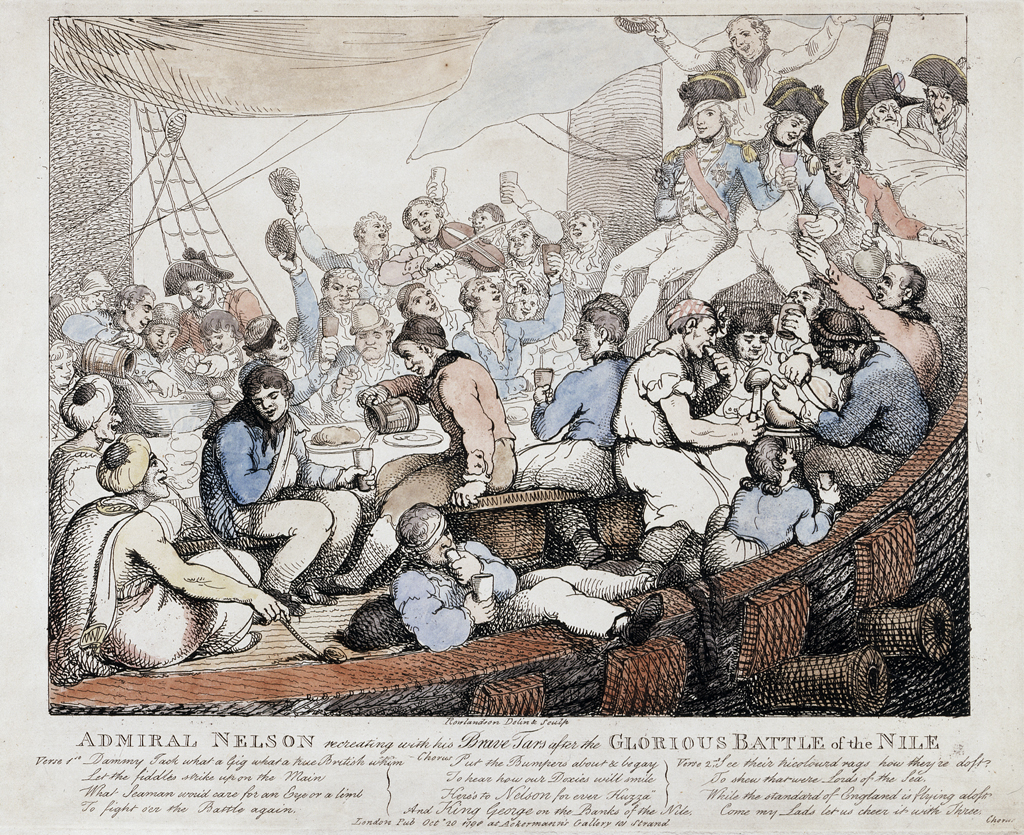

When planning this year’s Gallery Crawl I decided to include a station focusing on a well-known seafaring tradition: the line crossing ceremony. If you’re asking yourself “what the hell is a line crossing ceremony?” and are planning to attend the Crawl let me just say you are in for a real treat! While surveying the collection for items to display I was surprised to discover that I had to look at some of the oldest books in the library; which, of course, made me supremely curious about the ceremony’s origins and how it developed into the crazy ritual it is today.

The tradition developed sometime after 1418 which is when expeditions coordinated by Prince Henry the Navigator began tentatively working their way down the Atlantic coast of Africa. By 1473, Portuguese explorer Lopo Gonçalves had reached and crossed the equator. Interestingly, no one on these early voyages mentions celebrating passing the equator, or anything else for that matter other than arriving back home alive! Presumably, these sorts of events wouldn’t develop until voyages became so frequent they were considered “normal.”

Sea voyages in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries were long, grueling, dangerous affairs so it’s easy to imagine taking a few minutes to thank your lucky stars whenever the crew successfully navigated the ship past some threshold or landmark, especially if it was known to be navigationally hazardous. For sailors who survived these voyages and were passing these same places again, the idea that those on board who hadn’t ever passed these locations should mark the occasion in some way developed into an initiation ceremony of sorts. The ritual most frequently associated with these initiations was baptism with seawater.

In Europe, there is a long history of baptisms occurring at places like Cape Kullen (on the Kattegat on the west coast of Sweden), Pointe du Raz (which sticks out into the Atlantic from Brittany in France), and the Strait of Gibraltar just to name a few. While it didn’t mean quite the same thing to passengers, for sailors these initiation ceremonies heralded the transformation of a “novice” (only because he hadn’t passed that location before) into a fully qualified sailor. The physical and mental trials the sailor underwent during the ceremony were simply meant to prove his courage, endurance and ability to put up with physical and mental pain; traits commonly needed during extended sea voyages.

As sailors traveled further and further from their home ports these same traditions were extended to new landmarks and locations. Sometimes, the locations weren’t physical but conceptual—like the Tropic of Cancer or the equator. There are a few reasons why the equator may have developed into a point of celebration and baptism. First, it was the point where a change in navigational technique was required because Polaris (the Pole Star) dipped below the horizon and could no longer be used to help determine latitude. Also, crossing the equator could be quite difficult thanks to the windless zones that guarded each side (called the Doldrums). The intense heat of the Doldrums damaged the ship; turned food and drink bad; drove men unaccustomed to such heat crazy; and caused epidemics of disease, scurvy and fever that resulted in high death rates among the crew. If a ship managed to navigate through this region without being stranded for days, weeks or even months unable to go forward or back why not take a moment to give thanks for a fast or successful crossing? Finally, early sea voyages tended to be long, arduous trips that might last for several years. Why not give the crew a chance to let loose and have some fun as a way of boosting morale?

The first account documenting a commemoration at the equator was made by French explorer and navigator Jean Parmentier while voyaging to Sumatra in 1529. Parmentier states that on the morning of May 11th fifty people were “knighted” as the ship passed the equator. They then sang the mass of Salve Sancta Parens [the mass of the Blessed Virgin Mary as our savior] “for the solemnity of the day” and enjoyed a “feast of chivalry” with boiled yellow-fin tuna and bonito.

Obviously everyone on board felt something important had taken place that needed to be recognized and while Parmentier doesn’t mention baptism, knighting people simply because they had crossed the equator doesn’t seem like a normal everyday event (although the French do tend to call sailors “chevalier de la mer” [knights of the sea]!). Although his description indicates the ceremony was fairly solemn, it does give the impression that by 1529 commemorating the crossing of the equator in some way was a regular occurrence.

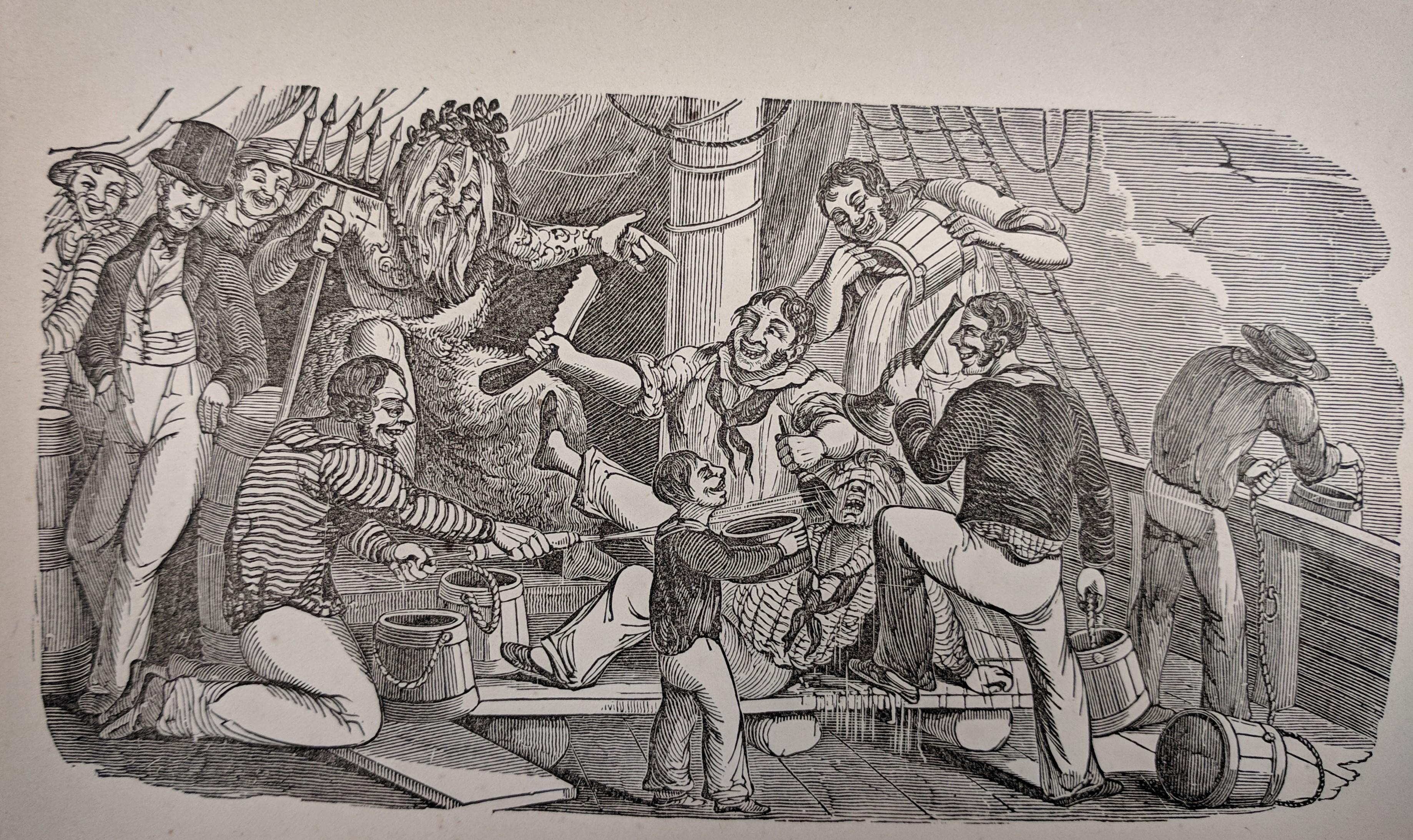

Just twenty-eight years later (1557), a description by French Calvinist missionary Jean de Léry shows the ceremony has evolved into something a little more irreverent as “ceux qui n’ōt jamais passé l’équateur” [those who had never crossed the equator] had their faces blackened with soot from the bottom of a cooking pot and were bound with ropes and ducked in the sea. And there it is! Our first clear indication of ritualized baptism at the equator. He also makes sure we understand that this was a customary practice for the sailors (“les matelots sirēt les ceremonies par eux accoustumees”).

The evolution of the rite continues with Jan Huyghen van Linschoten who describes a ceremony that occurred during his 1583 voyage to the East Indies. Linschoten is the first to mention a “master of ceremonies” and that, at least for a short period of time, the ship was essentially turned over to the crew. He states “the ships of an ancient custome, doe use to chuse an Emperour among themselves, and to change all the officers in the ship.” Linschoten also gives us a hint that serious amounts of alcohol were involved in the event. In this instance it caused their celebratory feast to degrade into a drunken brawl: “…there fell great strife and contention among us, which proceeded so farre, that the tables were throwne downe and lay on the ground, and at least a hundred rapiers drawne, without respecting the Captain [who was apparently laying on the deck drunk!], or any other, for he lay under foote, and they trod upon him.”

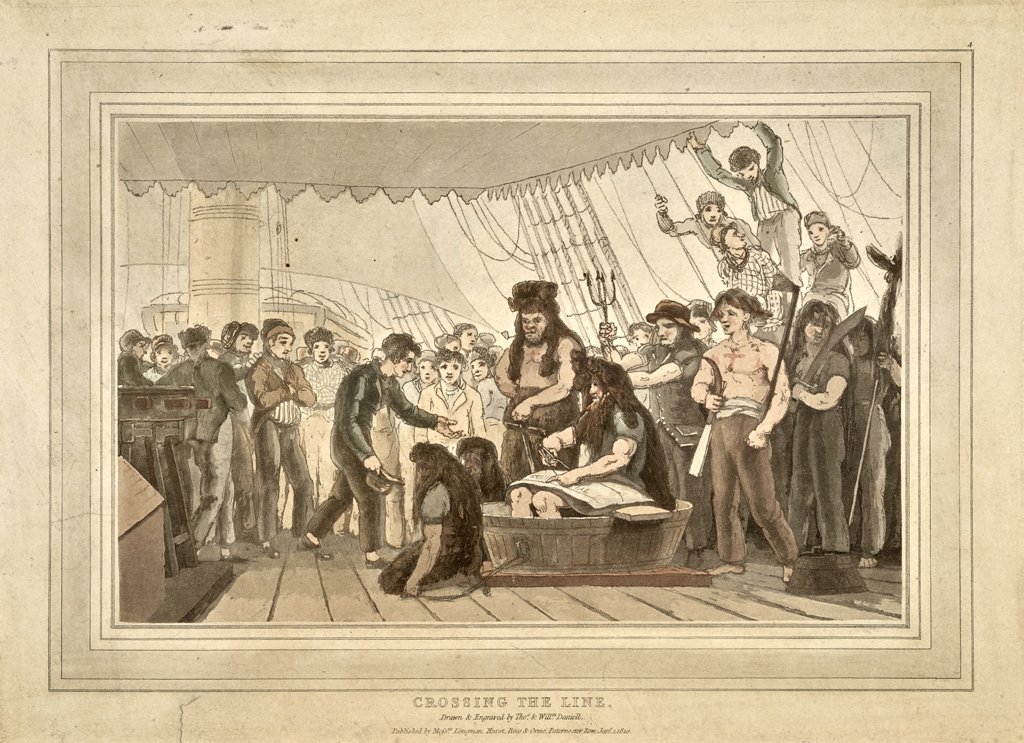

Moving on, Friar Claude d’Abbeville’s 1612 account shows that baptisms are beginning to be held on the deck in lieu of the more hazardous ducking from the yardarm. While most accounts after this point show that deck baptisms were the norm, ducking from the yardarm still occurred on some English and Portuguese ships until the mid-eighteenth century.

By Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre’s 1654 Histoire generale, des isles de S. Christophe, de la Guadeloupe, de la Martinique, et autres dans l’Amerique the “ancient custom” of the line crossing ceremony has become “ridicule & plaisante” [ridiculous and amusing].” The event he describes is really starting to resemble the ceremony that occurs on modern US Navy ships: elaborate preparation, fantastic costumes, blackened or painted faces, grand processions, initiates brought before a judge and sentenced to duckings or baptism with seawater, and the whole event ending with excessive rejoicing and debauchery!

But what about Neptune? The idea that Neptune has some sort of relationship to the event first appears in Guillaume Coppier’s circa 1640 account Histoire et Voyages des Indes Occidentales; although in this instance it was more of a way of paying homage to him during the ceremony as a way of ensuring calm waters and favorable winds on the rest of the voyage. Neptune’s first physical appearance occurs in Jean François Michel’s 1752 Journal du voyage à la Chine. Interestingly, in this account from the Prussian ship Burg von Emden, Neptune only appears as a witness to ceremonies conducted by the ship’s captain.

Just a few years later, Antoine-Joseph Pernety’s 1763 Histoire d’un Voyage aux Isles Malouines shows the character of Neptune (in this instance as his french self—Bonhomme la Ligne) and the ceremonies surrounding him are fully developed. Pernety states the crew spent a week planning the festivities and a “courier” arrived the day before to announce the impending arrival of Bonhomme la Ligne. The next afternoon the crew placed a tub of seawater on the deck and stretched a rope across the ship to represent the “line.”

Penety describes Bonhomme la Ligne as “covered with white sheep skins sewed together so as to make a garment of one piece. His cap, which was composed of the same materials came down over is eyes. A quantity of tow mixed with wool served him for a peruke and a beard. He had a false nose made of painted wood. Instead of a ribband, he wore across his shoulders a string of trucks of the parrels [strings of wooden beads that help the sails ride up and down the mast], as large as goose eggs.” Bonhomme’s “attendants” were dressed in a similar manner, although some had their bare limbs painted red or yellow and they carried clubs, maces, bows and a large Indian peace pipe. His attendants included guards, a chancellor bearing his sceptre (a cannon swab), the cockswain dressed as Bonhomme’s daughter, and a vicar with four attendants (cabin boys) carrying the accoutrements of his office.

Apparently nearly everyone on board (a few mothers with scared kids being the exception) went through the ceremony in some way or another but the manner of their “baptism” was different depending upon whether they were male or female, had offered some sort of tribute to ease their treatment, or were liked or disliked by the crew. At some point, the entire ceremony devolved into a water battle and those whose baptism included having their faces blackened proceeded to rub themselves on those whose hadn’t until everyone was dirty and soaked in sea water. The rest of the day was “passed in dancing, and other kind of amusements.”

This raises the question “what if you didn’t WANT to participate?” Let’s admit it, in the 17th and 18th centuries the ceremony could be quite brutal–especially after the English incorporated getting a close shave into the event. Just imagine having your face lathered with a mixture of grease, tar, fish guts, poop (!) and anything else at hand only to have it scraped off with a piece of rusty iron barrel hoop! Um, no thanks. Or how about getting reverse mohawk?

Crews must have run into this issue fairly early on because even in the earliest days of the ceremony there were ways to get out of it—or at least ways of reducing the severity of the experience. In 1557 De Léry was able to exempt himself from the activity by making a payment of wine and in 1642 Thomas Holm stated that paying the sailors a little money would limit the experience to “only a little sprinkling.” As the centuries progressed, payments of money or alcohol were slowly phased out as captains tried to prevent their crews from extorting more and more from the ship’s passengers; not to mention trying to reduce the amount of time the crew spent drunk from all of the alcohol they’d received from those who opted out!

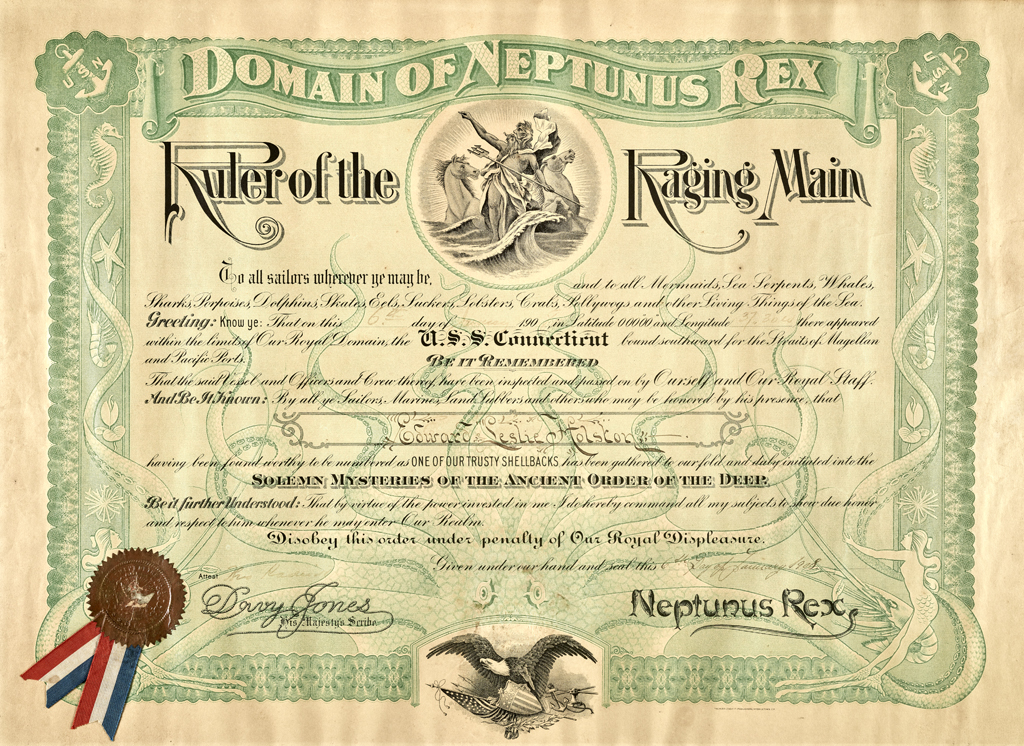

If you did get baptized at least you didn’t have to do it again. But what sort of proof could you offer that you were a “shellback” (the modern word applied to those who’ve been initiated)? D’Abbeville’s 1612 account states that initiates “received a word for safeguarding in the future.” While giving a “password” may have been a concept limited to D’Abbeville’s ship, it was almost certainly intended to be a signal to others of one’s position among the ranks of the initiated. In 1666 Alexander-Olivier Exquemelin states that the crew were required to place their hand upon a sea chart showing the equator and swear whether or not they had crossed the line before. This must have been pretty serious because it was apparently a good way of identifying those who “needed” to be baptized. If doubt was raised about a sailor’s veracity, he was made to eat bread and salt as a way of affirming his oath.

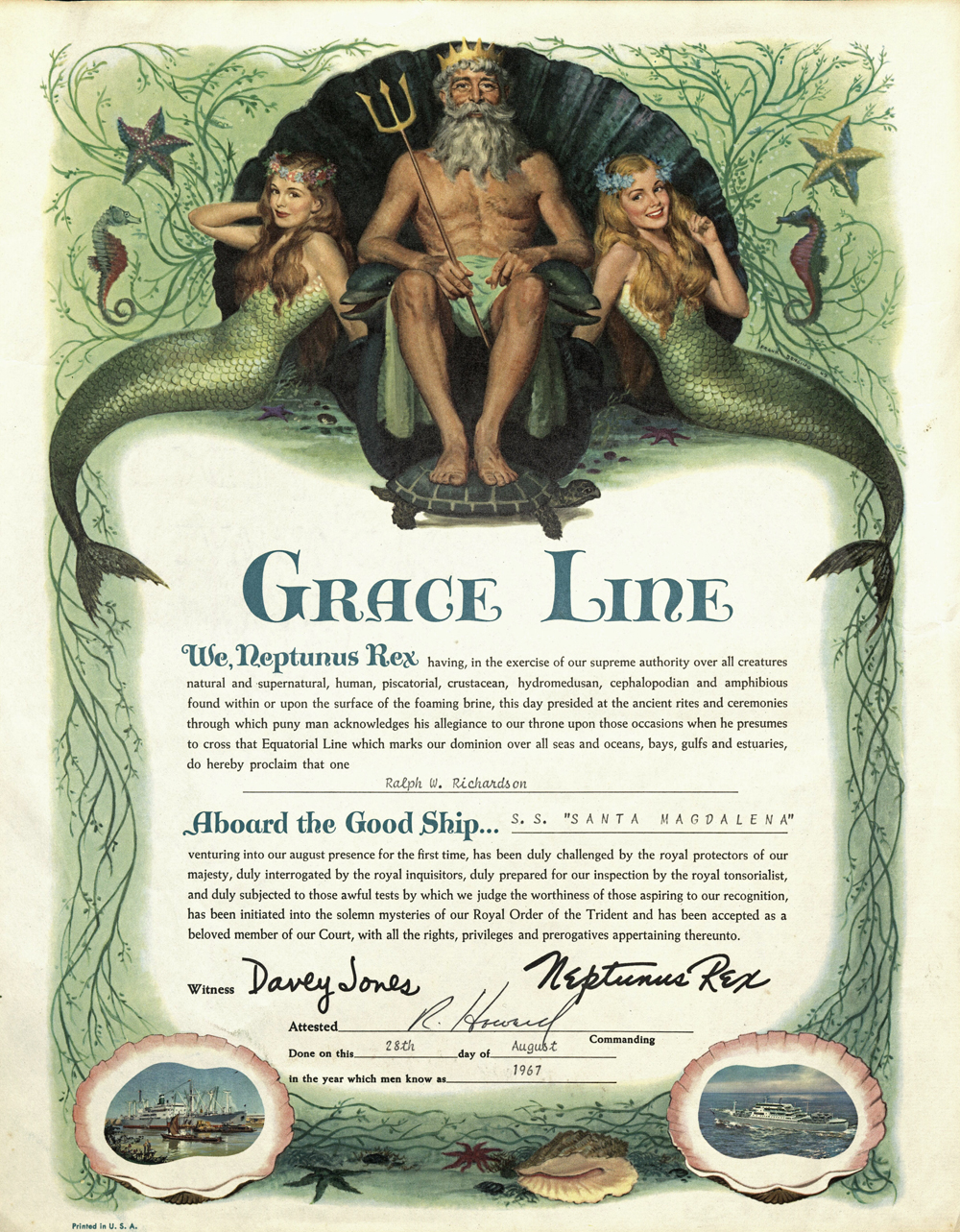

In 1730, the passengers on a Spanish ship bound for Vera Cruz apparently requested a “passport” excusing them from future baptisms (I’m not sure whether they received one or not!) and an 1824 account mentions the initiates receiving a “free pass” that was valid for life. It wasn’t until 1867 that the crew of the Danish frigate Iphigénie issued a certificate signed by Neptune documenting each passenger’s baptism. Interestingly, these certificates have become so highly prized it has actually started another interesting phenomena—initiates who actually want to be baptized purely as a way of getting their name on one of these certificates (granted, baptisms aboard cruise ships in the 21st century aren’t quite as grueling as they were in the 17th century!).

Since the late 19th century, the number and range of vessels ritually observing the crossing of the equator has expanded exponentially. Rituals are carried out on personal sailboats, large passenger ships, naval warships and all forms of commercial vessels. In fact, the tradition may be more widely observed today than in any previous century.

Almost makes me want to book a cruise and take a trip across the equator!