The Drifter

I’m just an old has-been decoy

No ribbons I have won.

My sides and head are full of shot

From many a blazing gun.

My home has been by the river,

Just drifting with the tide.

No roof have I had for shelter,

No one place where I could abide.

I’ve rocked to winter’s wild fury,

I’ve scorched in the heat of the sun,

I’ve drifted and drifted and drifted,

For tides never cease to run.

I was picked up by some fool collector

Who put me up here on a shelf.

But my place is out on the river,

Where I can drift all by myself.

I want to go back to the shoreline

Where flying clouds hang thick and low,

And get the touch of the rain drops

And the velvety soft touch of the snow.

—Lem Ward (1896-1984)

Master Decoy Carver/Painter, Crisfield, Maryland

WHY DECOYS?

Decoys have their origin with man’s effort to lure waterfowl into range. Whether hunting a net or trap or gunning with a shotgun, decoys became a key hunter’s tool just as important as his boat, blind, and shotgun. When weaponry was improved in the later part of the 19th century and populations increased, more and more people wanted waterfowl to eat or for sport. The situation prompted the need for more decoys. The art of the decoy entailed that the “birds” would appear real from afar. The more a working decoy resembled nature, the more birds the hunter took home.

The waterfowl decoy is now a treasured form of folk art. Often highly sought after as collectibles; many are quite valuable. Nevertheless, whether it is an old working decoy or a modernized, stylized, intricately carved bird, they symbolize technology’s impact on the art, environment, social and economic lifestyles.

WHAT IS A DECOY?

The word decoy is derived from the Dutch “Kooi,” in combination with the article “de” and the noun “ende.” The theory is that the word is a contraction of the Dutch term for cage. The Dutch brought to the New World (New Amsterdam, today’s New York City) an ancient method of using cages, complete with tame ducks to lure wild fowl into a trap. The wild ducks would then be captured, and then the tame birds would be released again in the process of guiding other birds into the cage. These tame ducks would be called the cage ducks or “de kooi ende.”

By the mid-19th century the word decoy became commonplace in America as an image of a bird used to entice within gunshot range. Therefore, decoys are replications of waterfowl. The art of the decoy entailed that the birds be produced to appear as live birds from afar. The more a working decoy resembles nature, the more birds the gunner takes home.

WHEN WERE DECOYS MADE?

While the first decoys can be dated to use by pre-Columbian inhabitants of North America, it was during the post-Civil War era when three factors in American history combined to expand the demand for waterfowl:

Migratory birds such as Canvasback ducks and Whistling Swans had always been in great abundance. But access to and distribution of this seemingly endless food source had been a problem. With a rapidly rising population, America needed to harvest this crop just like oysters or crabs.

The expansion of railroads, connecting the rivers, bays, and marshes with major cities, using refrigerated cars allowed this food source to reach the market craving for the waterfowl’s delicious meat.

Improvements in firearms gave hunters an effective and economical method to harvest birds. The paper shotgun shell enabled more efficient firearms to be produced. First came the lever action and pump shotguns that increased firing speed. Then the automatic shotgun was invented. It became so effective, especially when fitted with an extended magazine, that the apparently inexhaustible supply of waterfowl quickly became endangered, forcing the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

WHY DO THE WATERFOWL COME?

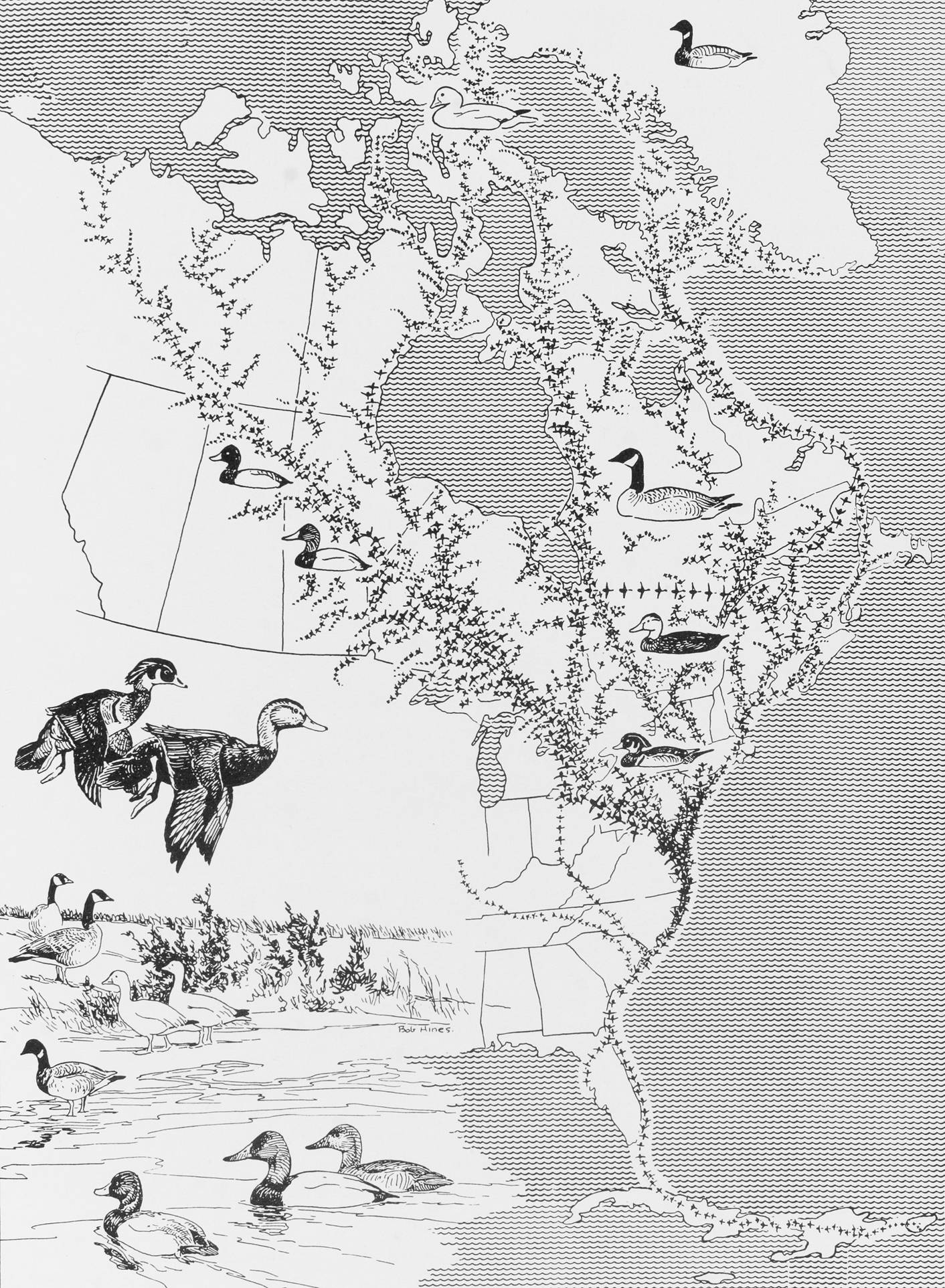

When the crisp winds of fall break across the Chesapeake that is when we hear again the glorious music of the migrant Canada geese drifts throughout the air. Look up into the sky or out above the cut corn fields and you will see their wavering lines off in the distance. You wonder what magic compels these birds to travel thousands of miles each year from their northern breeding grounds to winter spots along the Atlantic coast and back again. How do these birds find their way? When do they know when to go and when to return? These questions are part of the magical mystery of migration.

The movement north and south of migratory waterfowl is probably triggered by meteorological conditions such as barometric pressure and temperatures. The birds travel certain routes to places based on food and water sources. Waterfowl flocks return each year to the same wintering areas because of imprinting.

The Atlantic Flyway welcomes birds from the eastern Arctic, the coast of Greenland, Labrador, Newfoundland, Hudson Bay, the Yukon, and the prairie areas of Canada and the United States. Millions of ducks, swans, and geese move along the coast and winter on the Chesapeake and North Carolina sounds.

The Chesapeake region was a great magnet to migrating waterfowl. These protected waters provided a haven and food. Aquatic grasses filled the waterways, and the harvested fields were sprinkled with corn. The tremendous number of birds flocking to this region prompted the need for decoys.

HOW TO USE DECOYS

The abundance of waterfowl, the development of improved weaponry, and enhanced transportation systems enabled market gunners and sportsmen to harvest thousands of ducks per year. On the Susquehanna Flats at the head of the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland the best hunting method was a sink box. A sink box layout required at least 150 to 300 or more decoys. An estimated 75 sink boxes were in use on the flats during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Another 50 to 100 decoys were also required for a sneak boat and countless shore blind rigs, so thousands upon thousands of decoys were needed every year to support hunting activities. The hunters used certain patterns when putting out the decoys based on species, wind, tide, and type of gunning platform.

HOW DECOYS WERE MADE

The rapid expansion of “market” and “sport” hunting during the post-Civil War era resulted in the need for better gunning tools. This situation prompted many guides to begin making decoys. Decoy making became an important trade which featured regional influences caused by water and weather as well as by paint and body style traditions. The designs developed were then passed from generation to generation. Each decoy maker had his own opinion and thoughts about how each kind of waterfowl should appear.

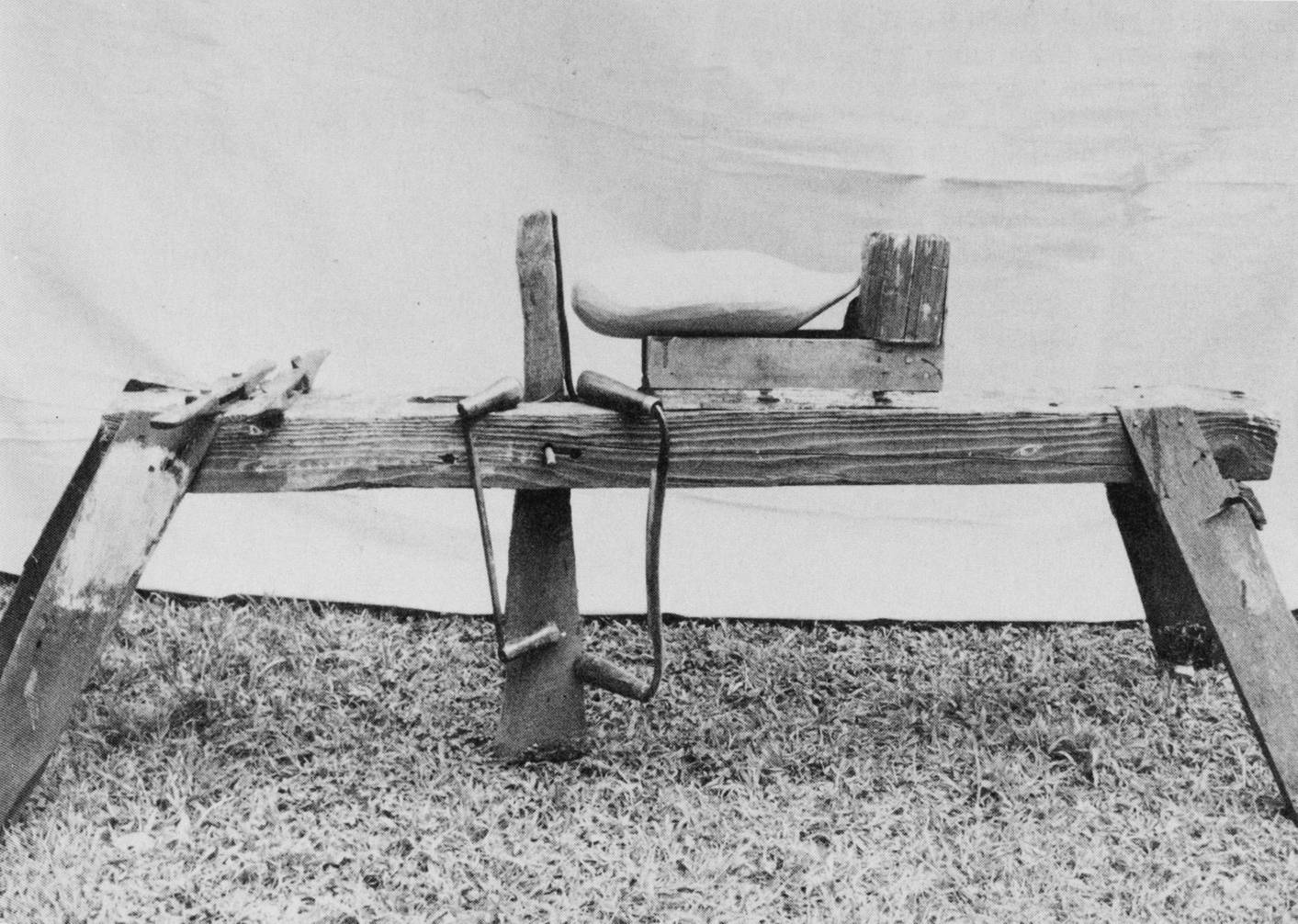

By the mid-19th century the decoy making traditions were established and the “birds” were “hand-chopped” with simple woodworking tools such as axes, chopping blocks, spokeshaves, and various knives. As the popularity of water fowling grew in the 20th century, the need for decoys increased. Industrialization also influenced decoy making just as the decoy market expanded beyond traditional makers’ abilities to fill orders. Consequently, several enterprising businessmen, hunters, and woodworkers endeavored to mass produce and promote decoys.

Other, more traditional carvers, turned to power tools like a duplicating lathe, band saw, and electric sander to increase their output. While some “factories” employed only a few workers and used traditional carving methods, other “duck manufacturers” utilized an assembly line process. What these early factories had in common was that they advertised their product and shipped quality, good-looking birds throughout the nation.

Makers had often attempted making good decoys using material other than wood. Following World War II, mass-produced decoys appeared in cork, canvas, papier mâché, and plastic. Many of these new styles were patented and each promised to bring in the most ducks. As wooden birds increased in price, plastic and other types of decoys became more popular and dominated gunning rigs.

The post-World War I era witnessed the first shift from wooden working decoys to decoys mass produced from other materials. This transition changed the decoy industry. Following World War II, carvers using wood could not compete economically with plastic birds. Carvers then witnessed their work changing from a tool for gunning to a piece of art.

Many people had already recognized the powerful folk art quality of decoys. Traditional decoy makers strove to create more realistic decoys with a raised wing or turned head. Other carvers produced miniatures to provide samples of their work. These “fancy ducks,” as Lem Ward called these early decoratives, began to sell at premium prices. Eventually, some carvers began burning feathers and other specialized techniques using new technologies like dentist tools to make the ultimate — a decoy so lifelike that it could fool even a live duck.

ART OF THE DECOY: FLOATING SCULPTURES

Waterfowl decoys existed for thousands of years before collectors began to appreciate them as a historic art form with the potential for having aesthetic value that exceeded its functional worth.

While many decoys appeared just as simple tools of the bay man’s trade, others assumed an expression of the birds themselves. The material and style do not matter. What happened in the hands of the man who made it does. When a decoy truly captures the bird in body and spirit, then we call it art.

Decoys are one of the oldest and lasting forms of American folk art. Man has taken simple materials such as wood and captured the bird-spirit in a man-made image. These floating sculptures continue to appeal to us today. We admire them as hunting devices, but also because their makers satisfied a natural need for expression and individuality. And so, through a decoy’s making–its carving and painting–a treasured folk art was born.

The art of the decoy is ever-changing. Today’s decoys are a mixture of traditional working decoys and birds created to reflect minutely observed details. Many of these birds are not meant for gunning; yet, many are still used while shooting from a blind. Nevertheless, they continue as a connection to the work of an old bay man who knew birds from living closely with them, and who made his decoys because he needed them.