Jason Copes/The Mariners’ Museum and Park

The Mariners’ Museum 1969.0001.000001A_01a

Early European explorers and settlers to Virginia found that the Indigenous population had a successful watercraft of their own: the dugout canoe. Canoes were laboriously crafted from a single log. A fire was allowed to slowly burn into the wood and the accrued char was scraped away using a stone or oyster shell. The resulting vessel was durable, stable, and capable of carrying between 10 and 20 people.

The Mariners’ Museum E141 .B91 Rare O_1590

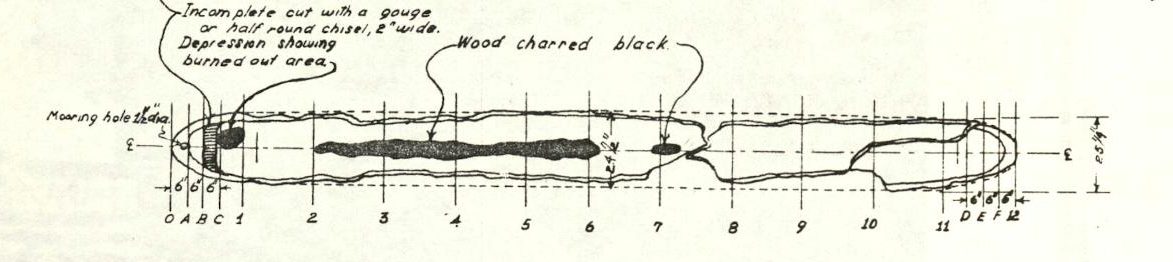

The Mariners’ Museum and Park holds a single colonial-era canoe. And it’s pretty interesting. The artifact was discovered by fishermen in Powhatan Creek (James City County) in 1963 and housed at Jamestown Festival Park until it was gifted to the Museum in 1969. Composed of three major fragments, the canoe would have originally been over 26 feet in length with a width of around 25 inches. The wood is pine and an approximate count of the annual growth rings would have put the source tree at more than 200 years old.

The Mariners’ Museum in 1969 1969.0001.000001A_bu51

What makes this particular artifact unique is that it shows signs of two differing boatbuilding traditions! Classic native burning and scraping techniques are particularly evident from a deeply burnt scar inside the bow and another long scar along the bottom interior.

The Mariners’ Museum 1969.0001.000001A_bu51b

However, the canoe was further shaped using metal tools (an adz or gouge), creating sharper angles to the bow and stern, flattening the bottom, and removing wood from the interior, likely to reduce weight.

Brock Switzer/The Mariners’ Museum and Park

The Mariners’ Museum 1935.0551.000001

The combination of native and European techniques strongly suggests that the canoe was originally indigenously built and later acquired (and modified) by early settlers. Dr. Ben C. McCary (1901-1995), an archaeologist at the College of William and Mary, posited that the canoe dates to circa 1630, a time when Native Americans and English settlers coexisted on the Peninsula.

The Mariners’ Museum 1969.0001.000001A_inCBG

The canoe was last on display in the Chesapeake Bay Gallery from 1989 until 2013, when that exhibit was retired. The artifact currently resides in storage. Given the fragility of the canoe, future exhibition is unlikely without a major conservation effort.

Jason Copes/The Mariners’ Museum and Park

The Mariners’ Museum 1969.0001.000001A_detail