CSS Virginia Enables the 1862 Defense of Yorktown

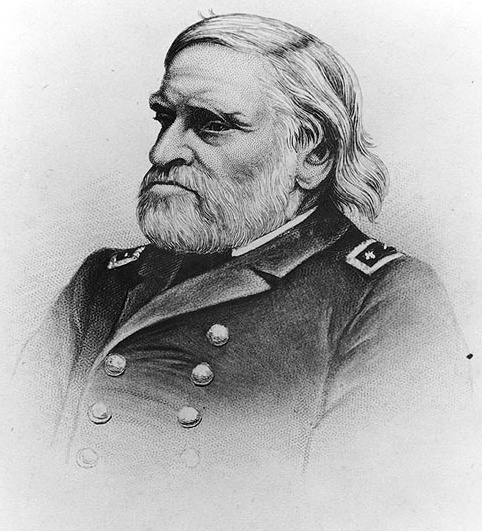

In spring 1862, Union general George Brinton McClellan had assembled a very powerful army around Washington, D.C. The Union had already recently achieved several major victories along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, as well as they had captured the North Carolina Sounds. McClellan’s army was poised and ready to strike at the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. General McClellan, often called ‘Young Napoleon’ or ‘Little Mac,’ wanted nothing to do with a march overland toward Richmond.

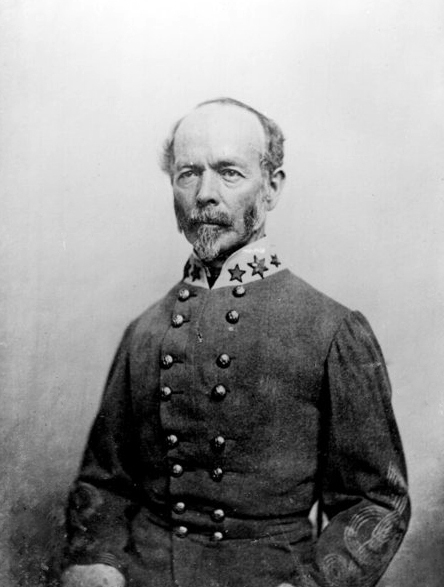

This path was blocked by General Joseph E. ‘Joe’ Johnston’s 45,000-strong army defending Manassas. In an effort to flank and isolate Johnston’s army away from Richmond, McClellan conceived the Urbanna Plan to move his army to the Rappahannock River at Urbanna, Virginia, and then strike directly at Richmond. Before the Union general could implement his campaign, Joe Johnston abandoned his Manassas defenses beginning March 6, 1862, and fell back to Fredericksburg. McClellan quickly offered a secondary amphibious operation to strike at Richmond by way of the Virginia Peninsula.

Pathway to Richmond

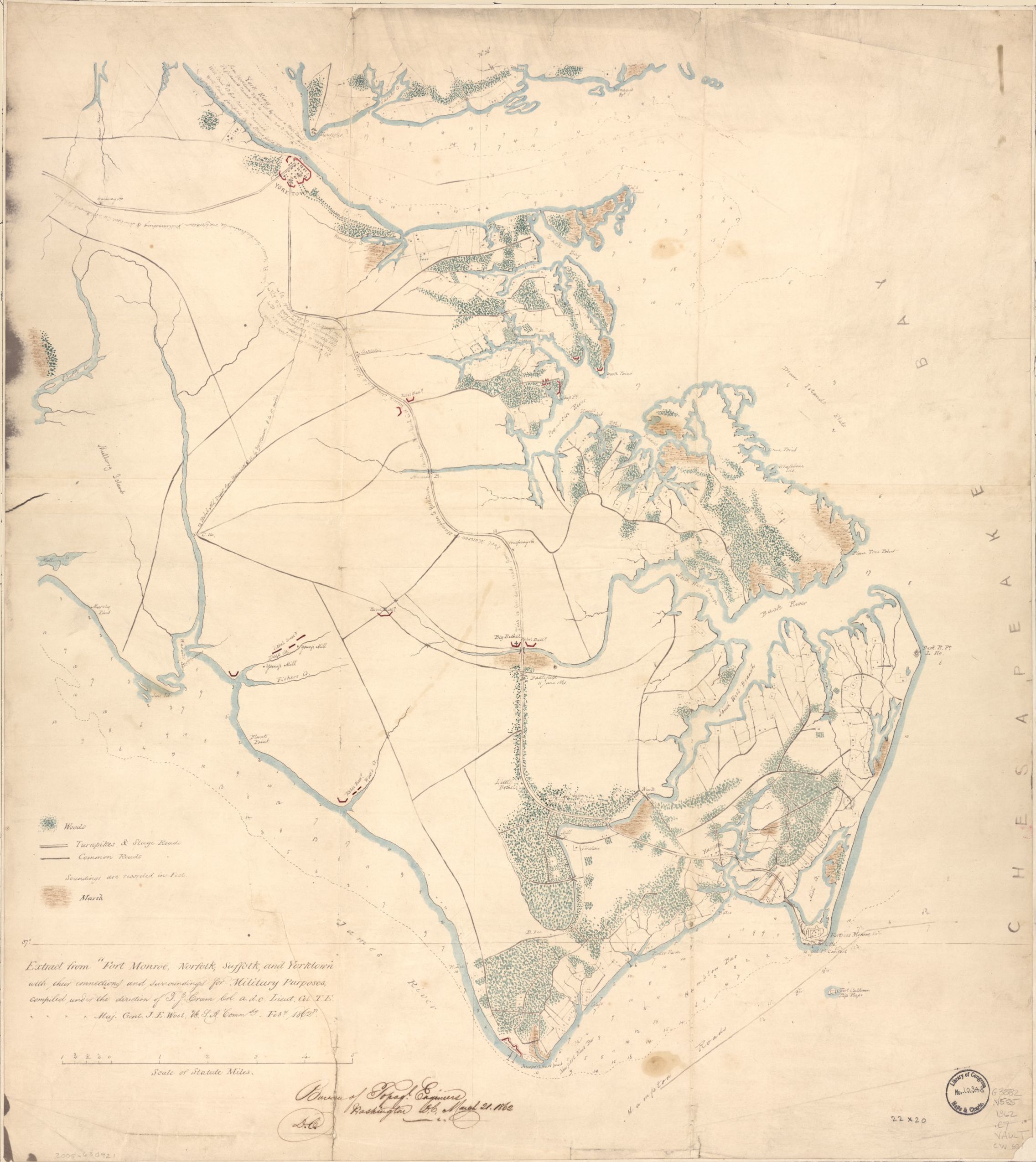

Northern and Southern leaders alike had recognized from the war’s onset the Peninsula’s strategic position.The Virginia Peninsula, bordered by Hampton Roads and the Chesapeake Bay, as well as the James and York rivers, was one the major approaches to the Confederate capital. At the Peninsula’s tip was the largest moat-encircled masonry fort in North America, Fort Monroe. The fort commanded the entrances to Hampton Roads and had been retained by the Union when Virginia seceded.

Even though the Confederates maintained control of Norfolk and the Gosport Navy Yard, Fort Monroe became a major base for Federal fleet and army operations. Accordingly, when Johnston retreated to the Rappahannock, McClellan, on March 8, proposed to President Abraham Lincoln they march against Richmond via Fort Monroe. McClellan’s plan was a sound strategy as it employed a shrewd exploitation of Union naval superiority; gunboats could protect his flanks, and river steamers could carry his supplies and troops towards Richmond.

The Tide of War Changes

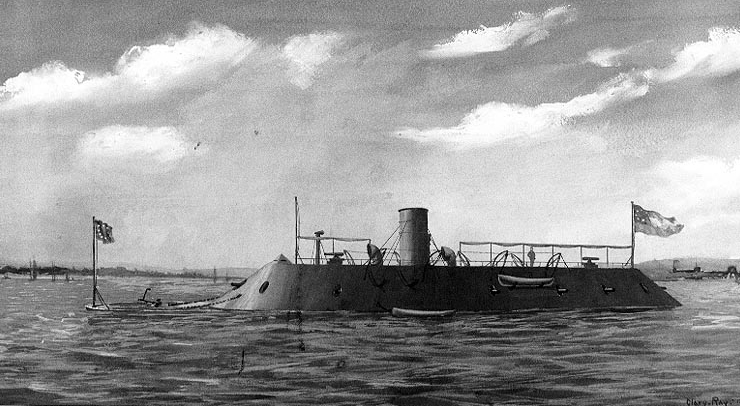

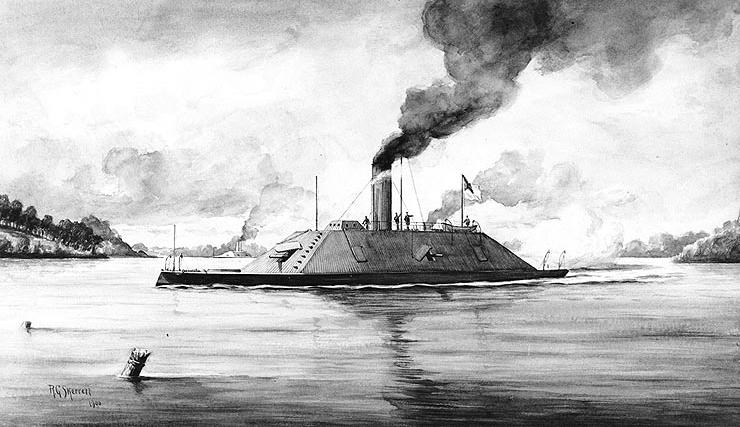

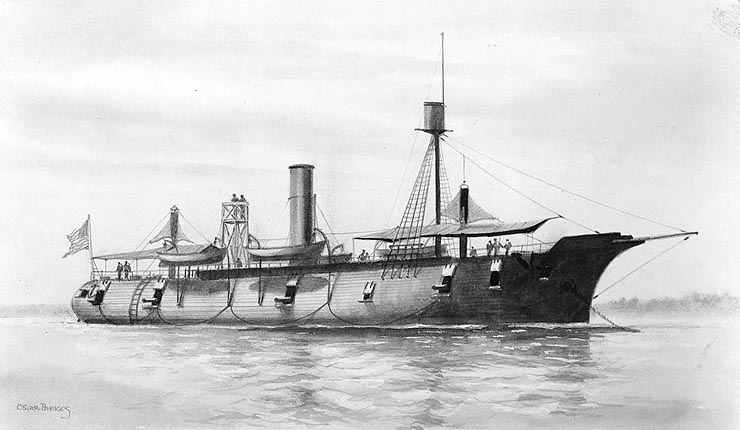

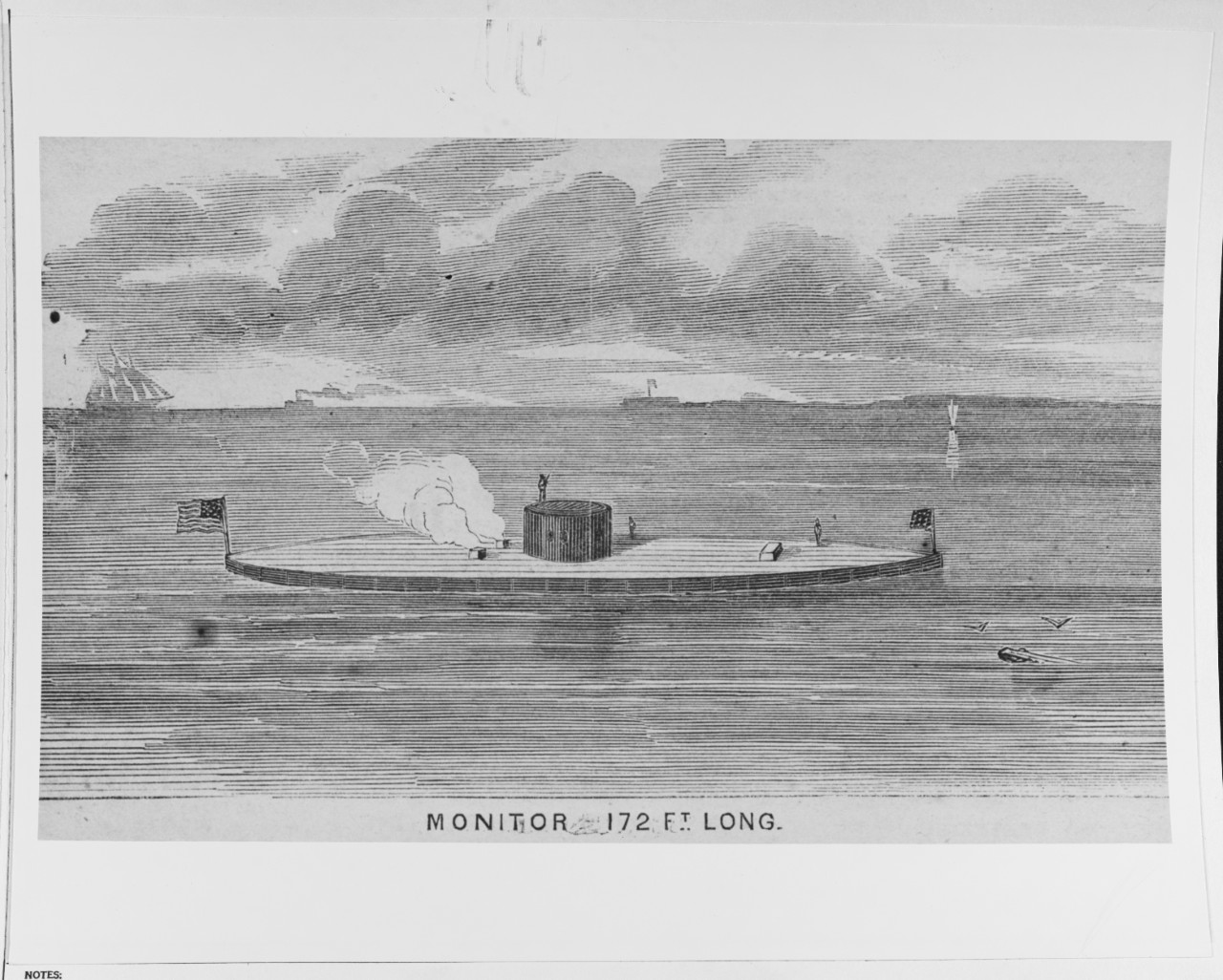

As McClellan shared the merits of his plan with President Lincoln, his campaign started to unhinge. The emergence of the powerful ironclad ram CSS Virginia on March 8, 1862, sent shockwaves through the Union command. Virginia (Merrimack) was converted from USS Merrimack, scuttled when the Federal forces evacuated Gosport Navy Yard on April 20,1862. The ironclad’s construction was a remarkable test of Confederate ingenuity and available resources. In one day, Virginia destroyed two major Union warships — USS Cumberland and USS Congress — as well as two transports; and damaged two Federal frigates, threatening Union control of Hampton Roads.

Lincoln viewed the events of March 8 as the greatest calamity since Bull Run; and Union Secretary of War Edwin Stanton feared that Merrimack (CSS Virginia) would attack the Federal capital. Yet, as the burning Congress illuminated the harbor with an eerie glow, the novel Union ironclad USS Monitor entered the stage. The next day, the Confederate ironclad fought the Federals’ Monitor to a standstill. Monitor had stopped Virginia from destroying the wooden Union fleet in Hampton Roads. While both sides claimed victory, Virginia’s presence, blocking the James River, would continue to delay and alter McClellan’s campaign.

First Stride of the Giant

McClellan remained confident, believing Monitor could hold off any advance against his transports by the Confederate ironclad. Facing Lincoln’s deadline to move against the enemy, he proceeded with his campaign. During March 1862, Fort Monroe and Camp Butler on Newport News Point would receive 389 vessels laden with 121,500 men, 1,224 vehicles, 44 artillery batteries, 102 siege guns, and all the supplies required to support such a huge army. The Army of the Potomac was the largest army to conduct an amphibious operation in North America to date. The grand army was bigger than any city in Virginia at that time.

Confederate prospects looked bleak as McClellan assembled his forces and many Confederates feared that if Richmond were to fall, the Confederacy might collapse. Southern hopes hinged on the ability of CSS Virginia to hold Hampton Roads, and on Major General John Bankhead Magruder’s small Army of the Peninsula to delay the Union juggernaut’s advance toward Richmond.

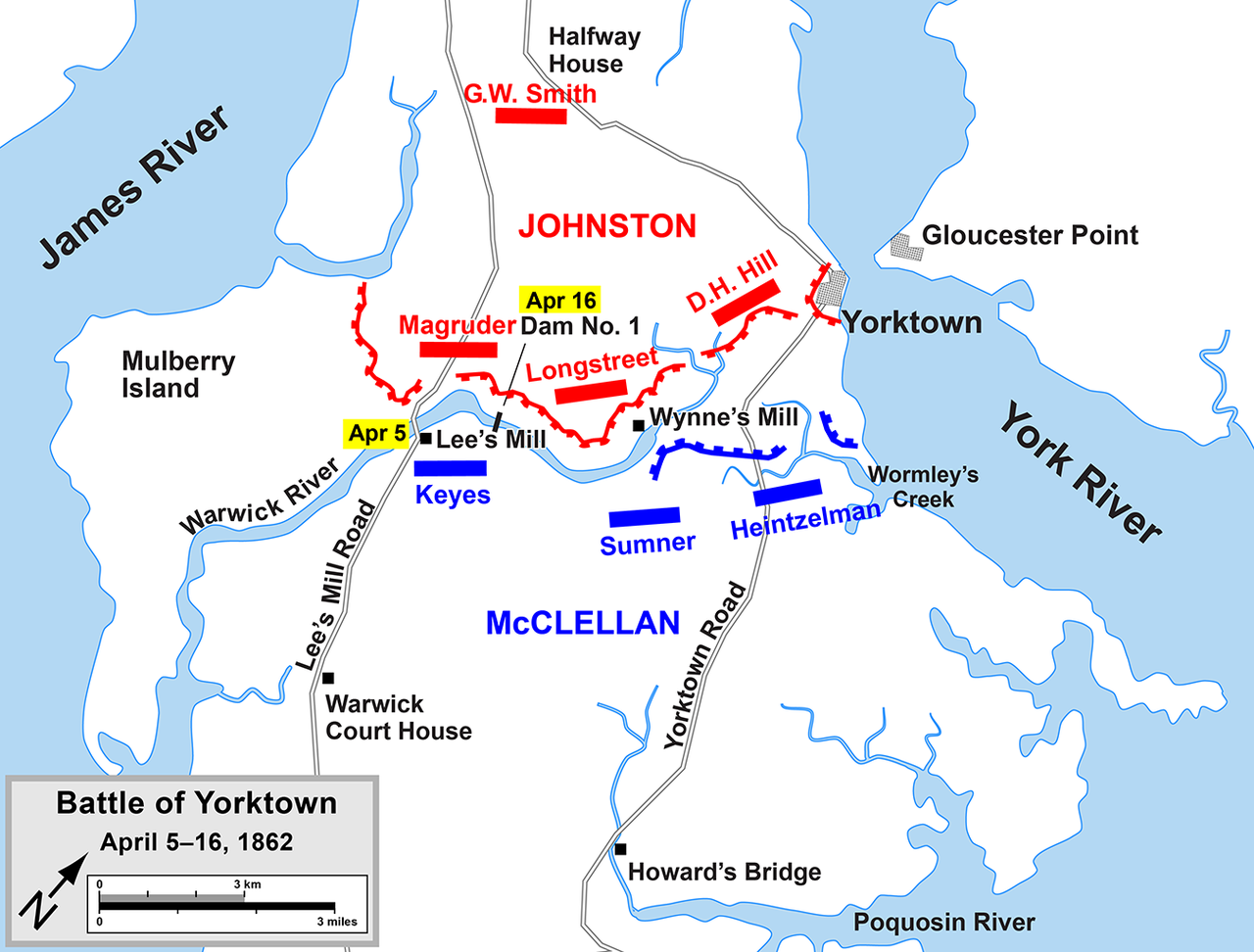

Since Magruder’s June 10, 1861, victory at the Battle of Big Bethel, using his troops and as many as 1,600 slaves drafted from nearby plantations, the commander of the Army of the Peninsula had built three defensive lines to guard against any Union advance from Fort Monroe. The first began at Young’s Mill on Deep Creek and ran to Howard’s Bridge and on to Ship’s Point on the Poquoson River. The second line, the primary defensive position, crossed the Peninsula from Mulberry Island Point, following the Warwick River to near Yorktown. The York River was closed by the Gloucester Point batteries across from Yorktown. The third line was known as the Williamsburg Line, featuring 14 redoubts between College Creek and Queen’s Creek. R.E. Lee advised Magruder that the Warwick River Line was the best place on the Virginia Peninsula to defend this approach to Richmond.

As McClellan began to transfer his army to the Peninsula, Flag Officer Louis Goldborough, commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, advised the commander of the Army of the Potomac that the support he had previously offered was no longer feasible. Goldsborough noted that his primary duty was to neutralize the ironclad Merrimack (CSS Virginia). The flag officer insisted he could only provide a few wooden gunboats to support McClellan’s move against the Confederate York River defenses. Three gunboats were commanded by Commander John S. Missroon. Missroon viewed the Confederate water batteries at Yorktown and Gloucester Point at the narrows of the York River as being too powerful for him to pass with his limited resources.

The Army of the Potomac’s chief engineer, Brigadier General John G. Barnard, noted that Merrimack “paralyzes the movement of this army by whatever route is adopted.” Barnard lobbied McClellan to attack and capture Norfolk first. Such an action would eliminate the Confederate ironclad and open the James River, thus avoiding the need to besiege Yorktown. McClellan decided to avoid this advice, believing that the capture of Yorktown would also result in Merrimack’s capture. This decision would prove to be a major error and was one of the critical causes of McClellan’s defeat.

Flag Officer Goldsborough sought other alternatives to strike against Norfolk since the US Navy did not have the resources to do so and since McClellan was intent on moving against Yorktown. He entreated Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to use his influence to prompt Union general Ambrose E. Burnside to move from Elizabeth City, North Carolina, with a line of march along the Dismal Swamp Canal. Norfolk did not have any defenses to guard this approach. Eventually, Burnside’s command attempted this maneuver against Norfolk; however, the Federal advance was blocked during the April 19, 1862 Battle of South Mills near Camden C.H., North Carolina.

‘Like Fireflies’

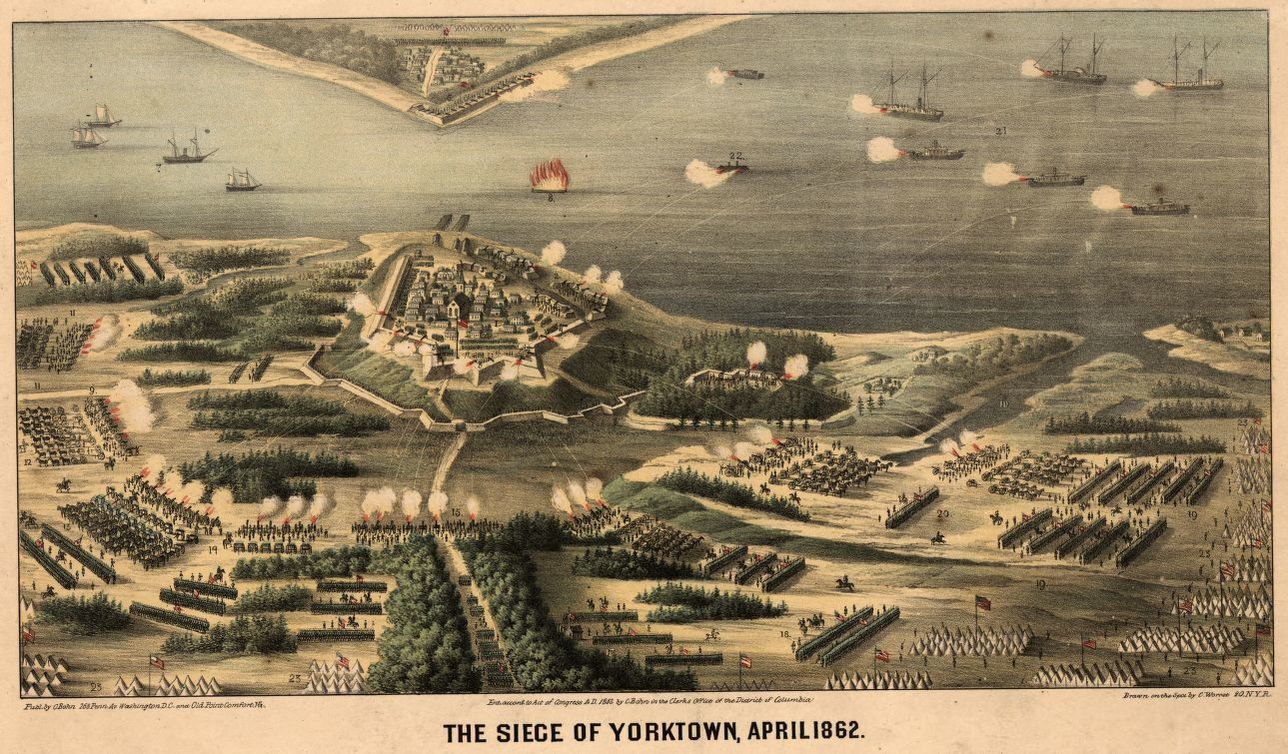

The Union army began its march on April 4, 1862. The Federals reached the first Confederate Peninsula Line at Young’s Mill and Howard’s Bridge to make their stand on the Warwick River. The line was extensive; however, the Confederates had abandoned these fortifications. The next day, the Federal troops marched up the two main roads leading toward Williamsburg, Virginia: the Hampton Road and the Hampton York Highway. On April 6, rain poured in torrents, making the roads virtually impassable. Then the Federals encountered fierce Confederate resistance along an extensive defensive line following the Warwick River, reaching almost to Yorktown. Brigadier General E.D. Keyes noted: the “line is certainly one of the most extensive known to modern times…no part can be taken without a great effusion of blood.”

McClellan stalled in front of the Warwick-Yorktown Line, enabling Maj. Gen. John Bankhead Magruder to stage a carefully organized ruse. Magruder, known as ‘Prince John’ for his elaborate dress and mannerisms, used his 13,000-man Army of the Peninsula to bluff McClellan into believing he had a much larger force. The ‘Master of Ruses and Strategy’ paraded his troops back and forth along his fortifications. “It was a wonderful thing,” wrote diarist Mary Chesnut, “how he played his ten thousand before McClellan like fireflies and utterly deluded him….”

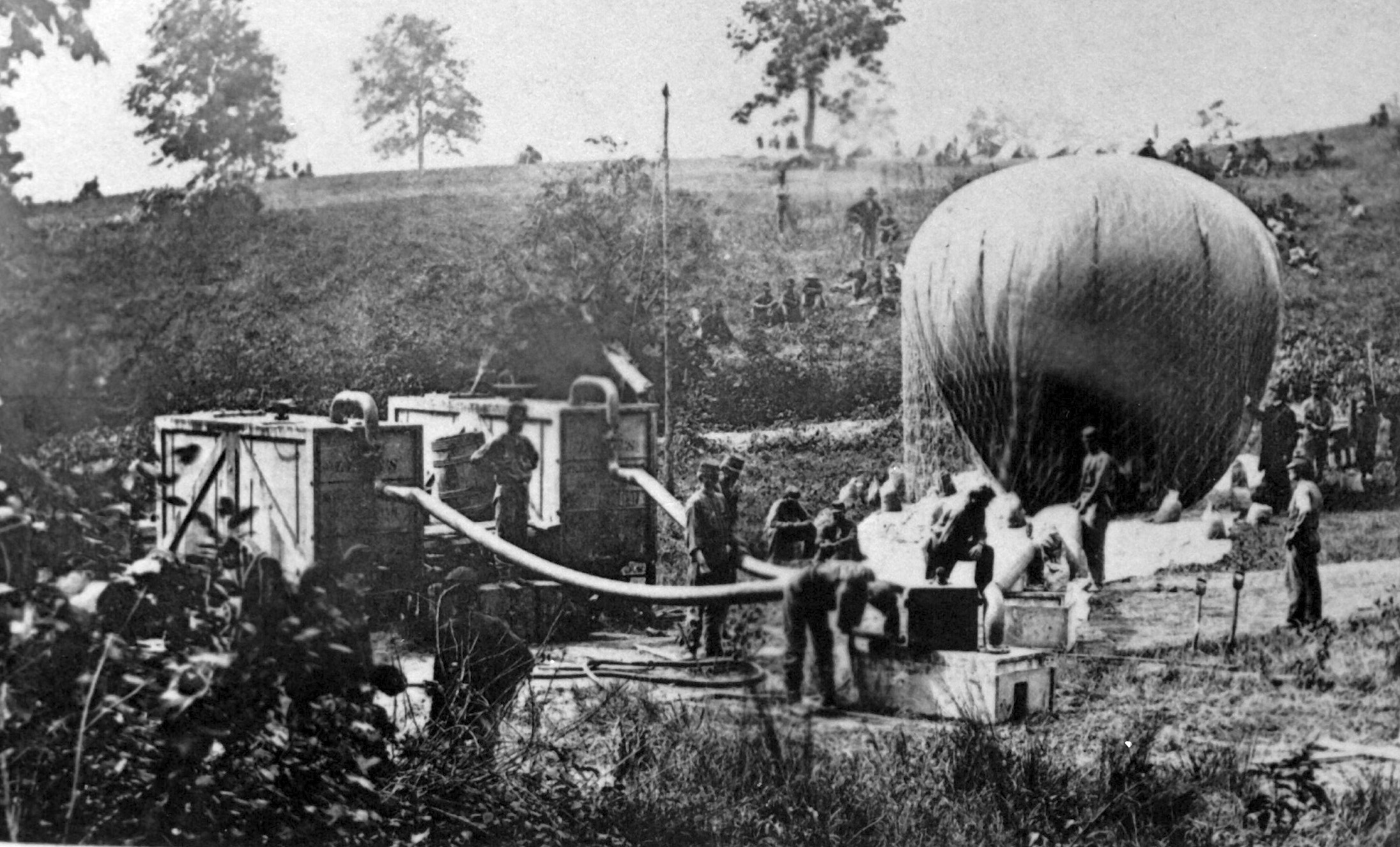

View of balloon ascension, ca. 1862. Mathew Brady, photographer. Courtesy Library of Congress.

View of balloon ascension, ca. 1862. Mathew Brady, photographer. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Even with information provided by Thaddeus Lowe’s balloons and Allen Pinkerton’s detectives, McClellan was convinced he was outnumbered. Since Goldsborough refused to provide more naval support to run past the Confederate heavy batteries defending the York River, the Union general felt he had no other option than to conduct a formal siege of Magruder’s defenses.

Ram Fever

Flag Officer Louis Goldsborough was suffering a dreaded disease in Spring 1862 called ‘ram fever’ or ‘Merrimack on the brain.’ Gideon Welles advised ldsborough that Monitor was the superior ship. He said the Union ironclad “might easily be put out of action in her next engagement and that it would be unwise to place too great dependence on her.” Goldsborough wished to have yet another ironclad on hand, like the soon to be commissioned USS Galena, to deal with the Confederate ironclad monster.

The flag officer feared that Merrimack (CSS Virginia) could strike the Union fleet again and be held near Fort Wool, under the protection of Fort Monroe’s heavy guns. Unbeknownst to Goldsborough, Virginia had gone into dry dock for repairs and improvements, including the addition of a 12-foot-long cast iron ram with a steel tip, designed to reach under Monitor’s armored deck to pierce its vulnerable hull. While the flag officer did not recognize the opportunity to attack the Confederate ironclad while under repair, he had also learned that the Confederates were building yet another ironclad at Gosport Navy Yard. Later known as CSS Richmond, Goldsborough viewed a second Confederate ironclad as a major threat to Union operations on the York River.

Stalemate Continues

CSS Virginia finally left Gosport’s Dry Dock #1 on April 4, 1862, and on April 11, came out from the Elizabeth River into Hampton Roads to challenge Monitor to a duel. Monitor remained near the harbor’s entrance, hoping to lure Merrimack to the deeper water in the Chesapeake Bay so that rams like USS Vanderbilt could help capture the Confederate ironclad. In turn, Virginia hoped to fight Monitor in Hampton Roads. The Confederates had concocted their own plan to capture Monitor by boarding.

Based on information gleaned from a February 1862 article in The Scientific American, the Southerners thought by using hand grenades, chloroform, and tarpaulins to cover Monitor’s blowers, smokestacks, and pilothouse, they could board the vessel, capturing the ironclad ‘live.’ Despite all of these plans, that drama was not to unfold. Virginia merely steamed back and forth within the roadstead as CSS Jamestown captured three transports. Then, Virginia’s new commander, Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall, ordered his ironclad back to Gosport. Flying the captured transports’s flags upside-down under the ironclad’s own colors, Virginia fired a few shells to windward as an act of disdain.

‘Equal to Five Thousand Men’

A correspondent of the New York Herald wrote on April 12: “The public are justly indignant at the conduct of our navy in Hampton Roads.” Acting Assistant Paymaster William Keeler of USS Monitor expressed his frustration in a letter to his wife that no battle was joined between the two ironclads: “I believe the Department is going to build a big glass case to put us in for fear of harm coming to us.”

The Confederates were overjoyed by their apparent success. Major William Norris, CS Signal Corps, noted that Virginia was the right wing of Magruder’s army, “equal to five thousand men.” General Robert E. Lee, then military advisor to President Jefferson Davis, wanted Virginia to attack the Union transports and scatter McClellan’s army to the wind. Until the Confederates had finished building CSS Richmond in Gosport Navy Yard, it was not prudent to risk Virginia on such a mission.

Virginia’s value in April 1862 was in the protection of Norfolk and the closure of the James River to the Union’s use. These factors lengthened McClellan’s siege of Yorktown which had long- ranging implications on the success of the Peninsula Campaign. Despite the ineptitude of Union naval leadership during this campaign, McClellan would be able to besiege the Confederate defenses at Yorktown.

References

Available in the Museum’s Web Shop:

CSS Virginia: Sink Before Surrender, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://shop.marinersmuseum.org/sink-before-surrender-pb.html&sa=D&source=hangouts&ust=1587055613966000&usg=AFQjCNGlDlDHoLEWTXRLO71bPBmtARqV5A

The Monitor Boys, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011.

The Civil War on the Virginia Peninsula, John V. Quarstein. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1997.