When President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a blockade of the entire southern coastline, the US Navy only had 93 warships, and almost half of these were outdated or unusable. So, the US Navy went on a buying spree purchasing every steamer that could mount cannons. One of these vessels was the St. Mary which was soon commissioned as USS Hatteras. In turn, the Confederacy did not have a navy and sought to obtain ships overseas to attack Northern merchant ships. The most successful of these commerce raiders was CSS Alabama. These two warships would have a fatal encounter on January 11, 1863, off Galveston, Texas, resulting in the sinking of USS Hatteras.

From the Steamer St. Mary to USS Hatteras

The St. Mary was built by Harlan and Hollingsworth of Wilmington, Delaware. Shortly after this iron-hulled steamer’s launching, St. Mary was purchased by the US Navy on September 25, 1861. The ship was then fitted out at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and commissioned in October 1861 as USS Hatteras. [1]

The vessel’s general characteristics were as follows:

Displacement: 1,126 tons

Length: 210 ft.

Beam: 34 ft.

Draft: 18 ft.

Machinery: iron side wheels, one condensing beam engine, one boiler, 500HP

Speed: 8 knots

Compliment: 110

The sidewheeler had little room for armament; however, Hatteras did mount four x 32-pounder shell guns and one x 20-pounder rifle. [2]

Into Service

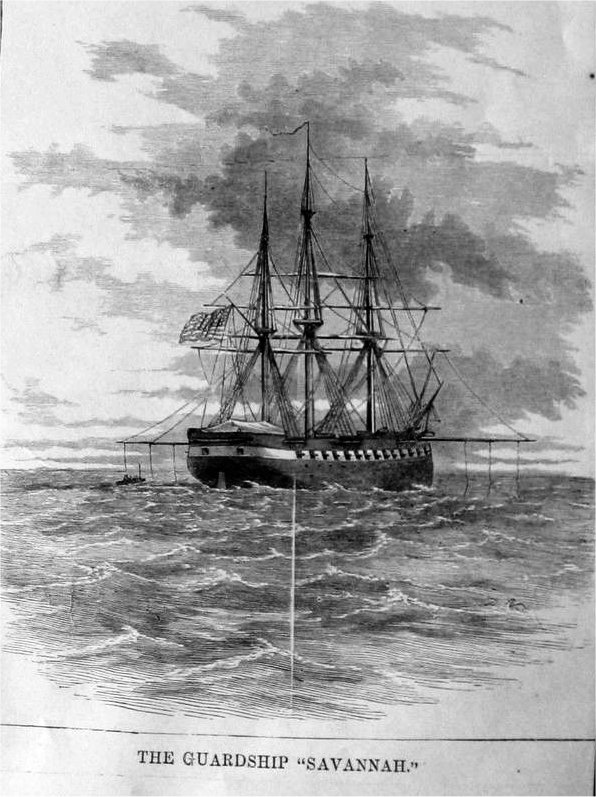

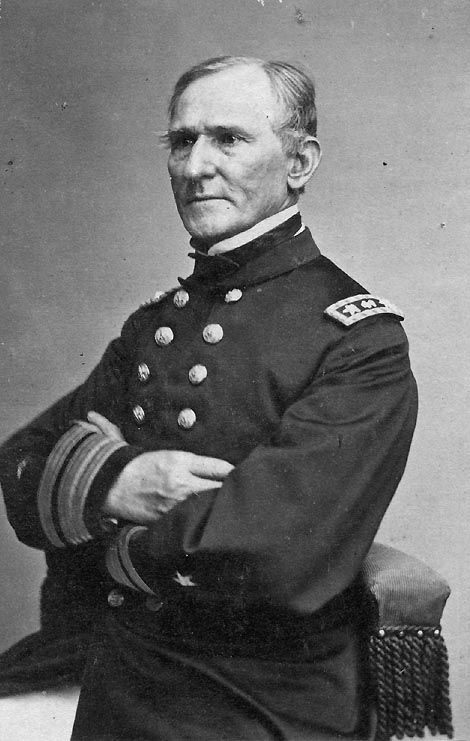

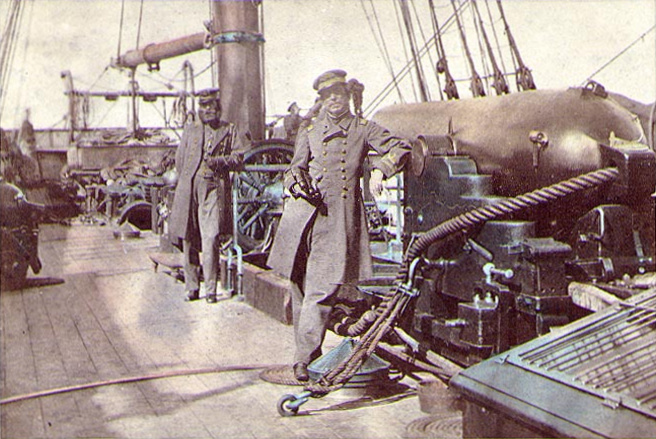

Commander George Foster Emmons was detailed to command USS Hatteras. Emmons had joined the US Navy in 1828 and participated in Captain Charles Wilkes’s Exploring Expedition which discovered the Antarctic continent. He served on USS Ohio and USS Warren, fighting in California during the Mexican War. Emmons later commanded the frigate USS Savannah. He was described as an “officer of the old school, and while scrupulously polite … he rigidly enforced every detail of regulation.” [ 3]

The Hatteras was ordered to join the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron; the warship arrived at Key West, Florida, on November 13. Reassigned to the Gulf Coast Squadron in early January 1862, the steamer blockaded Apalachicola, Florida, until being sent to guard Cedar Key, Florida, arriving there on January 7, 1862.

Nine days later, Hatteras completed a successful raid on the town. Marines and sailors landed and destroyed a Confederate battery and several Confederate soldiers were captured. The Federals burned seven schooners containing cotton and turpentine, destroyed the Florida Railroad’s wharf, tracks, and rolling stock, and the Cedar Key telegraph office. [ 4]

Success as a Blockader

Once again, Hatteras was reassigned to blockade duty off Vermillion Bay, Louisiana. As soon as the paddler arrived off Berwick, Louisiana, Hatteras fought a brief engagement with the gunboat CSS Mobile on January 26, 1862, in Atchafalaya Bay. The Mobile was originally built in Philadelphia however, the Confederate Navy assumed control of the vessel when Louisiana left the Union. While this sidewheeler was partially built of wood and iron, and armed with five guns, including an VIII-inch shell gun, Mobile was overmatched by Hatteras and escaped, thanks to its shallow draft of 13 ft. [5]

Even though this prey escaped, Hatteras enjoyed tremendous success as a blockader in the Gulf of Mexico. From January to December 1862, Emmons’s ship captured 10 blockade runners. On two different occasions Hatteras captured two runners a day: the steamer PC Wallis and schooner Resolution on April 4, as well as the steamers Fashion and Governor Mounton on May 6, 1862. [6]

Captain Emmons was replaced as captain of Hatteras by Lt. Commander Homer Crane Blake in November 1862. Blake joined the US Navy on March 2, 1840, and eventually graduated from the US Naval Academy with the rank of passed midshipman on July 12, 1846. One of his most important duties prior to the Civil War was his supervision of the construction of USS Merrimack at Charlestown Navy Yard. [7]

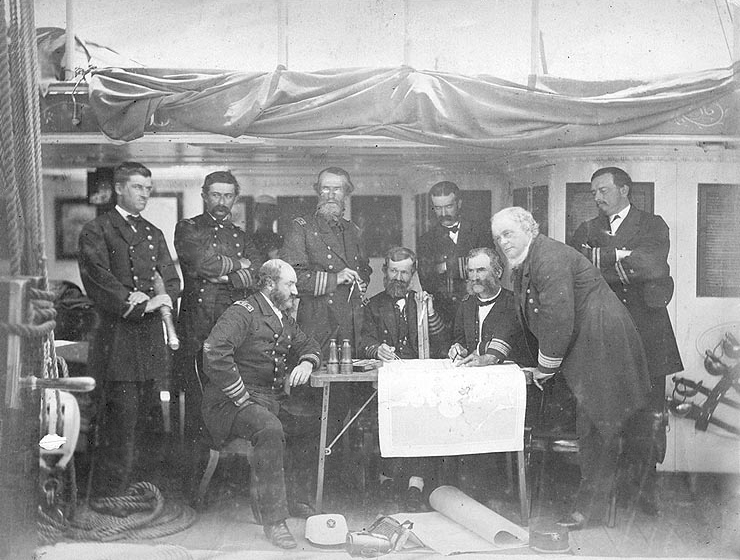

On to Galveston

The Hatteras was detailed to Rear Adm. David G. Farragut’s West Coast Blockading Squadron. The flotilla off Galveston was managed by Farragut’s fleet captain, Commodore Henry H. Bell. Blake’s warship arrived off Galveston on January 6, 1863, joining four other warships. Bell knew that Blake’s in-depth knowledge of Galveston Bay would be useful as the Hatteras’s commander had worked on the coastal survey of the bay and its approaches from 1848 to 1850. The flotilla was stationed there as the Union was planning a joint operation to capture Sabine Pass. On January 11, 1863, the Federal squadron noted a set of sails just over the horizon. Commodore Bell, in the USS Brooklyn, ordered the Hatteras to give chase and investigate the ship at 3:00 p.m. [8]

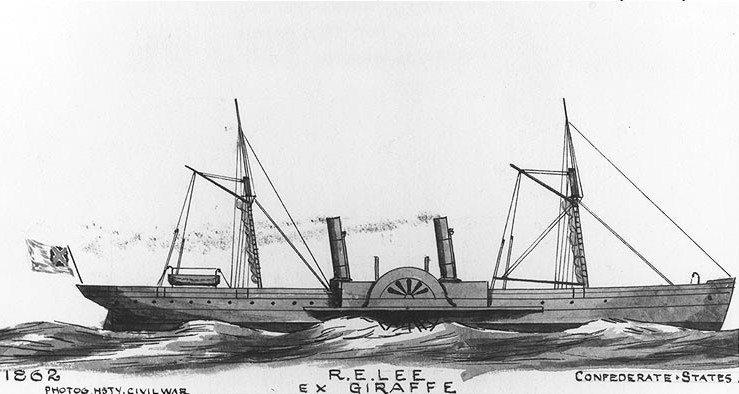

Enter CSS Alabama

The USS Hatteras’s prey was a much more powerful ship known as CSS Alabama. This commerce raider was built in secrecy by John Laird Sons and Company of Birkenhead as Hull No. 290. Commander James Bulloch was the Confederate Navy’s agent in Great Britain, detailed to procure ships for the Confederacy. He had planned for the construction of this bark rigged steam screw sloop of war. When the ship was launched on May 14, 1862, it was named Enrica. The vessel slipped out of Liverpool on July 29, 1862; destination: the Azores. [9]

Although Enrica did not appear at first to be a warship (it was not armed), the sloop was constructed to be one. The decks had been reinforced to support heavy artillery and its magazine was installed beneath the waterline. The sloop was 220 ft. in length, with a beam of 31.9 ft., and a draft of 17.8 ft. Enrica had two x 300 HP horizontal steam engines with one screw propeller. The ship could make 13 knots. [10]

Semmes on the Scene

On August 20, 1862, Enrica arrived in Terceira Bay, Azores. The vessel met the supply ship Agrippina, and the steamer Bahama which had on board James Bulloch, Raphael Semmes, and two dozen Confederate naval officers. Semmes had already gathered great fame as the commander of the first Confederate commerce raider, CSS Sumter. Immediately, the crews began the transfer of coal, supplies, and armaments . The soon-to-be-commissioned CSS Alabama battery would consist of six x 32-pounder shell guns in broadside, as well as one x 110-pounder Blakeley rifle, and one x 68-pounder Blakeley shell gun as pivot guns. [11]

Once all was in order, Semmes arranged for Agrippina to rendezvous with his ship for resupply. Alabama was then commissioned on August 24, 1864, and as the Confederate banner rose up the staff, the band played “Dixie.” The crew, mostly British, were recruited with the offer of signing money and wages paid in gold. They gave three “hurrahs!” as the cruise began. Alabama then sailed off into the night with the stars shining, and a bright comet was seen off to the north. Alabama would quickly capture and burn its first victim, a whaler named Ocmulgee. [12]

A Fateful Encounter

The commerce raider sailed across the North Atlantic and into the West Indies and on into the Gulf of Mexico. By January 1,1863, Alabama had already captured 26 prizes. [13] Semmes had learned that the Union was planning a joint operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, to capture Sabine Pass, and he expected to capture several transports near Galveston, Texas.

The circumstance had changed before Semmes arrived since Maj. Gen. John Bankhead Magruder had liberated Galveston on New Year’s Day, 1863. Unbeknownst to Semmes, instead of transports he recognized, there were five blockaders off the entrance to Galveston Bay. Alabama‘s commander knew he could not battle with this squadron. Instead, he sailed along the horizon to tempt one of the blockers to follow him. Well, USS Hatteras took the bait.

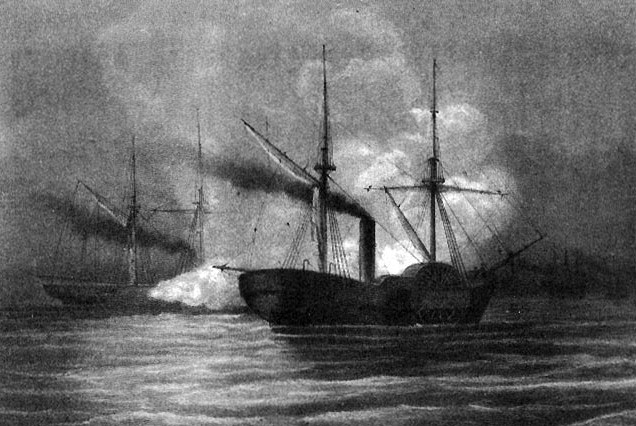

As soon as Hatteras gave chase, Semmes slowed his sloop of war so that the Union blockader would soon get in range of Alabama’s heavy battery. Blake noted that as he continued the chase, he “rapidly gained upon the suspicious vessel. Knowing the slow rate of speed of the Hatteras, I at once suspected that deception was being practised.” [14] The steamer’s commander now realized that the unknown vessel was probably the already infamous Alabama which was in Blake’s path with its broadside facing his ship. Blake cleared his vessel for action and worked four guns onto one side of Hatteras.

It was now about 7:00 p.m. and darkness shrouded the scene. When the blockader reached within 75 yards of Alabama, Blake hailed, “What steamer is that?” The answer was returned: “her Britannic Majesty’s ship Vixen!” [15] The Union commander replied that he would send a boat over. Both ships began to maneuver; however, the Confederate steamer placed itself in a position to rake Hatteras. [16]

Just as the cutter pulled away from Hatteras, Capt. Semmes shouted, just as the Confederate flag was being hoisted, “We are the Confederate steamer Alabama!”, which was quickly followed by a broadside that crashed into Hatteras causing considerable damage. Semmes recounted that “my men handled their pieces with great spirit and commendable coolness, and the action was sharp and exciting while it lasted, which, however, was not very long, for in just thirteen minutes after firing the first gun, the enemy hoisted a light and fired an off-gun, as a signal that he had been beaten.” [17]

Blake steamed Hatteras within 30 yards of Alabama in an attempt to board the Confederate steamer. Pistol and musket shots were exchanged; however, Hatteras could not close with the Alabama as shells from that ship rumbled through the Union steamer causing considerable damage. One shell entered amidship in the hold, setting fire to it; another shell passed through the sick bay, exploding in an adjoining compartment, creating a fire; and yet another shot made it into the engine room and broke the cylinder head, sending steam throughout the vessel. This shot left Hatteras helpless, unable to work its pumps or for the steamer to maneuver. The Union vessel was dead in the water in a sinking condition.

Commander Blake stated in his report “the vessel on fire in two places, and beyond human power a hopeless wreck upon the water, with her walking beam shot away and her engine rendered useless.”[18] Blake maintained his fire with the hope of disabling Alabama, hoping that the sound of distant gunfire would bring other ships of the squadron to the battle scene.

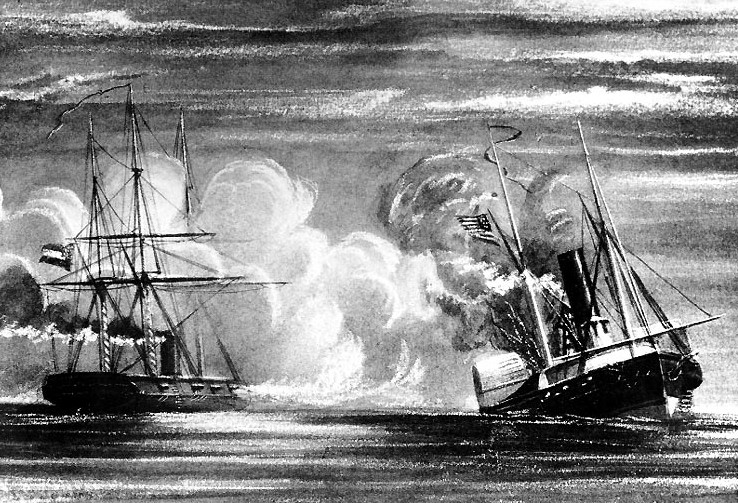

The Hatteras is No More

The commander of Hatteras had run out of options. He had just been told that shells had entered the “Hatteras at the water line, tearing off entire sheets of iron, and that the water was rushing in … Learning this melancholy truth … I felt that I had no right of sacrifice uselessly, and without any desirable result, the lives of all under my command.” [19] When Hatteras surrendered, Alabama sent boats to render assistance and saved most of the crew. Hatteras’s losses included two killed and five wounded. In turn, Alabama suffered two wounded.

Semmes then took the officers and men of the sunken Union warship to Jamaica where they were paroled. Hearing the sounds of the engagement and seeing flashes in the distance, Commodore Bell took USS Brooklyn out to investigate the action. The sloop of war arrived on the scene in the early morning hours of January 12, only to discover the hulk of Hatteras upright in the water about 20 miles south of Galveston Light. Bell noted that only the masts of Hatteras reached out of the water and from the topmast, the US Navy commissioning pennant was still flying. Hatteras had surely lived up to the motto, “Sink Before Surrender.”

After Action Report

Commander Homer C. Blake wrote his battle report to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles from Jamaica. He recounted his version of the engagement and in conclusion, he lauded several of his officers and crew members: “I desire to refer to the efficient active manner in which Acting Master Henry Porter, executive officer, performed his duty. The conduct of assistant Surgeon Edward S. Matthews demands my unqualified commendation. I would also bring favorable notice of … Acting Master’s Mate F.J. McGrath, temporarily performing duties as gunner. Owing to the darkness of the night … I am only able to refer to the conduct of these officers…. To the men of the Hatteras I cannot give too much praise. Their enthusiasm and bravery was of the highest order.” [20]

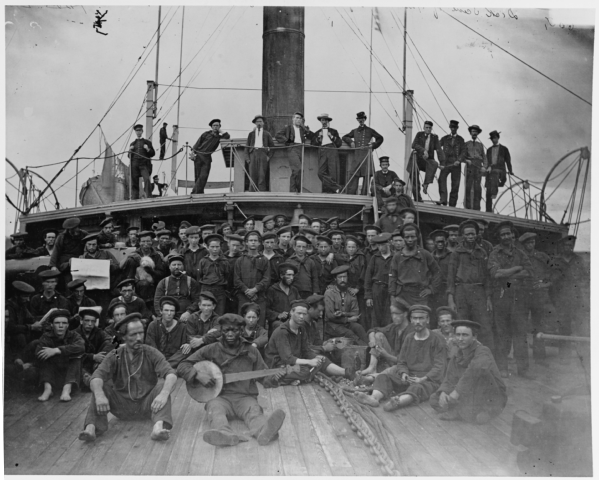

African Americans Aboard USS Hatteras

After the war, Blake wrote about several overlooked members of the crew who performed heroic actions of the highest order during the battle. “During those terrible moments,” the commander of Hatteras remembered, ”the ship was on fire, and shells were tearing through her sides and exploding with awful destruction, when the engine was destroyed, and the engine room and deck enveloped with scalding steam, the steward of the ship, a colored man, performed an act of calm and deliberate heroism which should place his name very high upon the roll of honor. Under the passageway there was stored a large quantity of small arms and ammunition. As shell after shell exploded, setting the light material on fire, the room became extremely hot and filled with smoke. The order had been given to ‘drown the magazine.’ The steward remained unflinchingly at his post, dashing water upon the ammunition until the close of the action. When asked if he did not find his position rather warm and dangerous, he relied: ‘Yes, but I knew that if the fire got to the powder, the gentlemen would get a grand hoist.’ “ [21]

Blake also noted the brave actions of another African American crew member. Unfortunately, he did not record the names of these individuals. The heroic steward was most likely either First Class Boy John Cormick (Cornish) or First Class Boy Edward Matthews. The other African American member of the crew was Landsman Fortuno Gomes. Nothing else is known about these individuals. (A Landsman is the lowest professional rank on a ship, given to new recruits with little or no experience at sea. Boys were crew members with little experience at sea — regardless of age — who performed critical duties as runners, carrying powder or messages in battle. The lowest rank within that rating was Third Class Boy, and the highest was First Class Boy. Boys might also serve as stewards, serving meals to officers when not in battle.) [22]

African Americans had not been limited by their race to join the US Navy since the Revolutionary War. The Civil War was no different and, in fact, may have had greater Black enlistment than any other prior war. As many as 10 to 30 percent of some ship’s crew were of African descent. As many as eight African Americans served aboard USS Monitor, comprising more than 10 percent of the crew. Black enlistment was high in the US Navy, especially after the Contraband of War Decision since African Americans were not allowed to serve in the army until after 1863’s Emancipation Proclamation and Militia Act.

Gershon Jacques Henry Van Brunt, commander of USS Minnesota, noted that all of the Black sailors serving on that frigate during the Battle of Hampton Roads received special praise. Van Brunt wrote that the “Negroes fought energetically and bravely — none more so. They evidently felt that they were working out the deliverance of their race.” [23]

Revenge the Hatteras

Once CSS Alabama left the Union sailors in Jamaica, the commerce raider continued on its spree of destruction. This cruiser was the most successful of all Confederate commerce raiders, capturing or burning 65 Northern merchant ships. Numerous Federal warships, like USS Wyoming, were searching for Alabama.

Needing repairs, the Confederate cruiser put into Cherbourg, France. There the raider was trapped by the Union sloop of war, USS Kearsarge. Alabama came out of the French harbor to engage Kearsarge on June 19, 1864. This was Semmes’s second battle with a Union warship; however, the result would be far different than the engagement with Hatteras. The Alabama would be sunk that day.

NOTES 1 Paul H. Silverstone, Civil War Navies 1855-1883, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2001, 51. 2 Ibid. 3 ”USS Emmons,” Destroyer History Foundation online, accessed September 2, 2020.http://destroyerhistory.org/benson-gleavesclass/ns_emmons/ 4 Naval History Division, Civil War Naval Chronology: 1861-1865, Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1971, II-7. 5 Silverstone, 172. 6 Ibid, 51. 7 “Commodore Homer Blake Dead,” New York Times, January 22, 1880. 8 Civil War Naval Chronology, III-8. 9 Douglas H. Maynard, “Plotting the Escape of the Alabama,” Journal of Southern History 20 (1954), 197. 10 Silverstone, 158. 11 Ibid. 12 Official Record of the War of the Rebellion, Navies (Hereafter referred to as ORN), Ser. I, I:776-783. 13 Silverstone, 158. 14 Author’s explanatory note: There is some confusion as to what ship name Semmes shouted to Blake just before the battle began. Blake noted in his official report that he heard the unknown ship to be called HMS Vixen (ORN, Ser. I, 2:18), whereas Semmes recounted that he called the Alabama the HMS Petrel (ORN, Ser.1,1:778). 15 ORN, Ser.I,2:18. 16 Ibid. 17 Civil War Chronology, III-8 18 ORN, Ser.1,1:18 19 Ibid. 20 Ibid. 21 John S. C. Abbott, “Heroic Deeds of Heroic Men,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine,September 1866, Vol 33, Issue 196, 458. 22 “Mystery Aboard the USS Hatteras,” National Marine Sanctuaries online, accessed September 2, 2020. https://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/news/feb16/mystery-aboard-the-uss-hatteras.html 23 ORN, ser. I,7: 12-13. BIBLIOGRAPHY Abbott, John S. C. “ Heroic Deeds of Heroic Man.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Volume 33, Issue 196, September 1866. Civil War Naval Chronology 1861-1865. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, Navy History Division, 1971. Luraghi, Raimondo. A History of the Confederate Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1996. Maynard, Douglas H. ”Plotting the Escape of the Alabama.” Journal of Southern History, no.20 (1954), Rice University, Houston, Texas. “Mystery Aboard the USS Hatteras.” National Marine Sanctuaries online. Accessed September 2, 2020. https://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/feb 16/mystery-aboard-the-uss-hatteras.html Official Record of the War of the Rebellion, Navies. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1881 - 1904. Ramold, Steven J. Slaves Sailors Citizens: African Americans in the Union Navy. DeKalb, Illinois: University Press, 2002. Scharf, J. Thomas. History of the Confederate Navy. New York: Gramercy Books.1996. Silverstone, Paul H. Civil War Navies 1855-1883. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2001. “USS Emmons.”DestroyerHistoryFoundationonline. Accessed September 2,2020. http://destroyerhistory.org?benson-gleaves class__emmons/