Many museums begin with a person who has spent their life collecting something they love, which family members may jokingly refer to as “hoarding,” until they come to realize the importance of the treasures. That collection then becomes the basis for a new museum.  The Mariners’ Museum and Park is different in that we started as a museum with a park, and then had to search out and build a collection. This process of purchasing objects allowed us to build a reputation for integrity and authenticity, which then built relationships that led to donations.

The Mariners’ Museum and Park is different in that we started as a museum with a park, and then had to search out and build a collection. This process of purchasing objects allowed us to build a reputation for integrity and authenticity, which then built relationships that led to donations.

After receiving our charter in 1930 the Museum began work on the Park, developing the land and creating what is now The Mariners’ Lake. The focus then switched to the Museum building itself and the collection, and we sent out buyers to search for significant and representative objects to tell the story of all maritime history, not just American.

The field staff began in New England and traveled all over the country, into Canada, and then ventured out on “field trips.” These trips took them to many countries such as Europe and the West Indies including Cuba, Haiti, and Jamaica to name a few. Where they could not go they found reliable, knowledgeable people who could. One man, Captain Irving Johnson, a yacht captain who traveled the world, was hired to explore the Pacific and Asia and all areas along his path.

Before long the objects, books, paintings, and records began arriving in crates at the Museum, where staff began to sort everything. The objects those buyers collected allow us to tell absolutely fascinating stories today, 90 years later, but the stories of the buyers themselves also tend to be pretty incredible!

Some of the funniest stories come from the people who ended up being associated with the Museum for the longest. That only makes sense: the longer you hang around, the more fun we have! Fred and Nola Hill became field representatives for the Museum in 1933, and quickly began traveling around New England. They created lists of objects, which Museum President Homer Ferguson would approve, and they would then purchase. They either loaded down their car with their treasures, or shipped the larger items back. Their work was more important than simply building the collection, they also developed relationships with the people in the many, many communities, building strong connections for the new museum.

One of the funniest things that happened was when the police surrounded their heavily loaded car, asking to see what was in the trunk. As the Hills drove along the road someone had reported seeing a dead body in the trunk of the car and the police were afraid the Hills were murderers! It turns out the “dead body” was our figurehead of the Apostle Paul, whose outstretched hand was so long that Fred Hill was unable to completely close the latch on the trunk! Everyone had a laugh and continued with their day.

Another amusing story with Fred and Nola Hill was their description of what others thought of them. The people in their apartment building watched as they carried all kinds of objects up and down the elevator, and customs agents at the Canadian border wondered why they had collected so many old things. The Hills were eternally grateful that the particular agent didn’t make them unpack their car for inspection, because of the jigsaw puzzle required to piece it all back together. They were not so lucky after a trip to the Gulf Coast, where they picked up numerous shells from the beach. It turned out that the shells’ inhabitants were still there, but not for long in the hot car, which created an odor that I can’t even imagine. The Hills quickly discarded the shells and drove with the windows down for a while.

The story of one agent began over a decade before the Museum. Admiral Bertram M. Chambers was a British naval officer stationed in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1917 to supervise the port during WWI. He casually ate breakfast one morning before leaving the dining room to prepare to head to his office. He reported that not 6 minutes later the entire plate glass window he had been facing exploded in tiny shards from what became known as the Halifax Explosion of December 1917. The French ship, SS Mont Blanc, loaded with explosives, collided with SS Imo creating the largest man-made explosion at the time, followed by a tsunami that killed approximately 2,000 people and wounded over 9,000.

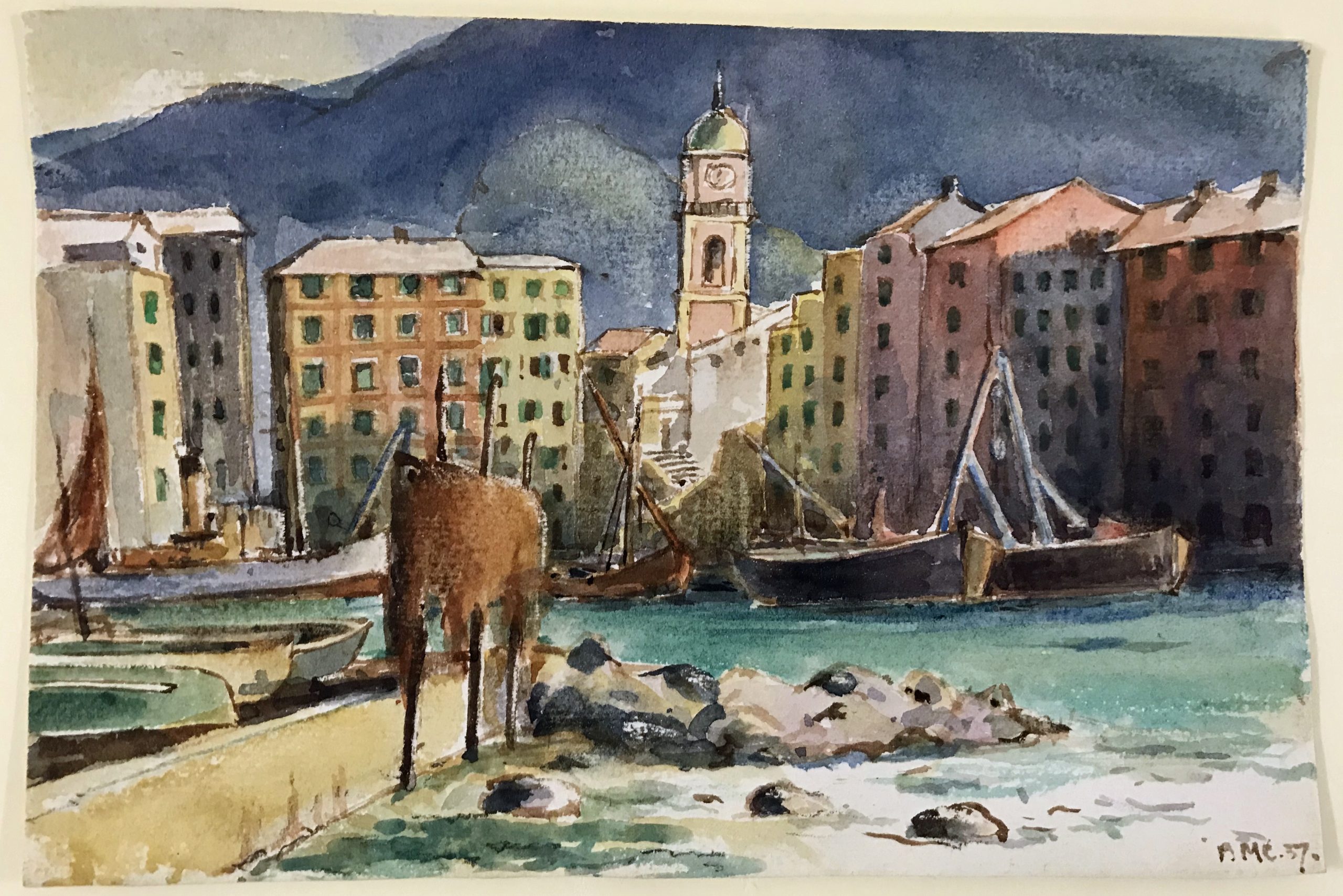

Chambers was lucky! Twenty years later Chambers was retired and working as our agent to purchase objects in England. He traveled to Italy but could find no suitable paintings or other objects at appropriate prices, so he painted his own. We have six in the collection.

The Mariners’ Museum and Park received a steady stream of objects in those days of building the collection, and each one had to be cataloged and sorted. Sadly, one night a watchman saw only a mess of deadeyes on the floor and moved them to a pile out of the way. He didn’t realize that he had undone hours worth of work to sort them all, and the work had to be restarted the next day.

Other field staff, including Isabel Redpath, Earle Smith, and Edward Miles, worked steadily through those early years, but the field trips stopped after 1937, due in large part to the outbreak of WWII. However, the relationships and connections that they developed in those early years have formed a source of strength for our Museum that endures today, 90 years later, with a world class collection representing the entire maritime world.