned to the 303rd Stevedore Regiment, Quartermaster Corps, National Army, he arrived in Newport News and trained while waiting to be shipped overseas.

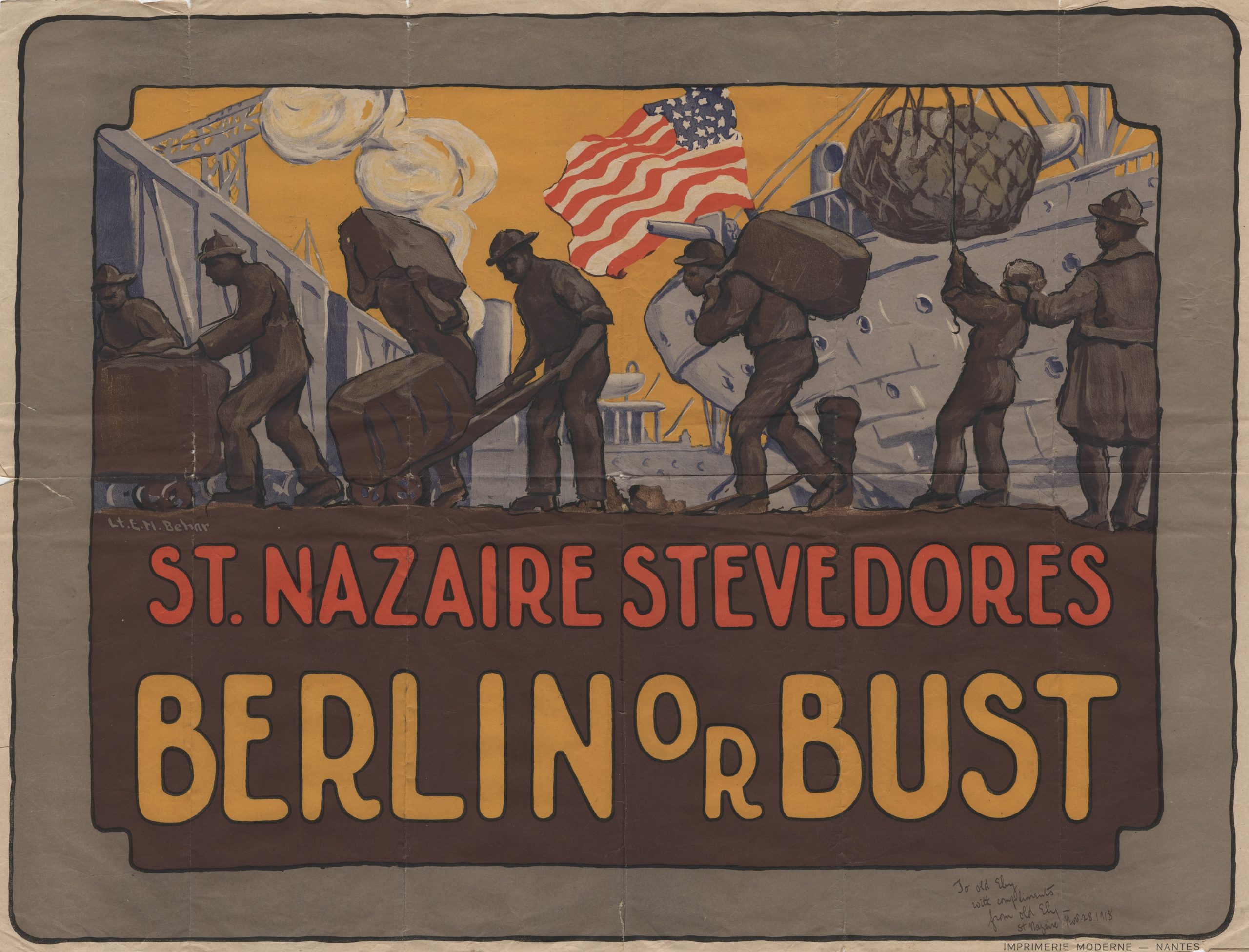

Like so many of the Stevedore Regiments, the 303rd was destined to serve overseas. Little did Splowne and the members of his regiment know that instead of shipping out of the nearby port of embarkation, the regiment would sail out of Hoboken, New Jersey on December 4, 1917, on board George Washington. Shortly after its arrival in France, the 303rd Stevedore Regiment was transferred from the Quartermaster Corps to the Transportation Corps, and broken up into the 813th, 814th, and 815th Stevedore Battalions. Unfortunately, I have not yet been able to learn with certainty which battalion Splowne was assigned to. I can state with certainty that Splowne returned to the United States in July 1919, sailing from St. Nazaire on board USS Eten.

Stevedores Overseas

More than 200,000 African American soldiers served in France. The vast majority worked in service units organized under the Service of Supply, unloading provisions and equipment destined for the front lines. Emmett Jay Scott, a prominent author, journalist, and confidant of Booker T. Washington, served as Special Assistant for Negro Affairs to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker during the war. He noted that the work of the “Negro Stevedore Regiments and Labor Battalions, and their unremitting toil at the French ports – Brest, St. Nazaire, Bordeaux, Havre, Marseilles—won the highest praise from all who have had an opportunity to judge of the efficiency of their work. Every man who served his country in one of these organizations was as truly fighting to save his country as though he had carried a rifle and killed Germans.”[3]

The poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox, perhaps best known for her poem, Solitude, visited France in 1918. According to Scott, she read her poem, The Stevedores, in front of a large crowd of African American servicemen.[4]

The Stevedores

We are the Army Stevedores, lusty and virile and strong;

We are given the hardest work of the war, and the hours are long.

We handle the heavy boxes and shovel the dirty coal;

While soldiers and sailors work in the light, we burrow below like a mole.

But somebody has to do this work, or the soldiers could not fight!

And whatever work is given a man, is good if he does it right.

We are the Army Stevedores and we are volunteers;

We did not wait for the draft to come, to put aside our fears.

We flung them away to the winds of fate, at the very first call of our land,

And each of us offered a willing heart, and the strength of a brawny hand.

We are the army stevedores, and work as we must and may,

The cross of honor will never be ours to proudly wear away.

But the men at the front could never be there,

And the battles could not be won,

If the stevedores stopped in their dull routine

And left their work undone.

Somebody has to do this work, be glad that it isn’t you!

We are the Army Stevedores – give us our due![5]

Giving Stevedores their Due:

The patriotic service of African American stevedores like Benjamin Harrison Splowne at home and abroad during World War I was critical for the successful outcome of the war. We should strive to remember the service of individuals whose identities are known to us, along with those whose names have faded from our collective memory. More importantly, we must continue to commemorate the service of every American who served in the Great War. It took all Americans to make the world “Safe for Democracy.”

Suggestions for further reading:

Lentz-Smith, Adriane. Freedom Struggles. African Americans and World War I. Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Rainville, Lynn. Virginia and the Great War. Mobilization, Supply and Combat, 1914-1919: Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarland and Company, 2018.

Scott, Emmett Jay. Scott’s Official History of the American Negro in the World War. Homewood Press, 1919. In particular, see Chapter XXII, The Negro in the Service of Supply.

Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War. Zone of the Interior: Territorial Departments, Tactical Divisions Organized in 1918, Posts, Camps, and Stations, Volume 3, Part 2. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1988.

Wilcox, Ella Wheeler. Hello, Boys! London: Gay and Hancock, Ltd. 1919. Project Gutenberg eBook: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6666/6666-h/6666-h.htm, accessed Feb. 19. 2021.

Endnotes

[1] Lentz-Smith, p. 5.

[2] Order of Battle, Vol. 3, part 2, p. 711f.

[3] Scott, p. 316.

[4] Scott, p. 326.

[5] Wilcox, p. 59.