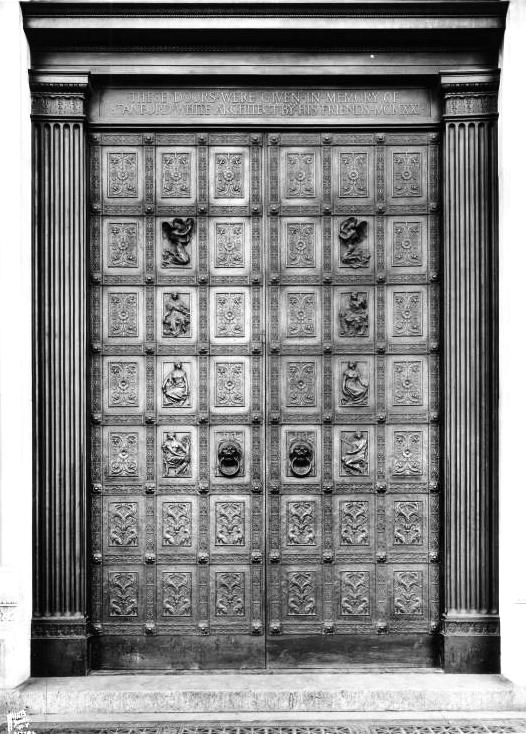

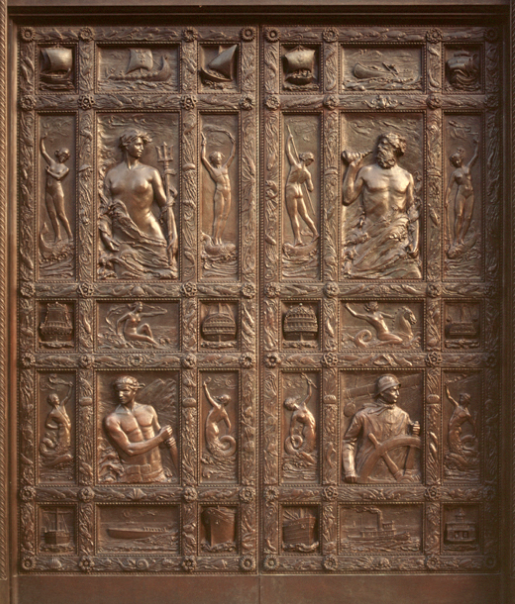

Have you ever noticed the big metal doors at the Business Entrance of The Mariners’ Museum and Park? Have you ever thought that maybe they were a little fancy for an entrance where deliveries are made and staff enters to gather our badges and trek to wherever our offices happen to be on-site? Well, those doors, made of bronze, are actually part of our Collection and used to be the Main Entrance to the Museum!

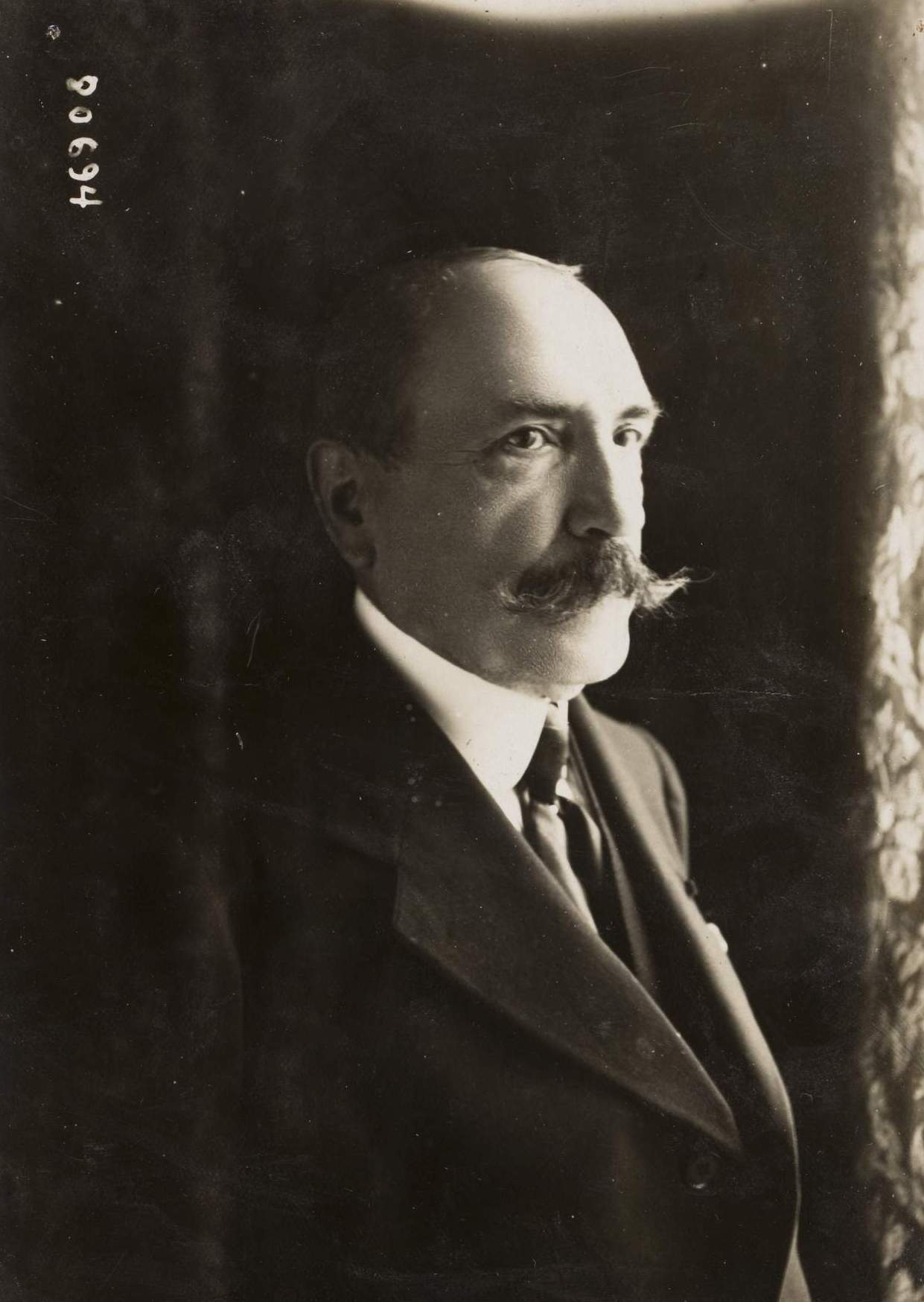

There is a bit of a story behind them. As you have probably read in a previous blog, Archer M. Huntington was the driving force behind the construction of The Mariners’ Museum and Park. It was his vision to have a stunning entrance to the Museum, something that would visually make people stop and say “WOW!”. Incidentally, this is why the original portion of the Museum has the very unusual “Huntington Squeeze” brick and mortar technique. It’s done by not scraping off the mortar as layers of bricks are added in the wall construction.

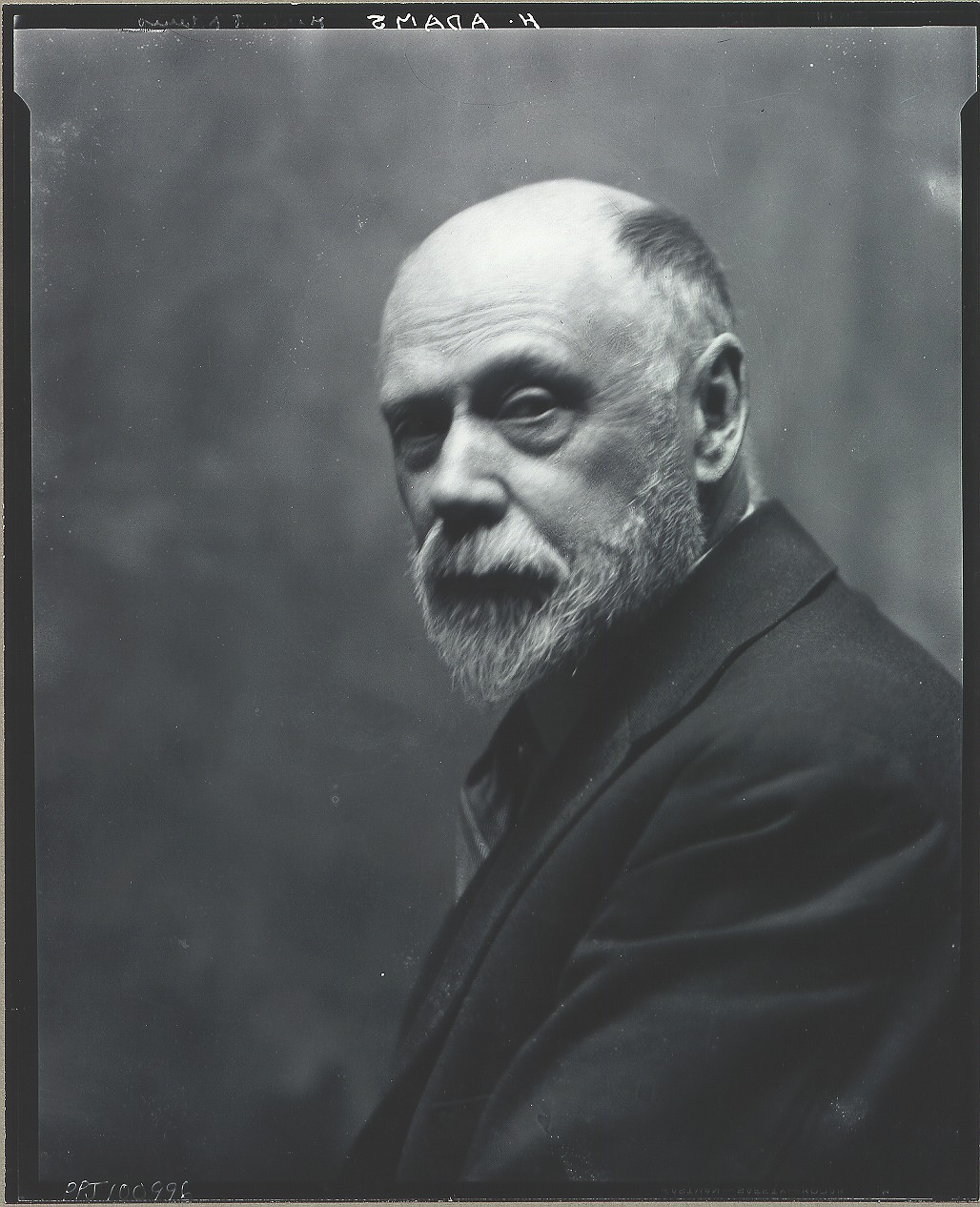

Archer really liked it and used the style often at many of his homes and museums. I’m sure constructing it made brick mason’s cringe. Anyway, he wanted some really impressive doors for his new Museum. So where did he turn? To his longtime friend, Herbert Adams, professional and very successful sculptor extraordinaire.

Samuel Herbert Adams was born in 1858 in West Concord, Massachusetts. At the young age of five, his family moved to Fitchburg, Massachusetts so his father could take a job at the Putnam Machine Company. He attended public school and was inspired by his first art teacher to pursue a career in art. Adams attended the Massachusetts Normal School in Boston and earned a teaching certificate. He taught from 1878 until 1882 Deciding this was not the best use of his time or talent, he left for Paris, France. From 1885 until 1890 he studied art with Antonin Mercié.

In 1889 private funds were donated for an ornamental fountain to be built in the “town square” in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, Adams’ home town. This 26-foot diameter granite and bronze fountain showing two playful boys and a family of turtles was the first public commission awarded to Adams and was created in his Paris studio. This was the first, large sculpture, done in the “lost-wax” process, brought to America. Below is a video from the National Sculpture Society (yes, Adams was a member) about the “Lost Wax Casting Process”.

This was a banner year for Herbert Adams (he didn’t use his first name of Samuel) as this was also the year that he married his wife, Adeline Valentine Pond. Isn’t that just a lovely name? Ironically she grew up in Boston, Massachusetts, but they found one another in Paris! They met in 1887 when she posed for a marble bust that ended up being exhibited at the Chicago’s World Fair in 1893.

She inspired her husband to use a new technique of polychrome busts and tinted marbles. It was very new and cutting edge.

Interestingly enough, they both attended the Massachusetts Normal School in Boston. Basically, it was a college to prep students to become teachers. Although only a year apart, he started at 18 and Adeline started at age 21. She was an artist in her own right but was also a huge advocate for female sculptors, including Anna Hyatt Huntington (our Museum’s benefactor). She also advocated for war memorials to be created with purpose by professional artists, instead of being mass-produced in factories.

Adeline wrote seven books, including The Spirit of American Sculpture; Daniel Chester French, Sculptor; Childe Hassam: John Quincy Adams Ward: An Appreciation; Sylvia: An Exhibition of American Sculpture; and “Our medals and Our Medals.” And yes, the publication really does have a lower case “m” in the title. Annoying, I know. She also wrote quite a bit of poetry including two collections about her deceased daughters, Mary and Sylvia, both of whom died in infancy.

Basically, what we have here is an artistic power couple who moved in creative, cultured circles. They began spending summers at the Cornish Artists’ Colony in Cornish, New Hampshire, in the late 1890s. Artists’ Colony? Well, the image below is just the sort of thing that comes to mind when one says “Artists’ Colony”, am I right?

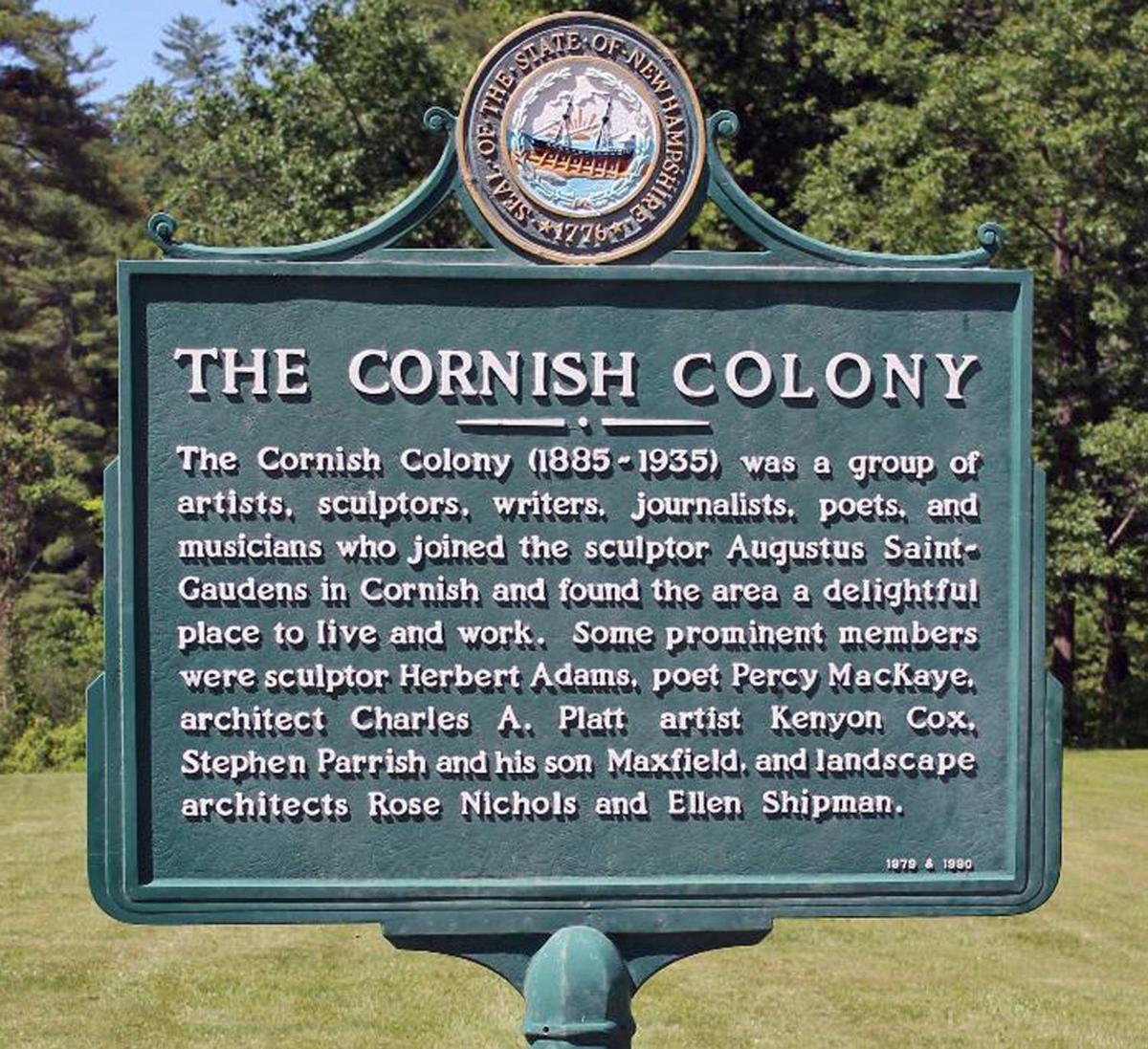

And that really is part of it. The Cornish Artists’ Colony was one of the more popular places for creative fine art activity in the eastern United States. Between, 1895 and 1925, nearly 100 artists, sculptors, writers, designers, and well-known politicians chose Cornish as the area where they wanted to live either full time or during the summer months. Parties, drama, theater, games, and any kind of art you can imagine went on there. There is even a historical marker!

And even a book! Yes, of course, I ordered it.

Herbert and Adeline began spending summers at Cornish in late 1890. They purchased land in nearby Plainfield and built a house, which he named “Hermitage”. The home, which included an outdoor amphitheater (now, who doesn’t need their own amphitheater?) for theatrical presentations, was designed by his artist friend, Charles A. Platt. President Woodrow Wilson’s first wife, Ellen, a seasonal resident of the Colony, wrote her husband daily in 1913, and said, “Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Adams are among the choice spirits of the Colony both intellectually and spiritually.” Among his other talents, Herbert was also apparently an ace at charades! The Adams spent 40 summers at the Colony. Yet, they called New York home.

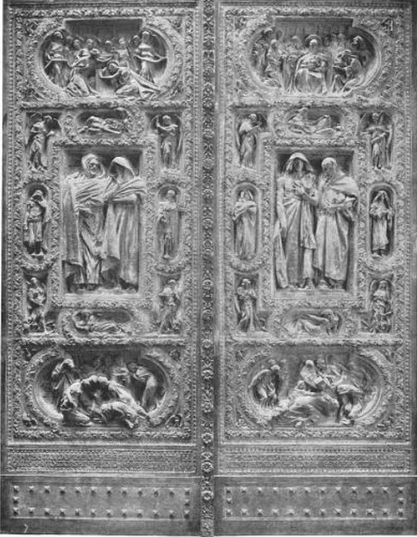

So what was Herbert doing the rest of the year? In 1890 through 1898, he was an instructor in the art school of Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York. He was elected into the National Academy of Design in 1898: and in 1906, was elected vice president of the National Academy of Design, New York. Herbert later served as President from 1917 to 1920. He was also part of the American Numismatic Society (a fancy name for all things relating to coins, paper currency, and medals). Archer M. Huntington was also a member and paid for the museum’s expansion in 1929. Anna Hyatt Huntington also designed medals. As you can see, there were several overlapping ways that Archer and Herbert could have met. Their wives already knew one another. And Archer needed an amazing sculptor. But why Herbert Adams specifically? Let’s have a look at some of the doors he had already designed:

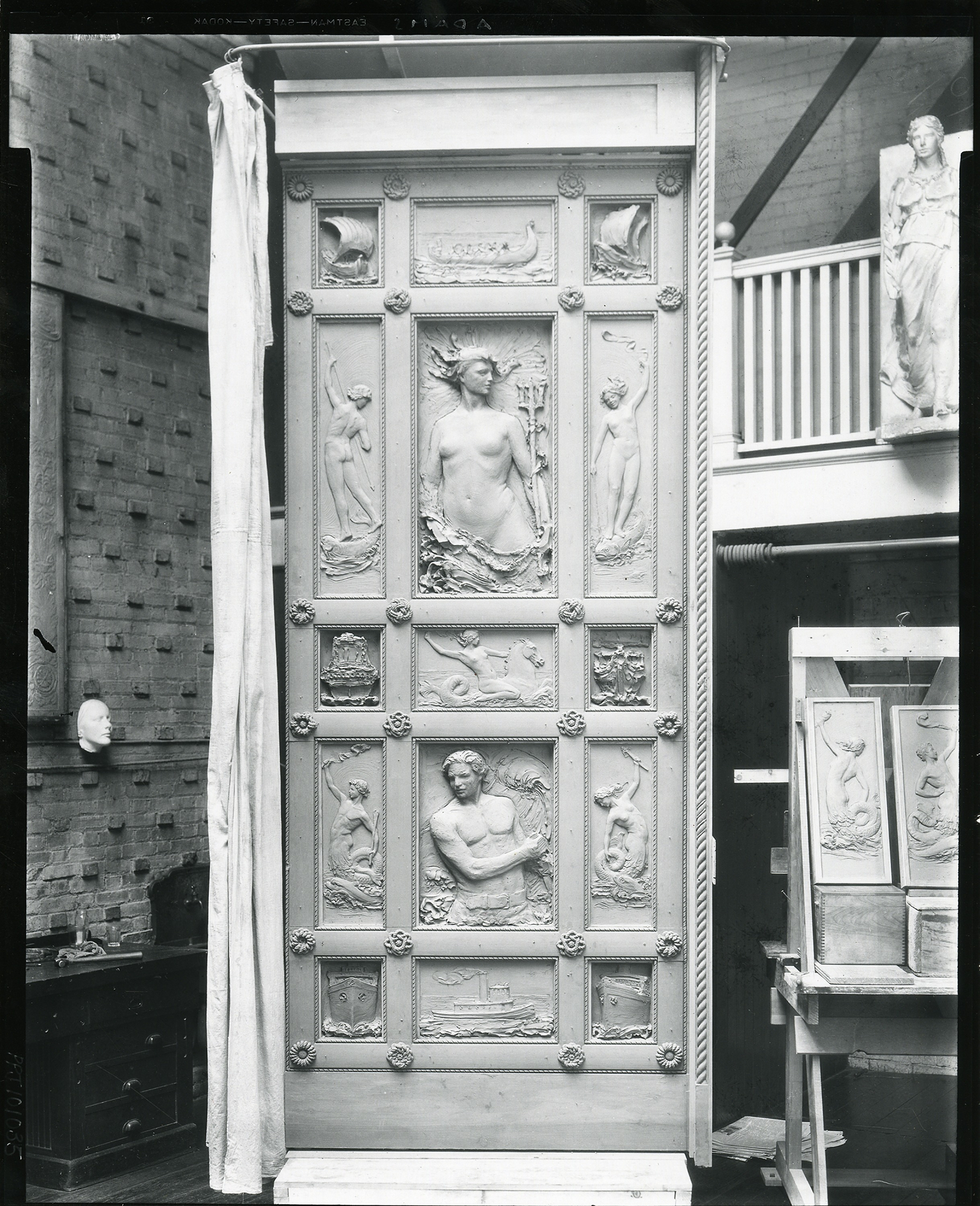

The Bronze Doors at The Mariners’ Museum and Park were commissioned in 1932. Commenting on the commission, Herbert Adams said, “The history of shipping and the mythology of the sea allowed for freedom of fancy and freshness, and a variety of ornament.”

He created the clay sculptures over the next three years, done panel by panel. The bad relief panels include historic ship designs, detailed sea life, images of man working and navigating the sea, maps of continents and heavens, and mythological creatures, all surrounded by historically accurate maritime rope and knot-work.

In August of 1935, the Gorham Company of New York cast the central doors and transom piece in Providence, Rhode Island (my home state!). They were shipped to Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock via a ship of the Merchants and Miners Transportation Company. They were moved to the Museum in November and by January of 1936, the central doors and transom had been installed, cleaned, and patinaed. In November of 1936, the side panels were completed and shipping in March of 1937, and then installed. The doors were completed in June of 1937. The doors include a triptych and are filled with imagery.

Definition of “triptych” 1. a picture (such as an altarpiece) or carving in three panels side by side and 2. something composed or presented in three parts or sections.

Archer M. Huntington wanted his global vision in four massive panels with a transom. His mission was: “This Museum is devoted to the culture of the Seas and its tributaries – its conquest by Man and it’s influence on Civilization” (if you follow our blogs, you’ll know that we’ve updated that a bit). So he did get exactly what he was hoping for, and it’s still a triptych since the center is two doors but it counts as one section!

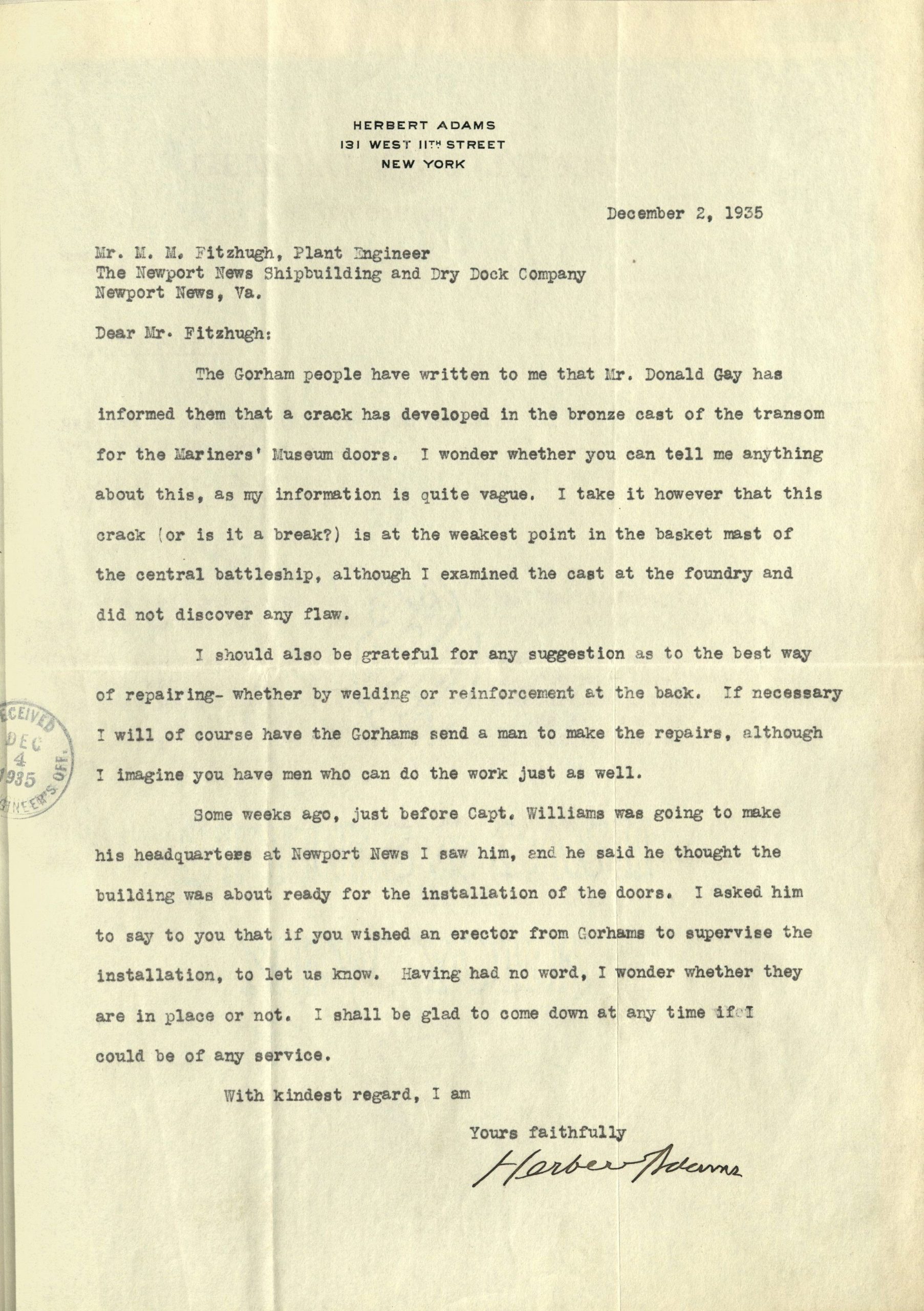

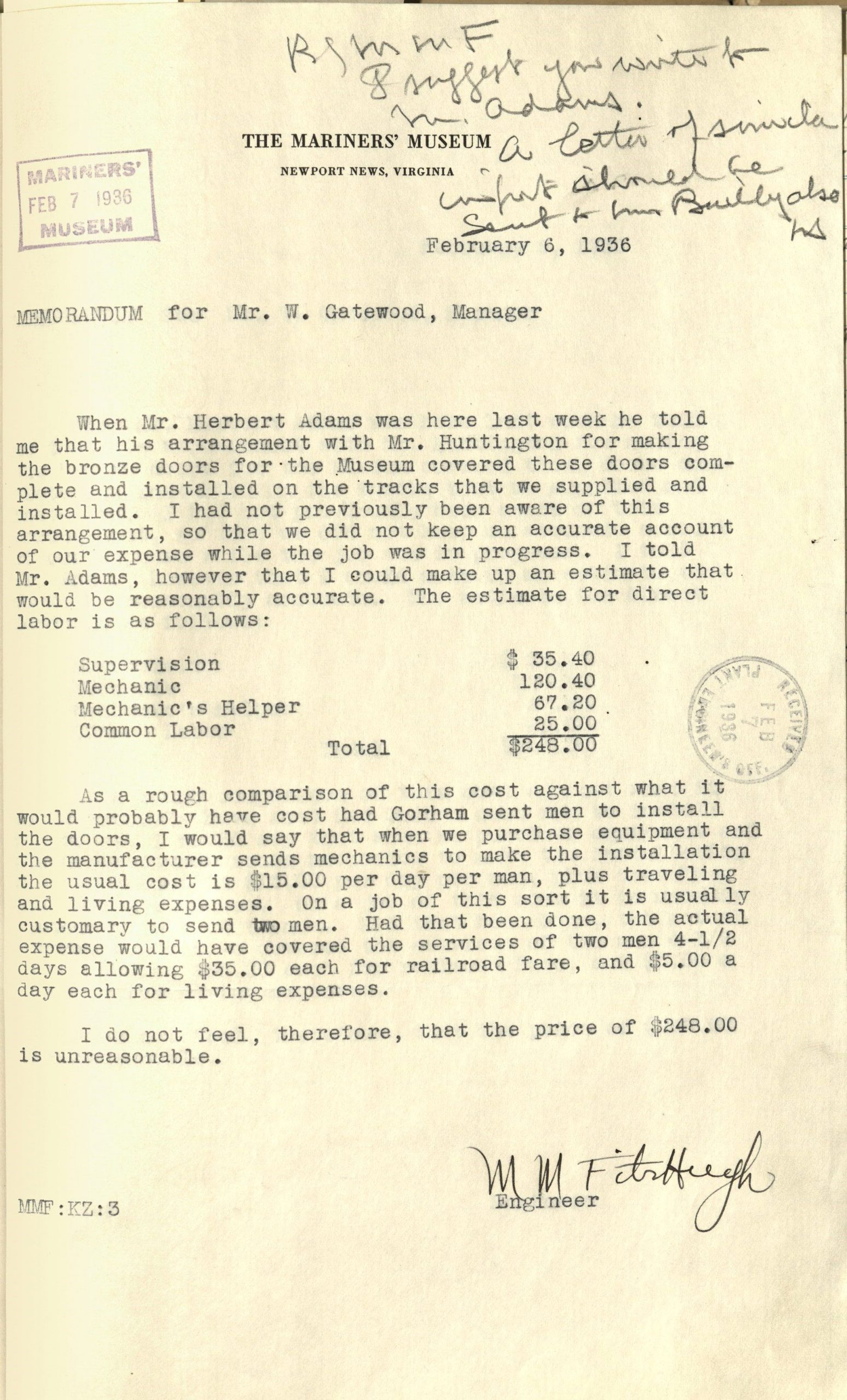

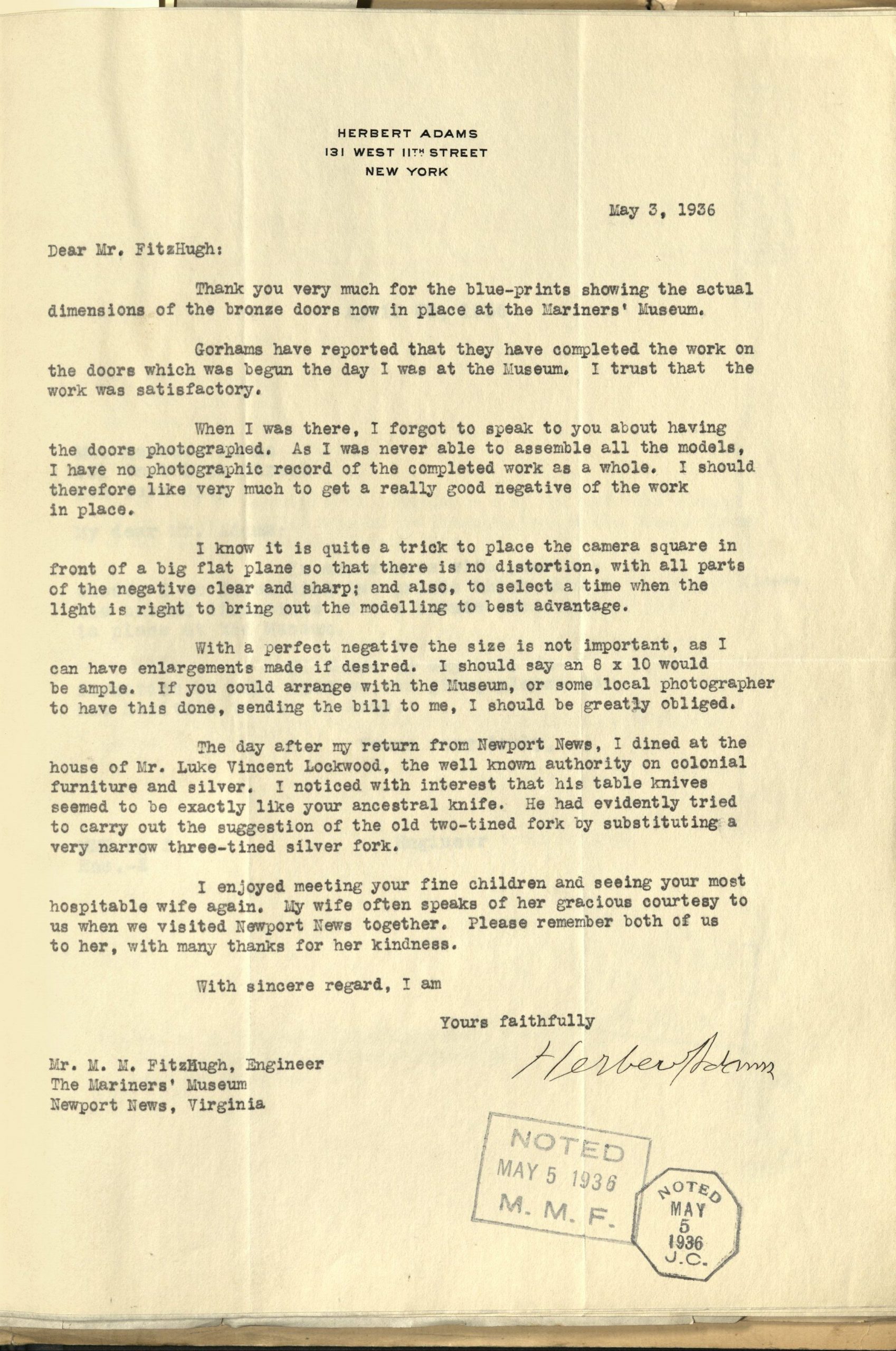

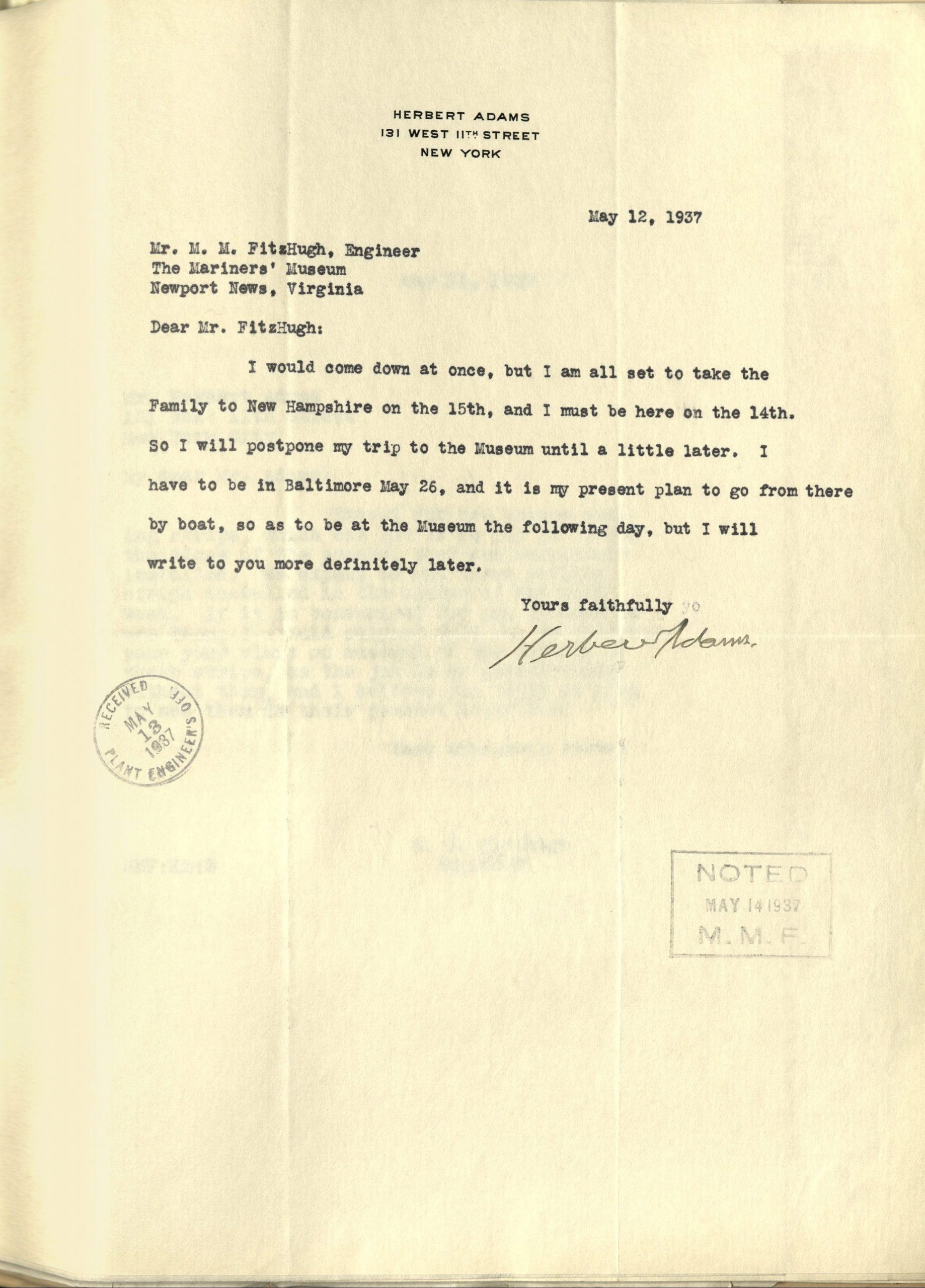

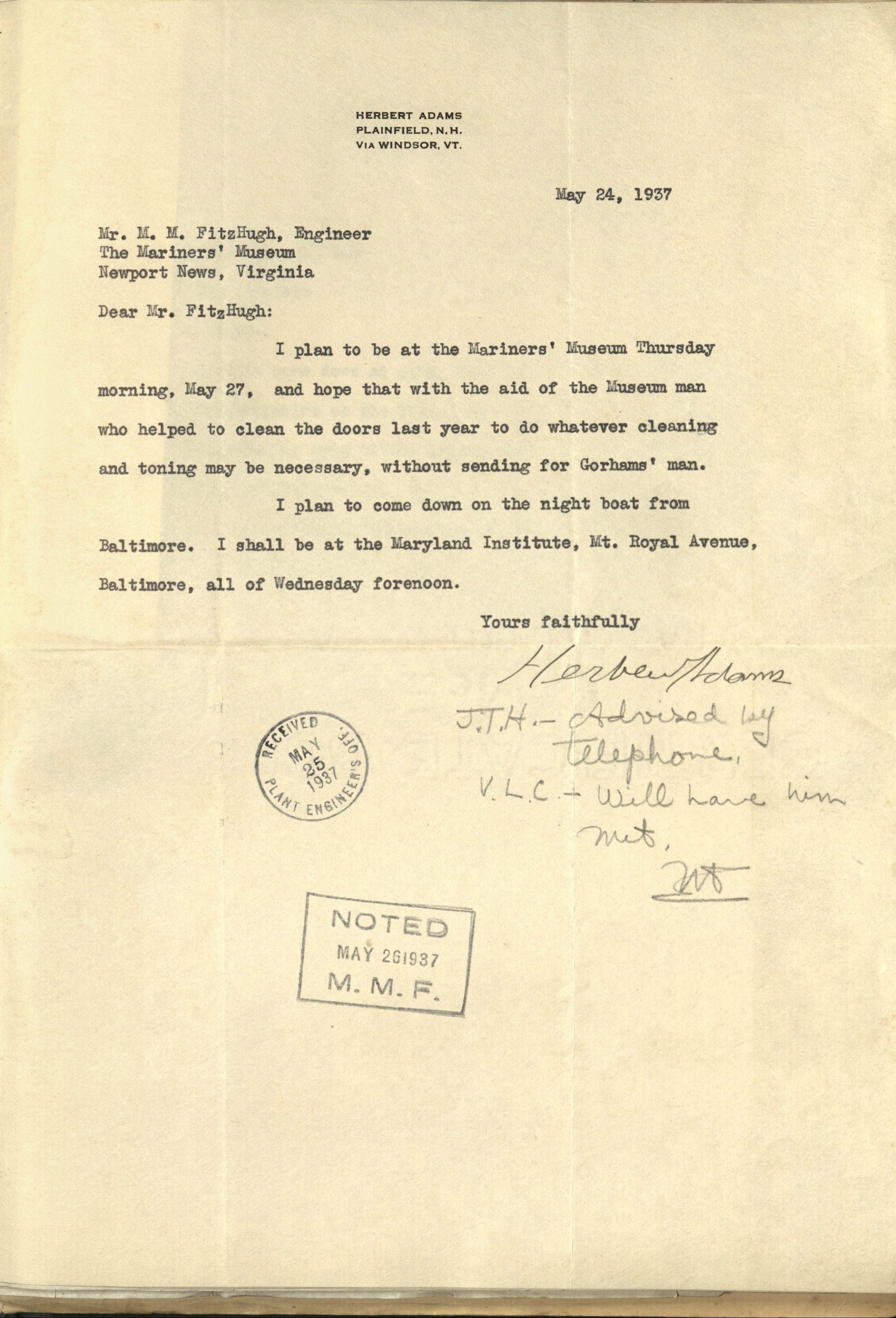

I’m including several letters of correspondence between Herbert Adams and several Museum employees at the time. These are part of our Collection. How awesome is that? You get to read someone else’s mail!

Years ago, well not THAT long ago (10 years?), but in my time at the Museum, we used to close the Bronze Doors every night to cover the inner glass doors. It took quite a bit of effort as the doors are VERY heavy. They slide on a track at both the top and bottom. Well, I was pushing with my back, a rock had fallen in the lower track (unbeknownst to me), the door wouldn’t budge, I shoved harder and threw out my back! It was decided then that maybe the doors should not be moved daily. Our Conservation team does periodic scheduled checks on them and cleaning when necessary. After all, we would like them to last for a very long time!

Aren’t these doors amazing? And even better, you can be part of keeping their legacy alive!

The Bronze Door Society is the oldest, member-managed affinity group of The Mariners’ Museum and Park. This active group supports the Museum’s mission and programs by investing, primarily, in the conservation of our world-class Collection. Each October, members of the Society are invited to cast their vote for a range of projects developed and presented by Museum staff at the Society’s Annual Dinner and Project Selection event. We invite you to join a group of leaders who are playing a role in ensuring the preservation of the world’s rich maritime heritage. To learn more, please visit their website.

Here’s the link to the Bronze Doors in Museum’s Collection catalog. There is a fantastic PDF of a description of the panels in the Bronze Doors, written by Cynthia Katz (awesome long time Bronze Door Society member). I’ve updated a bit of the history in my blog post as we’ve learned more about the artist and the doors themselves.