Welcome to the second installment of our miniseries on no. 3746, a Nishimura-style Japanese midget submarine. We’re deep diving into an on-going project to resupport this one-of-a-kind vessel. Check out the first post in the series to learn about no. 3746’s history and how it arrived at the Museum.

The purpose of the project is to lift the sub onto a custom cradle and move it to a more accessible location. The sub currently rests on its keel and is supported by several blocks. A proper support will protect the hull, provide safe access, and bonus, can be used as an exhibit mount when the time comes to display it!

Before lifting the sub, we needed to assess its current condition and identify potential issues. In order to answer these questions and take measurements it was necessary to climb inside. I love my job, but some days I really love my job!

We took the normal safety precautions when we entered in February. We wore Tyvek suits and respirators to make sure we didn’t come in contact with potentially harmful materials. Since the submarine was built in 1940, it is probable that the paint inside is lead-based. We also left the hatch open for 24 hours to vent the inside and used an air meter to confirm that the environment was safe. Years ago the museum staff cut a hole in the stern to provide ventilation, so we anticipated that there wouldn’t be an issue. Lastly, we built a custom ladder so we could climb in and out without using the original rungs.

There was a moment of panic when we realized how small the hatch was, but luckily both Will and I fit. The trick is to put your arms over your head. Thankfully neither of us is claustrophobic!

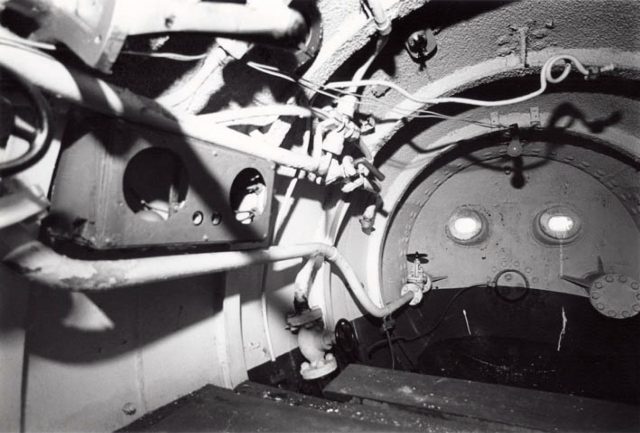

We weren’t sure what we’d find inside. We have photographs from after the sub arrived in 1946, however no one’s entered the sub in 30 years. And while museum staff painted the outside several times, little was done inside. We do know that when the Allies took control of the sub they removed much of the interior; gauges, steering equipment, even the batteries. The engine and ballast tanks are the main surviving features.

Let’s look at how it’s changed over 70 years:

The paint in the cockpit is flaking and loose. This is due to restricted air flow and humidity fluctuations. Interestingly, there are three distinct paint schemes; bumpy white, flat white, and red. The flat white appears to have suffered the most. Several paint layers are visible under these top coats as well. Samples were taken for analysis to learn more about their composition. Notice the missing gauges in the 1950s photo.

Looking back towards the engines, we see that the hull is sound. There is a large amount of corrosion along the ballast tanks, however this does not affect the superstructure. You can see in the early picture, that this is an on-going problem and likely from the pipes used to fill the tanks. The addition of chlorides, from saltwater ballast in the 1940s, exacerbated the situation. The batteries sat in well between the tanks.

The engine is a thing of beauty. It is in excellent condition, as is the hull paint in the aft section of the vessel. This is partially due to the ventilation hole cut in the hull which allowed more air circulation than in the bow. You can still see the passage of time on the white painted pipe entering the engine which has peeled severely in 70 years.

At 80 years old, no. 3746 is in good condition inside and out. The only major concern is the keel, which has been resting on the ground for decades and is unstable. Next time in “the Land of Submarines” we’ll talk about these concerns and what we’ve done to thoroughly document the keel to prepare for lifting.