Ever since man first set foot in a boat and headed out to sea there has been a need for pilots. Sailing in deep water is easy (as long as a storm doesn’t catch you!); navigating the shallower waters along coastlines and entering ports and rivers you aren’t familiar with is a lot more dangerous.

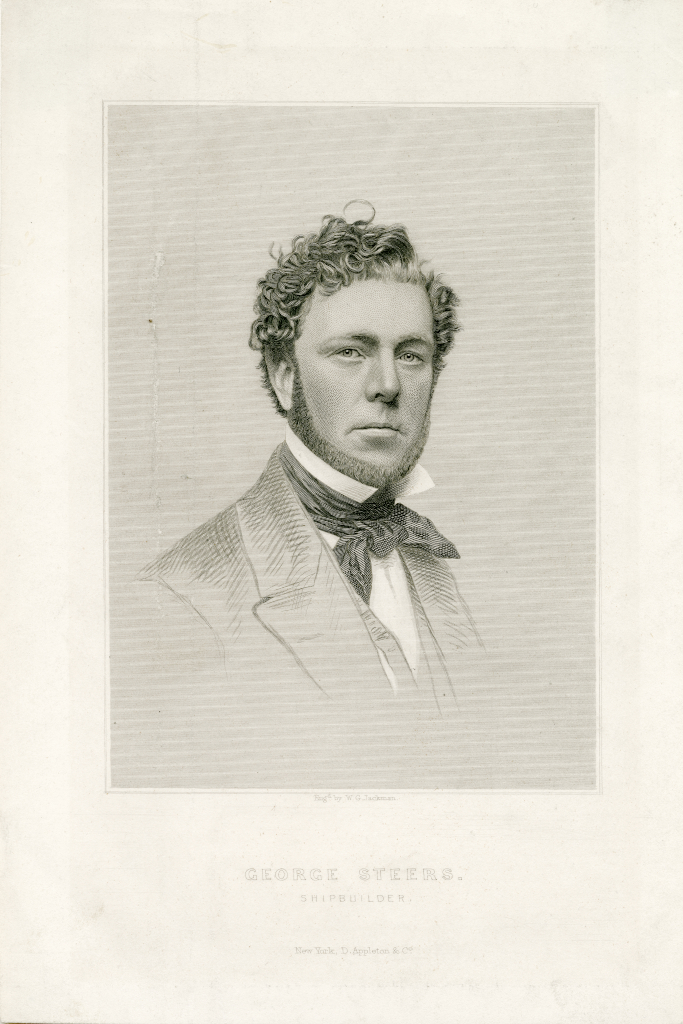

In mid-19th century New York the competition to provide pilotage services to an ever increasing volume of commercial traffic was fierce. Since the first pilot boat to reach an inbound vessel typically got the job the pilot’s need for a fast sailing boat was paramount. As this need increased some of the world’s most talented yacht designers and naval architects jumped into the fray and began designing some of the fastest schooners the world had ever seen. One of these men, New York’s George Steers, ended up designing boats that changed the face of naval architecture forever.

George Steers designed his first pilot boat, the William G. Hagstaff, in 1841 when he was just 21 years old. Built for the New Jersey pilots, Hagstaff was reputedly very fast and easily passed the boats used by competing New York pilots. Unfortunately we don’t know anything about Hagstaff’s construction and her life as a pilot boat was short lived. In 1849 Hagstaff’s owner sailed her to the West Coast with the intention of establishing a pilotage business at the mouth of the Columbia river. Unfamiliar with the hazards of the local waterways Hagstaff grounded on a bar in the Rogue River (sometimes even pilots need pilots!). A short time later the stranded vessel was attacked, robbed and burned by the local Tututni Indians.

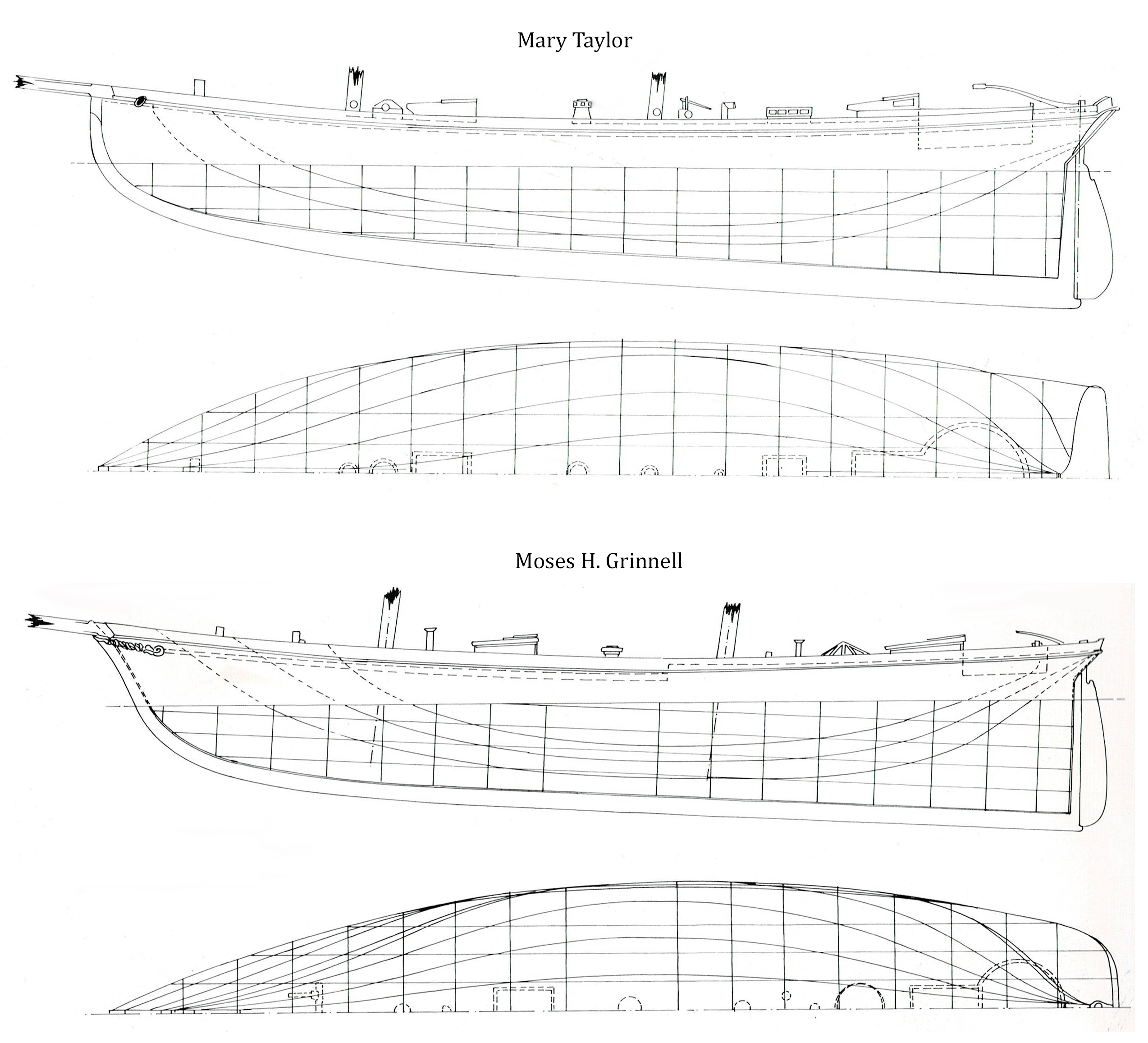

Captain Richard Brown had served aboard the William G. Hagstaff and when he and a partner decided to build a new, faster pilot schooner they immediately turned to George Steers. When Steers presented Brown with his designs for Mary Taylor Brown’s first reaction seems to have been “are you sure?”. His anxiety was justified as Steers’ design of Mary Taylor’s hull was completely different from nearly every other craft sailing of the time and a radical departure from the standard practices of the day.

When Mary Taylor was designed (1848) most sailing craft were built with wide bows (considered necessary to prevent the vessel from diving under the waves) and narrow sterns. Wide bows force a boat to push the water aside as it moves forward which creates considerable drag and slows the boat down. For Mary Taylor Steers flipped traditional design on its head and created a boat with a narrow bow and stern and its greatest width near the middle of the boat. Her shallowest draft was all the way forward and it gradually increased to her deepest draft at the stern. The result was a supremely stable schooner that handled rough seas well and sailed faster than every other boat of her size.

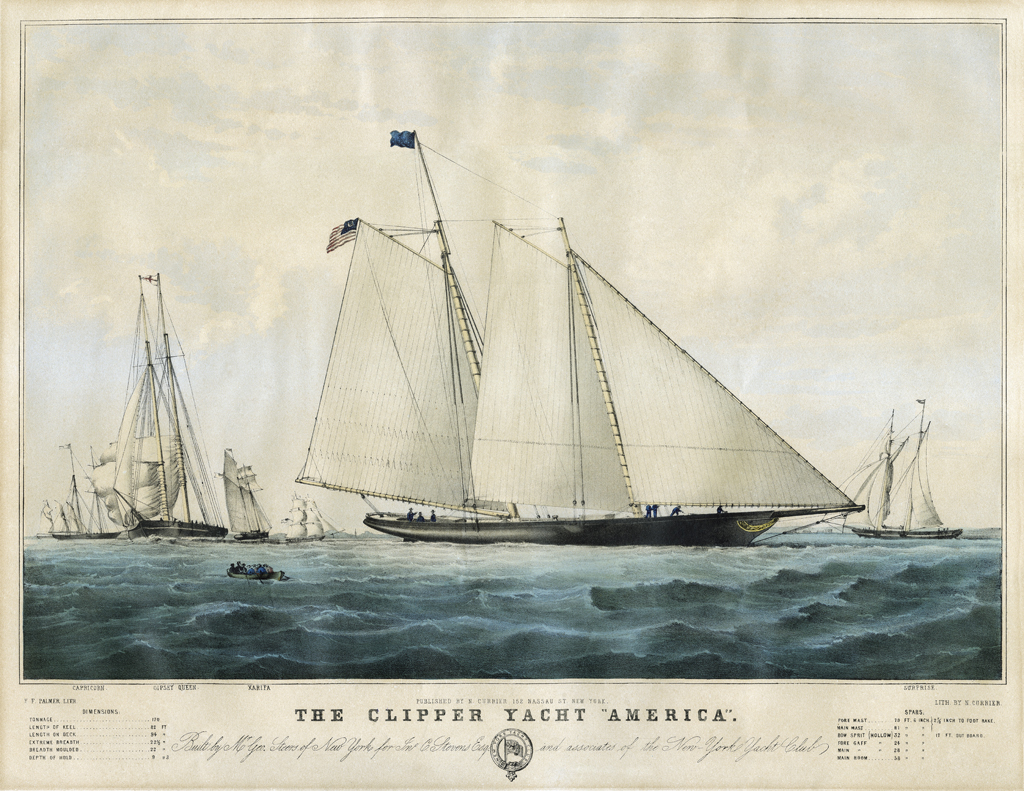

Mary Taylor’s design was so good it served as the basis for Steers’ design of the yacht America. As most of you probably know, in 1851 America beat fifteen vessels of the Royal Yacht Squadron in a race around the Isle of Wight and started the world’s oldest sailing competition—the America’s Cup. Unfortunately Mary Taylor’s great speed and maneuverability didn’t prevent her from being run down by the US transport Fairhaven off Barnegat Bay in November of 1863. Everyone on board was saved, but the accident sent a historically important vessel to the floor of the Atlantic.

Following the success of Mary Taylor the design of Steers’ next pilot boat, Moses H. Grinnell, was even more radical. Steers gave Grinnell a long, sharp entry and a fully concave clipper bow—one of the most extreme entries seen on any sailing vessel to that point. Steers himself described the shape as “the well-formed leg of a woman” (I’m not sure whose leg he was looking at–I don’t see it!). Moses H. Grinnell was reputedly very fast. In May of 1851 Grinnell won a race around the Sandy Hook lightship and back against the new schooner yacht Cornelia (also designed by George Steers).

Moses H. Grinnell had a long career. She served the New Jersey pilots from 1850 until sometime around 1880 when she was sold to the Boston pilots. Just a couple of years later she was sold to the Pensacola pilots. In 1909 she was sold to the Mobile pilots where she worked until 1914 when she became a merchant vessel in Jamaica. She finally disappears from the register in 1924.

Grinnell’s long life is remarkable considering she suffered several terrible accidents. In October of 1863 she was very nearly run down by the 1,114-ton US Supply steamer Union but her crew managed to keep her afloat until they made it back to port for repairs (obviously the crew of Union weren’t paying much attention because the same night they ran over and sank the brand new pilot boat James Funck). A few years later in October of 1871 Grinnell collided with two foreign barques and had to be run ashore to prevent her from sinking.

Building upon the designs of Mary Taylor and Moses H. Grinnell Steers’ next pilot boat, named after himself, was considered by Howard Chapelle to be the finest pilot schooner ever built. Chapelle described George Steers as “stunning” and an example of Steers’ “mature practice.” He thought her design was an improvement over the yacht America and felt “the balance of her ends” was “quite remarkable.” Although George Steers was built for speed her depth insured she remained seaworthy and stable in rough weather—important factors that would help her survive the terrible weather she would encounter during her working life. Unfortunately even the best designed vessel can’t always withstand Mother Nature’s wrath. On February 12th, 1865 George Steers was driven ashore near Barnegat during a terrible winter gale. There were no survivors.

The perfection of pilot boat design was reached with the George Steers and most pilot boats built thereafter were similar in design. The last pilot boat designed by George Steers was the Anthony G. Neilson. Built for a group of Sandy Hook pilots and launched in 1854 she was reputedly one of the fastest pilot schooners in New York (her only competition being her sister George Steers.) She was sold to a group of New Orleans pilots in 1859 and used until sometime around 1872 when she was sold for use as a cargo vessel.

Sadly, just two years after designing Neilson George Steers died after being thrown from a wagon. He was just 37 years old. Although we’ll never know if he was considering further refinements to his pilot boat designs his efforts up to that point had a huge impact on yacht design and naval architecture in general.