During the colonial era European conflicts often spilled over into colonies along the Atlantic seaboard. Caribbean islands produced sugar; Southern Atlantic colonies produced cotton, tobacco, and ship stores; and the Northern Atlantic colonies were famous for furs and lumber. As the Europeans fought, they likewise sought to control all of their enemies’ commerce and resources.

The Anglo-Dutch Wars were a series of three 17th-century conflicts fought for control of worldwide trade; and were mostly conducted by naval warfare. Both the Netherlands and England were rapidly expanding commercial nations, and each wished to control these vast profits. To do so meant that either England or the Netherlands had to destroy their enemies’ fleet, conquer or raid their colonies, and capture or disrupt their merchant marine. The Second and Third Anglo-Dutch naval wars involved both the Dutch and English and this fierce economic rivalry brought these wars to the shores of Hampton Roads.

The Navigation Acts

The “Acts of Trade and Navigation” were a series of English laws designed to control English shipping, trade between other countries, and its own colonies. These laws were based on mercantilist theories that England was to profit and control the majority of worldwide trade. The acts detailed that only English ships would be allowed to bring goods into England and that North America and all other English colonies and trading posts in places like West Africa, the Caribbean, and Bombay could only sell their commodities to England. The Navigation Acts, beginning in 1651, were protectionist laws especially designed to destroy Dutch commerce through the control of maritime trade routes and overseas resources. These acts resulted in three naval wars between the two maritime powers, the first being fought between 1652 and 1654.

Second Anglo-Dutch Naval War

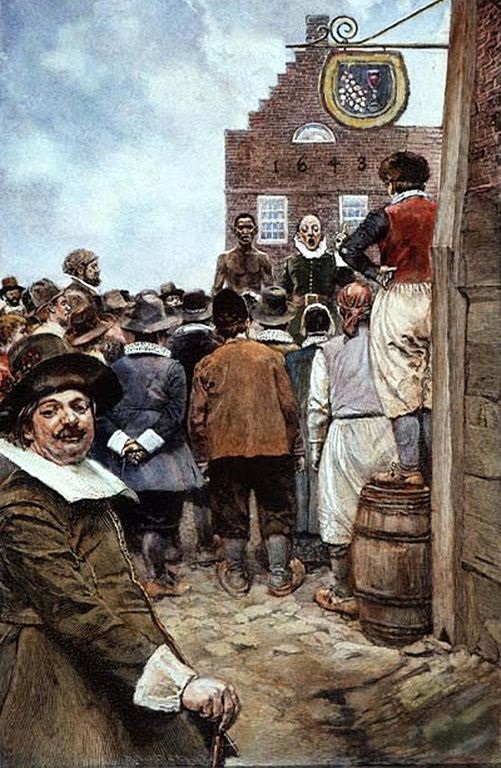

The first naval conflict did not resolve the trade competition between England and Holland. “What matters is not this or that reason,” noted George Monck, the Duke of Albemarle. “What we want is more of the Dutch trade.”{1} The English wished to overtake or end the Dutch leading position in world trade. The English began to bully their way into taking over the Dutch slave trade by capturing the Dutch East Indies Co.’s Cabo Verde slave trading post in West Africa. Then they conquered the Dutch North American colony known as New Amsterdam beginning in June 1664. After the English captured two Dutch convoys in early 1665, the Netherlands declared war on England on March 4, 1665. While the war initially went well for the English, the Royal Navy was overtaxed to defend the approaches to England itself as well as its overseas empire.

Following the First Anglo-Dutch Naval War, the Dutch improved their fleet while England lacked the finances to expand the Royal Navy at the same rate. After the English victory during the July 25, 1666, St. James’s Day Battle, King Charles II thought that the Dutch fleet was so severely beaten that he laid up most of his heavy ships at Chatham on the River Medway. He just could not pay his crews. Between June 19 and 24, 1667, the Dutch sent a fleet into the Thames and Medway to destroy and capture numerous major English ships.

Consequently, English morale was at a low point. The Black Death had visited the nation in 1665 to 1666, resulting in more than 100,000 deaths; and the Great Fire of London in September 1666 had destroyed much of the city. The Dutch, because of their great victory in the Medway in 1667, now appeared to be in control of the seas and turned their attention to the British overseas empire.

Defending the Chesapeake

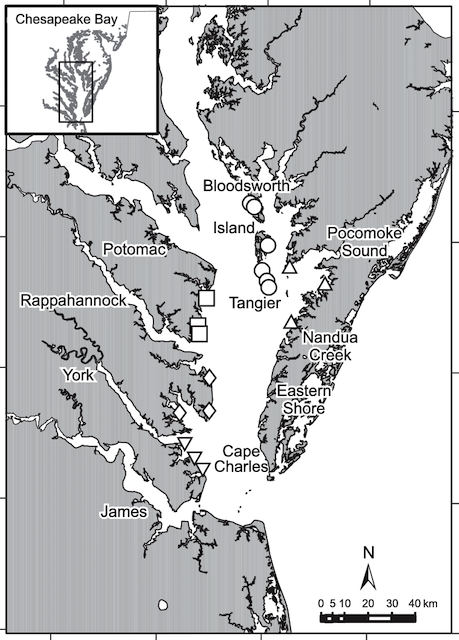

When the war between England and the Netherlands erupted in 1665, Virginia was virtually defenseless. Governor Sir William Berkeley received instructions on June 3, 1665, from King Charles II to ready Virginia to repel any Dutch invasion or raid. Hampton Roads, Virginia, was the roadstead for the annual tobacco fleet convoy which took valuable Virginia and Maryland product to England each year. As Berkeley endeavored to organize the militia, he knew that the greatest danger was to the tobacco fleet. He lobbied London for cannons and powder. Berkeley decided to identify four defensive anchorages including: Jamestown, Tyndall’s (Gloucester) Point on the York River, an unnamed site in the Rappahannock River, and Pungoteague on the Eastern Shore.

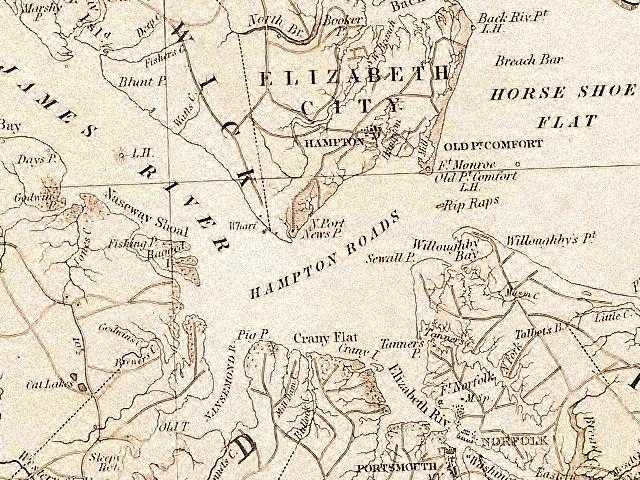

Berkeley planned to abandon the fort on Old Point Comfort and remove its cannons to Jamestown. The fort at the entrance to Hampton Roads had been rebuilt in 1632 and had fallen into disrepair. The governor did not believe that any defenses on Old Point Comfort could effectively defend Hampton Roads. Nevertheless, the King and his Council thought otherwise and ordered that the derelict fort be rebuilt.

Berkeley believed that the colony’s militia, commanded by leading citizens like Colonel Leonard Yeo of Elizabeth City County and Colonel Miles Cary of Warwick County, would be capable of repelling any land invasion of Virginia. Yet, he feared that the riverine fortifications were incapable of guarding the colony or the tobacco fleet, and he requested that a frigate be sent to Virginia to act as a guard ship. The Admiralty complied; however, the vessel sent was indeed a relic. The HMS Elizabeth was built in 1647 as a 32-gun frigate. The ship was worn out and it appeared to the Lord High Admiral that the Chesapeake was where it could do the best service.

When Elizabeth arrived in the James River, it delivered 10 cannons to Jamestown. The frigate’s commander, Captain Lightfoot, discovered that the forts planned for the York River, the Rappahannock River, and the Eastern Shore were useless. Furthermore, his own ship was in such bad condition that it required extensive repairs. Virginia remained unprepared to protect the tobacco ships that were assembling in late April in Hampton Roads and the James River.

The Dutch Strike Like a Crimson Tide

Admiral Abraham Crijnssen, a hero of the Four Days’ Battle, was dispatched to the Caribbean on December 30, 1666, to coordinate with the Dutch’s newest ally, France, to capture or re-capture various English possessions. Crijnssen (called “Crimson” by the English) successfully re-captured Suriname, Tobago, and St. Eustatius. Yet, he found it exceedingly difficult to work with the French navy and decided to sail to the Chesapeake Bay.

Crimson had several warships under his command including: the frigates Zeelandia (34-guns), West-Cappel (28-guns), and Zerider (34-guns). As the Dutch fleet neared the Virginia Capes, the Dutch captured a small shallop. The crew members told Crimson that almost 20 tobacco ships were at the mouth of the James River. Then, the Dutch encountered a 20-gun merchantman commanded by Captain Robert Conway of London. Its destination? Tangier Island. Conway valiantly resisted the Dutch; however, he was forced to surrender. Conway was given the captured the shallop Pauls Grave in return for guiding Crimson’s fleet into the James River.

On June 5, 1667, the Dutch ships, flying English colors, sailed right into the tobacco fleet and steered toward the frigate Elizabeth. The Zeelandia sailed alongside the English warship and fired three broadsides into the frigate. Only able to fire one gun in reply, the Elizabeth surrendered. Captain Lightfoot was not with his ship, despite having prior knowledge of the Dutch fleet’s entrance into the bay. Rather, he chose to attend a wedding with a wench he had brought with him from England.

Once the Zeelandia made a wreck of the Elizabeth, the other Dutch ships captured 19 tobacco ships. Crimson now had to decide which vessels he could take back to the Netherlands. The Dutch admiral just did not have enough men to operate all of the captured vessels. So, he burned six ships and prepared 13 to leave the Chesapeake with his fleet. But before he could depart, he needed to obtain fresh water. Crimson’s men made several landings; yet each time they were repulsed by the Virginia militia.

On June 8, the Dutch attacked Old Point Comfort. During that engagement, Colonel Miles Cary, a member of the Governor’s Council, was mortally wounded and died two days later. The Dutch still had to remain in Virginia waters to secure water.

Berkeley Strives to Strike Back

Governor Berkeley was distressed over these sad events and was determined to gain revenge and recapture some of the tobacco transports. He knew that the Dutch could sail up to Jamestown and destroy the capital of Virginia. Therefore, Berkeley decided to arm the nine York River tobacco ships. These vessels, along with the three ships that had escaped to Jamestown, would attack Crimson’s fleet in a double envelopment movement. Lightfoot volunteered his services as well as that of his crew. The governor also mustered more than 900 men, in three regiments, to help man the tobacco ships. Everyone involved appeared to approve the plan.

Berkeley planned to command the entire force. Yet, there were so many delays, that the assault was never launched. On June 11, 1667, Crimson’s command and its prizes left the Chesapeake to return to the Netherlands. The Dutch raids had been disastrous for Virginia and these losses were only compounded when a hurricane struck the colony with devastating effect on August 27, 1667. It had been an awfully bad year for Virginia!

Third Anglo-Dutch Naval War

The Second Anglo-Dutch naval conflict was a tremendous humiliation for England. The next war was not necessarily associated with trade. Rather it was connected to King Charles II’s secret alliance with King Louis XIV of France and was intended to isolate the Dutch provinces and conquer the Spanish Netherlands. King Charles needed the French subsidies to circumvent Parliament. Even though the French secured some initial land victories, the combined Anglo-French fleet was defeated in several engagements which helped to save the Dutch from defeat.

Virginia Prepares

The August 27, 1667 hurricane had completely destroyed the fort at Old Point Comfort. This enabled Governor Berkeley to move forward with concepts of Virginia’s coastal defense. So, he advanced, at least in theory, to fortify Jamestown, Tyndall’s Point on the York River, Corrotoman on the Rappahannock River, and a bluff at the mouth of the Nansemond River. All of these forts were either poorly constructed or were never begun. They lacked cannons, ammunition, soldiers, and skilled construction workers. The Virginians had certainly forgotten the lessons of the Dutch invasions of 1667.

Guard Ships Required, Requested, and Readied

When the Third Anglo-Dutch Naval War erupted in Europe, Governor Sir William Berkeley once again pleaded to have guardships sent to protect and escort to England all of the tobacco transports assembling in the lower Chesapeake Bay. England immediately consented with a pair of frigates. The two 50-gun warships that arrived in Spring 1673 were Barnaby, commanded by Captain Thomas Gardiner, and Augustine, commanded by Captain Edward Cotterell. This made the Virginia governor feel somewhat relieved. Unfortunately, these ships were not quite as powerful as they appeared and needed repairs and supplies. Most of the tobacco ships; nevertheless, had already arrived in the lower James River and were ready for the escorts to take them to England.

Governor Berkeley received intelligence in late April that a Dutch force intended to soon attack Virginia. He considered calling out the militia to place 50 soldiers on each transport, waiting until those ships could safely leave the Chesapeake. Yet, Berkeley feared Indian attacks and possible slave uprisings (the first slave revolt in Virginia was on September 1, 1663, in Gloucester County). He was also unsure of the militia’s combat readiness or if the troops had the capability of manning the unfinished forts. The governor knew that the Dutch would soon return to Virginia.

Another Unwelcome Visit

Two different United Provinces forces were ordered to the South Atlantic and Caribbean to harass English shipping. One was commanded by Vice-Admiral Cornelius Eversten the Youngest, and the other by Admiral Jacob Binkes. Both men had served with distinction during the Second Anglo-Dutch Naval War. Eversten had actually been given command of England’s captured great ship, Royal Charles, captured during the raid on the Medway. Both of these officers had separate, but similar orders to intercept the homeward bound English East India Convoy.

They were interrupted in their tasks as they came upon a larger English squadron and went to the Caribbean instead. There, Eversten and Binkes would join commands. Together they captured the island of St. Eustatia on June 8, 1673. Believing that they had achieved enough in the Caribbean, the powerful Dutch squadron steered toward the Chesapeake Bay. The Dutch entered Virginia waters on July 11, 1673, and anchored in Lynnhaven Roads.

Coastwatchers sent word to Jamestown that a fleet of eight ships had entered the Chesapeake. The Dutch squadron included the 46-gun flagship Swanenburgh and seven other warships. When news arrived of the enemy’s arrival, it was decided that the English would maintain a defensive posture using the Augustine and Barnaby along with six large, well-armed merchant ships. The thought was that if the Dutch chose to attack the tobacco fleet, the English were well prepared to hold off the dangerous enemy.

The Battle is Joined

While this seemed to be a good defensive plan, the eight-ship Maryland fleet was observed coming down the bay heading directly toward Eversten’s squadron. Therefore, on the morning of July 12, the English were forced to quickly act to save the Maryland transports. Capt. Gardiner of the Barnaby took decisive action and, with Capt. Cotterell, decided to attack the Dutch in an effort to engage the enemy. The small squadron sailed out of Hampton Roads to draw the enemy toward Hampton. En route, four merchantmen ran aground, while a fifth retreated toward the James River. As this force neared the Dutch, the sixth tobacco transport, captained by a man named Groves, turned away to avoid the engagement.

Nevertheless, the two English warships sailed directly toward the Swanenburgh and raked the Dutch warship with a heavy broadside. As Gardiner changed course back toward Hampton Roads, a running battle ensued between the Dutch ships and the Barnaby. In doing so, Barnaby blocked the wind from the Dutch squadron. For more than an hour, Gardiner fought Swanenburgh with great zeal and with no support from the Augustine. Captain Cotterell did not take advantage of his firing position and fled toward the mouth of the Elizabeth River. Darkness shrouded Hampton Roads and the battle ended when Swanenburgh ran aground.

The Barnaby had suffered serious damage to its masts and rigging, Gardiner had saved the day for almost all of the tobacco transports, While the battle raged, the Maryland tobacco fleet was able to slip past the Chesapeake Capes with the loss of only one vessel. Simultaneously with the engagement, 22 tobacco ships escaped up the James River toward Jamestown; about 12 merchantmen found protection within the Nansemond River. The Barnaby had indeed achieved victory from the jaws of defeat.

Eversten and Binkes seemed to have trapped the tobacco fleet; however, they just could not get at those merchantmen. That evening, Binkes captured Grove’s grounded merchantman and a tobacco shallop coming down the bay. The next day, July 13, the Dutch did not wish to try to sail into the uncharted waters of the Elizabeth and Nansemond rivers for fear that they would run aground on a shoal. As Eversten and Binkes considered their options to attack the nearby warships and tobacco ships, Eversten sent three vessels — Zeehond, Schaeckerloo, and Captain Boes’s shallop — into the James River where they came upon five tobacco transports that had not made it to the protection of Jamestown. All had been grounded on shoals and four were burned as they were soundly stuck in the sand. The Madras was freed and taken back down river to the Dutch fleet’s anchorage.

Off to New York

By now, the Dutch had been in the bay for five days and had captured several ships; however, they were unable to capture or destroy the rest of the tobacco fleet. Gleaning information from a captured vessel, they learned that New York (which nine years before was known as New Amsterdam) was poorly defended. So, the Dutchmen left the bay with their prizes. Sailing north, they reached New York in August 1673 and recaptured the town for the United Provinces. Eversten and Binkes then returned to the Netherlands with news of their victories.

Aftermath

Once the Dutch left the Chesapeake, the Nansemond River and James River tobacco fleets joined up with the Rappahannock and York rivers tobacco convoy. These combined fleets, escorted by the Barnaby and Augustine, set sail for England on August 10, 1673. They arrived safely, helping to revitalize the Maryland and Virginia economies. In the meantime, Berkeley endeavored to finish the construction of his planned forts so as to give the Virginians a stronger sense of security against another Dutch raid. The 1667 Dutch attack had damaged the Virginia economy in such a manner that it did not recover until the end of the Third Anglo-Dutch War. Resolute action during the 1673 raid by the English guardships had saved the colony from yet another disaster.

The English citizenry had become dis-illusioned with the war and England’s ally, France. Consequently, the Third Anglo-Dutch Naval War ended on February 17, 1674, by the Treaty of Westminster. One of the treaty’s terms entailed that the English would return Suriname to the Netherlands and receive New York in exchange. Somehow the Dutch believed that Suriname was more valuable than the city on New York Bay!

Virginia was not to be invaded by sea again for over a hundred years. Several forts would be constructed again on Old Point Comfort, all of which were destroyed by hurricanes. Then in 1779, Virginia’s former royal masters invaded the lower Chesapeake only to be defeated by the new United States and its ally, France. The British would return in 1813 and 1814; however, in the aftermath of the War of 1812, the young nation would build significant fortifications defending Hampton Roads on Old Point Comfort and Rip Rap Shoal. Both forts still stand today, echoes of past conflicts.

NOTE

{1} Christopher Hill, The Century of Revolution: 1603-1714. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1980, p.181.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Crutchfield, James A. The Grand Adventure: A Year by Year History of Virginia. Richmond, Virginia: The Dietz Press, 2005.

Dabney, Virginius. Virginia: The New Dominion. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc.,1971.

Hill, Christopher. The Century of Revolution: 1603-1714. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1980.

Lockyer, Roger. Tudor and Stuart Britain. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1964.

Quarstein, John V. A History of Ironclads. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2007.

____ and Rouse, Parke S. Jr. Newport News: A Centennial History. Newport News, Virginia: City of Newport News, 1996.

Salmon, Emily J. and Campbell, Edward D.C. The Hornbook of Virginia History: A Ready Reference to the Old Dominion’s Peoples, Places, and Past, 4th Edition. Richmond, Virginia: Library of Virginia, 1994.

Shomate, Donald G. Pirates on the Chesapeake. Centreville, Maryland: Tidewater Publishers, 1985.

____ and Haslach, R.O. Raid on America: The Dutch Naval Campaign of 1672-74. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2002.